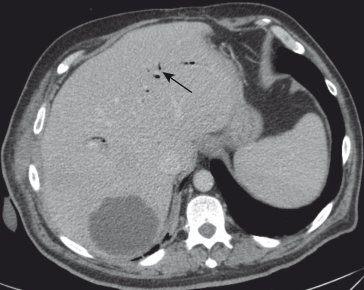

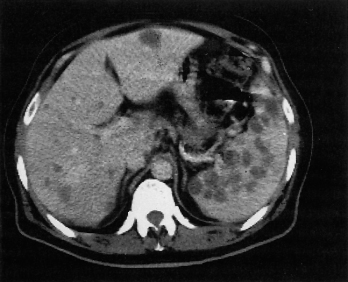

Fig. 32.2. CT scan shows a low attenuation defect in the right lobe of the liver. Note gas in bile ducts (arrow).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows a lesion with sharp borders, hypointense on T1-weighting, and hyperintense on a T2-weighted image. Appearances are not specific or diagnostic of a biliary or haematogenous origin [20].

MR or endoscopic cholangiography may be used to diagnose cholangitic abscesses.

Aspirated material is positive on culture in 70–90% [18]. It should be cultured aerobically, anaerobically and in a carbon dioxide-enriched atmosphere for the Streptococcus milleri group. Organisms in culture-negative pus may be identifiable using 16S PCR and sequencing of the product. Rarely, aseptic abscesses occur in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (usually in association with splenic abscesses) and these appear to be non-infective in origin [21].

Treatment

Management has been revolutionized by the widespread use of imaging, especially ultrasound, allowing localization and easy aspiration for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes (Fig. 32.3). The majority of abscesses can be managed by systemic antibiotics and aspiration, which may need to be repeated [22]. Intravenous antibiotics are rarely effective alone. Drainage is indicated if signs of sepsis persist. Open surgical drainage is rarely indicated [23]. However, solitary left-sided abscess may require surgical drainage, especially in children [24].

Fig. 32.3. Same patient as in Fig. 32.2 after directed puncture and drainage. The abscess is smaller and with antibiotic treatment resolved.

With multiple abscesses, the largest is aspirated and the smaller lesions usually resolve with antibiotics. Occasionally, percutaneous drainage of each is necessary.

Every attempt should be made to make a microbiological diagnosis as this will influence the choice of antimicrobial therapy. Polymicrobial infections may require combination therapy, although antimicrobials such as co-amoxiclav and piperacillin/ tazobactam are often suitable. The increasing incidence of infections caused by resistant Gram-negative organisms means that therapeutic decisions are difficult and these cases should be managed in conjunction with a microbiologist or infectious diseases physician. Therapy is likely to be required for at least 3 weeks. Intravenous therapy for 2 weeks, followed by 4 weeks of oral treatment has been shown to be effective [25,26].

Biliary obstruction must be relieved, usually by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), papillotomy and stone removal. If necessary, a biliary stent is inserted (Chapter 12). Even with eventual cure, fever may continue for 1–2 weeks [18].

The aseptic abscesses discussed above usually respond to corticosteroid therapy, although relapse occurs.

Prognosis

Needle aspiration and antibiotic therapy have lowered the mortality in recent years [16,26]. The prognosis is better for a unilocular abscess in the right lobe where survival is around 90%. The outcome for multiple abscesses, especially if biliary in origin, is very poor. The prognosis is worsened by delay in diagnosis, associated disease, particularly malignancy [27], hyperbilirubinaemia, hypoalbuminaemia, pleural effusion and older age [28].

Hepatic Amoebiasis

Three species of Entamoeba are known to infect humans: E. histolytica, E. dispar and E. moshkovskii [29]. Entamoeba histolytica is responsible for significant invasive disease, whereas E. dispar has a roughly tenfold greater prevalence. The epidemiology and pathogenicity of E. moshkovskii is still poorly understood [29]. Commercial faecal antigen detection assays, using monoclonal antibodies, are available to distinguish E. histolytica from the other microscopically identical species.

Entamoeba histolytica exists in a vegetative form and as cysts, which survive outside the body, often for several months, and are highly infectious. The cystic form passes unharmed through the stomach and small intestine and excyts into the vegetative, trophozoite form in the colon. Here, after a variable period of time, which may be many years, it invades the mucosa, forming typical flask-shaped ulcers. Only 10% of those harbouring the parasite develop invasive amoebiasis.

Amoebae are carried to the liver in the portal venous system. Rarely, they pass through the hepatic sinusoids into the systemic circulation with the production of abscesses in lungs and brain.

Amoebae multiply and block small intrahepatic portal radicles with consequent focal infarction of liver cells. They produce a number of proteolytic enzymes which destroy the liver parenchyma. The resultant inflammation and necrosis leads to recruitment of neutrophils and the formation of microabscesses which coalesce. The lesions produced are usually single (in more than 60% of cases) and of variable size.

The amoebic abscess is usually about the size of an orange. The most frequent site is in the right lobe, often superoanteriorly, just below the diaphragm. The centre consists of a large necrotic area which has liquefied into thick, reddish-brown pus. This has been likened to anchovy or chocolate sauce. It is produced by lysis of liver cells. Fragments of liver tissue may be recognized in it. Initially, the abscess has no well-defined wall, but merely shreds of shaggy, necrotic liver tissue.

Histologically, the necrotic areas consist of degenerate liver cells, leucocytes, red blood cells, connective tissue strands and debris. Amoebae may be identified in the abscess wall. Hepatocyte death is by apoptosis, with evidence of activation of both extrinsic and intrinsic pathways [30].

Small lesions heal with scars, but larger abscesses show a chronic wall of connective tissue of varying age.

The lesion is focal and liver away from the abscess or microabscesses is normal.

Secondary bacterial infection of the abscess occurs in about 20%. The pus then becomes green or yellow and foul smelling.

Epidemiology

Colonic amoebae have a worldwide distribution, but hepatic amoebiasis is a disease of the tropics and subtropics. Endemic areas are Africa, south-east Asia, Mexico, Venezuela and Colombia. The majority of abscess cases occur in young adult males.

In temperate climates, symptomless carriers of toxic strains are often found without colonic ulcers. They are frequent commensals in men who have sex with men, although invasive disease is being increasing described in this population in the Far East [31,32].

In the tropics a new arrival is heavily exposed, especially when sanitation is poor. Locals are less prone, presumably because of partial immunity induced by repeated contact.

The latent period between the intestinal infection and hepatic involvement has not been explained.

Clinical Features

A history of travel or residence in tropical or subtropical areas is usually elicited. Amoebic dysentery is associated in only 10% and cysts in the stool in only 15%. Past history of dysentery is rare. Hepatic amoebiasis has been recorded as long as 30 years after the primary infection. Multiple abscesses are frequent in such areas as Mexico and Taiwan.

The onset is usually subacute with symptoms lasting up to 6 months. Rarely, it may be acute with rigors and sweating and a duration of less than 10 days. Fever is variously intermittent, remittent or even absent unless an abscess becomes secondarily infected; it rarely exceeds 40°C. Deep abscesses may present simply as fever without signs referable to the liver.

Jaundice is unusual and, if present, mild. Bile duct compression is rare.

The patient looks ill, with a peculiar sallowness of the skin, like faded suntan.

Pain in the liver area may commence as a dull ache, later becoming sharp and stabbing. If the abscess is near the diaphragm, there may be referred shoulder pain accentuated by deep breathing or coughing. Alcohol makes the pain worse, as do postural changes. The patient tends to lean to the left side; this opens up the right intercostal spaces and diminishes the tension on the liver capsule. The pain increases at night.

A swelling may be visible in the epigastrium or bulging the intercostal spaces. Hepatic tenderness is virtually constant. It may be elicited over a palpable liver edge or by percussion over the lower right chest wall. The spleen is not enlarged.

The lungs may show consolidation of the right lower zone, consolidation or an effusion. Pleural fluid may be blood stained.

Examination of Faeces.

Cysts and vegetative forms are rare.

Serological Tests

There are a number of test formats for detecting anti-Entamoeba antibodies, the commonest being enzyme immunoassay (EIA) and fluorescent antibody assays. IgG antibodies remain positive for some time after clinical cure. Amoebic abscess is unlikely if these tests are negative [33].

Biochemical Tests

In chronic cases, serum alkaline phosphatase values are usually about twice normal. Increases in transaminases are found only in those who are acutely ill or with severe complications. A rise in serum bilirubin is unusual except in those with superinfection or rupture into the peritoneum.

Radiological Features

Chest X-ray may show a high right diaphragm, obliteration of the costophrenic and cardiophrenic angles by adhesions, pleural effusion or right basal pneumonia. A right lateral abscess may cause widening of the intercostal spaces. The liver shadow may be enlarged with a raised immobile right diaphragm. The abscess commonly causes a bulge in the anteromedial part of the right diaphragm.

An abscess in the left lobe of the liver may produce a crescentic deformity of the lesser curve of the stomach.

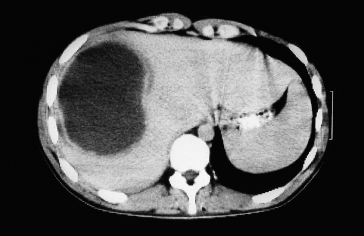

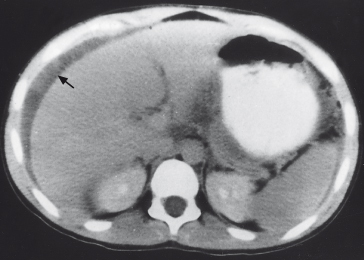

Ultrasound scan is the most useful for large abscesses and for follow-up. CT shows the abscess with a somewhat irregular edge and low attenuation (Fig. 32.4). It is more sensitive than ultrasound for small abscesses. It may show extrahepatic involvement, for instance in the lung [34].

Fig. 32.4. CT scan of the liver in a 21year old man with fever and right upper quadrant pain. Ultrasound scan had not shown a definite abnormality, presumably due to the echogenicity of the pus being close to normal liver. The CT shows a large space-occupying lesion from which 1 litre of pus was drained. This was an infected amoebic abscess.

MRI can also be used for diagnosis and to follow treatment [35]. Liquefaction of the cavity may be shown as early as 4 days after starting treatment [35].

Diagnostic Criteria

Diagnostic criteria are:

- History of exposure in an endemic area

- An enlarged, tender liver in a young male

- Response to metronidazole

- Leucocytosis without anaemia in those with a short history, and less marked leucocytosis and anaemia with a long history

- Suggestive posteroanterior and lateral chest X-ray

- Scanning showing a filling defect

- A positive amoebic fluorescent antibody test.

Complications

Rupture into the lungs or pleura causes empyema, hepatobronchial fistula or pulmonary abscess. The patient coughs up pus, develops pneumonitis or lung abscess or a pleural effusion.

Rupture into the pericardium is a complication of amoebic abscess in the left lobe.

Intraperitoneal rupture results in acute peritonitis. If the patient survives the initial event, long-term results are good. Abscesses of the left lobe may perforate into the lesser sac.

Rupture into the portal vein, bile ducts or gastrointestinal tract is rare.

Secondary infection is suspected if prostration is particularly great, and fever and leucocytosis high. Aspiration reveals yellowish, often fetid, pus and culture reveals the causative organism.

Treatment

Metronidazole, 750 mg three times a day for 5–10 days, has a 95% success rate. The time to defervescence is 3–5 days [18]. Failures may be related to the persistence of intestinal amoebiasis, drug resistance or inadequate absorption.

The time taken for the abscess to disappear depends on its size and varies from 10 to 300 days [36].

Aspiration is rarely necessary even with very large abscesses [37]. It should be done under ultrasound or CT guidance. A tense abscess in the left lobe that is likely to rupture into the peritoneum demands aspiration. Other indications are failure to respond after 4–5 days’ treatment and secondary bacterial infection [29]. The mortality from amoebic liver abscess should be zero [18].

A course of oral amoebocide, such as diloxanide furoate, should be given to cover amoebae persisting in the gut.

Tuberculosis of the Liver

Abdominal tuberculosis is more common in immigrants from developing countries and also increasingly in patients with AIDS [38].

The liver may be involved as part of miliary tuberculosis or as local tuberculosis where evidence of extrahepatic disease is not obvious. Rarely, hepatic tuberculosis can cause fulminant liver failure [39].

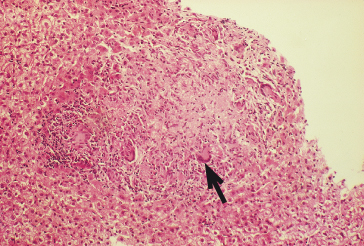

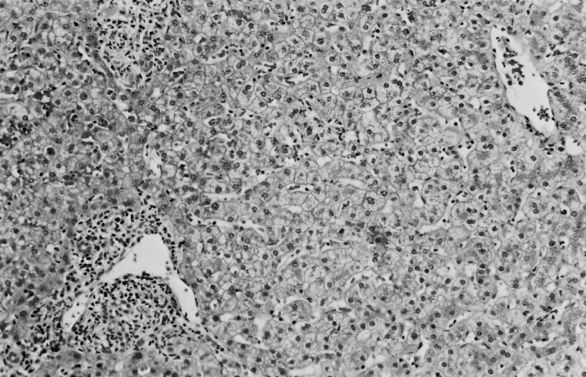

The basic lesion is the granuloma, which is very frequent in the liver in both pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis (Fig. 32.5). The lesions usually heal without scarring but sometimes with focal fibrosis and calcification.

Fig. 32.5. Miliary tuberculosis: a caseating granuloma contains lymphocytes, epithelial cells and numerous giant cells (arrow). There is central caseation.

Pseudotumoral hepatic tuberculomas are rare [40]. There may be no evidence of extrahepatic tuberculosis [41]. The tuberculomas may be multiple, consisting of a white, irregular, caseous abscess surrounded by a fibrous capsule (Fig. 32.6). The distinction from Hodgkin’s disease, secondary carcinoma or actinomycosis by naked-eye appearance may be difficult. Occasionally, the necrotic area calcifies.

Fig. 32.6. Hepatosplenic tuberculosis. CT scan showing scattered filling defects in the liver and spleen. Aspirate showed acid-fast bacilli and the culture was positive.

Tuberculous cholangitis is extremely rare, resulting from spread of caseous material from the portal tracts into the bile ducts.

Biliary stricture is a rare complication [42].

Tuberculous pylephlebitis results from rupture of caseous material. It is usually rapidly fatal although chronic portal hypertension can result [43].

Tuberculous glands at the hilum may lead rarely to biliary obstruction.

Clinical Features

These may be few or absent. The condition may present as a pyrexia of unknown origin, together with the typical features of tuberculosis: night sweats and weight loss. Jaundice may appear in overwhelming miliary tuberculosis, particularly in the racially susceptible. Rarely, multiple caseating granulomas lead to massive hepatosplenomegaly and death in liver failure [39].

Biochemical Tests

Serum globulin is increased so that the albumin/ globulin ratio is reduced. Alkaline phosphatase is disproportionately elevated [41].

Diagnosis

Initial diagnosis may be difficult, with few features pointing to hepatic involvement in many cases. Tuberculomas in liver and spleen are difficult to differentiate from lymphoma. Liver biopsy is essential. The indications are unexplained fever and weight loss with hepatomegaly or hepatosplenomegaly. A portion of the biopsy should be stained for acid-fast bacilli and cultured. Positives are obtained in about 50%. The diagnosis may be expedited by the use of PCR. The patient may have other supportive evidence of tuberculosis, such as a positive tuberculin or interferon-γ release test, although these are insufficient to distinguish active tuberculosis from latent disease [44].

A plain X-ray of the abdomen may reveal hepatic calcification. This may be multiple and confluent in tuberculoma, discrete and scattered and of uniform size, or large and chalky adjoining a stricture in the common bile duct [45].

CT may show a lobulated mass or multiple filling defects in liver and spleen (Fig. 32.6).

Extrahepatic features of tuberculosis may not be obvious.

Treatment is that for extrapulmonary tuberculosis, with four agents for the first 2 months (usually rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol) followed by two agents for at least a further 4 months [46].

The Effect on the Liver of Tuberculosis Elsewhere

Amyloidosis may complicate chronic tuberculosis. Fatty change is due to wasting and toxaemia. Drug jaundice may follow therapy, especially with isoniazid, rifampicin and pyrazinamide, and may result in fulminant hepatic failure.

Other Mycobacteria

Atypical mycobacteria can produce a granulomatous hepatitis, particularly as part of the AIDS syndrome (see Chapter 22). Mycobacterium scrofulaceum can cause a granulomatous hepatitis, characterized by a rise in alkaline phosphatase, tiredness and low-grade fever. Isolation of the organism requires liver biopsy culture [47]. Treatment is usually with non-standard regimens and depends upon susceptibility results.

Hepatic Actinomycosis

Hepatic involvement due to Actinomyces species is usually a sequel to intestinal actinomycosis, especially of the caecum and appendix, occurring in 15% of cases of abdominal actinomycosis [48]. It spreads by direct extension or, more often, via the portal vein, but can be primary. Large greyish-white masses, superficially resembling malignant metastases, soften and form collections of pus, separated by fibrous tissue bands, simulating a honeycomb. The liver becomes adherent to adjacent viscera and to the abdominal wall, with the formation of sinuses. These lesions contain the characteristic ‘sulphur granules’, which consist of branching, Gram-positive filaments with eosinophilic, clubbed ends. It should be noted that the infection is mixed (particularly with other anaerobes) in more than 30% of cases [49].

Clinical Features

The patient is often toxic, febrile, sweating, wasted and anaemic. There is local, sometimes irregular, enlargement of the liver with tenderness of one or both lobes. The overlying skin may have the livid, dusky hue seen over a taut abscess that is about to rupture. Multiple, irregular sinus tracks develop. Similar sinuses may develop from the ileocaecal site or from the chest wall if there is pleuropulmonary extension.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis should be suspected in patients developing sinus tracts, and the organism can be isolated from the pus. If actinomycosis is suspected before this stage, percutaneous liver biopsy may reveal sulphur granules with typical organisms [50].

Early presentation is as pyrexia, hepatosplenomegaly and anaemia. It may be months before multiple abscesses are detected, often by ultrasound, CT [51] or MRI [52]. Anaerobic blood cultures may be positive.

Treatment

Intravenous penicillin in high doses is the mainstay of treatment. Alternative agents are doxycycline and clindamycin. Therapy is usually needed for at least 4 weeks and continuation with oral therapy after this time may be appropriate [49]. However, additional, or alternative agents may be needed to cover other bacteria in those with mixed infections, at least for the initial period. Surgical resection may be necessary [53].

Syphilis of the Liver

Congenital

The fetal liver is heavily infected by any transplacental infection. It is firm, enlarged and swarming with spirochaetes. Initially, there is a diffuse hepatitis, but gradually fibrous tissue is laid down between the liver cells and in the portal zones, and this leads to a true pericellular cirrhosis.

Since hepatic involvement is but an incident in a widespread spirochaetal septicaemia, the clinical features are seldom those of the liver disease. The fetus may be stillborn or die soon after birth. If the infant survives, other manifestations of congenital syphilis are obvious, apart from the hepatosplenomegaly and mild jaundice. In recent years, syphilis is a rare cause of neonatal jaundice.

In older children who have survived without this florid neonatal picture, the hepatic lesion may be a gumma.

Diagnosis can be confirmed by blood serology, which is always positive.

Secondary

In the secondary septicaemic stage, spirochaetes produce miliary granulomas [54].

Fifty per cent of sufferers have raised serum enzyme levels [55], although clinical hepatitis is rare. However, sometimes the picture is of severe cholestatic jaundice [56].

Serology is positive with raised reagin (VDRL or RPR assays) and syphilis-specific antibody titres. Serum alkaline phosphatase levels are high. The M1 cardiolipin fluorescent antimitochondrial antibody is positive and becomes normal with recovery [56].

Liver biopsy shows non-specific changes with moderate infiltration with polymorphs and lymphocytes, and some hepatocellular disarray, but cholestasis is absent or mild except in the severely cholestatic patients [56]. Portal-to-central zone necrosis can be seen (Fig. 32.7). Spirochaetes are sometimes detected in the liver biopsy if special stains are used.

Fig. 32.7. Liver in secondary syphilis. Mononuclear cell infiltration can be seen in portal zones and in the sinusoids. (H & E, ×160.)

Tertiary

Gummas may be single or multiple. They are usually in the right lobe. They consist of a caseous mass with a fibrous capsule. Healing is followed by deep scars and coarse lobulation (hepar lobatum).

Hepatic gummas are usually diagnosed incidentally, by ultrasound or CT, at surgery or at autopsy. Ultrasound-guided biopsy of a nodule shows aseptic necrosis, granulomas and spirochaetes [57]. Serology is positive. Antibiotic treatment is successful.

Treatment

All cases of syphilis should be managed in conjunction with a genitourinary physician. First-line treatment remains penicillin in the form of benzathine or procaine penicillin (or benzylpenicillin in the case of congenital syphilis). Alternative agents include other beta-lactams, doxycycline and macrolides [58].

Jaundice Complicating Penicillin Treatment

Rarely, the patient shows an idiosyncrasy to penicillin. Jaundice, chills and fever, often with a rash (erythema of Milan), occur about 9 days after starting therapy. This is part of the Herxheimer reaction. The mechanism of the jaundice is unclear.

Perihepatitis

This upper abdominal peritonitis is associated with genital infections, particularly those due to Chlamydia trachomatis and less often, Neisseria gonorrhoeae [59]. It affects young, sexually active women and simulates biliary tract disease. Diagnosis is by laparoscopy. The liver surface shows white plaques, tiny haemorrhagic spots and ‘violin string’ adhesions.

CT may also show ‘violin string’ adhesions (Fig. 32.8) [60]. Treatment is as for pelvic inflammatory disease, usually with a combination of a third-generation cephalosporin and doxycycline [61].

Fig. 32.8. CT in chlamydial perihepatitis shows ‘violin string’ adhesions between liver and anterior abdominal wall (arrowed) and ascites.

Leptospirosis

Pathogenic Leptospira related to human disease can be classified by DNA typing into 250 serovars belonging to 24 serogroups [62]. The disease due to Leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae was described by Weil in 1886 [63]. It is a severe infection spread by the urine of infected rats. The whole group of leptospiral infections should be designated leptospirosis.

Weil’s Disease

Mode of Infection

Living Leptospira are continually excreted in the urine of infected rats and survive for months in pools, canals, flood water or damp soil. The patient is infected by contaminated water or by direct occupational contact with infected rats. Those affected include participants in water sports, agricultural and sewer workers and fish cutters. Cities in Europe, South and Central America and Asia (such as the favelas of Brazil), where rat populations are expanding, provide a source of infection [64]. The disease is most prevalent in late summer and autumn in temperate regions.

Pathology

Histopathological changes are slight in relation to the marked functional impairment of kidneys and liver. The damage is at a subcellular level. Non-esterified fatty acids from the cell wall of the spirochaetes have been suggested to play an important role in the development of acute tubular necrosis, and outer membrane protein extracts have been shown to stimulate a proinflammatory cytokine response via TLR2 receptors in the renal tubules [65]. Plasma tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) levels have been related to the severity of organ involvement [66].

Liver necrosis is minimal and focal [67]. Zone 3 necrosis is absent. Active hepatocellular regeneration, shown by mitoses and nuclear polyploidy, is out of proportion to cell damage. Swollen Kupffer cells contain leptospiral debris. Leucocyte infiltration and bile thrombi are prominent in the deeply jaundiced. Cirrhosis is not a sequel.

The kidneys shows tubular necrosis and interstitial nephritis.

Skeletal muscle shows punctate haemorrhages and focal necrosis.

The heart may show haemorrhages in all layers.

Haemorrhage into tissues, especially skin and lungs, is due to capillary injury and thrombocytopenia.

Jaundice is related to hepatocyte dysfunction magnified by renal failure impairing urinary bilirubin excretion. Tissue haemorrhages and haemolysis increase the bilirubin load on the liver. Hypotension with diminished hepatic blood flow contributes.

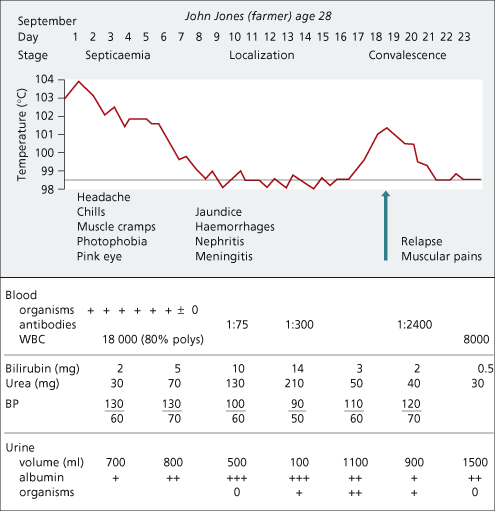

Clinical Features (Fig. 32.9)

The clinical picture is not pathognomonic and the disease is heavily under-diagnosed. It is more often anicteric than icteric. The incubation period is 2–14 days [68]. The course may be divided into three stages: the first or septicaemic phase lasts for about 7 days, the second or toxic stage for a similar period, and the third or convalescent period begins in the third week.

The first or febrile stage is marked by the presence of the spirochaete in the circulating blood.

The onset is abrupt, with prostration, high fever and even rigors. The temperature rises rapidly to 39.5–40.5°C and falls by lysis within 3–10 days.

Abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting may simulate an acute abdominal emergency, and severe muscular pains, especially in the back or calves, are common.

Central nervous system involvement is shown by severe headache, mental confusion and sometimes meningism. The cerebrospinal fluid confirms meningeal involvement. If jaundice is present, there is xanthochromia.

The eyes show a characteristic suffusion.

In those with severe disease, bleeding may occur from nose, gut or lung, with skin petechiae or ecchymoses.

Pneumonitis with cough, sore throat and rhonchi occurs in 40% of sufferers and in some cases this may progress to haemorrhagic pulmonary disease (severe pulmonary haemorrhage syndrome) or adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Jaundice appears between the fourth and seventh day in 80% of patients. It is a grave sign, for the disease is never fatal in the absence of icterus. The liver is enlarged, but not the spleen.

The urine shows albumin and bile pigment. The stools are well coloured.

There is a leucocytosis of 10–30 × 109/L with a relative increase in polymorphs. Thrombocytopenia may be profound and other clotting abnormalities may be present, such as a prolonged prothrombin time [69].

The second or icteric stage in the second week is characterized by a normal temperature but without clinical improvement. This is the stage of deepening jaundice, with increasing renal and myocardial failure. Albuminuria persists, there is a rising blood urea, and oliguria may proceed to anuria. Death may be due to renal failure. A markedly elevated creatinine phosphokinase level reflects myositis.

Severe prostration is accompanied by a low blood pressure and a dilated heart. There may be transient cardiac dysrhythmias and electrocardiograms may show a prolonged P–R or Q–T interval, with T-wave changes. Death may be due to circulatory failure.

During this stage, the Leptospira can be found in the urine, and rising antibody titres demonstrated in the serum.

The third or convalescent stage starts at the beginning of the third week. Clinical improvement is shown by a brightening of the mental state, fading of the jaundice, a rise in blood pressure and an increased urinary volume, with a drop in the blood urea concentration. Albuminuria is slow to disappear.

Temperature may rise during the third week (Fig. 32.9), associated with muscle pains. Such relapses occur in 20% of cases.

There is great variation in the clinical course ranging from a mild illness, clinically indistinguishable from influenza, to a prostrating, fatal disease with anuria.

Diagnosis

Before the appearance of antibodies, PCR demonstration of Leptospira is the best method of diagnosis [70].

Rising titres of antibodies are sought by Dot-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [71] or immunofluorescence [72]. The microscopic agglutination test is considered the gold standard assay and is usually performed by reference laboratories [73].

Leptospira may be cultured from blood during the first 10 days. Urine cultures are positive during the second week and persist for several months. Culture is laborious and less sensitive than molecular methods, but allows serovar identification, that is serological typing using serum-containing antibodies against different antigens.

Liver function tests are non-contributory.

Differential Diagnosis

In the early stages, Weil’s disease may be confused with septicaemic bacterial infections or typhus fever. When jaundice is evident acute viral hepatitis must be excluded (Table 32.2). Important distinguishing points are the sudden-onset, increased polymorph count and albuminuria of Weil’s disease.

Table 32.2. The differential diagnosis of Weil’s disease from viral hepatitis during the first week of illness

| Weil’s disease | Viral hepatitis | |

| Onset | Sudden | Gradual |

| Headache | Constant | Occasional |

| Muscle pains | Severe | Mild |

| Conjunctival injection | Present | Absent |

| Prostration | Great | Mild |

| Disorientation | Common | Rare |

| Haemorrhagic diathesis | Common | Rare |

| Nausea and vomiting | Present | Present |

| Abdominal discomfort | Common | Common |

| Bronchitis | Common | Rare |

| Albuminuria | Present | Absent |

| Leucocyte count | Polymorph leucocytosis | Leucopenia with lymphocytosis |

Spirochaetal jaundice would be diagnosed more often if blood samples for antibodies were taken from patients with obscure icterus and fever.

Prognosis

Mortality varies from less than 1% to more than 20% [73]. This depends on the depth of jaundice, renal and myocardial involvement, and the extent of haemorrhages. Death is usually due to renal failure. The mortality is negligible in non-icteric patients, and is lower in those under 30 years old. Since many mild infections are probably unrecognized, the overall mortality may be considerably less.

Although transient relapses in the third and fourth weeks are common, final recovery is complete.

Prevention

Protective clothing should be provided for workers in industries with a high incidence of Weil’s disease, and adequate measures taken to control rodents. Bathing in stagnant water should be avoided.

Treatment

Early, mild leptospirosis may be treated by doxycycline (100 mg by mouth) twice daily for 1 week. More seriously ill patients, particularly with vomiting, may be treated with high-dose benzylpenicillin or cephalosporins for 1 week [74,75]. Aminoglycosides and macrolides have also been successfully used [73].

Prognosis is improving with earlier diagnosis, attention to fluid and electrolyte balance, renal dialysis, antibiotics and circulatory support.

Other Types of Leptospirosis

In general, these infections are less severe than those due to L. icterohaemorrhagiae. L. canicola infection, for example, is characterized by headache, meningitis and conjunctival infection. Albuminuria is only found in 40%, and jaundice in only 18% of patients. The frequent presentation is that of ‘benign aseptic meningitis’. The disease affects young adults who have usually been in close contact with an infected dog. Fatalities in humans are virtually unknown.

Diagnosis is confirmed in a similar way to Weil’s disease. The spinal fluid shows a lymphocytic picture in most cases.

Relapsing Fever

This arthropod-borne infection is caused by spirochaetes of the genus Borrelia. Borrelia recurrentis is the cause of louse-borne relapsing fever, now only found in Ethiopia and surrounding countries, whereas tick-borne relapsing fever is caused by at least 15 different Borrelia species around the world and is reported in North and South America, Africa, Asia and Europe.

The Borrelia multiply in the liver, invading liver cells and causing focal necrosis. Just before the crisis the Borrelia roll up and are ingested by reticuloendothelial cells. Surviving Borrelia remain in the liver, spleen, brain and bone marrow until the next relapse [76]. Subsequent immune ‘escape’ is due to vmp antigenic variation [77].

Clinical Features [78]

The incubation period is 4–14 days. The onset is acute with chills, a continuous high temperature, headache, muscle pains and profound prostration. The patient is flushed, sometimes with injected conjunctivae, and epistaxes. In severe attacks, tender hepatosplenomegaly and jaundice develop. The jaundice is similar to that of Weil’s disease. Sometimes a rash develops on the trunk. There may be bronchitis.

These symptoms continue for 4–9 days and then the temperature falls, often with collapse of the patient. This may be fatal, but more usually the symptoms and signs then rapidly abate, the patient remains afebrile for about 1 week, when there is a relapse. There may be a second or even a third milder relapse before the disease ends.

Diagnosis

Spirochaetes can rarely be found in thick blood films and molecular methods are increasingly being used [79]. Agglutination and complement fixation tests are available [76]. Organisms may be identified by lymph node aspiration, or from the insect bite site.

Treatment

Tetracyclines and streptomycin are more effective than penicillin. Erythromycin and ceftriaxone are also effective [77]. Mortality is 2–5% without treatment.

Lyme Disease

This is due to a tick-borne spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. It has been reported to cause hepatitis with numerous liver cell mitoses [80] and also granulomatous hepatitis [81]. Mild liver function test abnormalities are frequent in the early erythema migrans stage, but these resolve with antibiotic treatment [82]. Lyme disease does not seem to cause permanent hepatic sequelae.

Rickettsial Infections

Q Fever

This disease usually has predominantly pulmonary manifestations. Although frank jaundice is uncommon, hepatomegaly and elevated aminotransferases are common and clinical features may mimic anicteric viral hepatitis [83,84,85].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree