- All adult patients known or suspected to have cirrhosis require esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to check for the presence of varices.

- All adult cirrhotic patients with medium or large varices, and even those with small varices with red spots or red wale marks, should be prescribed long-term prophylactic treatment with a non-selective beta-blocker to reduce the risk of a variceal bleed. Patients with contraindications to or adverse effects of beta-blockers should be treated with prophylactic endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL).

- Application of screening endoscopy and primary prophylactic therapy for children with portal hypertension should only be undertaken in consultation with a specialist pediatric hepatologist, because relevant studies in children have not yet been undertaken.

- Management of presumed variceal hemorrhage in adults and children requires careful volume replacement and treatment with a vasoactive drug (e.g. octreotide or terlipressin), intravenous third-generation cephalosporins, and a proton pump inhibitor. Urgent upper pan endoscopy is required and optimally if the patient is bleeding at the time of the procedure the patient should be intubated prior to EVL.

- Prevention of repeat variceal bleeding episodes is most successful with a combination of non-selective beta-blocker therapy and follow-up endoscopy with EVL until varices are completely eradicated. Thereafter, non-selective beta-blocker therapy needs to be maintained long term (proven value in adults only).

- Definitive treatment of the cause of portal hypertension should be considered in selected patients (e.g. portosystemic shunt surgery or liver transplantation for those with cirrhosis and in children with portal vein thrombosis, meso-left portal vein bypass surgery should be considered).

- A poor outcome can be predicted in adults by their age older than 60 years, their MELD score more than 18, presence of encephalopathy, or an hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) more than 20 mmHg.

Introduction

Portal hypertension with variceal bleeding is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in both children and adults with liver disease. In children with liver disease due to biliary tract disease, portal hypertension usually manifests early in their clinical course, prior to the onset of hepatic insufficiency. In adults, the predominant cause of portal hypertension is cirrhosis—the etiology being very closely related to geographic region, for example alcohol liver disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL), and hepatitis C in the West and chronic viral hepatitis B or C in the East. As in children, in adults with chronic biliary disease (e.g. primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis) variceal hemorrhage may take place prior to there being overt cirrhosis. It is not unusual for a patient who is bleeding from esophageal and/or gastric varices to have a second pathology, which could also present as hematemesis. Hence the need to fully establish the cause of gastrointestinal bleeding (Box 5.1).

- Esophagitis (often in an immune compromised individual)—may or may not suffer heartburn; esophagitis itself is not a cause of variceal rupture

- Peptic ulcer disease (stomach or duodenum) is not unusual in cirrhotic patients

- Any other cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding

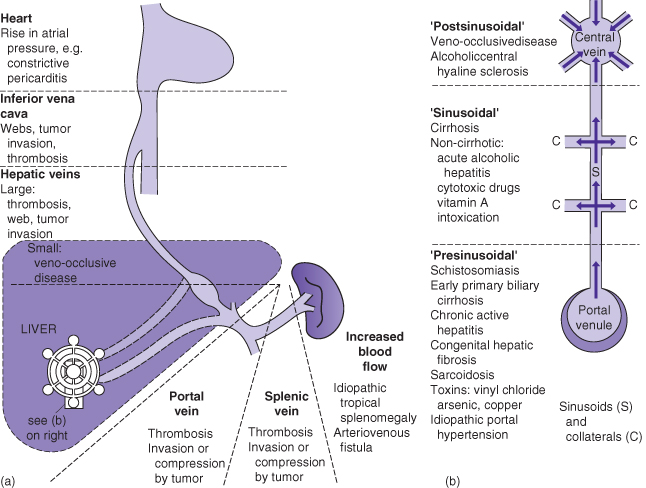

Pathogenesis of Portal Hypertension (Fig. 5.1, Box 5.2)

Non-Cirrhotic Portal Hypertension: Prehepatic, Presinusoidal

This results from an obstruction of the portal venous flow to the liver, most often secondary to a thrombosis in the portal and/or splenic vein. Portal vein thrombosis may also complicate advanced cirrhosis, which may cause retrograde flow and turbulence and thus progressive thrombosis in the portal vein. In children, portal vein thrombosis may occur following umbilical vein catheterization in a sick newborn infant, in whom the clinical presentation is usually with splenomegaly or variceal hemorrhage later in childhood. Prehepatic portal hypertension could also be caused by tumor compression or invasion (e.g. hypernephroma) of the portal vein. An arteriovenous fistula in an individual with Osler–Weber–Rendu syndrome is a rare cause of prehepatic portal hypertension.

- Portal vein thrombosis

- Splenic vein thrombosis

- Splanchnic arteriovenous fistula

- Compression of portal vein by neighboring tumor

- Arteriovenous fistula (Osler–Weber–Rendu syndrome)

- Biliary atresia

- Cystic fibrosis

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Alagille syndrome

- Congenital hepatic fibrosis

- Autoimmune hepatitis

- Chronic hepatitis B and C

- Wilson disease

- α1-antitrypsin deficiency

- Nodular regenerative hyperplasia (commonly mistaken for cirrhosis)

- Portal sclerosis

- Schistosomiasis

- Congenital hepatic fibrosis (e.g. Caroli disease associated with autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease)

- Primary biliary cirrhosis (but without cirrhosis)

- Primary and secondary sclerosing cholangitis (without cirrhosis)

- Myeloproliferative disease/Hodgkin disease

- As for children

- Congenital cardiac disease, inherited hypercoagulable states

- IVC obstruction

- Budd–Chiari syndrome

- Congestive cardiac failure

- Veno-occlusive disease

Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension very rarely causes catastrophic variceal hemorrhage. If this occurs, liver failure is unusual as there is little actual disease of the liver.

Non-Cirrhotic Portal Hypertension: Intrahepatic, Sinusoidal

There are several disease of the liver that predominantly affect the portal tracts, which may cause portal hypertension in the absence of cirrhosis. Most often the damage is secondary to inflammation around the hepatic arteries (e.g. PAN) complicated by thrombosis of the veins within the portal triad. This pathologic process causes nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH). There are many diseases that promote the development of NRH, that is obliteration of the venules in the portal tracts, for example primary biliary cirrhosis, sarcoidosis, schistosomiasis, and certain toxins such as excess vitamin A. Congenital hepatic fibrosis is often misdiagnosed as cirrhosis if the liver biopsy is poorly interpreted, and is caused by obliteration of the terminal branches of the portal vein. Other diseases may damage the entire portal tract, for example myeloproliferative disease and Hodgkin’s disease.

Non-Cirrhotic Portal Hypertension: Posthepatic

Any condition that prevents free flow of venous blood from the liver back to the heart gives rise to posthepatic portal hypertension, as occurs with acute thrombosis of the portal venous radicals (e.g. Budd–Chiari syndrome) for which there are several precipitants, the most common being a congenital disease affecting coagulation. Other slower, even transient, causes are congestive cardiac failure or inferior vena cava obstruction.

Although portal hypertension due to outflow tract obstruction (e.g. Budd–Chiari syndrome) most often presents with marked hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and ascites, it may, albeit rarely, present with variceal hemorrhage and inactive cirrhosis.

Portal Hypertension Due to Cirrhosis of Any Cause

Chronic intrahepatic/sinusoidal disease of any cause may progress to cirrhosis. Under normal conditions, all of the portal venous blood can be recovered from the hepatic veins but in cirrhosis as little as 10% may be recovered; the remainder leaves the liver via collaterals to:

Acute and Chronic Effects of Portal Hypertension Due to Cirrhosis

Hemorrhage

Hemorrhage from esophageal and/or gastric varices may present as the following.

Palpable splenomegaly is usual in all patients with a variceal hemorrhage.

Central Nervous System

Effects of portal hypertension on the central nervous system include the following.

Clinical Features: Rupture of Esophageal/Gastric Varices

Sudden hematemesis results in bright red blood per os and/or melena per rectum (if massive bleed, blood remains bright red). The patient may have no known history of liver disease so there is a need to look for the following.

- Skin stigmata of cirrhosis (spider nevi, palmar erythema, jaundice)—may be present;

- Abdominal examination—abdominal collaterals radiating away from umbilicus;

- Venous hum heard between xiphoid process to umbilicus (Cruveilhier–Baumgarten syndrome)—this is rare;

- Splenomegaly—this is almost universal;

- Liver may be small or large—depending on the etiology of liver disease;

- Liver edge—hard, cirrhosis; soft, suspect extra hepatic portal venous obstruction;

- Ascites—if absent prior to hemorrhage, often develops rapidly following fluid resuscitation if the patient is cirrhotic.

The Course of Investigation and Treatment of Possible Ruptured Esophageal Varices (Box 5.3)

The following steps should be carried out in the investigation and treatment of possible ruptured esophageal varices (Fig. 5.2).

- Assess airway, ventilation, and circulation, and provide general resuscitative support as appropriate.

- Transfuse with blood to maintain hemoglobin at 80–100 g/L. More generous transfusion will increase the likelihood of ongoing bleeding.

- Pantoprazole 80 mg i.v. bolus followed by 8 mg/h i.v. infusion to adults until the source of bleeding is defined. Pantoprazole 2 mg/kg i.v. bolus followed by 0.2 mg/h i.v. infusion to children until the source of bleeding is defined.

- If possible, children with a presumed variceal hemorrhage should be transferred to the nearest center with tertiary pediatric hepatology services as soon as they are stable for transport.

- Commence intravenous infusion of vasoactive drug doses (see Box 5.3).

- Commence intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotic (e.g. third-generation cephalosporin) to treat associated sepsis (often asymptomatic) this maneuver reduces the risk of rebleeding and improves survival.

- An i.v. proton pump inhibitor will facilitate healing of post banding/sclerosis esophageal/gastric ulceration.

- Arrange for urgent EGD once the patient is hemodynamically stabilized (usual target is within 12 h of admission). Procedure should be performed by an endoscopist trained in variceal ligation and interventional endoscopy for management of acute GI bleeding.

- To optimize visibility it is best to perform gastric lavage prior to introduction of the endoscope. If available, introduce a large-bore endoscope with well-functioning suction in place as this optimally demonstrates the site and the source of bleeding.

- If esophageal and/or gastric varices are thought to be the source of bleeding (may be very difficult to determine if patient is hypotensive), banding of the varices at the time of first endoscopy should be performed. Injection sclerotherapy may be considered in adults and older children (typically >15 kg) if banding is not available, but sclerotherapy is associated with more frequent adverse effects. Injection sclerotherapy is the endoscopic management of choice in infants and small children less than 15 kg.

- If rebleeding occurs, a repeat attempt to band or sclerosis should be made, in the meanwhile arrangement for alternate therapy should be sought.

- Adult patients should be admitted to a tertiary referral center if control of variceal bleeding cannot be achieved. Such patients are most often those with advanced cirrhosis (Child’s C). Active management of hypotension will minimize the risk of renal impairment secondary to renal hypoperfusion; particularly in patients with cirrhosis, and regularly monitor renal function. It should however be remembered that over-transfusion many promote further gastrointestinal bleeding, that is keep Hb less than 10 g/L.

- If despite banding or sclerotherapy variceal hemorrhage continues, control of bleeding in the adult patient is most likely to be secured by insertion of a TIPS (transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt) (Fig. 5.3, Plate 5.1), which allows immediate decompression of the portal venous system by the creation of a wide connection between the hepatic vein and a branch of the portal vein but if the radiologist is inexperienced this procedure may be fraught with complications (Box 5.4). Thus TIPS should not be performed unless a trained physician is available.

- When a TIPS is not immediately available, occlusion tubes may be considered for maintenance of hemodynamic stability but only in the short term while planning for further intervention such as TIPS in patients with refractory bleeding. Such tubes include the Linton tube (single gastric balloon), Minnesota or Sengstaken–Blakemore tubes (esophageal and gastric balloons) Fig. 5.4. Their use is associated with significant risk, including esophageal or gastric wall necrosis, ulceration, perforation, and aspiration pneumonia. Therefore, placement of such tubes should only be performed by trained and experienced personnel. If neither insertion of an occlusion tube or TIPS is available then immediate transfer to a referral center with expertise in endoscopic procedures is necessary (Box 5.5), and optimally to a liver transplant center. When access to interventional radiology is unavailable, referral to a surgeon for consideration for a portosystemic shunt should be considered (Fig. 5.5).