Philip M. Hanno, MD, MPH

Bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis (BPS/IC) is a condition diagnosed on a clinical basis and requiring a high index of suspicion on the part of the clinician. Simply put, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of the patient presenting with chronic pelvic pain that is often exacerbated by bladder filling and associated with urinary frequency. One can argue that it is a symptom-complex because it has a differential diagnosis that should be explored in a timely fashion before or at the time of initiation of empirical therapy (Blaivas, 2007). Once other conditions have been ruled out it can be considered a syndrome that generally responds to one of a variety of therapeutic approaches in the majority of cases. The perception that the original term interstitial cystitis was not at all descriptive of the clinical syndrome or even the pathologic findings in many cases has led to the current effort to reconsider the name of the disorder and even the way it is positioned in the medical spectrum (Hanno, 2008). What was originally considered a bladder disease is now considered a chronic pain syndrome (Janicki, 2003) that may begin as a pathologic process in the bladder in most but not all patients and eventually can develop into a disease that in a small subset of those affected even cystectomy may not benefit (Baskin and Tanagho, 1992). Its relationship to type III chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS)/nonbacterial prostatitis is unclear (Chai, 2002; Hakenberg and Wirth, 2002). Its association with other chronic pain syndromes has taken on more importance recently as a promising clue to unlock the challenging etiologic and therapeutic puzzle of this condition.

BPS/IC encompasses a major portion of the “painful bladder” disease complex. “Painful bladder disorders” comprise a large group of patients with bladder and/or urethral and/or pelvic pain, irritative voiding symptoms (urgency, frequency, nocturia, dysuria), and sterile urine cultures. Painful bladder conditions with well-established causes include radiation cystitis, cystitis caused by microorganisms that are not detected by routine culture methodologies, and systemic disorders that affect the bladder. In addition, many gynecologic disorders can mimic BPS/IC (Kohli et al, 1997; Howard, 2003a, 2003b). BPS/IC has no easily discernible etiology.

The symptoms are allodynic, an exaggeration of normal sensations. There are no pathognomonic findings on pathologic examination, and even the finding of petechial hemorrhages on the bladder mucosa during cystoscopy after bladder hydrodistention under anesthesia is no longer considered the sine qua non of BPS/IC that it had been until a decade ago ( Erickson, 1995; Waxman et al, 1998; Erickson et al, 2005). BPS/IC is truly a diagnosis of exclusion. It may have multiple causes and represent a final common reaction of the bladder to different types of insult.

Definition

“It resembles a constellation of stars; its components are real enough but the pattern is in the eye of the beholder” (Makela and Heliovaara, 1991). This evocative description of fibromyalgia could equally apply to BPS/IC. Indeed, it has been argued, not necessarily convincingly, that each medical specialty has at least one somatic syndrome (irritable bowel syndrome, chronic pelvic pain, fibromyalgia, tension headache, noncardiac chest pain, hyperventilation syndrome) that might be better conceptualized as a part of a general functional somatic syndrome than with the symptom-based classification that we have now that may be more a reflection of professional specialization and access to care (Wessely and White, 2004).

BPS/IC is a clinical diagnosis based primarily on chronic symptoms of pain perceived by the patient to emanate from the bladder and/or pelvis associated with urinary urgency/frequency in the absence of other identified causes for the symptoms. It has been defined and redefined over the past century, and as the problem of definition has become more prominent lately so have the number of definitions and attempts to crystallize just what the diagnosis means (Table 12–1). The International Continence Society (ICS) prefers the term painful bladder syndrome (PBS), defined as “the complaint of suprapubic pain related to bladder filling, accompanied by other symptoms such as increased daytime and night-time frequency, in the absence of proven urinary infection or other obvious pathology” (Abrams et al, 2002). The ICS reserves the diagnosis of IC to patients with “typical cystoscopic and histological features,” without further specifying these. This definition may miss 36% of patients, primarily because it confines the pain to a suprapubic location and mandates a relationship of pain to bladder filling (Warren et al, 2006).

Table 12–1 Definitions of Bladder Pain Syndrome/Painful Bladder Syndrome/Interstitial Cystitis Syndrome over the Past Century

| YEAR | DEFINITION | SOURCE |

|---|---|---|

| 1887 | Skene: An inflammation that has destroyed the mucous membrane partly or wholly and extended to the muscular parietes | Skene, 1887 |

| 1915 | Hunner: A peculiar form of bladder ulceration whose diagnosis depends ultimately on its resistance to all ordinary forms of treatment in patients with frequency and bladder symptoms (spasms) | Hunner, 1915 |

| 1951 | Bourque: Patients who suffer chronically from their bladder; and we mean the ones who are distressed, not only periodically but constantly, having to urinate at all hours of the day and of the night suffering pains every time they void. | Bourque, 1951 |

| 1978 | Messing and Stamey: Nonspecific and highly subjective symptoms of around-the-clock frequency, urgency, and pain somewhat relieved by voiding when associated with glomerulations upon bladder distention under anesthesia. | Messing and Stamey, 1978 |

| 1990 | Revised NIDDK criteria: Pain associated with the bladder or urinary urgency, and glomerulations or Hunner ulcer on cystoscopy under anesthesia, in patients with 9 months or more of symptoms—at least 8 voids per day, 1 void per night, and cystometric bladder capacity less than 350 mL | Wein et al, 1990 |

| 1997 | NIDDK Interstitial Cystitis Database entry criteria: Unexplained urgency or frequency (7 or more voids per day) or pelvic pain of at least 6 months’ duration in the absence of other definable causes. | Simon et al, 1997 |

| 2008 | European Society for the Study of Interstitial Cystitis: Chronic (>6 months) pelvic pain, pressure, or discomfort perceived to be related to the urinary bladder accompanied by at least one other urinary symptom such as persistent urge to void or frequency. Confusable diseases as the cause of the symptoms must be excluded. | Van de Merwe et al, 2008 |

| 2009 | Japanese Urological Association: A disease of the urinary bladder diagnosed by three conditions: (1) lower urinary tract symptoms such as urinary frequency, bladder hypersensitivity and/or bladder pain; (2) bladder pathology proven endoscopically by Hunner ulcer and/or mucosal bleeding after overdistention; and (3) exclusion of confusable diseases such as infection, malignancy, or calculi of the urinary tract. | Homma et al, 2009 |

| 2009 | Society for Urodynamics and Female Urology informal international dialogue consensus meeting: An unpleasant sensation (pain, pressure, discomfort) perceived to be related to the urinary bladder, associated with lower urinary tract symptoms of more than 6 weeks’ duration, in the absence of infection or other identifiable causes. | Hanno and Dmochowski, 2009 |

Data from Hanno PM, Lin AT, Nordling J, et al. Bladder pain syndrome. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A, editors. Incontinence. Paris: Health Publication Ltd.; 2009. p. 1459–518.

In the absence of clear criteria for IC, this chapter will refer to BPS/IC and IC interchangeably, because all but recent literature terms the syndrome IC. The definition of the European Society for the Study of Interstitial Cystitis (ESSIC) is a clinically useful one, and changes made since its original iteration have likely made it more sensitive and inclusive (Mouracade et al, 2008). Minor modifications made at a meeting under the auspices of the Society for Urodynamics and Female Urology (SUFU) may be preferred by some clinicians. Perhaps more than for most diseases, how we arrived at this point is instructive and critical to an overall understanding of BPS/IC. The paradigm change that has resulted in morphing what was originally considered a bladder disease (aptly named interstitial cystitis) to a chronic pain syndrome (bladder pain syndrome) also merits discussion.

Historical Perspective

Recent historical reviews confirm that IC was recognized as a pathologic entity during the 19th century (Christmas, 1997; Parsons and Parsons, 2004). Joseph Parrish, a Philadelphia surgeon, described three cases of severe lower urinary tract symptoms in the absence of a bladder stone in an 1836 text (Parrish, 1836) and termed the disorder tic doloureux of the bladder. Teichman and associates (2000) argue that this may represent the first description of IC. Fifty years later Skene (1887) used the term interstitial cystitis to describe an inflammation that has “destroyed the mucous membrane partly or wholly and extended to the muscular parietes.”

Early in the 20th century, at a New England Section meeting of the American Urological Association, Guy Hunner (1915, 1918) reported on eight women with a history of suprapubic pain, frequency, nocturia, and urgency lasting an average of 17 years. He drew attention to the disease, and the red, bleeding areas he described on the bladder wall came to have the pseudonym of Hunner ulcer. As Anthony Walsh (1978) observed, this has proven to be unfortunate. In the early part of the 20th century the very best cystoscopes available gave a poorly defined and ill-lit view of the fundus of the bladder. It is not surprising that when Hunner saw red and bleeding areas high on the bladder wall he thought they were ulcers. For the next 60 years urologists would look for ulcers and fail to make the diagnosis in their absence. The disease was thought to be focal rather than a pancystitis.

Hand (1949) authored the first comprehensive review about the disease, reporting 223 cases. In looking back, his paper was truly a seminal one, years ahead of its time. Many of his epidemiologic findings have held up to this day. His description of the clinical findings bears repeating. “I have frequently observed that what appeared to be a normal mucosa before and during the first bladder distention showed typical interstitial cystitis on subsequent distention.” He notes, “small, discrete, submucosal hemorrhages, showing variations in form … dot-like bleeding points … little or no restriction to bladder capacity.” He portrays three grades of disease, with grade 3 matching the small-capacity, scarred bladder described by Hunner. Sixty-nine percent of patients had grade 1 disease, and only 13% had grade 3 disease.

Walsh (1978) later coined the term glomerulations to describe the petechial hemorrhages that Hand had described. But it was not until Messing and Stamey (1978) discussed the “early diagnosis” of IC that attention turned from looking for an ulcer to make the diagnosis to the concepts that (1) symptoms and glomerulations at the time of bladder distention under anesthesia were the disease hallmarks and (2) the diagnosis was primarily one of exclusion.

Bourque’s Aunt Minnie (she is hard to define, but you know her when you see her) description of IC is over 50 years old and is worth recalling: “We have all met, at one time or another, patients who suffer chronically from their bladder; and we mean the ones who are distressed, not only periodically but constantly, having to urinate often, at all moments of the day and of the night, and suffering pains every time they void. We all know how these miserable patients are unhappy, and how those distressing bladder symptoms get finally to influence their general state of health physically at first, and mentally after a while” (Bourque, 1951).

Although memorable and right on the mark, this description and others like it were not suitable for defining this disease in a manner that would help physicians make the diagnosis and design research studies to learn more about the problem. Physician interest and government participation in research were sparked through the efforts of a group of frustrated patients led by Dr. Vicki Ratner, an orthopedic surgery resident in New York City, who founded the first patient advocacy group, the Interstitial Cystitis Association, in the living room of her small New York City apartment in 1984 (Ratner et al, 1992; Ratner and Slade, 1997). The first step was to develop a working definition of the disease. The modern history of PBS/IC is best viewed through the development of the modern definition.

Evolution of Definition

There are data to suggest that true urinary frequency in women can be defined as regularly having to void at intervals of less than 3 hours and 25% of women older than age 40 years have nocturia at least once (Glenning, 1985; Fitzgerald and Brubaker, 2003). Whereas bladder capacity tends to fall in women by the eighth and ninth decades of life, bladder volume at first desire to void tends to rise as women age (Collas and Malone-Lee, 1996). Based on a 90th percentile cut-off to determine the ranges of normality, the highest “normal” frequency ranges in the 4th decade range from 6 for men to 9 for women (Burgio et al, 1991). Large variation in the degree of bother with varying rates of frequency (Fitzgerald et al, 2002) makes a symptomatic diagnosis of PBS/IC based on an absolute number of voids subject to question, and frequency per volume of intake or even the concept of “perception of frequency” as a problem may be more accurate than an absolute number.

In an effort to define IC so that patients in different geographic areas, under the care of different physicians, could be compared, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) held a workshop in 1987 at which consensus criteria were established for the diagnosis of IC (Gillenwater and Wein, 1988). These criteria were not meant to define the disease but rather to ensure that groups of patients included in basic and clinical research studies would be relatively comparable. After pilot studies testing the criteria were performed, the criteria were revised at another NIDDK workshop a year later (Wein et al, 1990). These criteria are presented in Table 12–2.

Table 12–2 National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Diagnostic Criteria for Interstitial Cystitis

| To be diagnosed with interstitial cystitis, patients must have either glomerulations on cystoscopic examination or a classic Hunner ulcer, and they must have either pain associated with the bladder or urinary urgency. An examination for glomerulations should be undertaken after distention of the bladder under anesthesia to 80 to 100 cm H2O for 1 to 2 minutes. The bladder may be distended up to two times before evaluation. The glomerulations must be diffuse—present in at least three quadrants of the bladder—and there must be at least 10 glomerulations per quadrant. The glomerulations must not be along the path of the cystoscope (to eliminate artifact from contact instrumentation). The presence of any one of the following excludes a diagnosis of interstitial cystitis: |

• Bladder capacity of greater than 350 mL on awake cystometry using either a gas or liquid filling medium |

From Wein AJ, Hanno PM, Gillenwater JY. Interstitial cystitis: an introduction to the problem. In: Hanno PM, Staskin DR, Krane RJ, Wein AJ, editors. Interstitial cystitis. London: Springer-Verlag; 1990. p. 13–5.

Although meant initially to serve only as a research tool, the NIDDK “research definition” became a de facto definition of this disease, diagnosed by exclusion and colorfully termed a “hole in the air” by Hald (cited in George, 1986). Certain of the exclusion criteria serve mainly to make one wary of a diagnosis of IC but should by no means be used for categorical exclusion of such a diagnosis. However, because of the ambiguity involved, these patients should probably be eliminated from research studies or categorized separately. In particular, exclusion criteria 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 17, and 18 are only relative. What percentage of patients with idiopathic sensory urgency has IC is unclear (Frazer et al, 1990). The specificity of the finding of bladder glomerulations has come into question (Erickson, 1995; Waxman et al, 1998; Tomaszewski et al, 2001). Similarly, the sensitivity of glomerulations is also unknown, but clearly patients with IC symptoms can demonstrate an absence of glomerulations under anesthesia (Awad et al, 1992; Al Hadithi et al, 2002). Bladder ulceration is extremely rare and exists in less than 5% of patients in my experience and in the experience of others (Sant, 1991). A California series found 20% of patients to have ulceration (Koziol, 1994). Specific pathologic findings represent a glaring omission from the criteria, because there is a lack of consensus as to which pathologic findings, if any, are required for, or even suggestive of, a tissue diagnosis (Hanno et al, 1990, 2005a; Tomaszewski et al, 1999, 2001).

The unexpected use of the NIDDK research criteria by the medical community as a definition of IC led to concerns that many patients suffering from this syndrome might be misdiagnosed. The multicenter Interstitial Cystitis Database (ICDB) study through NIDDK accumulated data on 424 patients with IC, enrolling patients from May 1993 through December 1995. Entry criteria were much more symptom driven than those promulgated for research studies (Simon et al, 1997) and are noted in Table 12–3. In an analysis of the defining criteria (Hanno et al, 1999a, 1999b), it appeared the NIDDK research criteria fulfilled their mission. Fully 90% of expert clinicians agreed that patients diagnosed with IC by those criteria in the ICDB indeed had the disorder. However, 60% of patients deemed to have IC by these experienced clinicians would not have met NIDDK research criteria. Thus, IC remains a clinical syndrome defined by some combination of chronic symptoms of urgency, frequency, and/or pain in the absence of other reasonable causation. Whereas IC symptom and problem indices have been developed and validated (O’Leary et al, 1997; Goin et al, 1998), these are not intended to diagnose or define IC but rather to measure the severity of symptomatology and monitor disease progression or regression (Moldwin and Kushner, 2004).

Table 12–3 Interstitial Cystitis Database (ICDB) Study Eligibility Criteria

5. Urinating at least 7 times per day or having some urgency or pain (measured on linear analog scales) |

From Simon LJ, Landis JR, Erickson DR, Nyberg LM. The Interstitial Cystitis Data Base Study: concepts and preliminary baseline descriptive statistics. Urology 1997;49:64–75.

Nomenclature and Taxonomy

The literature over the past 170 years has seen numerous changes in description and nomenclature of the disease. The syndrome has variously been referred to as tic douloureux of the bladder, IC, cystitis parenchymatosa, Hunner ulcer, panmural ulcerative cystitis, urethral syndrome, and painful bladder syndrome (Skene, 1887; Hunner, 1918; Powell and Powell, 1949; Bourque, 1951; Christmas, 1997; Teichman et al, 2000; Dell and Parsons, 2004). The term interstitial cystitis, which Skene is credited with coining and Hunner brought in to common usage, is a misnomer; in many cases not only is there no interstitial inflammation, but also, histopathologically, there may be no inflammation at all (Lynes et al, 1990a; Denson et al, 2000; Tomaszewski et al, 2001; Rosamilia et al, 2003). By literally focusing exclusively on the urinary bladder, the term interstitial cystitis furthermore does not do justice to the condition from both the physician’s and the patient’s perspective. The textual exclusiveness ignores the high comorbidity with various pelvic, extrapelvic, and nonurologic symptoms and associated disorders (Clauw et al, 1997) that frequently precede or develop after the onset of the bladder condition (Wu et al, 2006).

With the formal definition of the term painful bladder syndrome by the ICS in 2002, the terminology discussion became an intense international focal point (Abrams et al, 2002):

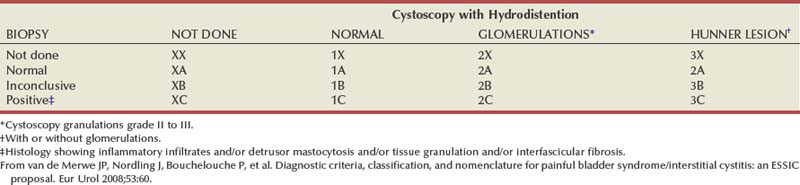

At the major biannual IC research conference in the fall of 2006, held by the NIDDK (Frontiers in Painful Bladder Syndrome/Interstitial Cystitis), the ESSIC group was given a block of time with which to present their thoughts and conclusions. Because (1) the term PBS did not fit into the taxonomy of other pelvic pain syndromes such as urethral or vulvar pain syndromes, (2) as defined by the International Continence Society missed over a third of afflicted patients, and (3) is a term open to different interpretations, the ESSIC suggested that painful bladder syndrome be redesignated as bladder pain syndrome (BPS), followed by a type designation. BPS is indicated by two symbols, the first of which corresponds to cystoscopy with hydrodistention findings (1, 2, or 3 indicating increasing grade of severity) and the second to biopsy findings (A, B, and C indicating increasing grade of pathologic severity) (Table 12–4). Although neither cystoscopy with hydrodistention nor bladder biopsy was prescribed as an essential part of the evaluation, by categorizing patients as to whether either procedure was done and, if so, the results, it is possible to follow patients with similar findings and study each identified cohort to compare natural history, prognosis, and response to therapy (van de Merwe et al, 2008).

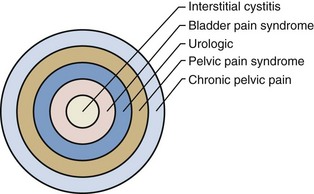

As Baranowski and associates (2008) conceived it, BPS is defined as a pain syndrome with a collection of symptoms, the most important of which is pain perceived to be in the bladder. IC is distinguished as an end-organ, visceral-neural pain syndrome, whereas BPS can be considered a pain syndrome that involves the end-organ (bladder) and neurovisceral (myopathic) mechanisms. In IC, one expects an end-organ primary pathologic process. This is not necessarily the case in the broader BPS.

A didactically very demonstrative way to conceptualize the dawning shift in conception of the condition is with the drawing of a target (Fig. 12–1). There may be many causes of chronic pelvic pain. When an etiology cannot be determined, it is characterized as pelvic pain syndrome. To the extent that it can be distinguished as urologic, gynecologic, dermatologic, and the like, it is further categorized by organ system. A urologic pain syndrome can sometimes be further differentiated on the site of perceived pain. Bladder, prostate, testicular, and epididymal pain syndromes follow. Finally, types of BPS can be further defined as IC or simply categorized by ESSIC criteria. Patient groups have expressed their concerns with regard to any nomenclature change that potentially drops the term interstitial cystitis because the U.S. Social Security Administration and private insurances recognize IC but not the term BPS and benefits potentially could be adversely affected. Whether the term interstitial cystitis, as difficult as it is to define and as potentially misleading as it is with regard to etiology and end-organ involvement, should be maintained is a subject of ongoing controversy (Hanno and Dmochowski, 2009).

Figure 12–1 Conceptualization of pelvic pain syndrome classification.

(From Hanno P. Interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome/bladder pain syndrome: the evolution of a new paradigm. In: Proceedings of the International Consultation on Interstitial Cystitis. Japan: Comfortable Urology Network; 2008. p. 2–9.)

Key Points

Definition

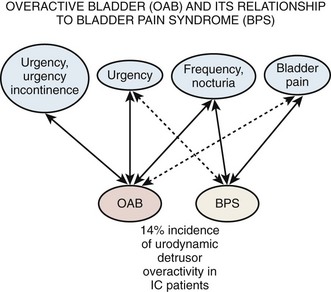

Urgency is a common complaint of this group of patients. The ICS definition of urgency (Abrams et al, 2002), “the complaint of a sudden compelling desire to pass urine, which is difficult to defer,” could be interpreted as compatible with either detrusor overactivity or BPS/IC depending on the weight one attaches to the word sudden. There are those who see hypersensitivity or sensory urgency as bridging both overactive bladder and BPS/IC (Haylen et al, 2007; Yamaguchi et al, 2007), and the issue has been nicely addressed by Homma (2008). Pain and pressure are more involved in the frequency of BPS/IC, and fear of incontinence seems the reason for the urgency of overactive bladder (Abrams et al, 2005). Thus, urgency is not required to define BPS/IC, because it would tend to obfuscate the borders of overactive bladder and PBS/IC and is unnecessary for definition purposes. Figure 12–2 (Abrams et al, 2005) is a graphic depiction of one view of the relationship between these two, sometimes confused, conditions. The 14% incidence of urodynamic detrusor overactivity in the PBS/IC patients (Nigro et al, 1997) is probably close to what one might expect in the general population if studied urodynamically (Salavatore et al, 2003).

Figure 12–2 Overactive bladder (OAB) and its relationship to bladder pain syndrome (BPS). IC, interstitial cystitis.

(From Abrams PH, Hanno PM, Wein AJ. Overactive bladder and painful bladder syndrome: there need not be confusion. Neurourol Urodyn 2005;24:149–50.)

Still, there remains some ambiguity, and further research is necessary with regard to urgency. Studies are hampered by the fact that patients tend to use words to describe lower urinary tract symptoms but attribute meanings to the words different from physicians and researchers (Digesu et al, 2008). An analysis of urgency by the University of Maryland group reported that 65% of patients with BPS experienced an urge to urinate to relieve pain, with 46% agreeing that they had an urge to relieve pain and not to prevent incontinence. Still, 21% reported that urgency was for fear of impending incontinence and that this sensation was not present before the onset of BPS symptoms (Diggs et al, 2007). In some patients the term connotes an intensification of the normal urge to void, and in others it is a different sensation (Blaivas et al, 2009).

New efforts to phenotype the chronic urologic pain syndromes (BPS and chronic nonbacterial prostatitis/CPPS in men) are being explored (Nyberg et al, 2009; Shoskes et al, 2009a, 2009b). The hope is that looking at psychological, physical, and organ-specific parameters of afflicted patients, and specifically focusing on associated disorders, will aid in proper selection of therapeutic agents that may have selective specificity for different symptom constellations and also may improve productivity and results of research on etiology, prognosis, and new therapeutic agents.

Epidemiology

Prevalence

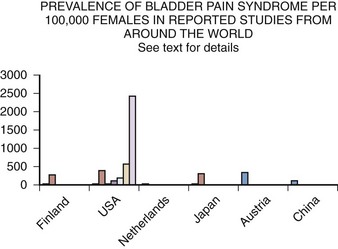

Epidemiology studies of PBS/IC are hampered by many problems (Bernardini et al, 1999). The lack of an accepted definition, the absence of a validated diagnostic marker, and questions regarding etiology and pathophysiology make much of the literature difficult to interpret. This is most apparent when one looks at the variation in prevalence reports in the United States and around the world (Table 12–5). These range from 1.2 per 100,000 population and 4.5 per 100,000 females in Japan (Ito et al, 2000), to a questionnaire-based study that suggests a figure in American women of 20,000 per 100,000 (Parsons and Tatsis, 2004)!

Table 12–5 Prevalence of BPS/IC per 100,000 Women

| STUDY | PREVALENCE |

|---|---|

| Oravisto, 1975 (Finland) | 18 |

| Jones, 1989 (USA) | 500 |

| Held et al, 1990 (USA) | 30 |

| Bade et al, 1995 (Netherlands) | 12 |

| Curhan et al, 1999 (USA) | 60 |

| Ito et al, 2000 (Japan) | 4.5 |

| Roberts et al, 2003 (USA) | 1.6 |

| Leppilahti et al, 2005 (Finland) | 300 |

| Clemens, 2007b (USA) | 197 |

| Temml et al, 2007 (Austria) | 306 |

| Song et al, 2009 (China) | 100 |

| Berry et al, 2009 (USA) | 2600 |

It has been estimated that the prevalence of chronic pain due to benign causes in the population is at least 10% (Verhaak et al, 1998). Numerous case series have, until recently, formed the basis of epidemiologic information regarding PBS/IC. Farkas and associates (1977) discussed IC in adolescent girls. Hanash and Pool (1969) reviewed their experience with IC in men. Geist and Antolak (1970) reviewed and added to reports of disease occurring in childhood. A childhood presentation is extremely rare and must be differentiated from the much more common and benign-behaving extraordinary urinary frequency syndrome of childhood, a self-limited condition of unknown etiology (Koff and Byard, 1988; Robson and Leung, 1993). Nevertheless there is a small cohort of children with chronic symptoms of bladder pain, urinary frequency, and sensory urgency in the absence of infection who have been evaluated with urodynamics, cystoscopy, and bladder distention and have findings consistent with the diagnosis of PBS/IC. In Close and colleagues’ review of 20 such children (1996) the median age at onset was younger than 5 years and the vast majority of patients had long-term remissions with bladder distention.

A study conducted at the Scripps Research Institute (Koziol et al, 1993) included 374 patients at Scripps as well as some members of the Interstitial Cystitis Association, the large patient support organization. A more recent, but similar study in England (Tincello and Walker, 2005) concurred with the Scripps findings of urgency, frequency, and pain in the vast majority of these patients, devastating effects on quality of life, and often unsuccessful attempts at therapy with a variety of treatments. Although such reviews provide some information, they would seem to be necessarily biased by virtue of their design.

Several population-based studies have been reported in the literature (Fig. 12–3), and these studies tend to support the reviews of selected patients or from individual clinics and the comprehensive follow-up case-control study by Koziol (1994). The first population-based study (Oravisto, 1975) included “almost all the patients with interstitial cystitis in the city of Helsinki.” This superb, brief report from Finland surveyed all diagnosed cases in a population approaching 1 million. The prevalence of the disease in women was 18.1 per 100,000. The joint prevalence in both sexes was 10.6 cases per 100,000. The annual incidence of new female cases was 1.2 per 100,000. Severe cases accounted for about 10% of the total. Ten percent of cases were in men. The disease onset was generally subacute rather than insidious, and full development of the classic symptom-complex occurred over a relatively short time. IC does not progress continuously but usually reaches its final stage rapidly (within 5 years) in the Koziol study (1993) and then continues without significant change in symptomatology. Subsequent major deterioration was found by Oravisto to be unusual. The duration of symptoms before diagnosis was 3 to 5 years in the Finnish study. Analogous figures in a classic American paper a quarter of a century earlier were 7 to 12 years (Hand, 1949).

Another early population study, this one in the United States, first demonstrated the potential extent of what had been considered a very rare disease (Held et al, 1990). The following population groups were surveyed: (1) random survey of 127 board-certified urologists, (2) 64 IC patients selected by the surveyed urologists and divided between the last patient with IC seen and the last patient with IC diagnosed, (3) 904 female patients belonging to the Interstitial Cystitis Association, and (4) random phone survey of 119 persons from the U.S. population. This 1987 study reached the following conclusions:

Other population studies followed. Jones and Nyberg (1997) obtained their data from self-report of a previous diagnosis of IC in the 1989 National Household Interview Survey. The survey estimated that 0.5% of the population, or more than 1 million people in the United States, reported having a diagnosis of IC. There was no verification of this self-report by medical records. Bade and colleagues (1995) did a physician questionnaire-based survey in the Netherlands yielding an overall prevalence of 8 to 16/100,000 females, with diagnosis heavily dependent on pathology and presence of mast cells. This prevalence in females compares to 4.5/100,000 in Japan (Ito et al, 2000).

The Nurses Health Study I and II (Curhan et al, 1999) showed a prevalence of IC between 52 and 67/100,000 in the United States, which was twice the prevalence in the study by Held and associates (1990) and threefold greater than the study by Bade and colleagues (1995) in The Netherlands. It improved on previous studies by using a large sample derived from a general population and careful ascertainment of the diagnosis. If the 6.4% confirmation rate of their study were applied to the Jones and colleagues’ National Health Interview Survey data, the prevalence estimates of the two studies would be nearly identical.

Leppilahti and coworkers (2002, 2005) used the O’Leary-Sant IC symptom and problem index (never validated for making a diagnosis per se) to select women with IC symptoms from the Finnish population register. Of 1331 respondents, 32 had moderate or severe symptoms involving a suspicion of BPS/IC (symptom score 7 or higher). Of 21 who consented to clinical evaluation, 7 had probable or possible BPS/IC. Corrected estimates yielded a prevalence of 300/100,000 women. Similar studies without clinical confirmation suggested prevalence in Austrian women of 306/100,000 (Temml et al, 2007) and in Japanese women of 265/100,000 (Inoue et al, 2009). Using the Bristol Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms questionnaire, a 100/100,000 prevalence of BPS symptoms was reported in Fuzhou Chinese women (Song et al, 2009).

Roberts and coworkers (2003), using a physician diagnosis as the arbiter of IC, found annual incidence in Olmsted County, Minnesota, of 1.6 per 100,000 in women and 0.6 per 100,000 in men, a figure remarkably similar to that of Oravisto in Helsinki. The cumulative prevalence by age older than 80 years in the Minnesota study was 114 per 100,000, a figure comparable to that in the Nurses Health Study if one takes into account the younger age group in the Curhan data. Clemens and colleagues (2007b) calculated a prevalence of diagnosed disease in a managed care population of 197 per 100,000 women and 41 per 100,000 men, but when the diagnosis was tested by eliminating those who had not been evaluated with endoscopy or in whom exclusionary conditions existed, the numbers dropped considerably. The Boston Area Community Health Survey estimated a prevalence of painful bladder syndrome symptoms of 1% to 2% of the population depending on the definition used.

Looking at office visits to practices with an interest in urologic problems, 2.8% of patients in Canadian urologist offices had BPS/IC (Nickel et al, 2005) and probable BPS/IC was found in 0.57% in a primary care office in Michigan (Rosenberg and Hazzard, 2005).

An estimation of the prevalence at this time, recognizing that a consistent definition of the condition has not been used in epidemiologic studies, appears to be about 300/100,000 females and a male prevalence of 10% to 20% of the female estimate. A National Institutes of Health (NIH)-sponsored 5-year Rand Corporation epidemiology study is due to be completed in 2010 and may yield the most reliable data yet (Bogart et al, 2007). Preliminary results reported at the annual American Urological Association meeting revealed that 2.5% to 2.7% of the population of U.S. women meet a high specificity symptom definition suggesting BPS/IC. With the use of an epidemiologic definition with higher sensitivity, the prevalence was 6.5%. This translates to a prevalence in women older than 18 years of age in the United States who have symptoms by self-report compatible with BPS/IC of 3.4 to 7.9 million, significantly higher than most previous prevalence estimates (Berry et al, 2009).

Whether the considerable variability in prevalence in studies within the United States and around the world is related to methodology or true differences in incidence is an important question yet to be answered. It is clear that the prevalence of BPS/IC symptoms is much greater than the prevalence of a physician diagnosis of the disease (Clemens et al, 2007a). Familial occurrence of PBS/IC has been reported (Dimitrakov, 2001). A hereditary aspect to incidence has been suggested by Warren and associates (2001, 2004) in a pioneering study who found that adult female first-degree relatives of patients with IC may have a prevalence of IC 17 times that found in the general population. This, together with previously reported evidence showing a greater concordance of IC among monozygotic than dizygotic twins suggests, but does not prove, a genetic susceptibility to IC that could partially explain the discord in prevalence rates in different populations.

Characteristics and Natural History

Most studies show a female-to-male preponderance of 5 : 1 or greater (Clemens et al, 2005; Hanno et al, 2005a). In the absence of a validated marker it is often difficult to distinguish PBS/IC from CPPS (nonbacterial prostatitis, prostatodynia) that affects males (Forrest and Schmidt, 2004), and the percentage of men with PBS/IC may actually be higher (Miller et al, 1995, 1997; Novicki et al, 1998). Men tend to be diagnosed at an older age and have a higher percentage of Hunner ulcer in the case series reported (Novicki et al, 1998; Roberts et al, 2003). Costs of the disorder are not insignificant and can range from 4 to 7 thousand dollars a year not including lost wages, costs preceding diagnosis, alternative therapies, and costs attributable to misdiagnosis (Clemens et al, 2008c, 2009).

The Interstitial Cystitis Database Cohort (ICDB) of patients has been carefully studied, and the findings seem to bear out those of other epidemiologic surveys (Propert et al, 2000). Patterns of change in symptoms with time suggest regression to the mean and an intervention effect associated with the increased follow-up and care of cohort participants. Although all symptoms fluctuated there was no evidence of significant long-term change in overall disease severity. The data suggest that PBS/IC is a chronic disease, and no current treatments have a significant impact on symptoms over time in the majority of patients. Quality of life studies suggest that PBS/IC patients are six times more likely than individuals in the general population to cut down on work time owing to health problems but only half as likely to do so as patients with arthritis (Shea-O’Malley and Sant, 1999). There is an associated high incidence of comorbidity, including depression, chronic pain, and anxiety and overall mental health issues (Michael et al, 2000; Rothrock et al, 2002; Hanno et al, 2005a). There seems to be no effect on pregnancy outcomes (Onwude and Selo-Ojeme, 2003).

Female patients with BPS/IC seem to report significant dyspareunia and other manifestations of sexual dysfunction. All domains of female sexual function including sexually related distress, desire, and orgasm frequency can be affected (Ottem et al, 2007; Peters et al, 2007b). Sexual function is an important predictor of physical quality of life and was the only strong predictor of mental quality of life in one recent study of patients with severe BPS/IC (Nickel et al, 2007).

The Boston Area Community Health Survey (BACH) (Link et al, 2008) showed an overall prevalence of symptoms suggestive of BPS of 2% with twice as many women as men affected. It was most common among middle-aged respondents with an earlier peak in women. It also was most common among minorities and those of lower socioeconomic status, and socioeconomic status seemed to overcome any effect due to race or ethnicity. Emotional, sexual, and physical abuse was shown to be a risk factor in BACH (Link and Lutfey, 2007), and this has been borne out in other studies. A Michigan study compared a control group of 464 women with 215 BPS/IC patients and found 22% of the control group having experienced abuse versus 37% of the patient group (Peters and Kalinowski, 2007). Those with a history of sexual abuse may present with more pain and fewer voiding symptoms (Seth and Teichman, 2008). How reliable these data are is not clear, and it would be wrong to jump to any conclusions about abuse in an individual patient. However, practitioners need to have sensitivity for the possibility of an abusive relationship history in all pain patients and in BPS patients in particular. When patients are found to have multiple diagnoses, the rate of previous abuse also increases, and these patients may need referral for further counseling at a traumatic stress center (Fenton et al, 2008).

Key Points

Natural History

Associated Disorders

Knowledge of associated diseases is relevant for the clues it engenders with regard to etiology and possible treatment of this enigmatic pain syndrome. It is well known that patients with chronic pain syndromes including chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and temporomandibular disorder share key symptoms and can often develop overlapping conditions, including chronic pelvic pain (Aaron and Buchwald 2001; Aaron et al, 2001). In a case-control study Erickson found that patients with IC had higher scores than controls for pelvic discomfort, backache, dizziness, chest pain, aches in joints, abdominal cramps, nausea, palpitations, and headache (Erickson et al, 2001). Buffington theorizes that a common stress response pattern of increased sympathetic nervous system function in the absence of comparable activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis may account for some of these related symptoms (Buffington, 2004). It has been suggested that panic disorder, a diagnosis associated with some BPS/IC patients (Clemens et al, 2008a), may sometimes be a part of a familial syndrome that includes IC, thyroid disorders, and other disorders of possible autonomic or neuromuscular control (Weissman et al, 2004). Depression has been associated with BPS/IC in both men and women (Hall et al, 2008; Clemens et al, 2008a), but whether this is an association or effect of the disorder is uncertain (Fitzgerald et al, 2007).

Newly diagnosed patients are most concerned with the possibility that BPS/IC could be a forerunner of bladder carcinoma. No reports have ever documented a relationship to suggest that IC is a premalignant lesion. Utz and Zincke (1973) discovered bladder cancer in 12 of 53 men treated for IC at the Mayo Clinic. Three of 224 women were eventually diagnosed with bladder cancer. Four years later additional cases were reported (Lamm and Gittes, 1977). Tissot and coworkers (2004) reported 1% of 600 patients previously diagnosed as having IC were found to have transitional cell carcinoma as the cause of symptoms. Somewhat ominously, 2 of these patients had no hematuria. In all patients, irritative symptoms resolved after treatment of the malignancy. From this experience has come the dictum that all patients with presumed IC should undergo cystoscopy, urine cytology, and bladder biopsy of any suspicious lesion to be sure that a bladder carcinoma is not masquerading as BPS/IC. It would seem that in the absence of microhematuria, and with a negative cytology, the risk of missing a cancer is negligible but not zero. There is no evidence that BPS/IC itself is associated with a higher risk of bladder cancer or transitions to cancer over time (Murphy et al, 1982).

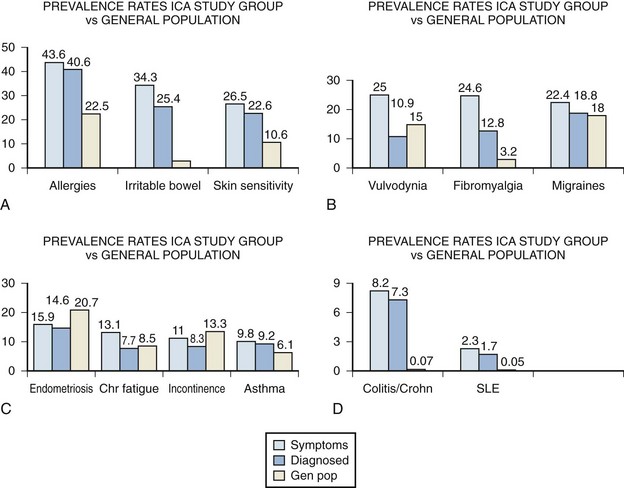

A large-scale survey of 6783 individuals diagnosed by their physicians as having IC studied the incidence of associated disease in this population (Alagiri et al, 1997). Data from the 2405 responders was validated by comparison with 277 nonresponders (Fig. 12–4). Allergies were the most common association, with over 40% affected. Allergy was also the primary association in Hand’s study (Hand, 1949). Thirty percent of patients had a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome, a finding confirming that of Koziol (1994). Altered visceral sensation has been implicated in irritable bowel syndrome in that these patients experience intestinal pain at intestinal gas volumes that are lower than those that cause pain in healthy persons (Lynn and Friedman, 1993), strikingly similar to the pain on bladder distention in IC.

(From Alagiri M, Chottiner S, Ratner V, et al. Interstitial cystitis: unexplained associates with other chronic pain syndromes. Urology 1997;49[Suppl 5A]:52–7.)

Fibromyalgia, another disorder frequently considered functional because no specific structural or biochemical cause has been found, is also overrepresented in the BPS/IC population. This is a painful, nonarticular condition predominantly involving muscles; it is the most common cause of chronic, widespread musculoskeletal pain. It is typically associated with persistent fatigue, nonrefreshing sleep, and generalized stiffness. As in BPS/IC, women are affected at least 10 times more often than men (Consensus document on fibromyalgia, 1993). The association is intriguing because both conditions have nearly identical demographic features, modulating factors, associated symptoms, and response to tricyclic antidepressants (Clauw et al, 1997).

Diagnosed vulvodynia, migraine headaches, endometriosis, chronic fatigue syndrome, incontinence, and asthma had similar prevalence as in the general population. Several publications have noted an association between BPS/IC and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (Fister, 1938; Boye et al, 1979; De la Serna and Alarçon-Segovia, 1981; Weisman et al, 1981; Meulders et al, 1992). The question has always been as to whether the bladder symptoms represent an association of these two disease processes or rather are a manifestation of lupus involvement of the bladder (Yukawa et al, 2008) or even a myelopathy with involvement of the sacral cord in a small group of these patients (Sakakibara et al, 2003). The beneficial response of the cystitis of systemic lupus erythematosus to corticosteroids (Meulders et al, 1992) tends to support the latter view. No association with discoid lupus has been demonstrated (Jokinen et al, 1972b). Although the actual numbers are small, the Alagiri study demonstrated a 30 to 50 times greater incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus in the IC group compared with the general population. Overall, the incidence of collagen vascular disease in the IC population is low. Parsons (1990) found only 2 of 225 consecutive IC patients to have a history of an autoimmune disorder.

Inflammatory bowel disease was found in over 7% of the IC population Alagiri studied, a figure 100 times higher than in the general population. Although unexplained at this time, abnormal leukocyte activity has been implicated in both conditions (Bhone et al, 1962; Kontras et al, 1971).

The University of Maryland group sought antecedent nonbladder syndromes in 313 patients with incident BPS/IC and compared them to 313 matched controls (Warren et al, 2009). They found 11 antecedent syndromes were more often diagnosed in those with BPS/IC, and most syndromes appeared in clusters. The most prominent cluster (45%) comprised fibromyalgia—chronic widespread pain, chronic fatigue syndrome, sicca syndrome, and/or irritable bowel syndrome. Most of the other syndromes and identified clusters were associated with it. They found probable chronic fatigue syndrome in 20% of BPS/IC patients, probable fibromyalgia in 22%, and probable irritable bowel in 27% of the BPS patients. Far fewer had physician reported diagnoses of these syndromes, and odds ratios (OR) for BPS/IC versus controls were 2.5 to 2.9. Study of a managed care database in Portland Oregon revealed that patients coded for gastritis (OR = 12.2), child abuse (OR = 9.3), fibromyalgia (OR = 3.0), anxiety disorder (OR = 2.8), headache (OR = 2.5), and depression (OR = 2.0) were commonly diagnosed with BPS/IC (Clemens et al, 2008b).

A mysterious disorder that has been associated with IC is focal vulvitis. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome is a constellation of symptoms and findings involving and limited to the vulvar vestibule consisting of (1) severe pain on vestibular touch to attempted vaginal entry, (2) tenderness to pressure localized within the vulvar vestibule, and (3) physical findings confined to vulvar erythema of various degrees (Marinoff and Turner, 1991). McCormack (1990) reported on 36 patients with focal vulvitis, 11 of whom also had IC. Fitzpatrick and coworkers (1993) has added three more cases. The concordance of these noninfectious inflammatory syndromes involving the tissues derived from the embryonic urogenital sinus and the similarity of the demographics argue for a common etiology.

An association has been reported between IC and Sjögren syndrome, an autoimmune exocrinopathy with a female preponderance manifested by dry eyes, dry mouth, and arthritis but that can also include fever, dryness, and gastrointestinal and lung problems. Van de Merwe and colleagues (1993) investigated 10 IC patients for the presence of Sjögren syndrome. Two patients had both the keratoconjunctivitis sicca and focal lymphocytic sialoadenitis allowing a primary diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome. Only 2 patients had neither finding. These researchers later (2003) reported an incidence of 28% of Sjögren syndrome in patients with IC. The incidence of symptoms of PBS/IC in patients with Sjögren syndrome has been estimated to be up to 5% (Leppilahti et al, 2003).

A negative correlation with diabetes has been noted (Parsons, 1990; Koziol, 1994; Warren et al, 2009).

Further epidemiologic studies are warranted because the epidemiology of this disorder may ultimately yield as many clues to etiology and treatment as other avenues of research. The heterogeneity of causes and symptoms of CPPS suggests that proper clinical phenotyping could foster the development of better treatments for individual phenotypes and more successful treatments for all afflicted patients (Baranowski et al, 2008; Shoskes et al, 2009b).

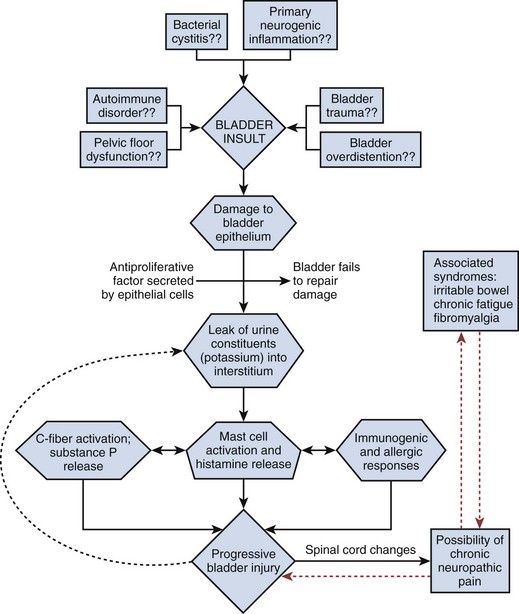

Etiology

It is likely that PBS/IC has a multifactorial etiology that may act predominantly through one or more pathways resulting in the typical symptom-complex (Holm-Bentzen et al, 1990; Mulholland and Byrne, 1994; Erickson 1999; Levander, 2003; Keay et al, 2004b) (Fig. 12–5). There are numerous theories regarding its pathogenesis, but confirmatory evidence gleaned from clinical practice has proven sparse. Among numerous proposals that shall be further explored in this section are “leaky epithelium,” mast cell activation, and neurogenic inflammation, or some combination of these and other factors leading to a self-perpetuating process resulting in chronic bladder pain and voiding dysfunction (Elbadawi, 1997). Irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and various other chronic pain disorders may precede or follow the development of BPS/IC in some patients, but development of associated syndromes is not inevitable by any means, and their relationship to etiology is currently unknown (Warren et al, 2009; Nickel et al, 2010).

Figure 12–5 Hypothesis of etiologic cascade of bladder pain syndrome.

(From Hanno P, Lin AT, Nordling J, et al. Bladder pain syndrome. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A, editors. Incontinence. Paris: Health Publication Ltd.; 2009. p. 1459–518.)

Animal Models

The problem with animal models is how accurately they mirror the human situation. A section on animal models appears in the electronic edition along with Figure 12–6 (see the Expert Consult website![]() ).

).

Until recently, lacking an easily available animal model of the naturally occurring disease, researchers have had to devise animal models to study isolated symptoms of BPS/IC, hoping to uncover the root causes of the symptomatology (Ruggieri et al, 1990). Bullock and associates (1992) reported a mouse model in which bladder inflammation could be induced by the injection of syngeneic bladder antigen. The model demonstrated that a component in the Balb/cAN mouse is capable of inducing a bladder-specific, adoptively transferable, cell-mediated autoimmune response that exhibits many characteristics of clinical IC but was difficult to reproduce (Klutke et al, 1997).

A guinea pig model in which bladder inflammation was induced by the instillation of a solution containing a protein to which the animal had been previously immunized resulted in bladder inflammation (Christensen et al, 1990; Kim et al, 1992), as did a rat model of allergic cystitis using a local challenge of ovalbumin in previously sensitized rates (Ahluwalia et al, 1998). Changes in the rat model were dependent on mast cell degranulation and activation of sensory C fibers.

Ghoniem and coworkers (1995) studied 4 female African green monkeys challenged with intravesical acetone. Not surprisingly, they exhibited symptoms of BPS. Rivas and associates (1997) performed similar experiments using dilute hydrochloric acid in a rat model. A rat model for neurogenic cystitis using pseudorabies virus demonstrated that inflammatory changes in the spinal cord can result in dramatic, neurogenically mediated changes in the bladder (Doggweiler et al, 1998).

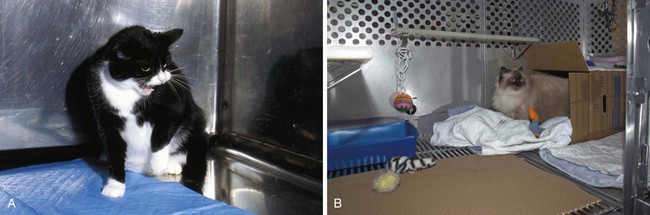

The problem with all of these animal models relates to whether they mirror the human disease to any great extent. Buffington has described what appears to be a naturally occurring animal model of BPS/IC (Fig. 12–6). Two thirds of cats with lower urinary tract disease have sterile urine and no evidence of other urinary tract disorders (Kruger et al, 1991). A portion of these cats experience frequency and urgency of urination, pain, and bladder inflammation (Houpt, 1991). Glomerulations have been observed in the bladders of these animals. GP-51, a glycosaminoglycan (GAG) commonly found in the surface mucin covering the mucosa of the normal human bladder and decreased in IC, shows a decreased expression in cats with this symptom-complex (Press et al, 1995), originally termed feline urologic syndrome. Bladder Aδ afferents in these cats are more sensitive to pressure changes than are afferents in normal cats (Roppolo et al, 2005). They also demonstrate an increase in baseline nitric oxide production in smooth muscle and mucosal strips when compared with healthy cats with evidence of altered mucosal barrier function (Birder et al, 2005).

(A and B, Courtesy of Tony Buffington.)

This is now referred to as “feline interstitial cystitis” (Buffington et al, 1999). It is associated with urinary urgency, frequency, and pain with sterile urine, bladder mastocytosis, increased histamine excretion, increased bladder permeability, decreased urinary GAG excretion (Buffington et al, 1996), and increased plasma norepinephrine concentrations (Buffington and Pacak, 2001b).

Infection

Often, a diagnosis of BPS/IC is made only after a patient has been seen by a number of physicians and treated with antibiotics for presumed urinary tract infection without resolution of symptoms (Held et al, 1990). The symptom-complex looks to the patient and physician like an infectious process (Porru et al, 2004). The epidemiology of urinary tract infection and its predominance in women mirror the BPS/IC data (Warren, 1994). The acute to subacute onset in many patients has fascinated clinicians who often associate an insidious onset with a chronic condition such as PBS/IC.

Reverse logic led some to suspect that antibiotics may be instrumental in causing IC (Holm-Bentzen et al, 1990). Most patients have been treated with antibiotics once or several times before the diagnosis is made. Numerous antibiotics, primarily in the penicillin family, can induce a cystitis (Bracis et al, 1977; Moller, 1978; Chudwin et al, 1979; Cook et al, 1979; Marx and Alpert, 1984), but no evidence has ever been documented that these antibiotics or the supposedly “surface active” nitrofurantoins or tetracyclines have any involvement in pathogenesis of IC (Ruggieri et al, 1987; Levin et al, 1988).

To determine whether there is an infectious cause of BPS certain procedures are necessary (Warren, 1994). Not just urine but bladder epithelium as well must be cultured for appropriate microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Because some organisms might be culturable yet fastidious, special culture techniques should be used. Because some organisms in urine or tissue might be viable but nonculturable, specific nonculture techniques for discovery and identification should be employed. Most important, the same procedures must be carried out in a control population.

Attempts to show an infectious etiology go back to the dawn of the disease, but the case has never been a strong one (Duncan and Schaeffer, 1997). Hunner (1915) originally proposed that IC resulted from chronic bacterial infection of the bladder wall secondary to hematogenous dissemination. Harn and associates (1973) proposed a relationship between IC and streptococcal and post-streptococcal inflammation. They produced a progressive chronic inflammation in rabbit bladders by injecting small numbers of Streptococcus pyogenes in the bladder wall. The discovery that Helicobacter pylori is related to the pathogenesis of chronic atrophic gastritis and peptic ulcer disease and that antibiotic treatment can heal ulceration (Parsonnet et al, 1991; National Institutes of Health, Consensus Development Panel, 1994; Sung et al, 1995) has continued to focus attention of researchers in IC on the possibility that an infectious etiology is not only reasonable but will ultimately be found. Studies of H. pylori itself have failed to demonstrate an association with IC (English et al, 1998; Agarwal and Dixon 2003; Atug et al, 2004; Haq et al, 2004). Wilkins and colleagues (1989) found bacteria in catheterized urine specimens and/or bladder biopsy specimens in 12 of 20 patients with IC. However, 8 of the isolates were fastidious bacteria, Gardnerella vaginalis, and Lactobacillus species and no controls were included in the study. Polyomaviruses have been reported to cause a BPS/IC-like syndrome that responds to cidofovir treatment (Eisen et al, 2009). These viruses are excreted intermittently in the urine of healthy, asymptomatic adults, making diagnosis of a true infection problematic.

Negative studies far outnumber the positive ones. Hanash and Pool (1970) performed viral, bacterial, and fungal studies on 30 IC patients and failed to substantiate an infectious cause. Hedelin and coworkers (1983) found only 3 of 19 IC patients to have urine cultures positive for Ureaplasma urealyticum and indirect hemagglutination antibodies to Mycoplasma hominis to be no greater than in controls. Potts and colleagues (2000) cultured U. urealyticum in 22 of 48 patients with “chronic urinary symptoms” and had great success in these patients (none of whom had established IC) with short courses of commonly prescribed antibiotics. Given the history of empirical use of antibiotics in the vast majority of IC patients, it is doubtful if this group represents even a small percentage of the IC diagnosed population. Nevertheless it illustrates that BPS/IC is a diagnosis of exclusion and that the urine culture is critical whereas an empirical short course of antibiotics is certainly reasonable if the patient has not already been treated for presumed infection. Empirical use of doxycycline has been successful in this situation (Burkhard et al, 2004).

The development of highly sensitive, rapid, and specific molecular methods of identifying infectious agents by the direct detection of DNA or RNA sequences unique to a particular organism (Naber, 1994) resulted in a flurry of activity into the search for a responsible virus or microorganism. Hampson and associates (1993) could find no evidence of mycobacterial involvement in 8 cases of BPS/IC using DNA probes. Haarala and colleagues (1996)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree