- Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) encompasses a spectrum of injury, ranging from fatty liver to frank cirrhosis.

- Although alcoholic fatty liver secondary to excessive alcohol ingestion resolves with abstinence, in those who continue to drink steatosis predisposes to hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis.

- The risk of liver disease increases with the quantity and duration of alcohol intake. The prevalence of alcoholic liver disease is influenced by many factors, including genetic factors (e.g. predilection to alcohol abuse, sex) and environmental factors (e.g. availability of alcohol, social acceptability of alcohol use, concomitant hepatotoxic insults).

- The diagnosis of ALD is based on a combination of features, which include a history of significant alcohol intake, clinical evidence of liver disease, and supporting laboratory abnormalities.

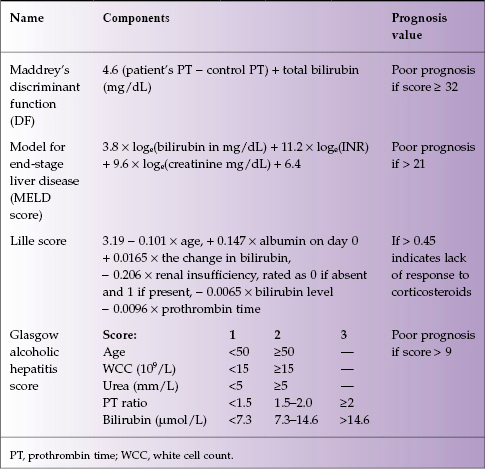

- A variety of scoring systems have been used to assess the severity of alcoholic hepatitis and to guide treatment; Maddrey’s discriminant function, the Glasgow score, and the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score help the clinician decide whether corticosteroids should be initiated, whereas the Lille score is designed to help the clinician decide whether to stop corticosteroids after 1 week of administration.

- Treatment of ALD can be divided into three components: treatment of alcoholism, nutritional support, and specific drug treatments.

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is a general term describing a spectrum of conditions ranging from fatty liver to alcoholic hepatitis to cirrhosis, all of which can be present simultaneously and are potentially reversible with abstinence (with time even remodeling of hepatic fibrosis takes place). Regular alcohol use, even for just a few days, can result in a fatty liver (also called steatosis), a disorder in which hepatocytes contain macrovesicular droplets of triglycerides. Fatty liver develops in about 90% of individuals who drink more than 60 g/day of alcohol, but may also occur in individuals who drink less. Fatty liver is generally reversible with abstinence and is not believed to progress to a chronic form of liver disease if abstinence or moderation is maintained. Alcoholic hepatitis (AH) is an acute form of alcohol-induced liver injury that occurs with the consumption of a large quantity of alcohol over a prolonged period of time; it encompasses a spectrum of severity ranging from asymptomatic derangement of blood tests to fulminant liver failure and death. Cirrhosis involves replacement of the normal hepatic parenchyma with extensive thick bands of fibrous tissue and regenerative nodules, which may result in the clinical manifestations of portal hypertension and liver failure. Hepatic fibrosis occurs in 40–60% of the patients who ingest more than 40–80 g/day for an average of 25 years. This chapter reviews the epidemiology, clinical manifestation, and management of patients with alcohol-induced liver disease.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

The risk of liver disease increases with the quantity and duration of alcohol intake. Although necessary, excessive alcohol use is not sufficient to promote ALD. Only one in five heavy drinkers develops AH, and one in four develops cirrhosis.1

The typical age at presentation of AH is between 40 and 50 years, with the majority occurring before 60. The reasons why only a minority of alcoholics develops hepatitis are incompletely understood. Environmental and host factors that increase the risk of alcoholic cirrhosis are presented in Table 15.1.

Table 15.1 Risk factors associated with alcoholic cirrhosis

| Being female Amount of alcohol ingested Drinking multiple types of alcohol (e.g. beer plus wine, etc.) Alcohol consumption between meals Social acceptability of alcohol use Availability of alcohol Concomitant chronic hepatitis C viral infection Poor nutrition Genetic polymorphisms of genes involved in the metabolism of alcohol (including alcohol dehydrogenase, acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, and the cytochrome P450 system) |

Although women are at increased risk of developing ALD when they drink alcohol, the majority of patients with AH are males because men are twice as likely as women to abuse alcohol.

Different alcoholic beverages contain varying quantities of alcohol (Table 15.2). The risk for developing cirrhosis increases with the ingestion of more than 60–80 g/day of alcohol for 10 or more years in men, and more than 20 g/day in women.2 The amount of alcohol consumption that places an individual at risk of developing AH is not known. However, in practice, most individuals with AH drink more than 100 g/day. The typical patient has drunk heavily for two or more decades, although an occasional patient has abused alcohol for less than 10 years.

Table 15.2 Alcohol contents of beverages

| Type of alcohol | Alcohol content |

| 1 beer (Canadian) | 15 g |

| 4 oz wine | 10 g |

| 1 oz liquor | 10 g |

However, clinical presentation after abstinence for more than 3 months should raise concern for underlying advanced alcoholic cirrhosis or other causes of chronic liver disease. Occasional patients deny alcohol abuse and discreet discussions with family members are required to obtain the true history of the patient’s alcohol use.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

The diagnosis of ALD is based on a combination of features, including a history of significant alcohol intake, clinical evidence of liver disease, and supporting laboratory abnormalities. Fatty liver is usually diagnosed in the asymptomatic patient who is undergoing evaluation for elevated serum aminotransferase levels; typically, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels are less than twice the upper limit of normal and the AST value is greater than that for the alanine aminotransferase (ALT). No laboratory test is diagnostic of fatty liver. Ultrasonographic findings include a hyperechogenic, enlarged liver. Typical histologic findings of fatty liver include fat accumulation in hepatocytes, which is often macrovesicular but it is occasionally microvesicular. The centrilobular region of the hepatic acinus is most commonly affected. In severe fatty liver, however, fat is distributed throughout the acinus. Fatty liver is not specific to alcohol ingestion; it is associated with obesity, insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, malnutrition, and various medications. Attribution of fatty liver to alcohol use therefore requires a detailed and accurate patient history.

Alcoholic hepatitis (AH) is a clinical syndrome of jaundice and liver failure. The typical age at presentation is 40 to 60 years. The clinical and biochemical sign of AH are presented in Table 15.3.

Table 15.3 Manifestations of alcoholic hepatitis

| Clinical manifestations Rapid onset of jaundice Fever Anorexia Ascites Proximal muscle loss Encephalopathy Enlarged and tender liver |

| Biochemical signs Elevated serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase < 300 IU/mL Ratio aspartate aminotransferase alanine aminotransferase > 2 : 1 Elevated white blood cell count (neutrophilia) Elevated total serum bilirubin level (conjugated) Elevated INR |

| Histologic findings Ballooned hepatocytes Mallory bodies Large fat droplets Sinusoidal fibrosis Foamy degeneration of hepatocytes |

The diagnosis of alcoholic cirrhosis rests on finding the classic signs and symptoms of end-stage liver disease in a patient with a history of significant alcohol intake. Patients can present with any or all the complications of portal hypertension, including ascites, variceal bleeding, and hepatic encephalopathy. The histology of end-stage alcoholic cirrhosis, in the absence of acute AH, resembles that of advanced liver disease from many other causes, without any distinct pathologic findings.

Prognosis

The severity of AH can be assessed by calculating Maddrey’s discriminant function,3 the MELD score,4 the Glasgow score,5 and the Lille score6 (Table 15.4). In clinical practice, any of these scoring systems can be used to select patients suitable for pharmacologic therapy. Of note, the Lille score, which is based on pretreatment data plus the response of the serum bilirubin level to a 7-day course of corticosteroid therapy, can be used to determine whether corticosteroids should be discontinued due to the lack of response.6

These various scoring systems are presented in the Table 15.4.

Table 15.4 Various prognosis scoring systems and their components

Treatment

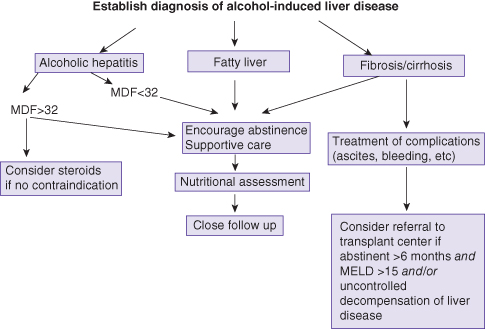

Treatment of ALD can be divided into three components: treatment of alcoholism, nutritional support, and specific drug treatments (Fig. 15.1).

Fig. 15.1 Proposed algorithm for the management of alcohol-induced liver disease. MDF, Maddrey’s discriminant function.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree