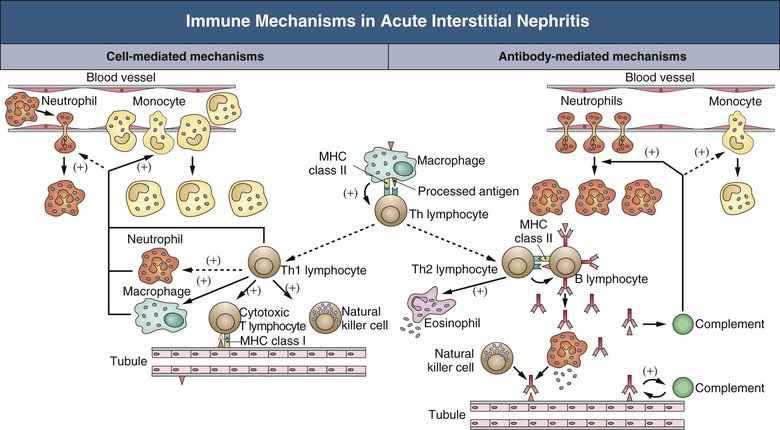

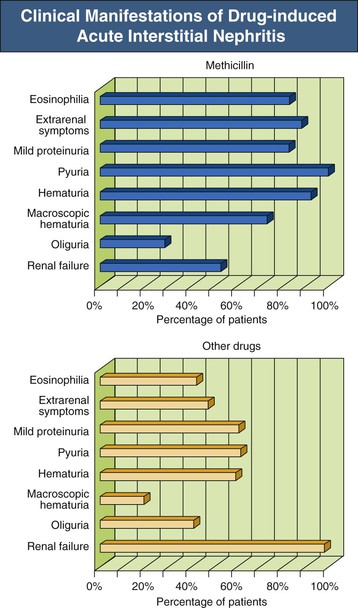

Jerome A. Rossert, Evelyne A. Fischer Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is an acute, often reversible disease characterized by inflammatory infiltrates within the interstitium. AIN is a rare cause of acute kidney injury (AKI), but it should not be overlooked because it usually requires specific therapeutic interventions. Most studies suggest that AIN is an immunologically induced hypersensitivity reaction to an antigen that is classically a drug or an infectious agent. Evidence for a hypersensitivity reaction in drug-induced AIN includes the following: it occurs only in a small percentage of individuals; it is not dose dependent; it is often associated with extrarenal manifestations of hypersensitivity; it recurs after accidental reexposure to the same drug or to a closely related one; and it is sometimes associated with evidence of delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction (renal granulomas). Similarly, AIN secondary to infections can be differentiated from pyelonephritis by the relative absence of neutrophils in the interstitial infiltrates and the failure to isolate the infective agent from the renal parenchyma, again suggesting an immunologic basis to the disease. Studies of experimental models of AIN have shown that three major categories of antigens can induce AIN.1 Antigens may be tubular basement membrane (TBM) components (such as the glycoproteins 3M-1 and TIN-Ag/TIN1), secreted tubular proteins (such as Tamm-Horsfall protein), or nonrenal proteins (such as from immune complexes). Although some types of human AIN may be secondary to an immune reaction directed against a renal antigen, the majority of cases of AIN are probably induced by extrarenal antigens, being produced in particular by drugs or infectious agents. These antigens may be able to induce AIN by a variety of mechanisms. These mechanisms include binding to kidney structures (“planted antigen”); acting as haptens that modify the immunogenicity of native renal proteins; mimicking renal antigens, resulting in a cross-reactive immune reaction; and precipitating within the interstitium as circulating immune complexes. Studies of experimental models of AIN show that their pathogenesis involves either cell-mediated immunity or antibody-mediated immunity (Fig. 62-1). In humans, most forms of AIN are not associated with antibody deposition, which suggests that cell-mediated immunity plays a major role. This hypothesis is reinforced by the fact that interstitial infiltrates usually contain numerous T cells and that these infiltrates sometimes form granulomas. Nevertheless, deposition of anti-TBM antibodies or of immune complexes can be observed occasionally in renal biopsy specimens, and antibody-mediated immunity may play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease in these cases. Formation of immune complexes within the interstitium, or interstitial infiltration with T cells, will result in an inflammatory reaction. This reaction is triggered by many events, including activation of the complement cascade by antibodies and release of inflammatory cytokines by T lymphocytes and phagocytes (see Fig. 62-1). Although the interstitial inflammatory reaction may resolve without sequelae, it sometimes induces interstitial fibroblast proliferation and extracellular matrix synthesis, leading to interstitial fibrosis and chronic renal failure. Cytokines such as transforming growth factor β appear to play a key role in the latter process. Acute interstitial nephritis is an uncommon cause of AKI and is identified in only about 2% to 3% of all renal biopsy specimens, although this proportion could be increasing.2 However, it may account for up to 10% to 25% of patients undergoing renal biopsy for unexplained or drug-induced AKI, respectively.2 Although AIN can occur at any age, it appears to be rare in children. Before antibiotics were available, AIN was most commonly associated with infections, such as scarlet fever and diphtheria. Currently, AIN is most often induced by drugs, particularly antimicrobial agents, proton pump inhibitors, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Drug-induced AIN appears to account for about 75% to 90% of all cases. In the 1960s and 1970s, most cases of drug-induced AIN were caused by methicillin, and the clinical manifestations of methicillin-induced AIN were considered the prototypical presentation of AIN. Since then, many other drugs have been implicated in the induction of AIN (Box 62-1), of which antimicrobial agents (in particular, β-lactam antibiotics, sulfonamides, fluoroquinolones, and rifampin) and NSAIDs (especially fenoprofen) as well as cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors have been most commonly involved. Antiulcer agents, diuretics, phenindione, phenytoin, and allopurinol have also been reported to cause AIN. There are increasing numbers of reports of AIN induced by proton pump inhibitors, with more than 70 reported biopsy-proven cases.3 Recently, cases of drug-induced AIN have also been reported in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected patients treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)4 and in cancer patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors.5 Most other drugs have only rarely been linked with AIN (see Box 62-1). The clinical characteristics of drug-induced AIN are now recognized as much more varied and nonspecific than the spectrum seen in classic methicillin-induced AIN (Fig. 62-2).2,6,7

Acute Interstitial Nephritis

Definition

Pathogenesis

Epidemiology

Drug-Induced Acute Interstitial Nephritis

Clinical Manifestations

Renal Manifestations

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Acute Interstitial Nephritis

Chapter 62