Basic Evaluation of the Incontinent Female Patient

Basic Evaluation of the Incontinent Female Patient

Steven E. Swift

Alfred E. Bent

There remains considerable debate over what constitutes the minimal or basic evaluation of the incontinent female. Although there are a few published guidelines, no studies to date have determined the effectiveness of these recommendations or their relationship to therapeutic outcomes. Therefore, we are left with conflicting expert opinion regarding which, if any, testing should be done before initiating therapy for incontinence in the female patient.

However, with these limitations in mind, any basic evaluation of the incontinent female should be able to distinguish reliably among stress urinary incontinence and urge urinary incontinence. This is a particularly important point because the therapeutic interventions for the various types of incontinence are dramatically different. While surgery plays a large role in treating stress urinary incontinence, it often makes urge incontinence worse. Mixed urinary incontinence (a combination of stress and urge incontinence) cannot be diagnosed with any degree of certainty without the use of urodynamic testing. If a patient is having detrusor contractions during evaluation, multichannel urodynamic testing is required to ensure that any loss seen with cough or Valsalva is due to a weak urethral sphincter mechanism and not a detrusor contraction. In addition, the evaluation should be able to detect those uncommon forms of incontinence that require referral to a specialist.

BACKGROUND

The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) first published consensus guidelines for evaluation and management of urinary incontinence in 1992 (updated in 1996) (

1). These guidelines were drawn up by a panel of experts who based their recommendations on a critical review of the literature and on expert opinion. They recommended that a basic evaluation should include the following: a thorough history (including a voiding diary), physical examination, postvoid residual urine determination, and urinalysis. The evaluation criteria were subsequently applied retrospectively to a referral-based practice and were found to correctly diagnose only 70% of subjects with the complaint of stress urinary incontinence (

2). However, it must be remembered that these guidelines were developed for a primary care practice, but in the study mentioned, they were applied to a tertiary referral population. Therefore, it remains to be determined how effective they are for patients in a primary clinical practice. However, the study did point out some of the shortcomings of the AHCPR guidelines and demonstrated that these recommendations should be constantly tested and updated to reflect changes in our knowledge base.

Since the AHCPR’s introduction of guidelines, two other organizations have published guidelines for evaluation of the incontinent female. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) has published criteria for evaluating patients prior to surgery for stress incontinence (

3) (

Table 5.1). These guidelines are more specific to preoperative findings or criteria that should be met prior to embarking on invasive therapy. The International Consultation on Incontinence (ICI) has published an extensive algorithm (that can be viewed on line at www.continent.org open documents) on the evaluation and treatment of the

incontinent female (

4). The portion that covers the basic evaluation is complete and furthers that published by the AHCPR and should serve as a thorough clinically practical model (

Table 5.2). However, neither of these criteria sets has been evaluated in clinical practice, so while they seem complete, until tested they may prove less then reliable.

This chapter focuses on simple testing techniques for evaluating the incontinent female that

are available to most practitioners and points out some of the situations that require more specialized testing or referral.

HISTORY

All too often the patient’s history is used to diagnose the type of incontinence. The following statement is as true today as it was in 1972 and sums up the role of history in diagnosing the type of urinary incontinence in females: “urinary symptoms in the female can be extremely misleading and do not form a scientific basis for treatment …. Without some form of objective investigation, the gynecologist who relies on clinical impression is likely to submit some of his (or her) patients to ineffective surgery, and others to needless surgery” (

5). History alone is a poor predictor of the type of incontinence, and there is no question or set of questions that can adequately distinguish between the various forms of incontinence (

6,

7,

8,

9).

Severity of Incontinence

Although history is a poor predictor for the type of incontinence, it does play a major role in evaluation and treatment. A comprehensive urogynecologic history should include duration and characteristics of the incontinent episodes, frequency of incontinent episodes, use of protective devices, previous therapy, and any conditions that may predispose the patient to incontinence. Determining the nature and severity of the patient’s incontinence will help direct future therapies, with more severe symptoms suggesting more aggressive therapeutic choices and milder symptoms suggesting less invasive interventions. Although this may seem obvious, it can be overlooked. All too often a patient who has two or three incontinence episodes a year is referred to a specialist. There she undergoes an extensive evaluation with expensive testing and is offered invasive surgery or placed on daily medication simply for responding “yes” to a question about incontinence at an annual exam. Therefore, documenting the degree and severity of the problem is important before offering therapy. There are no validated or recognized severity scales to use in documenting the degree of incontinence, and there is no severity measure or cut-off for determining who will benefit from more or less invasive therapies. Instead, there exists a continuum of patients. Those with symptoms at either extreme represent obvious examples of minimal or severe incontinence for whom the decision to intervene or not is readily apparent. It is the patient with mild-to-moderate symptoms who represents the greatest challenge in determining the extent of evaluation and treatment. Therefore, documenting the degree of her problem and desire for therapeutic interventions will aid greatly in treatment planning.

Transient Causes of Incontinence

Reversible and transient causes of incontinence should be identified. These are summarized with the mnemonic DIAPPERS (

Table 5.3).

Delirium

Delirium is a state of confusion or altered consciousness characterized by acute or subacute onset. Delirium may result from many drugs or medical illnesses, and these should be considered in patients who are very poor historians or whose caretakers demonstrate concern over their change in behavior. The underlying causes of delirium may present atypically and, if unrecognized, may be associated with significant morbidity and mortality (

10). Incontinence is a symptom that may abate when the cause of the patient’s confusion is identified and treated.

Infection (Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections)

Urogenital atrophy predisposes postmenopausal women to develop urinary tract infections (UTIs). The prevalence of recurrent UTI (defined as greater then three per year) is as high as 8% to 10% in women over the age of 60 years, and it is present in 50% of female nursing home residents (

11). Symptoms of UTI in elderly patients may differ from those in younger patients. Dysuria is often absent, and incontinence may be the patient’s only symptom.

Atrophic Urethritis

Postmenopausal estrogen deficiency and atrophy of the urogenital tissues can lead to increased genitourinary tract sensitivity and irritative symptoms, including frequency, urgency, and nocturia. While atrophy does not cause incontinence per se, it does worsen symptoms, and its treatment with estrogen will resolve many of the irritative urinary symptoms (

12,

13).

Pharmacologic Causes

Virtually any medication that affects the autonomic nervous system also influences lower urinary tract function. Commonly prescribed antihypertensives, antidepressants, and sedative-hypnotics may exacerbate incontinence. Many over-the-counter multicomponent cold medications, decongestants, and antihistamines can affect the lower urinary tract. Incontinent patients should be asked about both prescription and nonprescription medication use.

One area that deserves special attention is the use of antihypertensive agents, which are commonly prescribed for older females. It has been demonstrated that patients attending hypertension clinics have a relative risk for urinary incontinence of 3.3, with alpha-adrenergic blockers (i.e., prazosin, terazosin, or doxazosin) being the primary culprits (

14). A simple change in medication from an alpha-adrenergic blocker can often provide significant clinical improvement. Diuretics, although often implicated in incontinence, may aggravate symptoms but have not been shown to have a causal relationship (

15).

Psychological Causes

Incontinence may occasionally be used to gain attention or to manipulate others. Patients may be so profoundly depressed that they do not care about continence.

Endocrine Causes

Diabetes mellitus, diabetes insipidus, and hypercalcemia may induce an osmotic diuresis that exacerbates other causes of incontinence. While this does not lead to incontinence per se, it can lead to frequency, urgency, and nocturia.

Restricted Mobility

Arthritis, hip deformity, or gait instability may impair the elderly patient’s ability to reach the bathroom. If mobility cannot be improved, a nearby commode may improve the incontinence. This is often referred to as functional incontinence.

Stool Impaction

Fecal impaction is a common cause of urinary incontinence in bedridden or immobile patients. As the sigmoid and rectum enlarge, they act as a pelvic mass, compressing the bladder and exacerbating other forms of incontinence. It should be suspected in the patient who develops fecal oozing and urinary incontinence with a palpable bladder (

16).

VOIDING DIARY

The voiding diary is a helpful evaluation tool for documenting and measuring the severity of incontinence. There are several different techniques for performing a voiding diary. The frequency of urinary episodes can be collected over 3 to 7 days and/or the amount of liquid intake and urine production can be recorded over 1 to 2 days. A 1-week record of leak episodes and voiding is highly reliable for demonstrating urinary frequency, nocturia, and number of incontinent episodes; however, it cannot diagnose the type of incontinence (

17). A 3-day voiding diary has demonstrated equivalence to a 1-week diary for documenting frequency and nocturia (

18). A 24-hour record of fluid intake and voided volumes has a weak correlation with frequency of voids and incontinent episodes, but it does measure the fluid intake and voided bladder volumes (

19). A fluid intake of greater than 4 L/day mandates consideration of diabetes insipidus, and frequent small voids can point to a diagnosis of interstitial cystitis.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical examination should include a general physical examination, local neurologic testing, pelvic examination, cotton swab test, postvoid residual, and cough stress test.

General Physical Exam

An overall assessment of the patient is important. This includes a comment about her general state of health, mobility, and cognitive status. Subjects in poor health with limited mobility will require a different set of goals and therapeutic options than a more active, healthy patient. In addition, there are a few other aspects of the general physical that should be noted. An abdominal examination revealing a large abdominopelvic mass or significant ascites will need to be evaluated and addressed prior to embarking on therapy for incontinence. Attempting to treat urinary frequency and urgency

with a large mass filling the pelvis or abdomen and compressing the bladder will be met with frustration and poor treatment outcomes. Significant peripheral edema in conjunction with a 24-hour voiding diary that demonstrates nocturia or nocturnal urge incontinence suggests that the patient is mobilizing fluid in the recumbent position. Mobilizing this fluid before bed may aid in the treatment of her symptoms. The individual with limited mobility requires special consideration in any treatment plan. Use of bedside commodes and teaching better transfer techniques are often all that is necessary to treat incontinence.

Neurologic Examination

A brief focused neurologic examination is recommended to screen for neurologic disease but has a low detection rate in the patient with no history of neurologic diseases. If the history or general assessment of the patient suggests a neurologic disorder, then a thorough neurologic examination is required. If the patient appears neurologically intact during the history and there is no past medical history of a significant neurologic insult, then a brief neurologic examination as outlined below is satisfactory.

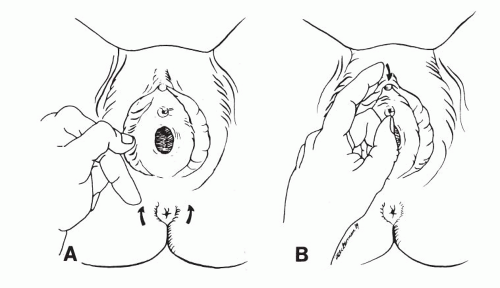

A brief neurologic examination consists of deep tendon reflex testing of the lower extremities and simple assessment of perineal sensation and clitoral or anal sphincter reflex.

The reflexes to be tested include the knee, ankle, and plantar responses. Any asymmetry of the reflexes may closely reflect the nature of bladder dysfunction. In supranuclear lesions, there is hyperreflexia of the deep tendon reflexes. This is often associated with uninhibited detrusor contractions as demonstrated by cystometry.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access