- Everyone infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) should be screened for hepatitis B and hepatitis C as all three viruses share routes of infection.

- Anyone with liver disease should be assessed (at least annually) for both activity of the liver disease and severity of underlying liver fibrosis, ideally using non-invasive methods to determine the presence of cirrhosis.

- Individuals with HIV and liver disease should ideally be cared for in settings with expertise in both HIV and liver disease.

Introduction

The natural history of HIV/AIDS has evolved rapidly from the inevitable death sentence of the 1980s and early 1990s to a chronic infection that can be controlled through the use of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). In the late 1990s, combination therapy was chosen from the drug classes of nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI), non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI), and protease inhibitors (PI). In 2011, additional classes of drugs became available, such as fusion inhibitors, entry inhibitors, and integrase inhibitors.1 The ability to target the HIV virus at so many sites of replication means that it is possible to completely suppress HIV replication in the large majority of infected individuals. The challenge of medication adherence remains. Fortunately, this is less problematic as the pill burden has decreased with the development of new drug formulations, allowing single-pill combination therapy and once-daily dosing regimens, as well as development of medications that minimize side effects. With HIV controlled, the major cause of mortality in those with HIV infection is now liver disease.2

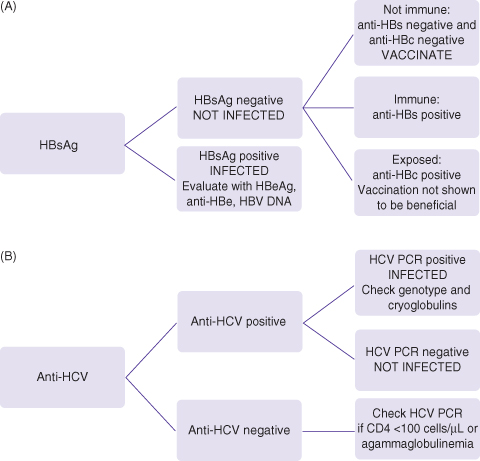

The evaluation of liver disease in HIV is difficult as the cause is frequently multifactorial even if the injuring agent was stopped many years in the past. There are many theories about mechanisms of liver injury in HIV but there is rarely the accompanying proof of the mechanism in the published literature. For example, a thorough history of alcohol consumption is almost never available in publications about other causes of liver disease. Everyone with HIV infection should be screened for hepatitis B and hepatitis C infection as all three viruses share common routes of infection (Fig. 18.1a and b). Everyone with risk behaviors that put them at risk for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection should be vaccinated. Arguably, screening should be done annually in those with ongoing high-risk behaviors for acquiring viral hepatitis. Hepatitis B testing and characterization for HBV activity with HBeAg (hepatitis B e antigen) status and HBV DNA viral load is rarely done in most centers as part of routine HIV care. Mitochondrial toxicity is postulated as a cause of liver disease in those with HIV on antiretroviral therapy but tests of mitochondrial function or electron microscopic studies of liver tissue for mitochondrial morphology are almost never done. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) is postulated but other factors such as rebounding hepatitis B, C, or D viremia suggesting viral reactivation are not routinely excluded. Thus, the approach to evaluating the liver of the individual must be a systematic approach with good communication between the hepatologist and the HIV specialist.

Fig. 18.1 (A) Screening for hepatitis B: check HBsAg, anti-HBs, IgG anti-HBc. (B) Screening for hepatitis C: check anti-HCV, confirm with HCV PCR. Everyone with HIV should be screened for hepatitis B (HBsAg, anti-HBs, anti-HBc) and hepatitis C (anti-HCV). Those who remain susceptible to HBV infection (HBsAg negative, anti-HBs negative, and anti-HBc negative) should be vaccinated. Many with HIV have been previously exposed to hepatitis B (anti-HBc positive) and it is unclear if they will benefit from vaccination. In those not currently infected and yet have behaviors associated with high risk of infection (multiple sexual partners, injection drug use), HBsAg and anti-HCV should be checked annually and whenever new ALT/AST elevation is observed.

Evaluation of HIV

Components of the evaluation of HIV infection are:

- year of HIV diagnosis and route of acquisition;

- CD4 nadir (lowest count) and current CD4;

- HIV viral load;

- medication history, noting especially:

- years of exposure to the D drugs: ddC (dideoxycytidine (Zalcitabine), an HIV-specific NRTI, FDA approved in 1992, no longer marketed), ddI (dideoxyinosine, an HIV-specific NRTI, FDA approved in 1991), d4T (stavudine (Zerit) an HIV-specific NRTI, FDA approved in 1994), as well as AZT (zidovudine, an HIV-specific NRTI, FDA approved in 1987)

- prior exposure to 3TC (lamivudine (Epivir), an HBV- and HIV-specific NRTI, FDA approved for HIV in 1995 and for HBV in 1998) when HBV infection may have been present, and so probability of 3TC-resistant HBV is high

- ATV (atazanavir (Reyataz) an HIV-specific PI) can dramatically raise the indirect (unconjugated) bilirubin without liver injury

- years of exposure to the D drugs: ddC (dideoxycytidine (Zalcitabine), an HIV-specific NRTI, FDA approved in 1992, no longer marketed), ddI (dideoxyinosine, an HIV-specific NRTI, FDA approved in 1991), d4T (stavudine (Zerit) an HIV-specific NRTI, FDA approved in 1994), as well as AZT (zidovudine, an HIV-specific NRTI, FDA approved in 1987)

The HIV history is important to the overall evaluation of an individual infected with HIV who has liver disease. The year of HIV diagnosis and route of acquisition is not only informative for assessment of risk behaviors, which may put them at ongoing risk for viral hepatitis, but it may give insight into how these individuals may react to any proposed therapy. For example, those with ongoing injection drug use may not place a high priority to antiviral therapies that may have a lot of side effects. Those who survived HIV infection in the 1990s and were exposed to many of the early HIV medications may be skeptical about unproven therapies. The CD4 count for HIV is similar to the degree of liver fibrosis for liver disease—both are measures of disease severity and markers for increased risk of complications once certain CD4 count thresholds are reached. Uncontrolled HIV infection leads to falling CD4 counts that are associated with increased risk of death once they fall below a certain threshold. The threshold for initiating HIV therapy has been a moving target but once below 200 cells/µL, the risk of opportunistic infections rises to the point that prophylactic antibiotics (sulfamethoxazole plus trimethoprim) are indicated. It is important to record the nadir CD4 count (the lowest recorded CD4) since the CD4 will rise with HIV suppressive therapy but if therapy is interrupted, the CD4 will rapidly fall to the nadir within a few months. The HIV viral load should be negative in the majority who are on effective cART. A detectable viral load suggests treatment failure due to poor adherence and/or drug resistance. The complete HIV medication history is important in several ways. The duration of exposure to “D drugs” (ddC, ddI, d4T) and perhaps long-term use of AZT may have led to mitochondrial injury and predispose patients to nodular regenerative hyperplasia, a form of non-cirrhotic portal hypertension. Atazanavir raises the indirect (unconjugated) fraction of bilirubin, which does not seem to be associated with liver injury. Any medication started within the last 12 months should be noted as it may be responsible for an idiosyncratic liver injury.

Assessing and Managing Liver Disease

Liver disease in those with HIV is a broad field. Although this chapter touches on the common liver diseases in those with HIV, the reader is referred to other chapters in this book for more detailed information if required. The approach to the assessment of liver disease can be summarized in the following five steps:

200, the pace of injury is probably faster.

200, the pace of injury is probably faster.Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree