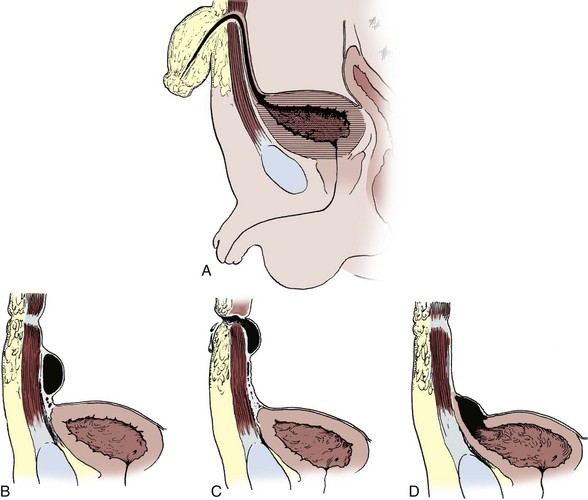

Dominic C. Frimberger, MD, Bradley P. Kropp, MD, FAAP Although anomalies of the urogenital tract are among the most commonly diagnosed antenatal malformations, the incidence of all congenital bladder anomalies is low (Carrera et al, 1995). Additionally, bladder anomalies are often a reaction to infravesical obstruction or part of a more serious disorder rather than a true isolated structural malformation. Bladder anomalies can be severe, cause urinary obstruction, and even lead to renal failure. Early detection and intervention are crucial to prevent future decompensation of the genitourinary tract. Anomalies can be detected prenatally or postnatally using ultrasound but often require voiding studies for definite diagnosis. This chapter reviews congenital bladder abnormalities in the prenatal and postnatal period and focuses on malformations not caused by infravesical obstruction. This chapter includes a discussion of the initial presentation, diagnosis, and current treatment options for the different entities and a classification based on the prenatal and postnatal presentations of bladder anomalies. Between the fourth and sixth weeks of gestation, the urorectal septum divides the endodermal cloaca into a ventral urogenital sinus and a dorsal rectum. The cranial part of the urogenital sinus is continuous with the allantois and develops into the bladder and pelvic urethra. The caudal portion gives rise to the phallic urethra in males and the distal vagina in females. Unlike in males, the entire female urethra is derived from the pelvic part of the urogenital sinus. The allantois develops as an extraembryonic cavity from the yolk sac and connects with the cranioventral portion of the cloaca, the future bladder. Around the fourth to fifth month of gestation, the allantoic duct and the ventral cloaca involute as the bladder descends into the pelvis. The descent causes the allantoic duct to elongate because it does not grow with the embryo. This epithelialized fibromuscular tube continues to become narrower until it obliterates into a thick fibrous cord, the urachus (Moore, 1982). The obliterated urachus becomes the median umbilical ligament and connects the apex of the bladder with the umbilicus (Nix et al, 1958). The fetal bladder presents as an elliptical structure filled with anechoic fluid within the pelvis. It is bordered laterally by the umbilical arteries. The pubic bones mark the anterior border, and the rectosigmoid indicates the posterior border. The bladder wall thickness should not exceed 3 mm. The mucosa and musculature present with a similar echogenicity to other structures in the pelvis (McHugo and Whittle, 2001). The bladder can be visualized in about 50% of cases in the fetal pelvis at the tenth week of gestation, concurrent with the onset of urine production (Green and Hobbins, 1988). The detection rate increases with fetal age to 78% at 11 weeks, 88% at 12 weeks, and almost 100% at 13 weeks (Rosati and Guariglia, 1996). Compared with abdominal ultrasound, transvaginal ultrasound increases the quality of the obtained images and detection rate. Because the fetal bladder empties every 15 to 20 minutes, a second ultrasound in the same setting is mandatory in case of nonvisualization of the bladder. The bladder’s diameter increases during the first trimester but should not be more than 6 to 8 mm. The fetal sex, amount of amniotic fluid, and appearance of the umbilical cord become increasingly important in the interpretation and differential diagnosis of abnormal bladder findings. Fetal sex is difficult to determine before week 14 and should not be based on the presence or absence of a phallus but on the visualization of testes (Efrat et al, 1999). The measurement of amniotic fluid as an indicator of fetal urine production is a critical portion of every antenatal ultrasound. Until 16 weeks of gestation, the amniotic fluid is mainly consistent with placental transudate, at which time it changes to predominantly fetal urine (Takeuchi et al, 1994). The umbilical cord should contain two arteries and one vein without evidence of a fluid-filled urachus (Bronsthein et al, 1990). In the first trimester, the fetal bladder is considered to be dilated if larger than 7 mm on ultrasound. If, on subsequent ultrasounds, the bladder continues to retain urine and shows no evidence of urine cycling, concern regarding obstruction should be raised. If the amniotic fluid does not increase, this may indicate the progression to oligohydramnios. Determination of the sex of the child is important because of the male gender predominance of certain diseases such as posterior urethral valves (PUVs) or prune-belly syndrome. It can be difficult to distinguish in utero if the dilatation is due to obstruction. In a retrospective study, Kaefer and colleagues (1997) described 15 patients with marked bladder dilatation in utero, 8 with and 7 without obstruction. All of the obstructed cases presented with moderate to severe oligohydramnios and a marked increase in renal echogenicity, while all but one of the nonobstructed bladders had normal amniotic fluid levels and regular renal echogenicity (Kaefer et al, 1997). Therefore fetuses with nonobstructive dilatation appear to pass enough urine to maintain renal function and adequate amniotic fluid levels throughout the pregnancy (Mandell et al, 1992). Dilatations of the fetal bladder caused by anatomic obstructions are mostly due to urethral anomalies or external obstruction. Urethral anomalies include congenital urethral strictures, anterior and posterior urethral valves, and urethral atresia. Compression of the bladder outlet region can be due to obstructing syringoceles, a sacrococcygeal teratoma or pelvic neuroblastoma, an anterior sacral myelomeningocele, a dilated vagina in a girl with a cloacal anomaly, or with rectal anomalies. The observed bladder changes are due to mechanical obstruction and affect bladder development at a critical time point, which can lead to bladder wall hypertrophy and remodeling (Pagon et al, 1979; Beasley et al, 1988; Stephens and Gupta, 1994). The term megacystis is often used to describe any condition leading to a distended fetal bladder in utero, without referring to the cause of the dilation. Historically, congenital megacystis was thought to be caused by bladder neck obstruction, leading to massive bilateral vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) and a thin bladder wall (Williams, 1957; Paquin et al, 1960). Even the describing authors recognized that surgical interventions at the bladder neck level did not change the future outcome. Harrow (1967) revisited the subject and recognized that all patients had normal urethras and complete emptying of their bladders on voiding cystourethrography. Therefore the observed reflux is not an aftereffect of obstruction, but rather the cause of the bladder dilatation from continuous recycling of the urine between the upper tract and bladder (Harrow, 1967). Congenital megacystis is defined currently as a dilated, thin-walled bladder with a wide and poorly developed trigone. The wide-gaping ureteral orifices are displaced laterally, causing massive reflux (Fig. 125–1). Bladder contractility is normal, although a majority of the urine refluxes into the ureters with each void. No neurogenic abnormalities are described. Most patients are recognized prenatally and should be placed on prophylactic antibiotics after birth (Mandell et al, 1992). Correcting the reflux often restores normal voiding dynamics and should be performed after 6 months of age. Reduction cystoplasty can be performed but is usually unnecessary (Burbige et al, 1984). Although the bladder is large enough to accommodate the tapered ureters even in a young infant, the operation can be difficult due to the bladder wall’s thinness. Congenital megacystis has been recognized in association with microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome. This syndrome is a rare congenital disorder characterized by a dilated, nonobstructive urinary bladder and hypoperistalsis of the gastrointestinal tract. The syndrome can be identified by antenatal ultrasound by the appearance of a largely dilated bladder. It has been reported mostly in females and is usually considered lethal (Srikanth et al, 1993; Lashley et al, 2000). So far there are only 10 patients who lived beyond the first year of life, and almost all need total parental nutrition. Once identified after birth, the distended bladder requires drainage via intermittent catheterization or vesicostomy placement. Long-term data concerning the urinary tract are not available due to the short life span of the patients (Bloom and Kolon, 2002). Bladder exstrophy conditions are characterized by the presence of a bladder template only. Therefore it can be suspected in the absence of regular bladder filling during fetal ultrasound. Bladder exstrophy can be distinguished from bladder agenesis by the bladder template on the lower abdominal wall, which, along with the amniotic fluid level, remains normal throughout the pregnancy (Mirk et al, 1986; Gearhart et al, 1995). The bladder can be hypoplastic due to inadequate filling or storing of urine during fetal life. Although the bladder is formed during fetal development and can be detected on antenatal ultrasound throughout pregnancy, it never reaches an adequate capacity. Conditions caused by inadequate bladder outlet resistance (e.g., severe epispadias), separation defects (e.g., urogenital sinus abnormalities), abnormalities of renal development (e.g., bilateral renal dysplasia or agenesis), or urine bypassing the bladder (e.g., ureteral ectopia) can all lead to underdevelopment of the fetal bladder. Some of these bladders grow once the malformation is corrected; however, later bladder augmentation is often required to reach adequate capacity (Gearhart, 2002). Embryologic development of bladder agenesis remains difficult to explain. The division of the cloaca into the urogenital sinus and the anorectum is apparently regular because the hindgut is usually normal. Therefore the defect can be due to either atrophy of the cranial part of the urogenital sinus or a failure to incorporate the mesonephric ducts and ureters into the trigone (Krull et al, 1988). The absence of the bladder is often associated with neurologic, orthopedic, or other urogenital anomalies such as renal dysplasia or agenesis or absence of the prostate, seminal vesicles, penis, and vagina (Aragona et al, 1988). It is a rare anomaly; only 16 live births have been reported out of the 45 known cases in the English literature. All but two were female (Adkes et al, 1988; Gopal et al, 1993; DiBenedetto et al, 1999). The defect is only compatible with life if the ureters drain ectopically into normally developed müllerian structures in the female or in the rectum in males. In surviving infants, the diagnosis can be confirmed by retrograde ureteronephrograms via the ectopic openings. Renal function can be preserved after creation of an ureterosigmoidostomy or external stoma (Glenn, 1959; Berrocal et al, 2002). Key Points: Prenatally Detected Bladder Anomalies Understanding the embryologic development of the urachus and its unique location is the key to understanding congenital urachal anomalies. The urachus is located preperitoneal in the center of a pyramid-shaped space. This space is lined by the obliterated umbilical arteries, with its base on the anterior dome of the bladder and the tip directed toward the umbilicus (Fig. 125–2). The urachal length varies from 3 to 10 cm. It has a diameter between 8 and 10 mm and can connect with one or both obliterated umbilical arteries. Microscopically, three layers can be identified. An inner layer consists of either transitional or cuboidal epithelial cells, surrounded by a layer of connective tissue. A smooth muscle layer in continuity with the detrusor muscle comprises the outer layer. Because the urachus is surrounded by the umbilicovesical fascia, disease processes usually remain contained inside the pyramid-shaped space (Hammond et al, 1941). The urachus can remain either completely open or obliterate partially, leading to the formation of cystic structures at any site throughout its course. Figure 125–2 Urachal anatomy. (From Cullen TS. Embryology, anatomy and diseases of the umbilicus. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1916.) Ashley and colleagues (2007) examined the medical records of 176 patients diagnosed with an urachal anomaly, and urachal remnants were found in 46 children and 130 adults. Children mostly presented with umbilical drainage or on physical examination, and 74% underwent excision, while 66% of adults had hematuria or pain and underwent excision in 90%. Surgical treatment in children consisted of simple excision, whereas more than 50% of adults required partial or radical cystectomy due to malignancy. They concluded that urachal anomalies present and progress differently in pediatric and adult populations and recommended urachal excision in early childhood to prevent later problems or cancer formation. There was no reported evidence that a persistent urachal remnant in childhood was the cause of later cancer development (Ashley et al, 2007). Galati and colleagues (2008) reported 23 children with urachal remnants, 10 of whom underwent excision due to symptomatic problems. In their treatment protocol, asymptomatic remnants are managed with physical and sonographic examination. They found that spontaneous resolution with nonoperative management is likely with remnants in patients younger than 6 months. However, if symptoms persist or the remnant fails to resolve after age 6 months, they recommend excision (Galati et al, 2008). Four different urachal anomalies have been described (Fig. 125–3). Figure 125–3 Urachal anomalies. A, Patent urachus. B, Urachal cyst. C, Umbilical-urachus sinus. D, Vesicourachal diverticulum.

Bladder and Urachal Development

Normal Antenatal Sonographic Findings of the Bladder

Classification of Bladder Anomalies

Prenatally Detected Bladder Anomalies

Dilated Fetal Bladder

Dilatation Caused by Obstruction

Urethral Anomalies and External Bladder Outlet Obstruction

Congenital Megacystis

Nondilated or Absent Fetal Bladder

Cloacal and Bladder Exstrophy

Bladder Hypoplasia

Bladder Agenesis

Urachal Anomalies

Bladder Anomalies in Children