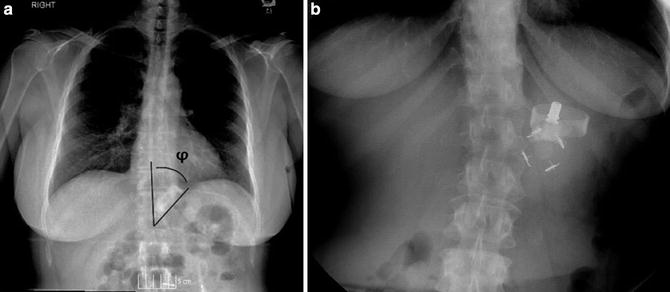

Fig. 16.1

A normally positioned gastric band with an 8 o’clock to 2 o’clock orientation and passage of oral contrast

Fig. 16.2

(a) φ (phi) angle is measured to determine whether the band is correctly positioned. This is the angle formed on frontal radiographs between the vertical axis of the spine and the bottom of the gastric band. (b) Prolapse exhibiting a large φ (phi) angle and 10 o’clock to 4 o’clock orientation

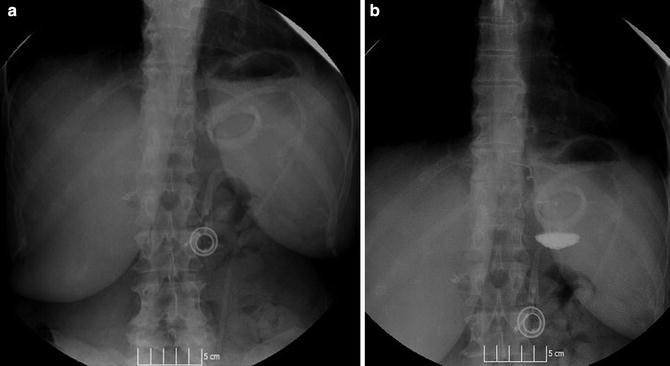

Fig. 16.3

(a) “O” sign suggestive of a posterior gastric band prolapse. (b) “O” sign with pooled contrast and air bubble

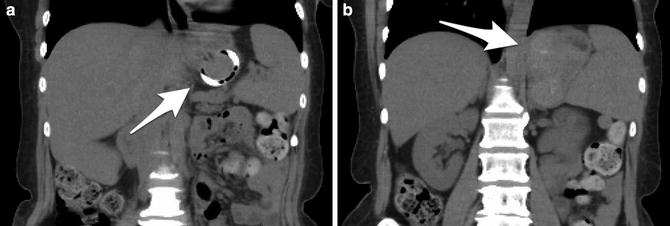

Fig. 16.4

CT scan demonstrates a vertically rotated gastric band (O sign) and a large posterior pouch

16.2 Management

The natural history of untreated prolapse remains unclear. Although this question is inadequately addressed in the literature, this author’s experience suggests that patients with delayed follow-up or who refuse intervention do not appear to be at a higher risk of gastric compromise or the need for emergent intervention. Despite this, we continue to advise all patients found to have a prolapse to undergo some form of treatment to potentially avoid the catastrophic complication of progressive prolapse, leading to gastric ischemia, necrosis, and gastric perforation [19].

Patients who present acutely with a severely prolapsed band, abdominal pain , and obstruction and who do not respond to band decompression require emergent surgical intervention. Our practice in these rare cases is to remove the band and all of its associated components. Under these acute circumstances we do not routinely give any other revisional options to the patient. The reason for this is that we have found that the prolapsed section of stomach is edematous and friable and not in optimal condition to be manipulated and stapled. Also, these patients are often dehydrated and nutritionally depleted and thus not in optimal condition to undergo a revisional bariatric procedure. The primary focus in these patients, as with any surgical emergency patients, should emphasize lifesaving maneuvers; additional bariatric surgery should be considered on an elective, interval basis only. The remaining section of this chapter deals with patients presenting with a more chronic form of prolapse.

Management of chronic LAGB prolapse involves one of the four options:

1.

A conservative non-operative approach

2.

Band removal

3.

Band revision (re-banding)

4.

Band removal with conversion to an alternate bariatric procedure

16.3 Conservative Treatment

Nonsurgical management should be the first step in managing patients who present with prolapse. In our practice nonsurgical or conservative management includes band decompression and commencement of a strict liquid diet for a month. This is then followed by re-imaging and slow re-inflation of the band if the prolapse has resolved. Although the efficacy of this approach for patients presenting with a true prolapse has been questioned by some [20], the authors routinely follow this algorithm with acceptable results. The theory behind this approach is that since food impactions due to inadequate food processing led to obstruction with herniation and incarceration of the proximal stomach above the band [9], decompression and thereby relaxation of the “hernia ring” followed by a liquid diet will allow the pouch to spontaneously reduce. Some groups have also reported on a technique using endoscopy and gastric insufflation to reduce the prolapse with reasonable outcomes [21].

If conservative management is successful, patients must be aggressively counseled and strongly encouraged to stick with a multidisciplinary nutritional, psychological , and medical approach. This last point cannot be overstated. Revisional surgery should only be considered as a last resort and this must be made very clear to the patient: “there is no surgery safer than no surgery.”

16.4 Surgical Treatment

If conservative management fails, surgical treatment becomes the only remaining option. Helping patients choose between band removal , re-banding, or an alternative bariatric procedure is difficult and has traditionally been more based on patient preference and surgeon bias than published evidence. This is primarily due to the fact that data on LAGB prolapse and its optimal management is limited by small sample sizes and widely varying results.

Despite initial hopes that the LAGB would lead to durable lifestyle changes and by extension weight loss maintenance even after explantation, the literature suggests that patients opting for band explantation do not retain their weight loss and comorbidity resolution. In a report by Aarts et al. [22], not only had all 21 patients who had their band removed not been able to maintain their weight loss but their median weight had actually increased after 5 years of follow-up. This led them to recommend that all band explantations should be combined with a revisional bariatric operation.

Some have advocated an algorithmic approach to choosing a revisional procedure. In patients who were initially successful with the band but then experienced band complications such as prolapse, another restrictive procedure can be considered, e.g., re-banding or revisional laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (re-LSG). Patients who failed to achieve their weight loss goals however may instead be better served with a revisional laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (re-LRYGB) because of the added malabsorptive component [23]. This has also been the author’s practice. Future studies will be required to definitively answer this question.

Because of extensive adhesion formation and fibrotic reaction surrounding the band, any revisional bariatric operation is difficult and often tedious, requiring advanced laparoscopic skills and an excellent knowledge of UGI anatomy. Revisional bariatric surgery should only be undertaken by experts and only after an extensive discussion with the patient regarding risks. The consent process should include a discussion of bleeding , gastric or esophageal perforation, and injury to the vagus nerve. These injuries may lead to significant morbidity and even death.

Another very important issue related to revisional bariatric surgery is managing patient expectations as far as weight loss and complication rates. Patients often have unrealistic expectations that their results and risk with revisional surgery will mimic those of their friends who have undergone primary bariatric surgery. Pros and cons must be weighed very carefully and discussed at length with each individual patient. Although true about any bariatric surgery, this is particularly true for revisional bariatric surgery. Lastly, we specifically discuss the paucity of data available regarding revisional surgery and encourage patients to consider this carefully before deciding on revisional surgery.

16.5 Technique

All revisional surgery involves the following common steps.

1.

Lysis of adhesions between the liver, the anterior gastric wall, and the capsule of the band: These are often extensive.

2.

Repair of hiatal hernia which is particularly common in patients with prolapse.

3.

Unbuckling of the band.

4.

The region of the gastric band capsule consists of fibrotic tissue which must be divided and dissected off of the gastric serosa.

5.

Dissection of and clearance of the angle of His with visualization of the left crus.

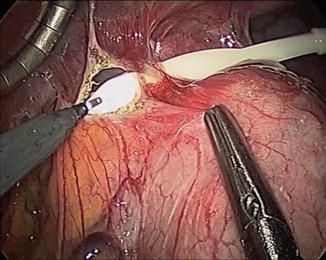

Dismantling the wrap and resecting it or at least disrupting the band capsule is the most difficult and delicate part of revisional surgery. Some of the tricks and tips we use include the following:

1.

The use of L-hook electrosurgery: The band is made of silicone and therefore is very amenable to the use of hook electrosurgery to lyse adhesions using the band as a baffle. The electrical current will not pass through the band, thereby protecting underlying structures (Fig. 16.5).

Fig. 16.5

The hook electrocautery can be used to lyse adhesions directly overlying the band using the band as a baffle

2.

Adhesiolysis can be performed aggressively outside of the band ring. Other than where the wrap envelopes the band, anterolaterally and to the left of the buckle, the stomach/esophagus will always be contained within the band ring. This may be especially helpful as the surgeon comes around the buckle medially just adjacent to the caudate lobe and on the right crus.

3.

The hiatus is an extremely important landmark and is most often a virgin surface just cephalad to the adhesions formed around the band (Fig. 16.6). Recognizing the hiatus helps keep dissection away from important structures such as the esophagus and IVC.

Fig. 16.6

Identifying the hiatus is an extremely important landmark and is most often a virgin surface just cephalad to the adhesions formed around the band

4.

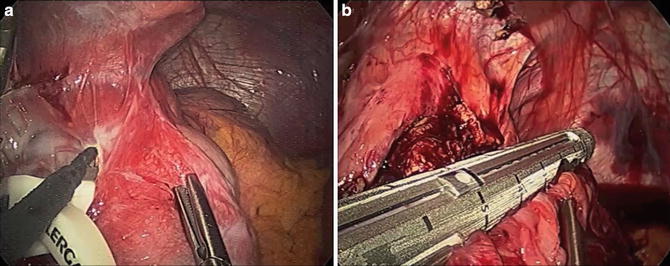

We use extreme care in releasing the gastro-gastric wrap and use sharp dissection and electrocautery exclusively in areas that are clearly translucent, i.e., fibrous capsule (Fig. 16.7a). If a segment of tissue is suspected of being the gastric wrap, we tend to divide it using a stapler rather than taking the risk of injury and leak (Fig. 16.7b).

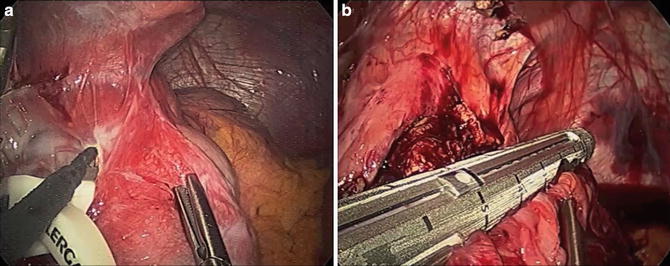

Fig. 16.7

(a) Extreme care should be exercised in releasing the gastro-gastric wrap. Sharp dissection and electrocautery should only be sued in areas that are clearly translucent, i.e., fibrous capsule. (b) Any area even suspected of being gastric wrap, we tend to divide using a stapler rather than taking the risk of gastric injury

5.

Unbuckling of the band can be very helpful. Doing this without damaging the band is important if the plan is to reuse the band. The original Lap-Band ® and Realize® bands were significantly more difficult to unbuckle as compared to the current AP band, where a simple traction-countertraction maneuver suffices.

6.

Stripping the capsule can be tedious, but is particularly important for patients undergoing revisional sleeve or bypass. Some authors feel that this stripping must be circumferential and not just on the anterior surface (Figs. 16.8, 16.9, 16.10, and 16.11).

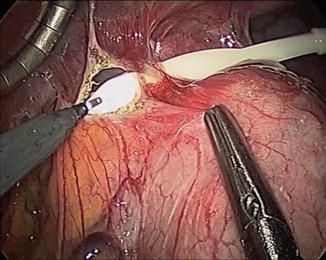

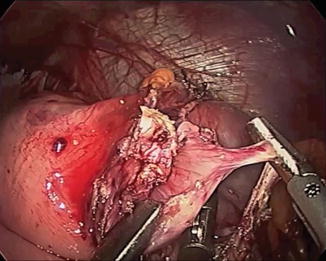

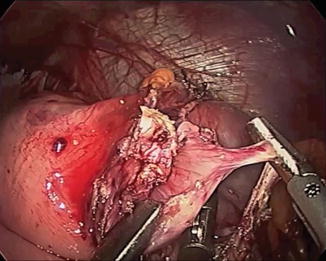

Fig. 16.8

Stripping the capsule can be tedious, but is particularly important for patients undergoing revisional sleeve or bypass. This stripping must be circumferential and not just on the anterior surface

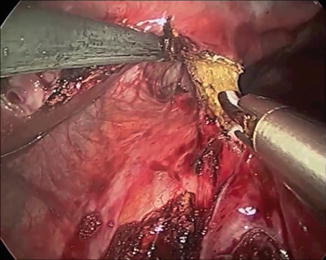

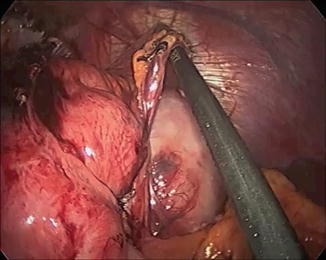

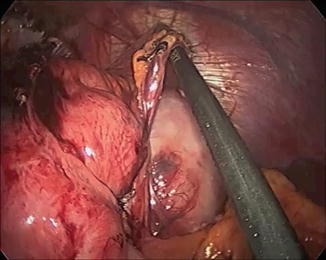

Fig. 16.9

Stripping of the capsule then proceeds laterally

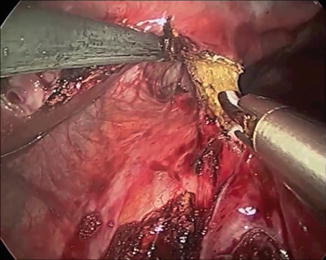

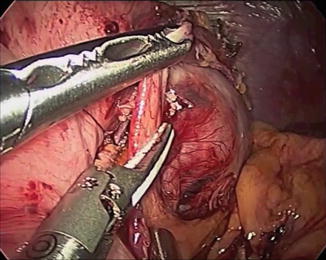

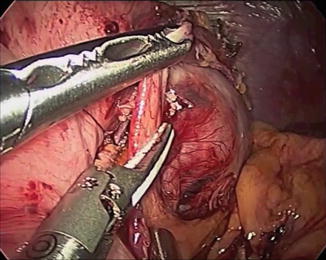

Fig. 16.10

There is often an adhesive band extending around the prolapsed segment of stomach which also must be divided

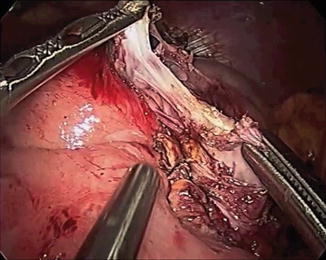

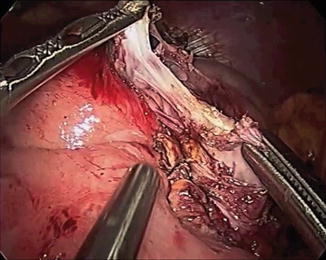

Fig. 16.11

Finally the capsule is stripped posterolaterally to complete the freeing of the prolapsed stomach

7.

Leaving the band in situ may help identify the posterior aspect of the capsule. Even in the scarred posterior retroperitoneal attachments of the proximal stomach where the anatomy is obscured, the band can be easily palpated and then, as described above, electrocautery used on the band to divide the capsule in a very safe manner.

16.5.1 Re-banding

As described above, the evidence for re-banding is lacking and results vary in the literature. In a recent paper, Suter [24] described his experience with a small number of patients (9 patients) undergoing re-banding after prolapse. After a mean follow-up of 20 months, 6 (66.6 %) had insufficient weight loss and only 2 (22 %) went on to lose further weight. More than half of these patients required further surgery, including band removal in three and conversion to gastric bypass in two. He concluded that re-banding for prolapse produces disappointing results in midterm follow-up.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree