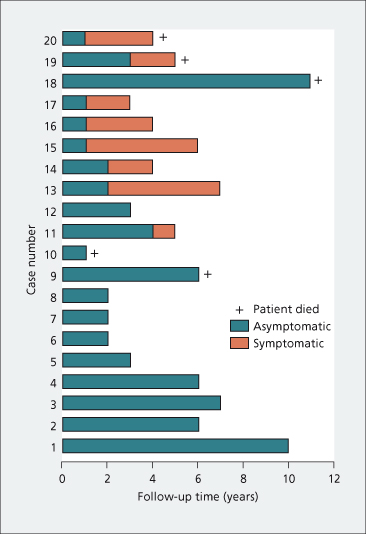

Fig. 15.2. The course of 20 patients with PBC diagnosed when asymptomatic. Note that one patient continued asymptomatic for 10 years [11].

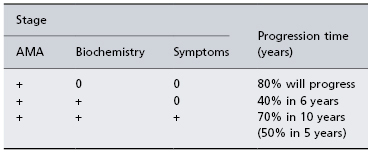

The course of asymptomatic patients is variable but the majority (80%) become symptomatic within 10 years (Table 15.2) and the estimates for developing symptoms in 5 and 20 years are 50 and 95%, respectively [12]. No reliable way has been identified to predict which patients will remain asymptomatic. Some will never become symptomatic and others will run a progressive downhill course (Fig. 15.3).

Table 15.2. The progression of untreated primary biliary cirrhosis [35]

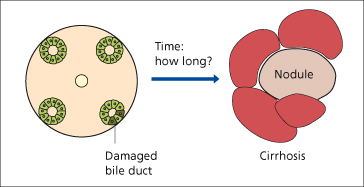

Fig. 15.3. Natural history of PBC: the time taken from acute bile duct damage to end-stage biliary cirrhosis is uncertain [84].

The natural history of histological changes in PBC (without UDCA) has documented that the majority of patients will progress histologically within 2 years. Liver stiffness measurement (transient elastography), a non-invasive test for assessment of liver fibrosis, may be useful to monitor its progression over time [14].

Fatigue is very common, affecting 60% of sufferers [7]. It is the primary predictor of impaired quality of life, which may be assessed by a PBC-specific score [15]. The pathogenesis of fatigue in PBC is unclear but it cannot be explained by depression. Fatigue does not correlate with the liver disease severity and liver transplantation does not improve fatigue. The fatigue phenotype appears to be highly stable in PBC and it’s presence may indicate a poorer prognosis [16,17].

The course is afebrile and abdominal pain is unusual but may persist.

When jaundice is obvious this is complicated by steatorrhoea and consequent weight loss. Skin xanthomas may develop, sometimes acutely, but many patients remain without xanthoma throughout their course. If xanthoma are plentiful, pain in the fingers, especially on opening doors, and in the toes may be due to xanthomatous peripheral neuropathy. There may be a butterfly area over the back which is inaccessible and escapes scratching. These late manifestations of disease are now rarely seen in western countries as liver transplant is performed in most patients before their development.

Osteoporosis in PBC is related to advancing age and disease severity with a possible genetic component and there is a twofold increase in both the absolute and relative fracture risk in people with PBC compared with the general population [18].

Bleeding oesophageal varices may be a presenting feature and rarely before nodules have developed when portal hypertension is related to nodular regenerative hyperplasia. A subgroup of patients with cirrhosis but near normal bilirubin values has a better prognosis than other patients with obvious jaundice. Within a median of 5.6 years, varices have developed in 31% of patients and 48% of these will have bled unless primary prevention manoeuvres have been instituted. Varices are more likely to develop in those with a high serum bilirubin and with an advanced histological stage of the disease. A platelet count of less than 140 000 identifies those patients more likely to benefit from a screening endoscopy [19]. The portohepatic gradient may stabilize or improve with response to ursodeoxycholic acid treatment. Once varices have developed, 83% survive 1 year and 59% 3 years. Survival after the initial bleed is 65% at 1 year and 46% at 3 years.

There is a risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, especially in older males with cirrhosis. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma is recommended is those known to have cirrhosis [20].

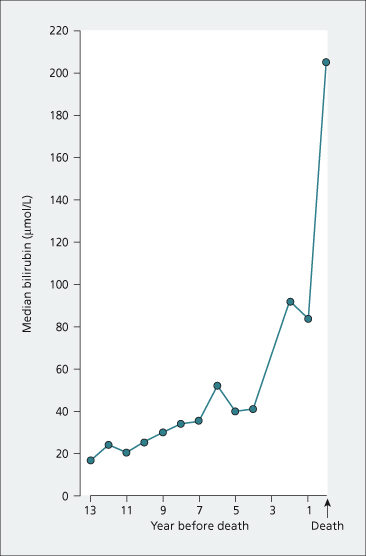

Liver-related mortality has been reported as 60% in symptomatic patients but this will vary according to age at initial diagnosis [8]. If liver transplantation is not an option, the terminal stages last about 1 year and are marked by a rapid deepening of jaundice (Fig. 15.4) with the disappearance of both xanthomas and pruritus. Serum albumin and total cholesterol levels fall. Oedema and ascites develop. The final events include episodes of hepatic encephalopathy with uncontrollable bleeding, usually from the oesophageal varices. An intercurrent infection, sometimes a Gram-negative septicaemia, may be terminal.

Fig. 15.4. The evolution of liver failure in PBC. This nomogram is derived from the medians of pooled serum bilirubin results in patients followed serially from diagnosis to death. Expected survival can be calculated using the Mayo Risk Score which is available online at http://www.mayoclinic.org/gi-rst/mayomodel1.html (accessed 15 Oct. 2010).

Diagnosis

Since the introduction of routine screening of liver biochemical tests many patients are asymptomatic at presentation. Diagnosis is currently based on three criteria: cholestatic liver biochemical tests, presence of serum antimitochondrial antibodies and liver histology that is compatible with PBC. A definite diagnosis requires the presence of all three criteria and a probable diagnosis requires two of these three.

Biochemical Tests

Currently, serum bilirubin values are usually less than 35 µmol/L (2 mg/100 mL) at the time of diagnosis of PBC. Serum alkaline phosphatase and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GT) are raised. The total serum cholesterol is increased but not constantly. The serum albumin level is usually normal at presentation and the serum IgM is usually raised. This is not reliable for diagnosis, although an increase may add some diagnostic weight.

Autoantibodies

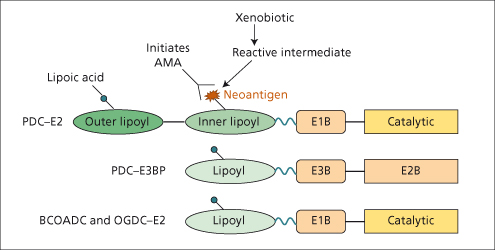

Over 90% of patients have AMA[21]. The antigens to which the antibodies are directed are localized on the inner mitochondrial membrane. The dominant autoantibody response is directed against two components (dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase (E2) and E3-binding protein) of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) [22,23]. The E2 components of the other 2-oxo-acid dehydrogenase complexes also react with AMA [24]. These four mitochondrial autoantigens share a highly conserved structure containing a lipoic acid cofactor (Fig. 15.5). Immunodominant B- and T-cell epitopes have been localized to the inner lipoyl domain of PDC-E2 around the lipoic acid attachment site [25,26].

Fig. 15.5. Schematic representation of the four major mitochondrial autoantigens showing similar domain structure. The essential cofactor, lipoic acid, is covalently attached to a lysine residue in each lipoyl domain. [PDC, pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. E3BP, E3 binding protein. BCOADC, branched chain 2-oxo-acid dehydrogenase complex, OGDC, oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex]. Note xenobiotic incorporation into the inner lipoyl domain of PDC-E2 in place of the cofactor, lipoic acid forming a ‘neoantigen’ [40].

Antinuclear antibodies are found in a minority of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Antinuclear antibodies display unique immunofluorescence patterns such as nuclear dots or a nuclear ring-like pattern. PBC-specific nuclear antigens include a 210-kDa glycoprotein of the nuclear-pore membrane (gp 210), nucleoporin p62 and Sp100, an interferon-inducible nucleoprotein.

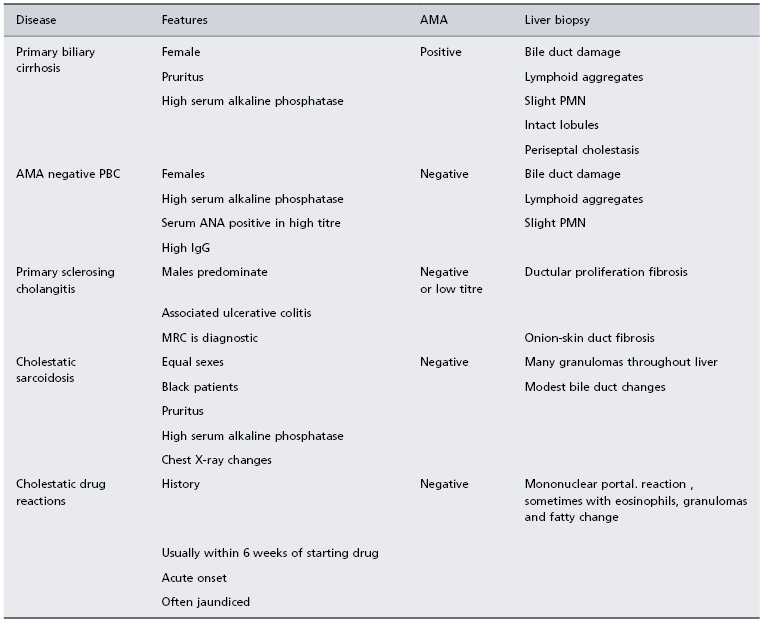

Patients who lack AMA need careful evaluation (Table 15.3).

Table 15.3. Differential diagnosis of primary biliary cirrhosis

ANA, antinuclear antibodies; AMA, antimitochondrial antibodies; PMN, piecemeal necrosis.

They may have AMA-negative PBC, which has been mistakenly termed ‘autoimmune cholangitis’. Clinical presentation, biochemistry, liver histology and response to UDCA are no different from those with typical AMA-positive PBC. Nearly all these patients have PBC-specific antinuclear antibodies. IgM levels are lower.

Visualization of the bile ducts, preferably by MR, is necessary in atypical patients particularly males, those with inconclusive liver biopsy findings or with marked abdominal pain and those who lack AMA. In primary sclerosing cholangitis, cholangiography demonstrates the typical bile duct irregularities.

Idiopathic adult ductopenia is marked by absence of interlobular bile ducts but with minimal portal tract inflammation. The aetiology of ‘vanishing bile syndromes’ are multiple and are sometimes uncertain.

Widespread tissue granulomas may suggest cholestatic sarcoidosis [27]. Liver biopsy shows less bile duct damage than seen in PBC.

Cholestatic drugs reactions are excluded by the history and by the acute onset, with rapidly deepening jaundice developing within weeks of starting the drug.

A small minority of PBC patients may have features of autoimmune hepatitis. This ‘overlap’ syndrome has higher alanine transaminase and IgG levels than are seen in typical PBC and liver biopsy needs to show moderate or severe periportal or periseptal inflammation. Patients with overlap features demonstrate an increased liver-related mortality [28]. Transition between PBC and autoimmune hepatitis may occur [29] associated with biochemical and serological changes and liver biopsy is needed to confirm the new diagnosis.

Liver Biopsy [30]

Many consider liver biopsy to be unnecessary unless the patient tests AMA negative, is at risk of another superimposed liver disease, for example non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, or is a non-responder to treatment with UDCA.

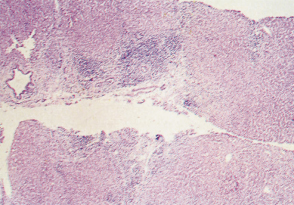

Histologically the only diagnostic lesion is the injured septal or interlobular bile duct. Such ducts may be missed on needle biopsy specimens if the sample contains an inadequate number of portal tracts (≥10 required). They are represented in surgical biopsies (Fig. 15.6).

The disease begins with damage to the epithelium of the small bile ducts. Histometric examinations show that bile ducts less than 70–80 µm in diameter are destroyed, particularly in the early stages. Epithelial cells are swollen, irregular and more eosinophilic. The bile duct lumen is irregular and the basement membrane is disrupted. The bile duct occasionally ruptures. Surrounding the damaged duct is a cellular reaction which includes lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils and histiocytes. Apoptosis of biliary epithelial cells is increased in the presence of inflammation. Granulomas confined to the portal tracts commonly form, usually in zone 1 (Fig. 15.6).

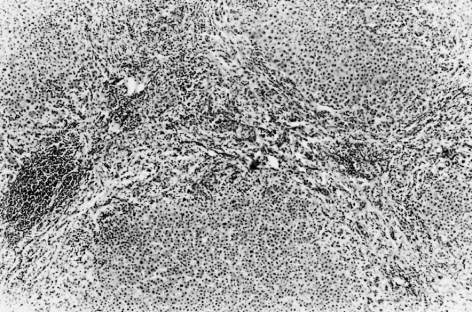

Bile ducts eventually become destroyed. Their sites are marked by aggregates of lymphoid cells, and bile ductules begin to proliferate (Fig. 15.7). Hepatic arterial branches can be identified in zone 1, but without accompanying bile ducts. Fibrosis extends from zone 1 and there is a variable degree of piecemeal necrosis. Piecemeal necrosis is the only histological lesion which significantly enhances the risk of disease progression [31]. Substantial amounts of copper and copper-associated protein can be demonstrated histochemically, due to retention of bile. The fibrous septa gradually distort the architecture of the liver and regeneration nodules form (Figs 15.8, 15.9). These are often irregular in distribution and cirrhosis may be seen in one part of a biopsy but not in another. In the early stages, cholestasis is in zone 1 (portal) but they may be little else seen in terms of diagnostic lesions.

Fig. 15.7. Stage 2 lesion, marked by aggregates of lymphoid cells. Bile ducts begin to proliferate. (H & E, ×10.)

Fig. 15.8. There is scarring and septa contain lymphoid aggregates. Bile ducts are inconspicuous. Hyperplastic ‘regeneration’ nodules are beginning to develop [4]. (H & E, ×48.)

Hepatocellular hyaline deposits, similar to those of alcoholic disease, are found in hepatocytes in about 25% of cases.

The histological appearances have been divided into four stages [32]: stage I, florid bile duct lesions; stage II, ductular proliferation; stage III, scarring (septal fibrosis and bridging); and stage IV, cirrhosis. Such staging is of limited value as the changes in the liver are focal and evolve at different speeds in different parts, hence the stages may overlap. In addition, as PBC is now diagnosed much earlier these stages may not be represented.

Aetiology

The precise aetiology of PBC remains uncertain [33]. The balance of evidence supports an autoimmune process in which autoreactive effector mechanisms are directed at self-epitopes expressed on small-duct biliary epithelial cells [34]. This autoimmune process is thought to be triggered in ‘susceptible’ individuals by exposure to one or more environmental triggers which initiate and/or perpetuate the disease process.

Autoimmune Process

The loss of tolerance to mitochondrial autoantigens is an early event in this progressive disease. AMA are detectable in serum before abnormalities in liver function and long before the onset of symptoms [35]. One hypothesis is that the development of these AMA marks the exposure of a genetically susceptible individual to an initiating environmental factor.

Data exist on effector mechanisms of bile duct destruction. PBC is characterized histologically by autoreactive CD4+ and CD8+T cells surrounding damaged bile ducts. There is a 100-fold increase in autoreactive CD4+ PDC-E2-specific T cells and a 10-fold increase in autoreactive CD8+ T cells in liver infiltrates. CD4+ T cells mature into Th1, Th2, Th17 or T regulatory cell (Treg) phenotypes. Mature Tregs can be reprogrammed and gain the ability to produce interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin-17 (IL-17) and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). The relative proportions of T-cell subpopulations is probably relevant in autoimmunity. It is reported that patients with PBC have fewer circulating Tregs and an increase in the frequency of IL-17+ lymphocytic infiltration in liver tissue [36].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree