Anterior Wall Support Defects

Stephen B. Young

Scott M. Kambiss

ANATOMY

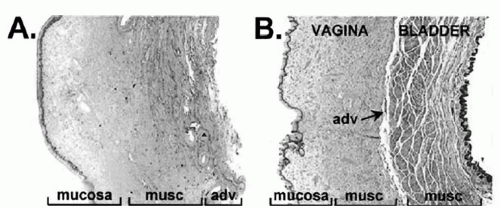

For many years gynecologists have debated the composition and nature of vaginal tissues in relation to the urinary bladder. There are two distinct schools of thought: one group believes that between the bladder and the vagina there exists a fascial layer, and the other group does not. The “fascialists” have termed this layer the pubocervical fascia in the anterior compartment—one part of a total supportive pelvic skeleton, the “endopelvic fascia.” To further understand the vaginal anatomy as it relates to the urinary bladder, histologic studies have been performed to determine the true composition of these tissues. Weber and Walters reported their results of microscopic examination of full-thickness sections of the vagina and urinary bladder taken from autopsy specimens (1). Weber and Boreham et al separately found that the anterior vaginal wall was composed of three layers: epithelium, muscularis, and adventitia. Immediately deep to the vaginal adventitia is bladder adventitia. Deep to that is detrusor muscle and finally bladder mucosa. They found no fascia (Fig. 28.1) (1,2).

Laterally, the anterior vaginal walls are attached by fibrous connections (endopelvic fascia) to the levator ani at the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis (ATFP) or the “white line.” The ATFP extends from the underside of the pubic symphysis and inferolateral pubic bone to the ischial spine bilaterally (3). In addition, the cardinal and uterosacral ligament complex helps support the upper vagina with its attachments to the sacrum and lateral pelvic walls.

Progress has occurred during the past 15 years in our understanding of anterior pelvic floor support and prolapse with research utilizing anatomic dissection and histologic/histochemical microstudy, a variety of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques with computer applications, and other basic science work (e.g., biomechanics and muscle physiology). John DeLancey has brought us an evolution in pelvic floor anatomic understanding from his elegant cadaver dissection work (4). He has used MRI studies to help resolve longcontentious issues over the presence or absence of fascia, the constituents of the pelvic floor support “ligaments,” the great importance of the levator ani muscles, and the entire panoply of pelvic floor support (5,6). He and biomechanical engineer John Ashton Miller have increased our knowledge of pelvic function. MRI also allows for specific measurements to be made within the anterior compartment. In 1995, Aronson et al clearly demonstrated normal and abnormal pelvic anatomy utilizing continent and incontinent women including paravaginal defects (7). There is a great deal more that MRI and other research tools will teach us about pelvic floor anatomy, function, and pathophysiology.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY: TYPES OF DESCENT

Prolapse of the anterior vaginal wall is the most common single site of pelvic organ prolapse (POP), with an overall prevalence of 33.8% (8). It may occur alone or more commonly along with other pelvic defects. Early grades may be asymptomatic, yet more advanced anterior prolapse may cause multiple mechanical and functional symptoms. In the early 20th century, George White described anterior pelvic floor descent as being due to overstretching and thinning out of the anterior vaginal wall and other supports of the bladder to descend in the form of a hernia (8,9).

The anterior vaginal wall is lined on the vaginal lumen side by a nonkeratinizing squamous epithelial

lining that ends at the lamina propria. The muscular layer lies beneath the lamina propria and consists of mostly smooth muscle fibers along with small amounts of a collagen and elastin connective tissue (1). When this muscularis is surgically dissected from the epithelium during a split-thickness anterior colporrhaphy dissection, it is often referred to as “pubocervical fascia” (10). The third layer is known as the adventitia. It is loose areolar tissue and is shared by the bladder. Boreham et al compared specimens taken from the anterior vaginal cuff in both normal subjects and those with prolapse (2). Following immunohistologic review it was noted that women with prolapse had a significantly reduced fraction of smooth muscle, disorganized smooth muscle bundles, and decreased alpha-actin staining in the muscularis as well as dilated venules in the lamina propria of the anterior wall compared to control subjects (2).

lining that ends at the lamina propria. The muscular layer lies beneath the lamina propria and consists of mostly smooth muscle fibers along with small amounts of a collagen and elastin connective tissue (1). When this muscularis is surgically dissected from the epithelium during a split-thickness anterior colporrhaphy dissection, it is often referred to as “pubocervical fascia” (10). The third layer is known as the adventitia. It is loose areolar tissue and is shared by the bladder. Boreham et al compared specimens taken from the anterior vaginal cuff in both normal subjects and those with prolapse (2). Following immunohistologic review it was noted that women with prolapse had a significantly reduced fraction of smooth muscle, disorganized smooth muscle bundles, and decreased alpha-actin staining in the muscularis as well as dilated venules in the lamina propria of the anterior wall compared to control subjects (2).

FIGURE 28.1 ● Anatomic/histologic layers of vagina and bladder. Both (A) and (B) are full-thickness, cross-sectional anterior vaginal wall specimens. (A) taken at hysterectomy, (B) cadaveric and containing bladder wall. Both show vagina contains squamous epithelium, muscularis (musc), and adventitia (adv). Deep to this is only bladder muscularis and bladder mucosa. No fascia is seen. (From Boreham MK, Wai CY, Miller RT, et al. Morphometric analysis of smooth muscle in the anterior vaginal wall of women with pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;187(1):56-63, Fig. 2, with permission.) |

The International Continence Society defines anterior vaginal wall prolapse as “descent of the anterior vagina so that the urethrovesical junction (a point 3 cm proximal to the external urinary meatus) or any anterior point proximal to this is less than 3 cm above the plane of the hymen” (11). The cause of anterior prolapse, while not fully understood, is clearly multifactorial. Largely, the acute traumatic events—vaginal birth and pelvic surgery —are etiologically coupled with our life-long “slings and arrows” of hard work: raising a family, gaining weight, aging, menopause, and the many problems “flesh is heir to.” Parity and obesity are strongly associated with increased risk for anterior compartment prolapse (8). Neurologic pelvic floor injury and underlying connective tissue disorders have been implicated (12,13). Physical work demands (14) and previous pelvic floor surgery (15) have also been shown to confer increased risk. The Pelvic Organ Support Study (POSST) demonstrated that straining at stool is also associated with anterior vaginal wall descent (16).

The key to anterior vaginal support is an interaction between the pelvic musculature, in which the anterior compartment sits, and the connective tissue attachments, which keep it stabilized. Any damage to either the pelvic muscular lift or the connective tissue stabilization, such as those that occur with parturition, can lead to a pathologic loss of support or destabilization (14,17). This is the excellent “boat in dry dock” analogy (18).

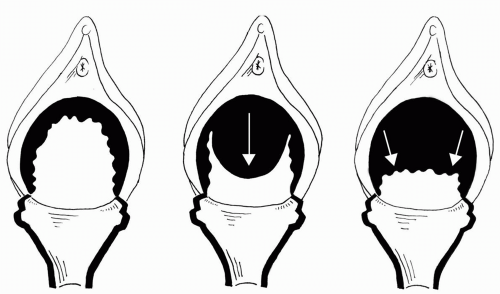

Nichols and Randall (19) describe two distinct types of anterior vaginal prolapse: distention and displacement (Fig. 28.2). These defects may occur individually or together. A distention cystocele is the result of attenuation of the midline anterior vaginal wall, usually secondary to overdistention at vaginal delivery. A Nichols distention cystocele is basically equivalent to a Richardson central defect. It may remain asymptomatic until menopause, when estrogen-related elastic tissue and smooth muscle are lost. The vaginal walls in these patients appear thin, with a loss of rugal folds. Since the epithelium is separated from the muscularis, it is stretched and the rugae are lost as the epithelium becomes smooth. The displacement cystocele is the other major type. It results from tearing of lateral vaginal fibroelastic cells from one or both arcus tendineii, either apically or completely (20). This is also known as a paravaginal defect (PVD). Pure PVD will spare rugae.

George White was first to describe the PVD and its vaginal repair from 1909 to 1911 (8,21). A. Cullen Richardson in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s (22) and then John DeLancey in the 1980s to the present (4) have advanced our understanding of female pelvic floor anatomy. Through their cadaver work we have learned the integral importance of

the ATFP (white line) and lateral attachments along with the arcus tendineus levator ani in anterior vaginal support. They have taught us well the lesson that we must carefully observe the anterior lateral sulci, in our clinic and operating rooms, given the limitations of each examination, regardless of Valsalva effort and with as much uprightness as possible, so as to not miss the PVD, complete or apical, unilateral or bilateral, when present.

the ATFP (white line) and lateral attachments along with the arcus tendineus levator ani in anterior vaginal support. They have taught us well the lesson that we must carefully observe the anterior lateral sulci, in our clinic and operating rooms, given the limitations of each examination, regardless of Valsalva effort and with as much uprightness as possible, so as to not miss the PVD, complete or apical, unilateral or bilateral, when present.

FIGURE 28.2 ● Two types of cystocele. (A) Well-supported: all areas of support are intact. (B) Distention: midline or central loss of support. (C) Displacement: lateral or paravaginal separation. |

Richardson et al described a transverse defect (TD) occurring as a result of separation of the anterior compartment muscular/connective tissue from its attachment to the pericervical ring of fibromuscular tissue as well as from the cardinal and uterosacral ligament complex. This defect results in a large cystocele with a bladder neck that is otherwise well supported (20).

The least common defect of anterior vaginal wall support is the distal defect, in which the distal portion of the urethra is separated from its attachment at the urogenital diaphragm/perineal membrane near the symphysis pubis. This defect is evident as an outward projection of the external urethral meatus (20).

EVALUATION

History

It is essential to quality care that the physician carefully evaluate all aspects of pelvic support and whether or not a patient has coexisting defects or problems such as urinary incontinence. Many patients who present with anterior vaginal prolapse will complain of symptoms directly associated with the protrusion of the vaginal wall as well as symptoms of voiding difficulty or urinary incontinence (22,23). Symptoms directly related to the prolapse include pelvic pressure, sensation of a vaginal bulge, vaginal fullness, low back pain, difficulty sitting, spotting, and dyspareunia. Urinary symptoms such as voiding difficulty or stress urinary incontinence commonly occur in patients with anterior vaginal prolapse (24). Many women report the need to manipulate the prolapse or use abdominal or vaginal pressure in order to facilitate voiding. Often patients report a feeling of incomplete emptying of the bladder. As the prolapse advances, many women with prior urinary incontinence will report an improvement of this condition. This is due to a kinking-type mechanism between the urethra and the advancing anterior vagina, which results in an obstruction to normal urinary flow (23). This condition could place the patient at greater risk for urinary tract infections.

Other important medical considerations include the presence of urinary urgency or frequency and past history of significant diseases, surgeries, medications, and allergies. If the patient has undergone prior pelvic operations, particularly for incontinence or prolapse, we find it very important to review these operative notes. There are sometimes important technical lessons to be learned from them, and this is preferable to learning them intraoperatively. Occasionally, such notes may guide the surgeon to alter the surgical recommendation. At the very least, the operative details, if thoroughly dictated, will add preincision knowledge and confidence to the surgical team.

Pelvic Examination

The dynamic pelvic examination for prolapse may be conducted in one or more of three positions. Examining a patient in the lithotomy position is most often used. However, a seated upright position with the same forceful, repeated Valsalva bearing-down efforts might contribute high-quality observations while maximizing prolapse findings. Initially, a visual inspection of the external genitalia is performed. The examiner should describe any exteriorized bulge or abnormality. Atrophy, including labial agglutination, pallor, dystrophic changes, or local lesions should be noted. The patient is then asked to bear down while the examiner gently parts the labia. One may note any defects without using the potentially artifact-producing speculum. Should the examiner still have difficulty in confirming the total extent of a prolapse, the patient may be examined in the standing position with either leg elevated by a single step. This enables the examiner to define the full extent of prolapse and its components. A gentle rectovaginal examination, with the thumb in the posterior vaginal fornix and the index finger in the rectal ampulla, before and during Valsalva effort, is a good diagnostic examination for enterocele.

The warmed, moistened posterior blade of a Graves or Pedersen speculum or a Sims retractor is placed, according to vaginal size, to gently depress the posterior aspect of the vagina. This allows the examiner an optimal view of the anterior vaginal wall. After this initial visual examination is complete, the patient is asked to bear down forcefully with her lungs full or to cough. The examiner notes extent and place of descent. When examining the anterior wall for prolapse, one must not only perform Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ; 25) measurements for prolapse severity, but also assign specific sites of defect (i.e., central/midline, PVD, TD). While observing anterior descent during Valsalva effort, one ought to pay particular attention to the area of the urethrovesical crease. It is quite common in patients with anterior pelvic organ prolapse to note rotational descent of the bladder neck. This finding will usually predict a positive cotton swab test for urethral hypermobility. Careful attention is paid to the presence or absence of rugal folds, as well as noting whether or not there is a loss of the lateral sulcus and/or anterior fornix. Other simple tools help answer the important question: “Is this anterior prolapse secondary to a central and/or a PVD?” A separated ring forcep or Baden vaginal wall analyzer is placed into the lateral sulcus and the curve is pointed posteriorly toward the ischial spines; the lateral vagina is returned to the ATFP and the midanterior vaginal tissues are elevated. The patient is once again asked to strain, and if no further prolapse is noted, a defect of the paravaginal type is strongly suspected (26). Should the midanterior wall continue to descend on strain despite instrumental elevation, the patient is likely to have a central defect. A PVD, however, is not ruled out.

The examiner is then able to grade the severity of any defects with the POPQ or Baden-Walker (27) systems. The POPQ, being quantitative, allows numerical comparisons between preoperative and postoperative and in studying groups of patients in research. Since its measurements are conducted along a linear axis, the POPQ does not include side-to-side (e.g., PVD) parameters. This and any other findings outside of the POPQ system ought to be noted.

Because of the association of occult stress incontinence with anterior prolapse, it is useful to note if the patient shows urinary incontinence during repetitive cough with the prolapse reduced. A TD is diagnosed by observing the anterior cervical fornix. If the normal forniceal indentation is lost between the base of the anterior cervical lip and the anterior vaginal apex, the patient may be said to have a TD.

Diagnostic Tests

A thorough history and physical examination in the office setting may be all that are necessary in evaluating patients with anterior vaginal prolapse. The physician should obtain a urine sample to rule out infection in any patient with urinary symptoms. If coexisting urinary incontinence is a problem, appropriate urodynamic testing should be completed prior to treatment. If the patient does not currently complain of voiding dysfunction or urinary incontinence yet the anterior prolapse is grade 3 or greater, urethral function (via urodynamic evaluation) should be carefully assessed with the prolapse reduced. This is very important in that women with severe anterior vaginal prolapse may in fact be continent due to urethral kinking (24). Once the prolapse is effectively reduced, occult or latent stress incontinence may be unmasked. Pessaries (28), large cotton swabs (Scopettes), or ring forcep-type instruments can be used in order to reduce anterior prolapse at the time of urodynamic testing. Care should be taken to ensure that the prolapse-reducing device does not occlude the urethra, causing a false-negative cough stress test. If these maneuvers lead to urinary leakage with cough or Valsalva (occult USI), the surgeon may recommend that an appropriate anti-incontinence procedure be performed

at the time of surgical correction for anterior wall prolapse.

at the time of surgical correction for anterior wall prolapse.

SURGICAL REPAIR

The historical suboptimal success and longevity of surgical repairs for anterior compartment prolapse are well described in this often-mentioned but still relevant quote from George White (9): “Ahlfelt states that the only problem in plastic gynecology left unsolved by the gynecologist of the past century is that of permanent cure of cystocele.” Ahlfelt is describing 19th-century results. White was active in the early 20th century, trying to find a more effective cure at the arcus tendineii. As the 21st century begins, some studies are showing an improved long-term cure rate of this most common site for pelvic floor prolapse, the anterior compartment. Table 28.1 shows surgical outcomes studies since 1989, all but one demonstrating acceptable success rates for anterior compartment prolapse repair (29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree