Fig. 8.1

(a) Double balloon enteroscope. (b) Single balloon enteroscope

The technique for double balloon enteroscopy was developed by Dr. Hironori Yamamoto in Japan and was initially described in 2001 [1]. It consists of a series of push and pull maneuvers where the endoscope is advanced through the overtube as far as possible. The balloon on the scope is then inflated, anchoring the tip of the scope inplace. The overtube is then advanced to the end of the enteroscope and the overtube balloon inflated. With both balloons inflated, the scope and overtube are pulled back, pleating small bowel over the system. The scope balloon is then deflated and the scope tip advanced. This series of maneuvers is repeated as the scope is advanced into the small bowel. With single balloon enteroscopy there is only the overtube balloon to anchor the system and techniques of suctioning and tip deflection are used to help anchor the tip while maneuvering the overtube and shortening [2].

Both DBE and SBE can be performed via the oral (antegrade) or rectal (retrograde) approaches and thus allows for assessment of a significant portion of the small intestine. In general, both approaches are required to achieve a total enteroscopy as it is rare to be able to traverse the entire small intestine from the oral route alone [3]. Reported total enteroscopy rates using a combined approach range from approximately 18–92 % for DBE [4–7], with an average of 44 % reported in a recent systematic review [3]. DBE has been compared to SBE in two randomized trials showing discordant results: with the trial reported by Domagk et al. showing no difference between DBE and SBE in 130 patients [7] while the trial reported by May et al. showed a total enteroscopy rate three times higher in the DBE group in 100 patients. The diagnostic yield was similar between both groups in this study [6]. Overall, the consensus is that double balloon does offer some advantage over single balloon enteroscopy in the potential depth of insertion.

The choice of the antegrade or retrograde route in part depends on the indication and anticipated location of the pathology. The procedures are usually done under conscious sedation, although general anesthesia has been used in many series. The choice of sedation does not appear to influence the outcome of the procedure and should be tailored to what is most appropriate for the patient. For both DBE and SBE, estimated depths of insertion for the antegrade route are approximately 2.5–2.7 m and retrograde 1.3–1.9 m [2, 8], although ranges vary widely. Average procedure times are in the range of 60–90 min for either approach and it is recommended that the retrograde study not be done on the same day as the antegrade study [9]. Bowel preparation is only required for patients undergoing retrograde studies and it is important to ensure a very good bowel preparation as residual debris can cause undue friction between the scope and overtube making smooth advancement of the scope difficult [9].

Indications for Deep Enteroscopy in Crohn’s Disease

Diagnostic Indications

Our ability to evaluate small intestinal Crohn’s disease has improved dramatically over the last few decades with the advent of wireless capsule endoscopy, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) enterography. Although wireless capsule endoscopy (WCE) has been shown to be accurate in defining small bowel Crohn’s disease, it is not feasible because of the risk of capsule retention in up to 40 % of patients [10, 11]. It also does not allow for tissue sampling in cases where the diagnosis is unclear. Several groups have tried to define the role of these various modalities and have published recommendations on their use in Crohn’s disease [12, 13]. The role of deep enteroscopy remains to be precisely defined in patients with Crohn’s disease, but it does have a role both for diagnosis and therapy in selected patients. Recent consensus guidelines suggest it be used when biopsies are required from suspected involved areas or for dilating strictures when these areas cannot be reachedwith standard endoscopes [14, 15]. A summary of possible indications in listed in Table 8.1.

Table 8.1

Indications for deep enteroscopy in patients with known or suspected IBD

Diagnostic indications • Biopsy of abnormal small intestine in patients with suspected Crohn’s disease and abnormal imaging • Assess abnormal small intestine in patients with known Crohn’s disease not responding to therapy • Assess response to therapy in patients with isolated small intestinal Crohn’s disease • Evaluate obscure bleeding in patients with known Crohn’s disease |

Therapeutic indications • Stricture assessment and dilatation • Treatment of small intestinal bleeding • Retrieval of retained wireless video capsules |

From a diagnostic standpoint deep enteroscopy should be considered in patients with suspected Crohn’s disease who have abnormal small bowel imaging and negative gastroscopy and/or ileo-colonoscopy. In this situation the results may help to confirm a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease or rule out other possible infectious or neoplastic conditions. In patients with known Crohn’s disease, it can be used to directly evaluate abnormal areas identified on small bowel studies when this information is needed to aid in decision-making regarding changes in therapy or to rule out other mucosal complications such as lymphoma. Repeat examination can help to evaluate for mucosal healing and response to therapy, as CT and MR enterography are not sensitive for the evaluation of mild disease [16–18]. Deep enteroscopy has also been used to evaluate obscure bleeding in patients with known Crohn’s, with reported diagnostic yields of approximately 40 % [19]. A variety of mucosal findings have been described with deep enteroscopy in patients with Crohn’s disease and include erosions, apthoid ulcers, round and longitudinal ulcers, cobblestoning, strictures and tumors [20] (Figs. 8.2, 8.3 and 8.4).

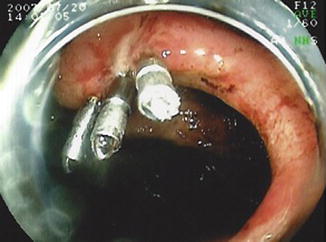

Fig. 8.2

Antegrade DBE showing an isolated Crohn’s ulcer in the mid-jejunum

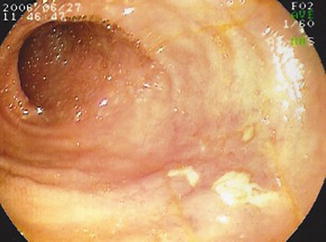

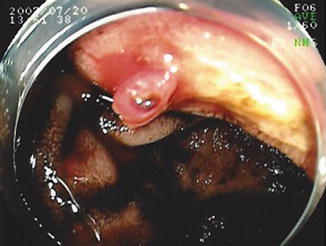

Fig. 8.3

Retrograde DBE showing an anastomotic ulcer in the mid-ileum

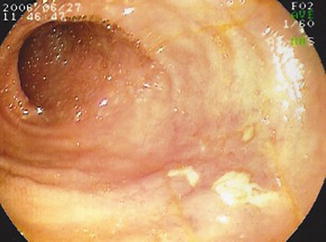

Fig. 8.4

Retrograde DBE showing a fibro-stenotic stricture

Several authors have examined the clinical impact of deep enteroscopy in patients with Crohn’s diseaseand have found that the findings at enteroscopy have a diagnostic yield ranging from 44 % to 77 % [19, 21]. Results of deep enterosopy can lead to changes in therapy in up to 75 % of patients [16, 22]. The diagnostic yield appears to vary depending on the indication of the deep enteroscopy, with Manes et al. reporting a diagnostic yield of DBE at 40 % for evaluation of obscure bleeding compared to 50 % for diagnosis of small bowel lesions and 100 % for the evaluation of small intestinal strictures in patients with Crohn’s disease [19]. One study used DBE to confirm mucosal healing after stepping up therapy in patients with isolated small bowel Crohn’s [16].

Therapeutic Indications

Balloon dilatation of strictures in Crohn’s disease has been shown to be an effective alternative to surgery, with a systematic review showing technical success in 86 % and long-term clinical success in 58 % of reported patients [23]. Although the majority of strictures in patients with Crohn’s disease are ileo-colonic in location, a small percentage of Crohn’s patients will have strictures isolated to the small bowel and deep enteroscopy provides a means to endoscopically access these strictures and perform through-the-scope (TTS) balloon dilatation. The technique for balloon dilatation has been outlined by Sunada et al. [20]. Fluoroscopy should be used to guide the dilatation. Once the stricture is reached by balloon enteroscopy, if the scope cannot be passed through the stenosis, it is helpful to inject contrast through the scope to outline the stricture and bowel beyond. A guidewire should then be passed beyond the stricture and the balloon subsequently positioned using both endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance. Initial dilatation size should depend on the severity of stricture, but in general, most authors have dilated to 15–18 mm. For very tight strictures, an initial dilatation of 10–12 mm is recommended, which can then be enlarged to 15–18 mm at a subsequent procedure (Video 8.1). The end point primarily depends on the patient’s clinical response. Several centers have reported their results for stricture dilatation in patients with Crohn’s disease. Approximately 20–30 % of patients referred for stricture dilatation are not candidates either due to failure to reach the stricture or because the strictures are long or predominantly inflammatory in nature [24]. For those patients in whom dilatation is technically possible, the clinical success ranges from 68 % to 79 %, with approximately 25–35 % of patients requiring a second dilatation [24–26]. Complications have been minimal, with only one reported perforation after DBE balloon dilation in a series of 11 patients [25].

Deep enteroscopy can also be used to treat obscure bleeding in patients with Crohn’s disease. Bleeding can result from Crohn’s ulcers, anastomotic ulcers or unrelated vascular lesions. Similar to obscure bleeding for other indications, bleeding can be treated with Argon plasma coagulation, endoscopic clips or injection therapy (Figs. 8.5 and 8.6). There is no data on the outcomes of treatment of bleeding using deep enteroscopy, specifically in patients with Crohn’s disease. In unselected patients with bleeding vascular lesions of the small intestine, DBE has been reported to have an initial success of 97 %, with a 46 % rebleeding rate at 36 months [27]. Re-bleeding rates in patients with Crohn’s disease would likely be higher and depend on the etiology of the bleeding and if other treatment is available to address the underlying disease (Video 8.2).

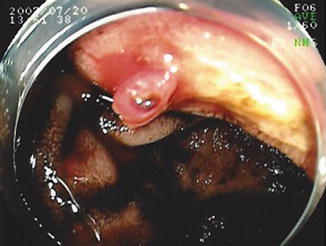

Fig. 8.5

Antegrade DBE showing an anastamotic ulcer with visible vessel

Deep enteroscopy has been used to successfully retrieve retained video capsules in patients, some of whom have had Crohn’s disease strictures as the cause for the capsule retention [28]. This is usually done via an antegrade approach in patients with symptomatic obstruction since they cannot be properly prepped for a retrograde procedure. Patients with capsule retention without bowel obstruction who can tolerate a bowel preparation can undergo either approach depending on the location of the retained capsule. Stricture dilatation may be necessary to reach the capsule.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree