occurs over bony prominences of the hands and feet of adolescents; (c) the Fordyce type characteristically affects the scrotum but may “spill over” to the perineum; (d) angiokeratoma circumscriptum classically affects the lower extremities and is present at birth; and (e) the solitary and multiple types appear on the lower extremities of individuals in the second

to fourth decades of life. Regardless of subtype, the lesions are characterized histologically by the presence of dilated vessels, which are primarily restricted to the uppermost dermis and are bordered or enclosed by elongate rete ridges (Fig. 5.4, e-Fig. 5.9). Over time, the overlying epidermis often becomes hyperkeratotic and, sometimes, papillomatous, such that the lesions are mistaken for common warts in other locations and condylomas in the genital region. The process is commonly regarded as a form of telangiectasia rather than a true neoplasm. The lesions can be hemorrhagic and painful, sometimes requiring ablative treatment (12).

FIGURE 5.3 Hidradenoma papilliferum. At first glance, these lesions are reminiscent of adenocarcinomas, but the papillary fronds are coated by two layers of cells. |

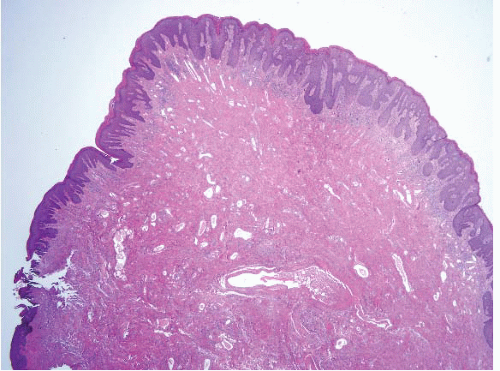

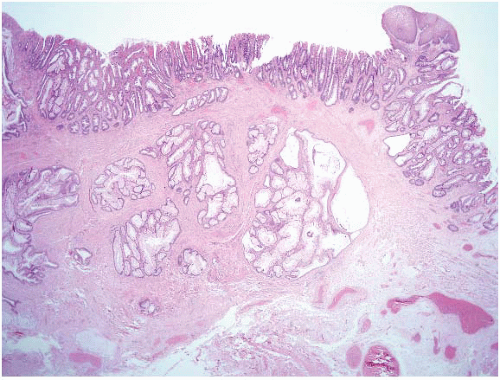

FIGURE 5.5 Inflammatory cloacogenic polyp. This is an anorectal variant of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (discussed in Chapter 4) and is a type of mucosal prolapse polyp. Note the squamous epithelium in the upper right portion of the field. There are also benign crypts herniated into the submucosa in a colitis cystica profunda pattern. This pattern can suggest adenocarcinoma but the glands are benign. |

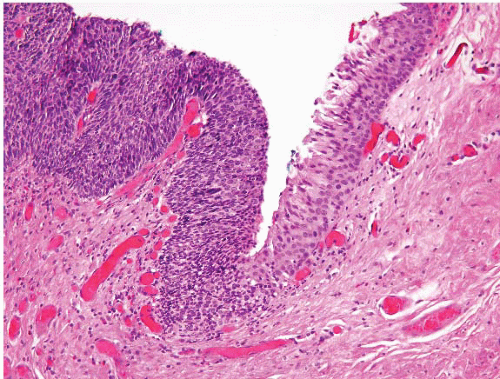

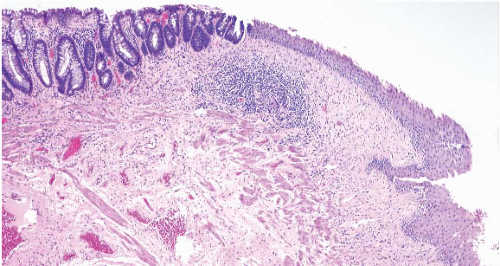

FIGURE 5.6 Inflammatory cloacogenic polyp with Anal intraepithelial neoplasia, grade 3 (AIN 3) on the surface. Mucosal prolapse polyps show strands of smooth muscle in the lamina propria between individual crypts, such that the glands often show acute angles (“diamond-shaped crypts”). As for the hemorrhoid in Figure 5.1, anal lesions should always be scanned for areas of AIN. |

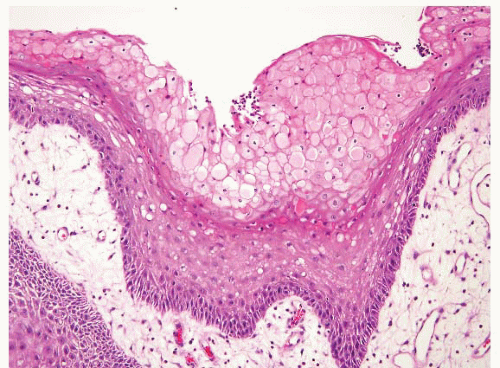

superficially resemble viral cytopathic effect and should not be diagnosed as such (Fig. 5.9, e-Fig. 5.15). When these are examined, as stressed above, be sure to always evaluate the overlying mucosa for anal intraepithelial neoplasia (Fig. 5.10).

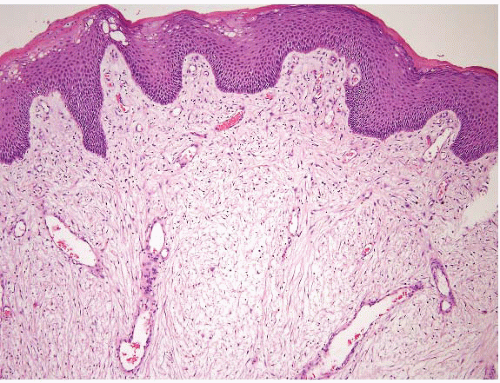

FIGURE 5.7 Fibroepithelial polyp. These are essentially skin tags of the anal area. Like skin tags elsewhere, their stroma can be cellular and contain atypical cells. |

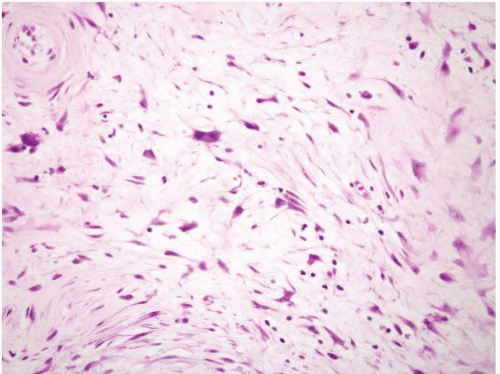

FIGURE 5.9 Fibroepithelial polyp. Reactive changes at the surface can be reminiscent of viral cytopathic effects of human papillomavirus (HPV). Note, however, that the nuclei of the damaged cells on the surface are small and uniform in contrast to true koilocytes. Compare them to the HPV-affected cells in Figures 5.15, 5.16 and 5.17. |

much lower frequency of AIN in condylomas excised from HIV-negative women, 8.3% (2.8% high grade) (20). It is frequently from this HIV-positive population that pathologists receive anal biopsies to evaluate. At least half of the homosexual male HIV population has anal HPV lesions (17,18), and low-grade lesions progressed to high-grade lesions in about 20% of such patients in 2 years in one study (18), but it seems that very few of these in situ lesions progress to invasive carcinoma; patients most at risk for progression to invasion are those with immunosuppressed states (21). Additionally, women with cervical/perineal dysplasia are at risk for anal dysplasia regardless of a history of anal intercourse or immunosuppression with prevalence ranging from 17.4% to 59.2% (22,23). The main reason to treat these lesions is the aggressive nature of invasive carcinomas in these individuals once invasion ensues. The effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on these lesions remains unclear, but is not necessarily beneficial (24). Anal intraepithelial lesions are summarized in Table 5.1. As noted above, their common denominator is HPV, but the factors that determine whether any given infection manifests, such as bowenoid papulosis versus invasive squamous cell carcinoma, remain obscure.

a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor. Lu et al. immunohistochemically studied 29 cases of squamous cell carcinoma of the anorectal region for the expression of p16. The tumor cells exhibited a strong and diffuse nuclear stain (with some cytoplasmic positivity) for p16 in all 29 cases (100%). HPV DNA was detected in every case (100%), with 25 cases (86%) harboring type 16. These and similar other (26) observations indicate that overexpression of p16 is commonly associated with high-risk HPV infection, which may serve as a useful surrogate biomarker for identifying squamous

cell lesions harboring HPV DNA. As such, in intraepithelial lesions, p16 can be a helpful adjunct in separating reactive from AIN lesions (e-Figs. 5.39 and 5.40). When positive, this immunostain is predictive of dysplasia in anal cytology specimens, but the sensitivity and specificity are less than optimal (27). Tandem ki-67 stain can also be helpful. At our

institution, high-grade (AIN II or III) lesions are the threshold for offering treatment, and we sometimes use these stains to confirm an impression of a high-grade lesion. We do not routinely perform HPV testing on such cases, but do so if there is a specific request (e-Fig. 5.20). Interestingly and similarly to some colon cancers, Zhang et al. reported high rates of DNA methylation

in cases of squamous cell carcinoma and high-grade AIN. DNA methylation of the genes IGSF4 and DAPK1 was specific for high-grade AIN and squamous cell carcinoma as methylation of these genes was absent in cases of low-grade AIN and in normal mucosa (28). Current treatment options for AIN include electrofulguration, infrared coagulation, immunomodulation therapy with imiquimod 5% cream, and surgical excision.

