Jeffrey S. Palmer, MD, FACS, FAAP

The normal anatomy of the penis includes the prepuce (foreskin), glans, urethral meatus, coronal sulcus, and penile shaft. The ventral surface of the penile shaft has the median raphe that is contiguous with the scrotal raphe. Anomalies of the penis and scrotum are common and may be congenital, acquired, or iatrogenic. The congenital anomalies may result from a disorder of sexual differentiation, genital differentiation, or genital growth and may be associated with other syndromes (Table 131–1) or organ systems. For example, up to 50% of children with congenital anorectal malformations also have an associated urologic malformation.

Table 131–1 Male Genital Anomalies That Commonly Occur in Various Syndromes (Microphallus, Hypospadias, Ambiguous Genitalia, and Bifid Scrotum)

| ANOMALY | FEATURES |

|---|---|

| Anencephaly | |

| Aniridia–Wilms tumor association | WAGR syndrome: Wilms tumor, Aniridia, Genitourinary abnormalities or gonadoblastoma, and mental Retardation |

| Bladder exstrophy | |

| Börjeson-Forssman-Lehman syndrome | Microcephaly, mental retardation, large ears |

| Carpenter syndrome | Acrocephaly, polydactyly and syndactyly of feet, congenital heart disease |

| CHARGE association | Coloboma, Heart malformation, Atresia choanae, Retarded growth and development, Genital anomalies, Ear anomalies and/or deafness |

| Cloacal syndrome | |

| Fraser syndrome | Cryptophthalmos, mental retardation, ear anomalies |

| Johanson-Blizzard syndrome | Hypoplastic alae nasi, hypothyroidism, mental retardation, pancreatic insufficiency, deafness |

| Meckel-Gruber syndrome | Occipital encephalomeningocele, micrognathia, polydactyly, cystic renal dysplasia |

| Noonan syndrome | Webbed neck, pectus excavatum, pulmonic stenosis, short stature |

| Opitz syndrome | Hypertelorism, hypospadias, mild to moderate mental retardation |

| Pallister-Hall syndrome | Hypothalamic hamartoblastoma, hypopituitarism, imperforate anus |

| Popliteal pterygium syndrome | Popliteal web, cleft palate, lower lip pits |

| Prader-Willi syndrome | Hypotonia, obesity, small hands and feet, mild to moderate mental retardation |

| Rapp-Hodgkin ectodermal dysplasia syndrome | Hypohidrosis, oral clefts, dysplastic nails |

| Rieger syndrome | Iris dysplasia, hypodontia |

| Robinow syndrome | “Fetal face syndrome”; flat facial profile, hypertelorism, short forearms, thoracic hemivertebrae |

| Schinzel-Giedion syndrome | Growth deficiency, mental retardation, widely patent fontanelles, short forearms and legs, renal anomalies |

| Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome | Ptosis of eyelids, syndactyly of second and third toes, microcephaly, failure to thrive with short stature, mental retardation |

| Triploidy syndrome | |

| Trisomy 4p, 9p, 18, 20p, 21, 22, 9p, 10q, 11p, or 15q deficiency | |

| XXY, XXXXY |

From Jones KL. Smith’s recognizable patterns of human malformation. 5th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1997.

Although ultrasonographic technology has evolved in the past decade permitting earlier fetal sex determination (Efrat et al, 2006), it is inaccurate and is not recommended before 12 weeks of gestation (Odeh et al, 2009). However, prenatal ultrasonography is accurate in sex determination in 99% to 100% of cases after 13 weeks of gestation without malformed external genitalia (Odeh et al, 2009) (Fig. 131–1). In-utero ultrasonography has identified abnormal male genitalia including ambiguous genitalia and penoscrotal transposition (Cheikhelard et al, 2000; Vijayaraghavan et al, 2002; Pinette et al, 2003). More recent ultrasonographic technology, including three-dimensional ultrasonography, is being used to evaluate the fetal external genitalia but there are no definitive results suggesting this as an enhanced diagnostic modality (Verweerd-Dikkeboom et al, 2008; Abu-Rustum et al, 2009).

The understanding of the normal anatomy and embryologic development of the male external genitalia is essential to recognizing and treating penile and scrotal anomalies. Most genital abnormalities noted in neonates do not result in an ambiguous appearance but rather more common conditions such as inconspicuous penis or abnormal penile orientation. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Genetics and Sections on Endocrinology and Urology (2000) published a guide to the normal embryology of the external genitalia and the altered embryology, evaluation, and management of ambiguous genitalia.

Normal Male External Genitalia

Embryology

Normal embryogenesis of the male genitalia involves the formation of the penis and scrotum. The early development of the external genitalia in the two sexes is similar before the 9th week of gestation (Ammini et al, 1997). Understanding factors and sequential steps in normal embryogenesis is fundamental in the comprehension of the pathogenesis of male genital anomalies. These factors include testosterone synthesis by the fetal testis and its enzymatic conversion into dihydrotestosterone by 5α-reductase and the presence of androgen receptors able to recognize the androgenic hormones. The influence of dihydrotestosterone on the androgen receptors results in the differentiation of the genital tubercle, genital (labioscrotal) folds, and genital swelling between 9 and 13 weeks of gestation into the male structures of the glans penis, penile shaft, and scrotum, respectively.

The male develops in a proximal to distal manner. As the penis forms from the elongation and enlargement of the phallus, the lateral walls of the urethral groove form from the ventrally located genital folds. The genital folds then fuse in the midline. The glanular urethra forms from the ingrowth of surface epithelium, but this long-held theory has been challenged with evidence suggesting that it is due to the fusion of the urethral plate (Glenister, 1921; Ammini et al, 1997). The scrotum forms through the inferomedial migration and midline fusion of the genital folds as delineated by the scrotal raphe. In females and in males with abnormalities in testosterone and/or dihydrotestosterone production, 5α-reductase deficiency, or androgen receptor insufficiency, the genital tubercle, genital folds, and genital swellings passively become the clitoris, labia minora, and labia majora, respectively.

Penile Length and Tanner Classification

Penile length significantly increases with gestational age (6 mm at 16 weeks to 26.4 mm at 38 weeks) (Johnson and Maxwell, 2000; Zalel et al, 2001) and during the first 3 months of life. The latter growth is a result of an increase in Leydig cell production of testosterone owing to the loss of the inhibitory effect of maternal estrogens on the fetal pituitary at birth, thereby causing a surge in gonadotropins. During the rest of childhood, penile length increases more slowly until adolescence when the length extensively increases again until the final size is reached. The normal penile size in a full-term male neonate is 3.5 ± 0.7 cm in the stretched length and 1.1 ± 0.2 cm in diameter compared with 13.3 ± 1.6 cm at adulthood. The penile stretched lengths from birth to adulthood are listed in Table 131–2.

Table 131–2 Stretched Penile Length (cm) in Normal Male Subjects

| AGE | MEAN ± SD | MEAN − 2.5 SD |

|---|---|---|

| Neonate, 30-wk gestation | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 1.5 |

| Neonate, 34-wk gestation | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 2.0 |

| 0-5 mo | 3.9 ± 0.8 | 1.9 |

| 6-12 mo | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 2.3 |

| 1-2 yr | 4.7 ± 0.8 | 2.6 |

| 2-3 yr | 5.1 ± 0.9 | 2.9 |

| 3-4 yr | 5.5 ± 0.9 | 3.3 |

| 4-5 yr | 5.7 ± 0.9 | 3.5 |

| 5-6 yr | 6.0 ± 0.9 | 3.8 |

| 6-7 yr | 6.1 ± 0.9 | 3.9 |

| 7-8 yr | 6.2 ± 1.0 | 3.7 |

| 8-9 yr | 6.3 ± 1.0 | 3.8 |

| 9-10 yr | 6.3 ± 1.0 | 3.8 |

| 10-11 yr | 6.4 ± 1.1 | 3.7 |

| Adult | 13.3 ± 1.6 | 9.3 |

Data from Feldman KW, Smith DW. Fetal phallic growth and penile standards for newborn male infants. J Pediatr 1975;86:895; Schonfeld WA, Beebe GW. Normal growth and variation in the male genitalia from birth to maturity. J Urol 1987;30:554; and Tuladhar R, Davis PG, Batch J, Doyle LW. Establishment of a normal range of penile length in preterm infants. J Paediatr Child Health 1998;34:471.

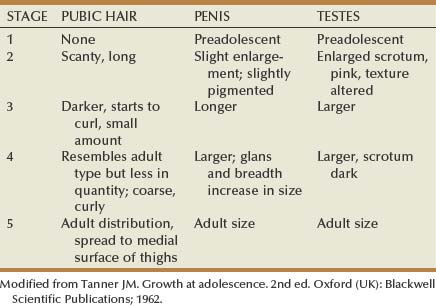

Tanner stages are a set of recognizable changes that occur to pubic hair, penis, and testes during puberty that are helpful in evaluating patients (Table 131–3). The stages range from preadolescent penis and testes with no pubic hair (stage 1) to adult-size penis and scrotum with adult pubic hair distribution (stage 5).

Penile Anomalies

Prepuce (Foreskin)

Phimosis and Paraphimosis

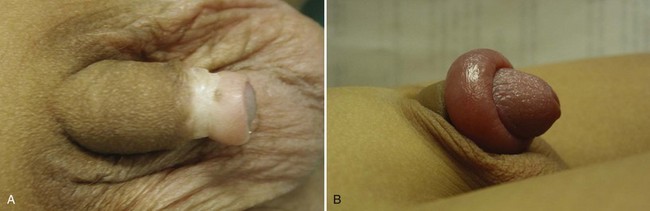

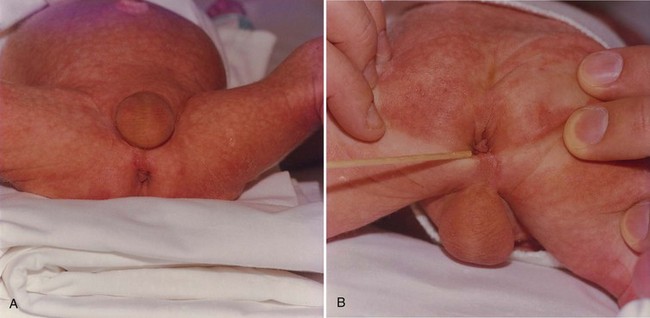

At birth, a physiologic phimosis (Fig. 131–2A) with either partial or complete inability to retract the prepuce exists owing to natural adhesions between the glans and inner preputial skin and/or due to a preputial ring. Two factors are involved in the separation of the prepuce from the glans: (1) epithelial debris, referred to as smegma, accumulates during the first 3 to 4 years of age under the prepuce, and (2) intermittent penile erections. Preputial retractability increases with age, with 90% of uncircumcised boys 3 years of age with completely retractable prepuces and less than 1% by 17 years of age with phimosis (Oster, 1968; Kayaba et al, 1996). Therefore, primary phimosis is almost always resolvable during childhood without intervention. Secondary phimosis can result from several causes, including forceful retraction and balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO). Forceful preputial retraction is usually not recommended because it can result in a cicatrix of the prepuce.

Penile problems associated with the uncircumcised penis include paraphimosis, infection, urinary tract infection (UTI), and cancer. Paraphimosis (Fig. 131–2B), the entrapment of the prepuce behind the glans penis, can result in gangrene if not reduced in a timely fashion by manipulation, dorsal slit procedure, or circumcision. Severe edema of the foreskin occurs within several hours, depending on the tightness of the tip of the foreskin, and makes reduction more difficult. In most cases, manual compression of the glans with placement of distal traction on the edematous foreskin allows reduction of the paraphimotic ring. Other treatments include application of an iced glove for 5 minutes, application of granulated sugar for 1 to 2 hours, and placement of multiple punctures in the edematous skin (Mackway-Jones and Teece, 2004).

Indications to enhance preputial retractability include persistent primary phimosis, secondary phimosis, balanitis, posthitis (i.e., inflammation of the prepuce), BXO, and UTIs. Several topical corticosteroid creams using different regimens have been successfully used to treat phimosis with a relatively small number of side effects. Palmer and Palmer (2008) compared the efficacy of two different topical betamethasone treatment regimens with respect to outcome and untoward effects. Children were treated twice daily for 30 days (i.e., 60 doses) or three times daily for 21 days (63 doses). There was an 84.5% and 87% response rate, respectively. Only one child had an untoward effect (candidal dermatitis).

Circumcision

Circumcision dates back more than 6000 years ago with the oldest documented evidence thought to date to sixth dynasty (2345-2181 BC) tomb artwork in Egypt. Since that time different religions, countries, and cultures have adopted various views on circumcision (Palmer, 2009a). Many theories have been proposed to the etiology of circumcision, including as a religious sacrifice, rite of passage, aid to hygiene, a way to differentiate cultural groups, and a method to discourage masturbation.

Elective circumcision in the neonate is a controversial topic. In 1989 the AAP concluded, “Newborn circumcision has potential medical benefits and advantages as well as disadvantages and risks. When circumcision is being considered, the benefits and risks should be explained to the parents and informed consent obtained” (AAP Task Force on Circumcision, 1989). More recently, the AAP again updated its policy statement (AAP Task Force on Circumcision, 1999; Lannon et al, 2000). Its position was essentially unchanged, with the exception that it emphasized the importance of local anesthesia for the procedure. The AAP does not endorse routine circumcision.

There are several techniques for neonatal circumcision, including the Gomco clamp, Mogen clamp, and Plastibell device. There should be complete separation of the prepuce from the glans with complete visualization of the meatus and circumferential visualization of the corona to confirm that there are no anomalies, including hypospadias. When neonatal circumcision is performed, local anesthesia is recommended. Available options include the topical application of a cream containing eutectic mixture of local anesthetic (EMLA; lidocaine and prilocaine), a dorsal penile nerve block, and a penile ring block (Hardwick-Smith et al, 1998). Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that a dorsal penile nerve block is more effective than EMLA cream (Howard et al, 1999; Taddio et al, 2000) because prilocaine in the EMLA cream poses a low risk for methemoglobinemia (Couper, 2000). Circumcision can be performed under local anesthesia even in older boys. For example, Jayanthi and colleagues (1999) reported a series of 287 infants aged 3 days to 9 months (20% older than 3 months) who underwent office circumcision with local anesthesia. However, typically older infants and children are circumcised under general anesthesia rather in the office using a free-hand sleeve resection technique.

Circumcision has several potential benefits, including the prevention of penile cancer, UTIs, sexually transmitted diseases including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and phimosis, as well as lessening of the risk of balanitis. Although some have alleged that neonatal circumcision can lead to sexual dysfunction, long-term studies have not supported this view (Fink et al, 2002; Bleustein et al, 2005). Schoen and associates (2006) determined that neonatal circumcision has a cost benefit compared with postneonatal circumcision, including procedure charges and reduction in future health care costs.

Carcinoma of the penis develops almost exclusively in men who are not circumcised at birth. Phimosis is a significant risk factor (Tsen et al, 2001). Schoen and coworkers (2000b) reported that of 89 men in a large health maintenance organization with invasive penile cancer, only 2 (2%) had been circumcised at birth. Furthermore, of 116 men with penile carcinoma in situ, 16 (14%) had had a neonatal circumcision.

Uncircumcised neonates and infants are predisposed to UTIs (Singh-Grewal et al, 2005). In a study of 100 neonates with a UTI, Ginsburg and McCracken (1982) found that only 3 (5%) of the 62 boys who developed a UTI were circumcised. Subsequently, Wiswell and colleagues (1985) studied more than 2500 male infants and found that 41 had symptomatic UTIs; 88% of these infants were uncircumcised. Uncircumcised boys were almost 20 times more likely than circumcised neonates to develop a UTI. Other studies of larger groups of infants have confirmed these reports (Wiswell, 2000; Zorc et al, 2005) and have demonstrated that neonatal circumcision is less costly than treating UTIs in uncircumcised boys (Schoen et al, 2000a). The increased risk seems to affect boys at least through 5 years of age (Craig et al, 1996), and the incidence of epididymitis is reduced (Bennett et al, 1998). The increased risk of UTIs can be attributed to colonization of the prepuce by urinary pathogens (Gunsar et al, 2004; Bonacorsi et al, 2005). It has been calculated that it takes 111 neonatal circumcisions to prevent one UTI (Singh-Grewal et al, 2005). However, Shim and colleagues (2009) evaluated 190 infants with confirmed normal urinary systems and diagnosed with their first febrile UTI. They assessed the incidence of recurrent UTI during the following year and several risk factors, including acute pyelonephritis. In infants with persistent nonretractile prepuces, recurrent UTI developed in 34%, compared with 17.6% of infants with retractile prepuces.

Whether circumcision reduces the risk of sexually transmitted diseases has been controversial. Several recent reports of a large population of men have demonstrated reduced incidence of HIV infection among men, with a protective effect of 60% (Gray et al, 2007; Bailey et al, 2007). However, a recent study compared 922 uncircumcised, HIV-infected, asymptomatic men in whom 474 underwent immediate circumcision with 448 who were not circumcised to evaluate transmission of HIV to HIV-uninfected female partners (Wawer et al, 2009). After 24 months of follow-up, 18% and 12% of women acquired HIV, respectively, thereby demonstrating that circumcision of HIV-infected men did not reduce HIV transmission to female partners. It has been reported that circumcision may reduce the risk of ulceration, bacterial vaginosis, and trichomonas in female partners (Gray et al, 2009).

Several clinical trials of the effect of circumcision on the prevention of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection, and other sexually transmitted diseases (Auvert et al, 2009; Nielson et al, 2009; Tobian et al, 2009) have been done. Tobian and associates (2009) evaluated 5534 HIV-negative, uncircumcised males, with 3393 being HSV-2 seronegative at enrollment. Of the 3393 men, 1684 underwent immediate circumcision while 1709 were not circumcised in order to evaluate HSV-2 and HPV transmission. At 24 months’ follow-up, HSV-2 seroconversion was 7.8% and 10.3%, respectively, whereas prevalence of high-risk (carcinogenic) HPV genotypes was 18.0% and 27.9%, respectively. This study underscores the benefit of circumcision in reducing the incidence of HSV-2 infection and the prevalence of HPV infection.

Circumcision Complications

The risk of complications after circumcision is 0.2% to 5% (Baskin et al, 1996; Christakis et al, 2000; Ben Chaim et al, 2005). Complications can occur immediately or months to years after a circumcision. The most common complication is bleeding, which occurs in 0.1% and is more common in older children. There usually is bleeding from the frenulum or, less frequently, from a large blood vessel on the penile shaft. The bleeding is usually self-limiting or may require compression. Occasionally cautery with an ophthalmic cautery or silver nitrate stick or a suture may be necessary. Wound infection is another complication, but it is rare and antibiotic ointment (e.g., bacitracin) use after circumcision usually prevents this from occurring. Also, penile degloving due to excess amount of skin removed or the edges of the penile skin not adhering to the mucosal collar can occur after circumcision. The penile shaft will usually epithelize, bridging the defect without any intervention other than the use of antibiotic ointment to the denuded region and warm baths to prevent eschar formation. Immediate suturing of the skin edges and skin grafting are not recommended to bridge the gap.

Penile Skin Complications

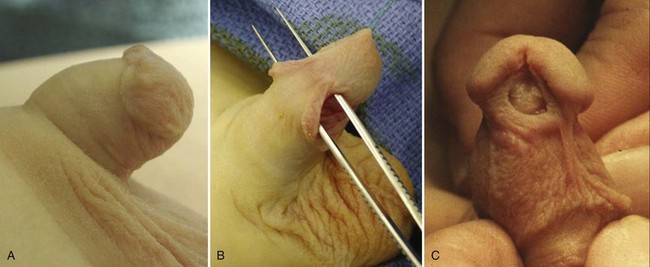

The amount of penile skin excised can also lead to complications after circumcision. Insufficient or asymmetrical prepuce excision can result in a cosmetic and social dilemma for the parents and child, especially as the child gets older (Fig. 131–3A). Unlike neonatal circumcision, circumcision revision requires general anesthesia. Several techniques have been described (Redman, 1995; Brisson et al, 2002; Ching and Palmer, 2008a). Excessive skin excision can result in penile chordee, torsion, and lateral deviation. These conditions, if necessary to repair, may require penile skin flaps or Z-plasty for closure. Excessive skin removal can also result in a trapped penis from a cicatricial scar. The trapped penis can be managed with betamethasone (Palmer et al, 2005), vertical relaxation incision, and formal repair. The use of 0.05% betamethasone in conjunction with manual retraction in children with a trapped penis due to a dense cicatrix of the residual foreskin distal to the glans has a 79% success in softening of the cicatrix with easy exposure of the glans or mild persistence of the cicatrix amenable to vertical relaxation incision (Palmer et al, 2005). Surgical correction includes excision of the cicatrix with possible need for penile skin flaps or Z-plasty for closure.

Glanular Adhesions and Skin Bridges

Glanular adhesions and skin bridges, attachments of the glans and penile shaft, are also common complications associated with circumcision and are usually noticed by the caregiver or primary medical provider. Both can occur in the well-circumcised penis and are usually the result of the physiologic retraction of the penis due to a suprapubic fat pad and diaper irritation of the penis. Glanular adhesions are attachments between the inner prepuce or circumcision incision line attaching to the glans with an incidence decreasing with age owing to epithelial separation of the adhesions (71% of infants, 28% of 1- to 5-year-olds, 8% of 1- to 9-year olds, and 2% of children older than age 9 years) (Van Howe, 1997; Ponsky et al, 2000). Persistent adhesions can be lysed in the office with the application of topical analgesia such as EMLA cream and Pain Ease (Gebauer Company; 1,1,1,3,3-pentafluoropropane, 1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane) (Palmer, 2009b). Use of low-dose corticosteroids has been relatively unsuccessful in lysing adhesions. Skin bridges (Fig. 131–3B) are epithelized adhesions that can lead to penile chordee and torsion, which can be excised in the office with the application of analgesia (Palmer, 2009b) or in the operating room with the use of general anesthesia and may require suturing of the glanular and shaft defects.

Meatal Stenosis

Meatal stenosis is a condition that occurs in children almost only after circumcision during infancy (Fig. 131–4A). It can be congenital, which occurs primarily in neonates with hypospadias, or acquired. The normal urethral meatus is 10 French before 4 years of age, 12 French from 4 to 10 years of age, and 14 French after 10 years of age (Litvak et al, 1976); this can be calibrated with a bougie à boule or sound. There are several proposed causes of secondary meatal stenosis. One theory is that after disruption of the normal adhesions between the prepuce and glans and removal of the foreskin a significant inflammatory reaction occurs, resulting in a severe meatal inflammation and cicatrix formation. Other theories are frenular devascularization or chronic meatitis from diaper irritation of the exposed, unprotected meatus (Persad et al, 1995; Hensle, 1996). BXO is another cause of meatal stenosis (see later). A relatively small percentage of children will develop symptomatic meatal stenosis after neonatal circumcision. Symptoms include (1) typical urinary stream deviation in an upward direction resulting from a meatal baffle (Fig. 131–4B) or ventral web located at the inferior of the meatus, (2) a narrow, high-velocity stream, and (3) penile pain at the initiation of micturition. Urinary tract imaging usually does not reveal any obstructive changes in the urinary tract without other urologic issues but may be indicated for associated UTI or urinary incontinence. Meatotomy or meatoplasty to treat secondary meatal stenosis can be performed in the office with the use of topical lidocaine and prilocaine (EMLA) (Cartwright et al, 1996) or under general anesthesia by making a ventral incision long enough to create a normal meatal caliber. The suturing of the urethral mucosa to the glans with fine, rapidly absorbable sutures tends to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Penile Trauma

The most serious complications associated with circumcision are penile trauma, including urethral injury, excision of the glans and/or penile shaft, and penile necrosis (see Fig. 131–3C). Urethral injury requires a urethroplasty with the technique dependent on the severity of the excision. Excision of the glans can be repaired by suturing the excised tissue back to the penis without usually requiring the need for microscopic repair (Sherman et al, 1996) and with usually good results if performed within 8 hours. Penile necrosis can result from thermal injury due to several causes, including cautery contacting the metal ring applied to the prepuce being excised or the inappropriate use of lasers to perform a circumcision. Several options are available without ideal outcomes, including penile reconstruction and female gender reassignment with bilateral orchiectomy (Gearhart and Rock, 1989; Bradley et al, 1998). Although the cosmetic and functional results of phallic reconstruction have advanced, they are still being refined (De Castro et al, 2007; Hoebeke et al, 2009). The issues with gender reassignment can include these children growing up with a male identity believed to result from in-utero and neonatal androgen imprinting (Reiner, 1996; Diamond and Sigmundson, 1997; Diamond, 1999).

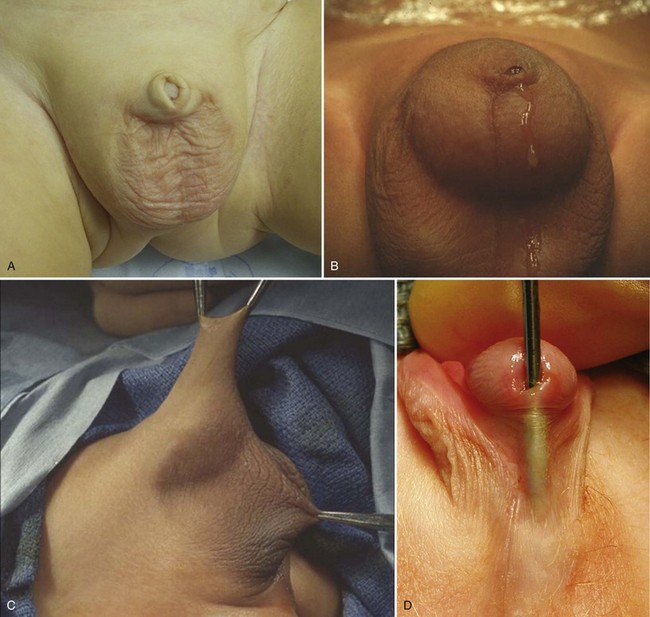

Balanitis Xerotica Obliterans

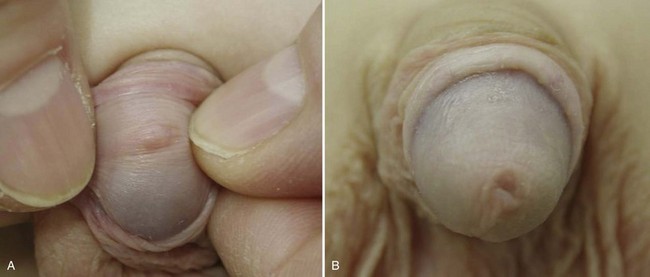

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, or BXO, is a chronic infiltrative and cicatrizing skin condition resulting in pathologic phimosis (Chalmers et al, 1984) (Fig. 131–5). BXO can also affect the glans and meatus, as well as the urethra. The inability to retract the prepuce is the common presentation at puberty and is rare in children younger than 5 years of age (Oster, 1968). Other presenting symptoms include local infection, irritation, discomfort after micturition, bleeding, and occasionally acute urinary retention or urinary incontinence (Bale et al, 1987). Older patients and those with BXO involving the meatus may have a more severe clinical course (Gargollo et al, 2005). The etiology of BXO has not been determined; there is no identified viral or bacterial cause or familial predisposition. The association of BXO and penile cancer in children is also not established.

Figure 131–5 Balanitis xerotica obliterans of the prepuce (A) and meatus (B).

(Courtesy of Warren Snodgrass, MD.)

Treatment of BXO includes medical and surgical management. The use of topical corticosteroids has had limited benefit to treat mild BXO of the prepuce with minimal scar formation (Vincent and Mackinnon, 2005). Circumcision is the preferred treatment along with meatotomy or meatoplasty if there is meatal involvement. Children with meatal involvement should be observed postoperatively because of the risk of recurrent meatal stenosis.

Key Points: Circumcision Complications

Abnormal Penile Number

Aphallia

Penile agenesis results from failure of development of the genital tubercle (Roth et al, 1981) (Fig. 131–6). The disorder is rare and has an estimated incidence of 1 in 10 to 30 million births. The karyotype almost always is 46,XY, and the usual appearance is that of a well-developed scrotum with descended testes and an absent penile shaft. The anus is usually displaced anteriorly. The urethra often opens at the anal verge adjacent to a small skin tag, or it can open into the rectum. The incidence of stillbirth or neonatal death is approximately one third of cases (Gilbert et al, 1990).

Associated malformations are common and include cryptorchidism, vesicoureteral reflux, horseshoe kidney, renal agenesis, imperforate anus, and musculoskeletal and cardiopulmonary abnormalities (Skoog and Belman, 1989; Evans et al, 1999). The connection between the genitourinary and gastrointestinal tract is variable. Skoog and Belman (1989) reviewed 60 reports of aphallia and found that the more proximal the urethral meatus, the greater the likelihood of neonatal death and the higher the incidence of other anomalies. Sixty percent of patients had a postsphincteric meatus located on a peculiar appendage at the anal verge. This group of patients had the highest survival rate (87%) and the lowest incidence of other anomalies (1.2 per patient). Twenty-eight percent of patients had presphincteric urethral communications (prostatorectal fistula), and there was a 36% neonatal mortality rate. Twelve percent had urethral atresia and a vesicorectal fistula for drainage. This group had the highest incidence of other anomalies and a 100% mortality rate.

Children with this lesion should be evaluated immediately by a multidisciplinary approach. Testing should include a karyotype and other appropriate studies to determine whether there are associated malformations of the urinary tract or other organ systems. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be beneficial in determining the severity of the defect (Lapointe et al, 2001). Prompt gender assignment is important. Some of these patients have a male gender identity despite reconstruction as a female, presumably because of in-utero or postnatal sex steroid imprinting (Reiner, 1996; Diamond and Sigmundson, 1997; Diamond, 1999).

Consequently, the recommendation to perform gender reassignment should be made carefully and only after full evaluation by an ambiguous genitalia assessment team and parental counseling. As a male the patient would potentially be fertile, but currently there is an inability to construct a cosmetically acceptable phallus that would allow normal urinary, sexual, and reproductive function (De Castro et al, 2007; Hoebeke et al, 2009). Gender reassignment involves orchiectomy and feminizing genitoplasty in the neonatal period (Gluer et al, 1998; Bruch et al, 1996). At a later age, construction of a neovagina is necessary. Urinary tract reconstruction with simultaneous construction of an intestinal neovagina through a posterior sagittal and abdominal approach in patients with penile agenesis has been described (Hensle and Dean, 1992; Hendren, 1997).

Diphallia

Duplication of the penis is a rare anomaly with an incidence of 1 in 5 million live births (Hollowell et al, 1977) and has a range of appearances from a small accessory penis to complete duplication (Gyftopoulos et al, 2002). In some cases, each phallus has only one corporeal body and urethra, whereas others seem to be a variant of twinning, with each phallus having two corpora cavernosa and a urethra. The penises are usually unequal in size and lie side by side. Other associated anomalies are common, including hypospadias, bifid scrotum, bladder duplication, renal agenesis or ectopia, and diastasis of the pubic symphysis (Maruyama et al, 1999). Anal and cardiac anomalies are also common. Evaluation should include imaging of the entire urinary tract, including a renal ultrasonogram and voiding cystourethrogram. Ultrasonography and MRI can also be done to assess penile development (Marti-Bonmati et al, 1989; Lapointe et al, 2001). The etiology has not been delineated. Treatment must be individualized with consideration of the associated anomalies with the goal of attaining a satisfactory functional and cosmetic result (Dean and Horton, 1991).

Inconspicuous Penis

An inconspicuous penis refers to a penis that appears to be small with a normal stretched penile length measured from the pubic symphysis to the tip of the glans (see Table 131–2) and normal diameter of the penile shaft (Bergeson et al, 1993). This condition can be congenital or acquired and is usually of great concern for parents. Several entities are included in this disorder, including buried penis, trapped penis, and webbed penis (Palmer and Kogan, 1995). These conditions must be differentiated from micropenis, in which the penis is abnormally small. When an infant has an inconspicuous penis, prompt evaluation is necessary for proper treatment and the family must be informed as to whether the penis is or is not normal. The stretched penile length should be measured from the pubic symphysis to the tip of the glans. In addition, the diameter of the penile shaft may be measured by palpation.

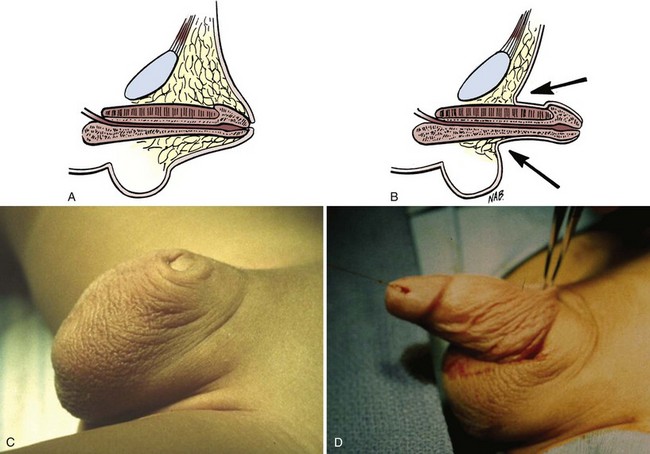

Buried Penis

A buried penis, also referred to as hidden or concealed penis, is a form of inconspicuous penis (Cromie et al, 1998). A buried penis is a normally developed penis that is hidden away by the suprapubic fat pad. This condition can be classified into three categories based on etiology for the concealment (Maizels et al, 1986; Casale et al, 1999): (1) poor penopubic fixation of the skin at the base of the penis, (2) obesity, and (3) a trapped penis from cicatricial scarring after penile surgery, typically a circumcision.

The congenital form of buried penis is believed to be due to the inelasticity of the dartos fascia, which normally allows the penile skin to slide freely on the deep layers of the shaft, with restricted extension of the penis because the penile skin is not anchored to the deep fascia (Fig. 131–7). The acquired form from obesity typically seen in older children and adolescents is due to abundant fat on the abdominal wall hiding the penile shaft. The other acquired form, a trapped penis, results from embedding of the penis in the suprapubic fat pad from scar formation over the glans. This deformity may occur after neonatal circumcision in an infant with significant scrotal swelling due to a hernia or hydrocele or after routine circumcision in an infant with a webbed penis. Also, in some neonates the penile shaft seems to retract naturally into the scrotum; and if circumcision is performed in this situation, the skin at the base of the penis may form a cicatrix over the retracted phallus. This condition should be differentiated from a transient buried penis resulting from a large suprapubic fat pad noted in early childhood that resolves with increased age and ambulation (Eroglu et al, 2009).

Figure 131–7 Buried penis (A and C), which may be visualized by retraction of the skin lateral to the penile shaft (B and D).

On examination, a buried penis must be differentiated from a micropenis, with the latter not having a normal penile stretched length. The clinician should determine whether the glans can be exposed by retracting the skin covering the glans (see Fig. 131–7). If so, it remains the surgeon’s judgment whether correction is warranted. However, if the penis is trapped by physiologic phimosis in the uncircumcised or cicatricial scarring (Fig. 131–8A) in the circumcised penis, this increases the chance of difficulty voiding, maintaining proper hygiene, balanitis, UTIs, and psychosocial issues (Fig. 131–8B) (Kon, 1983).