- Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic and relapsing, immune-mediated liver injury.

- No single diagnostic test exists for AIH and in the absence of alternative liver disease, diagnosis rests on the presence of a constellation of laboratory and histological features.

- Successful treatment with steroids and azathioprine is generally very effective in the induction of disease remission and maintenance free of relapse.

- In children, overlap presentation with a biliary disease (just sclerosing cholangitis) occurs in approximately 50% of patients (but much less often in adults).

- Non-compliance with therapy is the commonest reason for treatment failure; management of this chronic disease must be sensitive to individual patient concerns and circumstances.

Introduction

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) describes a condition characterized by chronic and relapsing lymphoplasmacytic hepatitis, which is usually associated with positive autoimmune serology and elevated immunoglobulins.1–4 More importantly, drug injury, viral hepatitis, Wilson disease, and metabolic liver disease need to be excluded to confirm diagnosis. This disease is protean in its presentation, ranging from fulminant liver failure through to chronic asymptomatic hepatitis. The generally excellent and durable response to steroids and azathioprine clinically distinguishes this disease. There is no such thing as a classic AIH patient. This disease is more prevalent in younger women but it is also clearly recognized in men, and in patients of all ages. Autoimmune serology is used to broadly classify patients into two groups, although these two groups are treated similarly: type 1 disease with positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA) or smooth muscle antibodies (SMA), and type 2 disease, a predominantly pediatric disease at presentation, with anti-liver–kidney–microsomal (LKM) antibodies. Type 2 AIH is distinctly uncommon in North America, most patients having type 1 disease.

Differential Diagnosis

It is essential to consider other diagnoses before treating a patient for AIH, given the recognized deleterious side effects of immunosuppression. Exclusion of alternative etiologies for liver disease relies on a suitably detailed history from the patient that includes details of prescribed and unprescribed drug ingestion, as well a thorough liver screen. It is important to recognize that no single test can diagnose AIH, and one must appreciate the limitations of such tests.

Pediatric

Wilson Disease.

This is described in greater detail in Chapter 23. Particularly in a patient under the age of 21(but to some extent in all patients), Wilson disease must be carefully considered and excluded. Those with Wilson disease can have elevated IgG levels and positive autoimmune markers.

Minocycline Hepatitis.

Many drugs can give a hepatitic picture, and a few drugs can mimic all the features of AIH. In the pediatric age group, minocycline hepatitis must be considered as such patients may have a transaminitis, positive ANA or SMA, and elevated immunoglobulins (and patients respond to corticosteroids when removal of the offending drug is all that is needed).

α1-Antitrypsin Deficiency.

This entity is relatively straightforward to diagnose clinically—one can measure serum levels of α1-antitrypsin and stain for α1 inclusions on liver biopsy. Some patients with α1-antitrypsin can present with a hepatitic picture, without a history of neonatal cholestasis.

Adults

Drug Injury.

As alluded to above, many prescribed drugs and herbal remedies can present with a hepatitis. Fortunately, the hepatitis is usually self limiting if the exposure to the offending agent is halted. The list of injurious agents is lengthy and increases each year. Usually, the injury is non-specific and does not have etiologic clues other than from the patient history. Nitrofurantoin is frequently used for the treatment of recurrent urinary tract infections and minocycline for acne; in a minority of patients, it has very characteristic acute and chronic hepatic side effects. In its classic form, nitrofurantoin hepatitis is entirely indistinguishable from AIH. Antitumor necrosis factor agents have also been reported to be associated with development of AIH.

Primary Biliary Cirrhosis.

Whilst true overlap syndromes between different autoimmune liver diseases are distinctly rare, it is quite common for patients with primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) to present with an elevated alkaline phosphatase that is accompanied by a transaminitis. Usually, the transaminases are less than five times the upper limit of normal. Liver biopsy in PBC can also frequently show an interface hepatitis. It is important to treat the predominant process, and usually ursodeoxycholic acid is sufficient. The serologic hallmark for PBC (AMA) may be detectable although rarely a true overlap with PBC is present.

Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC).

At younger ages, PSC presentation can be more hepatitic, and in children (see Chapter 20), 50% of patients with AIH have a sclerosing cholangiopathy and vice versa. PSC should also be entertained as a differential diagnosis in patients who do not respond well to immunosuppression.

Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD).

Low titer autoantibodies (ANA/SMA) alongside minor elevations in IgG are surprisingly common. Given the vast number of patients with NAFLD, it is therefore imperative to avoid over interpretation of such findings in patients with usually relatively minor elevations in transaminases. Additionally, accurate liver biopsy interpretation is important, given that steatohepatitis and Mallory bodies are not features of AIH.

Viral Hepatitis.

The exclusion of concomitant active viral liver disease is a prerequisite for making a diagnosis of AIH. An overlap between hepatitis C and AIH is not a common clinical reality, although making this distinction can be difficult. The frequent presence of autoantibodies (ANA, SMA) in hepatitis C is neither sufficient to diagnose AIH nor to be of any relevance in the management of the hepatitis C. Given the epidemiology of hepatitis B, there are inevitably patients at different stages of viral hepatitis that might also develop AIH. Such patients need to be evaluated on an individual basis, and have their hepatitis B treated first with oral nucleoside analogues if HBsAg positive before any corticosteroids are given.

Miscellaneous.

AIH can present in a variety of ways from acute liver failure to anicteric asymptomatic transaminitis, and so metabolic and infiltrative disorders can sometimes be pertinent items on the differential diagnosis. Clinicians should avoid indiscriminate testing for autoantibodies if an appropriate diagnosis already exists; positive serology for ANA or SMA are far more common in the general population than is AIH.5 Very rarely, severe untreated celiac disease can mimic autoimmune liver disease, so serologic testing and subsequent duodenal biopsy should be considered.

Making the Diagnosis

Presentation

Clinically, the presentation of AIH spans the breadth of all liver disease—patients may present asymptomatically with only a biochemical transaminitis found incidentally, through to acute liver failure. At the time of histological diagnosis, AIH is usually a chronic inflammatory process, and one-third of patients are cirrhotic. When symptoms are present, they are usually non-specific, such as fatigue, arthralgias, and upper abdominal pain. If the patient is very cholestatic, they may be jaundiced but rarely complain of pruritus.

Pediatric Perspective

Type 1 AIH accounts for two-thirds of the cases and usually presents during adolescence, while type 2 AIH presents at a younger age (<10 years) and also during infancy. In both types there is a female preponderance (75%). Children are more likely to have symptomatic disease, which triggers investigation. Systemic symptoms such as arthralgias are frequent; amenorrhea may be present. Acne may also flare. Type 2 AIH (LKM antibody positive) is more likely to be severe at presentation, with higher rates of cirrhosis. However, treatment for both types of AIH is the same.

Investigations

It should always be remembered that AIH is a diagnosis of exclusion. Clinical scoring systems (Table 19.1)6 are helpful, but their intended purpose is often for research studies (i.e. uniformity in patient inclusion). Therefore, not all patients in all scenarios can necessarily be evaluated by these systems. Finally, no test in isolation can diagnose AIH. Seronegative disease is well described and behaves identically in terms of treatment response.

Table 19.1 Simplified autoimmune hepatitis scoring system6

| Parameter | Classifier | Score |

| ANA or SMA | ≥1 : 40 | 1 |

| ANA or SMA | ≥1 : 80 | |

| or LKM | ≥1 : 40 | 2 |

| IgG | > ULN | 1 |

| >1.10 × ULN | 2 | |

| Liver histology | Compatible AIH | 1 |

| Typical AIH | 2 | |

| Absence of viral hepatitis | Yes | 2 |

SCORE: ≥6 “probable” AIH; ≥7 “definite” AIH.

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; ANA, antinuclear antibodies; LKM, anti-liver–kidney–microsomal antibodies; SMA, smooth muscle antibodies; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Diagnostic Blood Work.

After the exclusion of common liver injuries such as hepatitis B and C, testing includes:

- Serum autoantibodies: type 1 AIH is characterized by the presence of ANA or SMA. Whilst ELISA-based assays for F-actin can reliably detect the antigen most associated with SMA, this is not the case for ELISA-based ANA assays, given the lack of ANA specificity in AIH. Therefore clinicians concerned about autoimmune liver disease should insist on immunofluorescence testing particularly for ANA.

- Type 2 disease, almost always a pediatric disease at presentation, is very uncommon in North America, and is characterized by LKM antibodies. Particularly in adults, clinicians should request immune serology in a sequential manner—ANA and SMA first, with additional testing for LKM antibodies only if the patient is ANA/SMA negative. In routine practice most clinicians do not have access to other specific AIH serology, for example anti-soluble liver antigen. Mitochondrial antibodies can be positive in AIH, especially when determined by immunofluorescence. Their presence does not necessarily mean the patient has an overlap syndrome with PBC, since true AMA-positive AIH is reported to behave identically to type I AIH.

- Immunoglobulins: most commonly, patients with AIH have elevated IgG values at presentation, usually at least twice the upper limit of normal. It is essential to measure IgG in all patients suspected of having AIH. If the presentation is very acute, IgG titers may be normal initially and thus should be repeated a few weeks later. Remember, non-specific elevations in IgG can be seen in any cause of cirrhosis as well as other systemic inflammatory conditions. It is important to measure IgG levels as relapse of disease can often be identified if the IgG begins to rise towards pretreatment levels. In children, IgG is usually raised at presentation, although 15% of children with type 1 AIH and 25% with type 2 AIH have normal levels, especially those with an acute presentation. IgA deficiency is common in type 2 AIH.

- α1-Antitrypsin and ceruloplasmin levels should be measured in order to screen for rare patients with α1-antitrypsin deficiency or Wilson disease. If the suspicion is high for Wilson disease (e.g. acute presentation of young patient with an unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia and a relatively low alkaline phosphatase) urine copper and ophthalmic evaluation for Kayser–Fleischer rings should be performed, as well as possibly measuring hepatic copper concentration.

Imaging.

Baseline ultrasound imaging is usually sufficient in the workup of patients. Such imaging should always include Doppler interrogation of the portal and hepatic veins. Cross-sectional imaging is not usually needed unless there is doubt as to the diagnosis, or if malignancy is suspected. Given the high frequency of biliary disease in children with AIH, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is indicated in all pediatric patients. The need for MRCP in all adult patients is debatable, for the frequency of overlap of AIH and biliary disease (namely PSC) is less than 10%. Thus, it can reasonably be reserved for those with clinical, laboratory, or histologic features of both AIH and biliary disease, or who fail to respond as expected to therapy. Cholestatic AIH is described predominantly in Africans.

Histology.

There are no specific features on histology that are unique to AIH. The degree of histologic change is also affected by the severity of presentation and whether immunosuppressive treatment has been initiated prior to biopsy. However, there are recurrent patterns of inflammation, including an interface hepatitis, lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, and hepatocyte rosetting, and albeit rarely zone 3 necrosis which help focus attention towards AIH (Plates 19.1 and 19.2). Liver biopsy is generally recommended as part of the diagnostic work up in all patients, given the nature, duration, and potential side effects of treatment of AIH. Exceptions to this rule may include those with acute liver failure, ascites, and the very elderly, where treatment may be initiated on the basis of history and blood work alone. However, if histology is omitted in patients such as these, great attention needs to be given to treatment response; a failure to respond to treatment should raise the possibility of an incorrect diagnosis, and may heighten the need for liver biopsy. The pathologist must be given adequate clinical information in order to interpret the liver histology correctly. Also when discussing the findings with the pathologist, the clinician should probe for important differentials that must not be missed, such as viral inclusion bodies or malignant infiltration. When there is a marked hepatitis (i.e. significant hepatocyte necrosis and architectural collapse) fibrosis evaluation is difficult and should not be relied upon until treatment has resolved the active inflammation.

Endoscopy.

Generally, endoscopy at presentation is not indicated. In patients with cirrhosis or decompensated disease, varices should be sought, as with any patient with advanced liver disease.

Bone Density.

It is sensible to establish the baseline bone density in adults either before starting therapy, or soon after. In combination with the patient’s age, gender, past medical history, and treatment plan, prophylaxis against bone loss may be indicated, i.e. milk and vitamin D.

Associated Autoimmune Diseases.

Routine screening for additional autoimmune disease is not normally pursued, although the presence of autoantibodies can be used as surrogate support for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Thyroid disease, rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, type 1 diabetes, and celiac disease are all associated with AIH.

Miscellaneous.

Hepatitis B testing should always be part of the initial investigation, and particular attention should be paid to high-risk patients (e.g. Asians) to screen for current (HBsAg) and past (HBcAb) infection. Patients with risk factors for infectious disease exposure (e.g. travel, intravenous drug use) should be screened for Strongyloides, tuberculosis, and HIV before immunosuppression.

Pediatric Perspective

The investigation for a pediatric patient is very similar to that of an adult. The most important difference is that Wilson disease must be aggressively excluded, and investigation must be timely and rapid as patients are often jaundiced and at risk of decompensated liver disease. MRCP is recommended for all patients as overlap with PSC is more common. Serologically false-positive associations are far less common, and for this reason autoantibody titers at a lower level (e.g. 1 in 20) carry diagnostic significance.

Management

In general, there are three phases to caring for a patient with AIH: (1) induction of remission (prednisone); (2) maintenance of remission (prednisone and azathioprine); and (3) prevention of relapse (azathioprine).

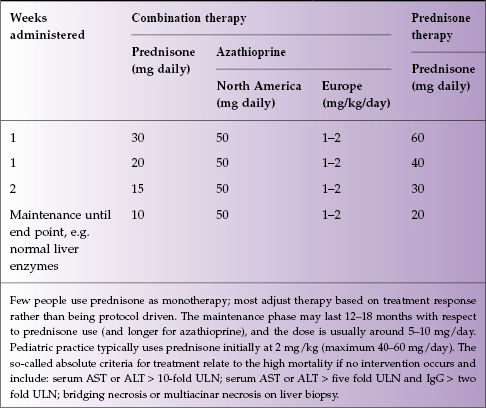

Because of the variability of patients, the paucity of current randomized data, and differences amongst experts, no one treatment algorithm is widely practiced. The AASLD guidance is a reasonable framework for non-hepatologists to use, with most people favoring joint therapy with prednisone and azathioprine (Table 19.2). On average, it takes 12–18 months (sometimes more) of steroids, with azathioprine at 1–2 mg/kg per day, to induce complete disease remission with sustained normalization of liver enzymes and immunoglobulins. Steroid withdrawal at that point can usually be accomplished without a repeat biopsy, especially if all tests are normal. Most clinicians then maintain patients on monotherapy with azathioprine for 2–5 years, and in a non-cirrhotic patient, one chance off all treatment may be allowed, with monitoring. If the patient is cirrhotic, or if they have had an episode of relapse off treatment, long-term maintenance with azathioprine is generally indicated, which is usually life long. Relapses must first be managed with steroids again (Box 19.1).

Table 19.2 Current AASLD treatment guidelines for AIH1