TABLE 5.1 Squamous “Precursor” Lesions Encountered on Anal Area Biopsies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

FIGURE 5.11 Anorectal transition zone. There is colorectal mucosa on the left and squamous mucosa on the right. There is a brief central zone that is transitional. |

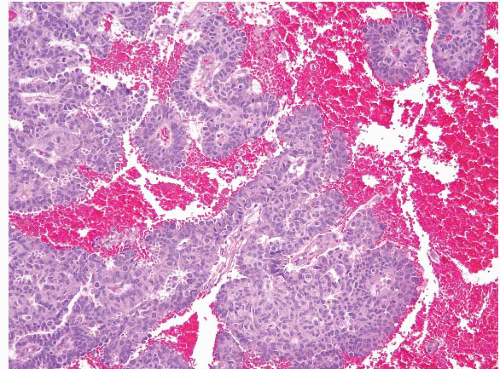

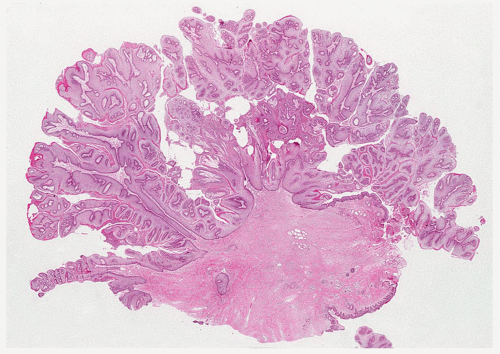

FIGURE 5.13 Anal condyloma. The lesion is exophytic with a pattern reminiscent of a cauliflower. It contains papillary fronds with fibrovascular cores. |

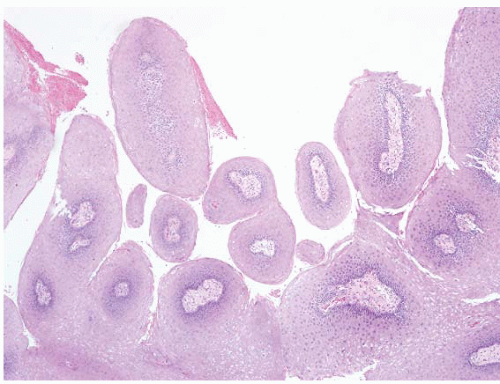

FIGURE 5.14 Anal condyloma. This example is less exophytic than the lesion seen in Figure 5.13 but still shows papillary fronds with vascular cores. |

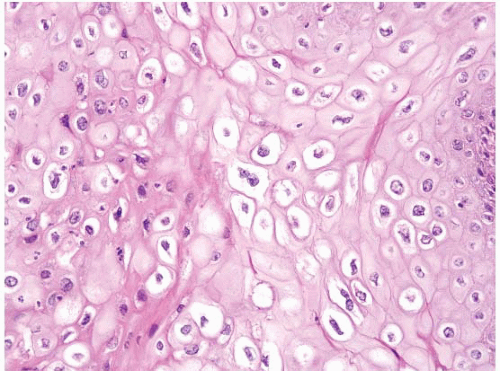

FIGURE 5.15 Anal condyloma. The HPV viral cytopathic effect is readily apparent here. The nuclei are enlarged, occasionally binucleate, and surrounded by perinuclear cavities. |

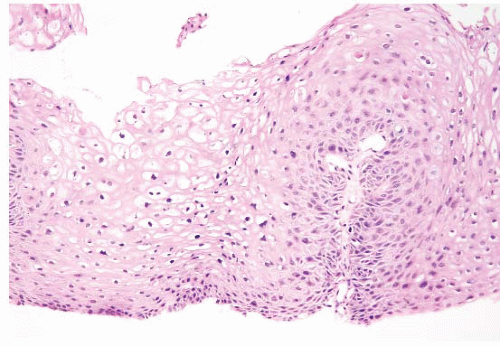

FIGURE 5.16 Anal flat condyloma/anal intraepithelial neoplasia, grade 1 (AIN 1). The cytologic changes in this example are more subtle than those in the one seen in Figure 5.15

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|