Anorectal Disease

Kelli M. Bullard

Daniel A. Saltzman

Todd M. Tuttle

Lucas Boyd is a 47-year-old man who seeks medical attention for a 10-day complaint of progressive rectal pain, perianal swelling, and foul-smelling drainage. He complains of a constant ache that is exacerbated by sitting and walking. He denies having fever, chills, constipation, diarrhea, or abdominal pain. His medical history is unremarkable, he takes no medications, and he has no allergies. Mr. Boyd’s vital signs are normal, and his temperature is 37°C. Examination of the perianal region reveals a fluctuant tender mass measuring 3 × 2 cm in the left perianal region. The overlying skin is indurated and erythematous. He is too tender to tolerate a digital rectal examination (DRE). Significant laboratory data include a hemoglobin level of 13.2 g per dL, a white blood cell count of 7,000, and a normal platelet count.

What is the most likely diagnosis for Mr. Boyd’s complaint on the basis of the history and physical examination?

Where do perirectal abscesses originate?

View Answer

The majority of perirectal abscesses result from infections of the anal glands and crypts (cryptoglandular infection). The glands are found in the intersphincteric plane, traverse the internal sphincter, and empty into the anal crypts at the level of the dentate line. Infection of an anal gland results in the formation of an abscess that enlarges and spreads along one of several planes in the perianal and perirectal spaces. More unusual causes of perirectal abscess (especially recurrent abscess and fistula) include Crohn’s disease, malignancy, radiation, and opportunistic infection.

What is the anatomy of the anal canal?

View Answer

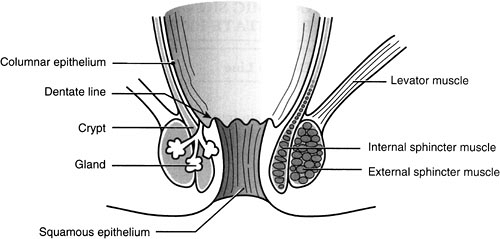

A basic knowledge of anorectal anatomy is fundamental to understanding perirectal disease (Fig. 15.1). The anal canal, the terminal end of the alimentary tract, measures approximately 2 to 4 cm (2 to 3 cm in most women, 3 to 4 cm in most men). In the anal canal, the internal sphincter is the continuation of the inner circular smooth muscular layer of the rectum and the external sphincter is the continuation of the outer longitudinal skeletal muscular layer of the rectum. The superior border of the external sphincter fuses with the puborectalis muscle and forms a sling originating at the pubis and joining behind the rectum. The intersphincteric plane, the space between the internal and external sphincters, is a fibrous continuation of the longitudinal smooth muscle of the rectum. Normally, 6 to 10 anal glands lie in this intersphincteric space.

What is the dentate line, and what is its anatomic significance?

View Answer

The dentate line is an important surgical landmark at the union of the embryonic ectoderm with the gut endoderm. The line is recognizable as the line demarcating the transitional and squamous epithelium below and the rectal mucosa above. The columns of Morgagni begin at this line and extend cephalad. The dentate line divides the nervous system, vascular supply, and lymphatic drainage of the anal canal into two routes (Table 15.1).

TABLE 15.1. Anatomic Significance of the Dentate Line | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

What is the typical presentation of a perirectal abscess?

View Answer

Severe anal pain is the most common presenting complaint. Walking, coughing, or straining can aggravate the pain. A palpable mass is often detected by inspection of the perianal area or by DRE. In the absence of systemic sepsis, fever and leukocytosis are rare. The diagnosis of a perianal or perirectal abscess usually can be made with physical examination alone (either in the office or in the operating room); however, complex or atypical presentations may require imaging studies such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging to fully delineate the anatomy of the abscess. Rarely, patients will present with fever, urinary retention, and signs of sepsis. These findings should raise the suspicion of a severe, necrotizing soft tissue infection (often called Fournier’s gangrene), which can be life threatening.

How does the original infection of the anal glands spread?

View Answer

As infection in an anal gland enlarges, the resulting abscess spreads in one of several directions:

Perianal abscess: most common; appears as a painful swelling at the anal verge, resulting from the spread of pus downward between the two sphincters.

Intersphincteric abscesses: occur in the intersphincteric space and can be notoriously difficult to diagnose, often requiring an examination under anesthesia.

Ischiorectal abscess: forms if the growing intersphincteric abscess penetrates the external sphincter below the puborectalis. Infection can spread into the fat of the ischiorectal fossa, and the abscess can become quite large. An ischiorectal abscess may involve both sides of the ischiorectal fossa, forming a horseshoe abscess. DRE will reveal a painful swelling laterally in one or both ischiorectal fossae.

Supralevator abscess: uncommon; may result from extension of an intersphincteric or ischiorectal abscess upward or extension of an intraperitoneal abscess downward.

What is the differential diagnosis of a perirectal inflammatory process?

View Answer

The differential diagnosis includes pilonidal abscess, hidradenitis suppurativa, infected sebaceous cyst, folliculitis, periprostatic abscess, Bartholin abscess, inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease), or unusual infection (e.g., actinomycosis, tuberculosis).

Mr. Boyd is admitted to the hospital and taken to the operating room for incision and drainage of the abscess. Creating a small incision parallel to the anus drains the abscess. Anoscopy is performed and no internal opening (i.e., infected gland) is found. Mr. Boyd’s postoperative care includes sitz baths and analgesia. He is discharged the day after surgery.

What is appropriate treatment for a perirectal abscess?

View Answer

Perianal and perirectal abscesses should be treated by surgical drainage as soon as the diagnosis is established. If the diagnosis is in question, an examination under anesthesia is often the most expeditious way to both confirm the diagnosis and treat the problem. Delayed or inadequate treatment may occasionally cause progression to serious, life-threatening infection.

The site of the surgical incision depends on the location of the abscess:

A perianal abscess is best drained through a small incision parallel to the anal verge to avoid injury to the sphincter, which could occur with a radial incision.

An ischiorectal abscess is drained in a similar fashion, but may require a larger incision.

An intersphincteric abscess is drained into the anal canal by creating a limited sphincterotomy.

A supralevator abscess can be extremely complex and drainage depends on the origin of the abscess:

If the abscess is secondary to an upward extension of an intersphincteric abscess, it should be drained through the rectum.

If a supralevator abscess arises from the upward extension of an ischiorectal abscess, it should be drained through the ischiorectal fossa.

If the abscess is secondary to intraabdominal disease, the primary process requires treatment and the abscess is drained via the most direct route (i.e., transabdominally, rectally, or through the ischiorectal fossa).

Postoperatively, sitz baths and analgesia are the mainstay of treatment. Packing is rarely required and can increase pain. Stool softeners and bulk agents (fiber) can be helpful. Treatment of a perianal or perirectal abscess by drainage alone cures about 50% of patients. The remaining 50% develop persistent fistulas in ano (1).

Although often administered for the treatment of perirectal abscesses, antibiotics are only indicated if there is extensive overlying cellulitis or if the patient is immunocompromised, has diabetes mellitus, or has valvular heart disease. Antibiotics alone are ineffective in treating perianal or perirectal infection.

Mr. Boyd’s recovery is uneventful, but 6 months later he returns with a complaint of persistent perirectal drainage. Physical examination reveals left perianal induration and an external opening at the site of the prior incision that is draining pus.

What is a fistula in ano?

View Answer

A fistula is an abnormal communication between two epithelium-lined surfaces. A fistula in ano has its external opening in the perirectal skin and its internal opening in the anal canal at the dentate line. The fistula usually originates in the infected crypt (internal opening) and tracks to the external opening, usually the site of prior drainage.

What are the most common symptoms of fistula in ano?

View Answer

The most common symptom of fistula in ano is persistent drainage. Recurrent abscesses may occur, especially if the external opening heals. Pain is rare with fistula in ano and suggests the presence of an undrained abscess. Patients may also complain of perirectal itching, irritation, and discharge (2).

What is the pathogenesis of fistula in ano?

View Answer

A fistula in ano forms during the chronic phase of an acute inflammatory process that begins in the intersphincteric anal glands. The course of the fistula can often be predicted by the anatomy of the previous abscess. Fistulas are categorized based on their relationship to the anal sphincter complex (3):

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree