Fig. 12.2. Ultrasound scan in acute cholecystitis. Note the thickened wall of the gallbladder (between black and white arrows) with some pericholecystic fluid (single arrow).

Scintigraphy with technetium-labelled iminodiacetic acid derivatives (which track bile flow) also has an accuracy of 95% for acute cholecystitis (non-filling of gallbladder) (Fig. 12.3), but is may be more difficult to arrange quickly, takes longer and involves radioisotope. US takes precedence as the diagnostic approach.

Fig. 12.3. Cholescintigraphy (99mTc Iodida). (a) Normal scan. At 30 min the gallbladder (g) has filled. Isotope has already entered the bowel (B). (b) Acute cholecystitis. Gallbladder has not filled by 60 min.

CT and MRI scanning can show stones, but are most complementary in showing gallbladder size, wall thickness and evidence of inflammation as in acute cholecystitis [1]. They are second-line approaches after US.

Bile Duct

US is also the method of choice in patients with cholestatic features where the primary question is whether there is evidence of bile duct dilatation or disease. The major intrahepatic bile ducts are normally 2 mm in diameter, the common hepatic duct less than 4 mm and the common bile duct less than 5–7 mm. Dilated bile ducts usually (but not always) characterize large bile duct obstruction (Fig. 12.4). US is 95% accurate in diagnosis of bile duct obstruction if the serum bilirubin level exceeds 170 µmol/L (10 mg/dL). False negatives occur if obstruction is of short duration or intermittent. US diagnoses the correct level and cause of obstruction in about 60% and less than 50% of cases, respectively, largely due to failure to visualize the complete biliary tree, particularly the periampullary region. Thus the sensitivity of US for showing common bile duct stones has been reported at 63% [2].

Fig. 12.4. Ultrasound scan showing dilated intrahepatic ducts (arrowed) and common bile duct (marked + +).

CT scanning may follow US, particularly if there is suspicion of malignant disease (see Chapter 13). It is more likely than US to show the level and cause of disease, and conventional CT has been reported to be around 70% sensitive in showing duct stones [2]. Helical CT-cholangiography is more sensitive but involves intravenous contrast and has no advantage over MRCP.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) allows excellent non-invasive cholangiography. Overall, it has an accuracy of greater than 90% in showing common bile duct stones [3] (Fig. 12.5). The sensitivity is lower for stones less than 6 mm in diameter. MRCP also has a high accuracy in showing bile duct strictures and is as sensitive as ERCP in detecting pancreatic carcinoma. It also shows changes of primary sclerosing cholangitis (Fig. 12.6) (see Chapter 16). MRCP is particularly useful in patients who are poor candidates for ERCP such as the elderly with comorbidity.

Fig. 12.5. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in a 39-year-old woman with right upper quadrant discomfort. Ultrasound showed a bile duct of 1 cm but no stones were seen. Gallbladder was normal. Liver function tests were normal apart from marginally abnormal γ-glutamyl transpeptidase. The MRCP shows filling defects in the mid bile duct and stones were removed after endoscopic sphincterotomy.

Fig. 12.6. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in a 40-year-old woman with chronic cholestasis of unknown aetiology. There are dilatations and strictures of the intrahepatic and perihilar bile ducts. Diagnosis: sclerosing cholangitis.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has a sensitivity and accuracy for choledocholithiasis of 96% and 99%, respectively, and is more accurate than transabdominal US [2]. However, the performance of EUS is not statistically better than MRCP [3]. Thus although EUS has been found to be valuable in specific situations, for example the patient with recent acute pancreatitis in whom a stone cannot be seen with non-invasive imaging [4], other techniques come first for most patients. EUS has, however, a role in the evaluation for malignant biliary tract disease (Chapter 13), and in difficult diagnostic situations to help to differentiate between benign and malignant periampullary stricture—with the option of fine needle aspiration cytology or biopsy.

Oral cholecystography (OCG) and intravenous cholangiography have been superseded by other techniques for showing gallbladder stones and bile duct disease. On the rare occasion when it is necessary to show whether patients are appropriate for non-surgical treatment of gallbladder stones, however, OCG is valuable (see below).

Scintigraphy has a limited role for bile duct diseases, but can be valuable to demonstrate a biliary leak, as after cholecystectomy (Fig. 12.7), or non-invasively to document the degree of functional obstruction to intra- or extrahepatic bile ducts.

Fig. 12.7. Cholescintigraphy (99mTc Iodida). Postcholecystectomy bile leak. Isotope tracks laterally from gallbladder bed (short arrow) and T-tube track (long arrow).

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is now widely available (Fig. 12.8). It may be performed in out-patients with only selected patients being admitted afterwards for observation [5].The development of CT, MRI and MRCP, and EUS has led to the majority of ERCPs being planned therapeutic procedures. Sphincterotomy, stone removal, stent insertion, cytological sampling, balloon dilatation and manometry are all feasible. However, ERCP is an invasive procedure and carries the risk of complications. These include pancreatitis (generally ranging between 1 and 7%), cholangitis, bleeding and perforation (after sphincterotomy), as well as the risks of sedation and cardiovascular events in susceptible patients.

Fig. 12.8. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, normal appearances. C, common bile duct; G, gallbladder; PD, pancreatic duct.

The overall complication rate is around 4–7% with a mortality of 0.1–0.4% [6–8]. Complications are related to several factors including the underlying pathology, the difficulty of the procedure and the skill and experience of the operator. One particular focus of discussion currently is around approaches to reduce the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis, particularly with consideration of placement of a temporary pancreatic duct stent in selected high-risk patients [9–11]. A selective rather than global prophylactic antibiotic policy is reported as being equally effective in preventing septic complications [12]. Despite the associated risks, ERCP rather than PTC is usually the first choice for direct cholangiography.

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) is done by passing a fine-gauge needle through the liver under fluoroscopic control and injecting contrast to identify and fill the biliary system (Fig. 12.9). Most PTC procedures are interventional and the biliary system is then entered with a catheter (PT drainage, PTD). Usually this is prior to insertion of an internal/ external biliary drain, or an internal endoprosthesis for malignant disease. However, PTC/D may be used for a combined procedure after failed ERCP access. A wire is passed down the bile duct, through the ampulla and retrieved by the endoscopist. Also, PTD can be done for acute cholangitis when ERCP and drainage has failed.

Fig. 12.9. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogram showing normal right and left intrahepatic ducts and common bile duct, and free flow of contrast into duodenum. The gallbladder is beginning to fill.

PTC, however, carries a potentially greater risk than ERCP since catheters are passed through the vascular liver. Haemorrhage, bile leakage with peritonitis and cholangitis may follow. It is rarely used in patients with benign bile duct disease, unless ERCP has failed or previous surgery (e.g. hepaticojejunostomy) has made the ampulla inaccessible.

The nature of biliary tract disease is such that it presents to general physicians and surgeons as well as hepatologists and hepatobiliary surgeons. Cases are often straightforward, but a multidisciplinary approach with physician, radiologist, pathologist and surgeon is optimal to avoid inappropriate diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

Composition of Gallstones

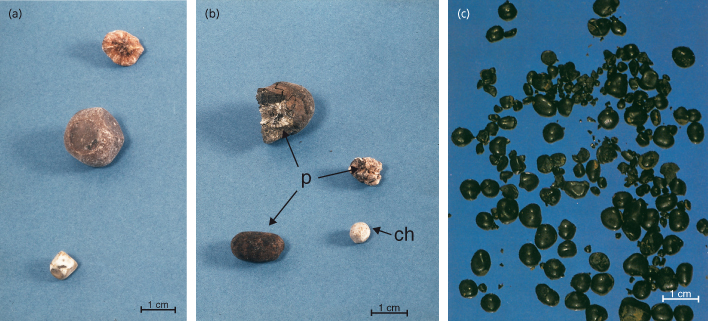

There are three major types of gallstone: cholesterol, black pigment and brown pigment (Fig. 12.10, Table 12.2). In the Western world most are cholesterol stones. Although these consist predominantly of cholesterol (51–99%) they, along with all types, have a complex content and contain a variable proportion of other components including calcium carbonate, phosphate, bilirubinate and palmitate, phospholipids, glycoproteins and mucopolysaccharides. The nature of the nucleus of the stone is uncertain—pigment, glycoprotein and amorphous material have all been suggested.

Table 12.2. Classification of gallstones

Fig. 12.10. (a) Two faceted cholesterol gallstones. The fragment above shows the concentric structure formed as layer upon layer of cholesterol crystals aggregate. (b) Stones removed from the common bile duct (ch, cholesterol gallstone; p, brown pigment stone). (c) Black pigment gallstones.

Formation of Cholesterol Stones

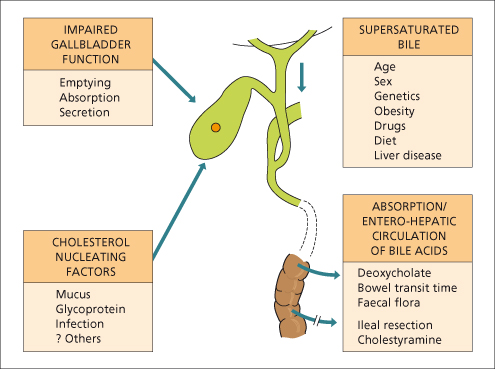

Three major factors determine the formation of cholesterol gallstones. These are: altered composition of hepatic bile, nucleation of cholesterol crystals and impaired gallbladder function (Fig. 12.11).

Fig. 12.11. Major factors in cholesterol gallstone formation are supersaturation of the bile with cholesterol, increased deoxycholate formation and absorption, cholesterol crystal nucleation and impaired gallbladder function.

The complexity is demonstrated by the finding that although cholesterol supersaturation is a prerequisite for gallstone formation, it does not alone explain the pathogenesis. Other factors must be important since bile supersaturated with cholesterol is frequently found in individuals without cholesterol gallstones [13].

Altered Hepatic Bile Composition

Bile is 85–95% water. Other components are cholesterol, phospholipids, bile acids, bilirubin, electrolytes and a range of proteins and mucoproteins.

Cholesterol is insoluble in water. It is secreted from the canalicular membrane in unilamellar phospholipid vesicles (Fig. 12.12). Solubilization of cholesterol in bile depends upon whether there is sufficient bile salt and phospholipid (predominantly phosphatidylcholine (lecithin)) to house the cholesterol in mixed micelles (Fig. 12.13). If there is excess cholesterol or reduced phospholipids and/or bile acid, multilamellar vesicles form and it is from these that there is nucleation of cholesterol crystals and ultimately sludge and stone formation (Fig. 12.12).

Biliary cholesterol concentration is unrelated to serum cholesterol level and depends only to a limited extent on the bile acid pool size and bile acid secretory rate.

Changes in bile acid type also reduce the capacity for cholesterol solubilization. A higher proportion of deoxycholate (a secondary bile acid produced in the intestine and absorbed) is found in gallstone patients. This is a more hydrophobic bile salt and when secreted into bile extracts more cholesterol from the canalicular membrane, increasing cholesterol saturation. It also accelerates cholesterol crystallization.

Cholesterol Nucleation

Nucleation of cholesterol monohydrate crystals from multilamellar vesicles is a crucial step in gallstone formation (Fig. 12.12).

One distinguishing feature between those who form gallstones and those who do not is the ability of the bile to promote or inhibit nucleation of cholesterol. The time taken for this process (‘nucleation time’) is significantly shorter in those with gallstones than in those without and in those with multiple as opposed to solitary stones [14]. Biliary protein concentration is increased in lithogenic bile. Proteins that accelerate nucleation (pronucleators) include gallbladder mucin and immunoglobulin G. Cholesterol gallstones have bilirubin at their centre, and a protein pigment complex might provide the surface for nucleation of cholesterol crystals from gallbladder bile.

Factors that slow nucleation (inhibitors) include apolipoprotein A1 and A2 [15] and a 120-kDa glycoprotein [16]. Ursodeoxycholic acid, as well as decreasing cholesterol saturation, also prolongs the nucleating time [17]. Aspirin reduces mucus biosynthesis by gallbladder mucosa which explains why this drug and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs inhibit gallstone formation [18].

Gallbladder Function

The gallbladder fills with hepatic bile during fasting, concentrates the bile and contracts in response to a meal, resulting in the passage of bile into the duodenum. The gallbladder must be capable of emptying so as to clear itself of microcrystals, sludge and debris that might initiate stone formation.

The concentration of bile salts, bilirubin and cholesterol, for which the gallbladder wall is essentially impermeable, may rise 10-fold or more as water and electrolytes are absorbed. The concentration of these constituents does not, however, rise in parallel and the cholesterol saturation index may decrease with concentration of bile because of the absorption of some cholesterol.

Gallbladder contraction is under cholinergic and hormonal control. Cholecystokinin (CCK), derived from the intestine, contracts and empties the gallbladder and increases mucosal fluid secretion with dilution of gallbladder contents. Atropine reduces the contractile response of the gallbladder to CCK [19]. Other hormones found to have an influence on the gallbladder include motilin (stimulatory) and somatostatin (inhibitory).

Immune processes and inflammation in the gallbladder also appear to effect contraction and promote the production of pronucleators [20].

That gallbladder stasis has a role clinically in the formation of gallstones is suggested by the relationship between impaired gallbladder emptying and the increased incidence of gallstones in patients on long-term parenteral nutrition, and in pregnant women [21].

Biliary Sludge

Biliary sludge is a viscous suspension of a precipitate which includes cholesterol monohydrate crystals, calcium bilirubinate granules and other calcium salts/ sludge. It usually forms as a result of reduced gallbladder motility related to decreased food intake or parenteral nutrition. After formation, sludge disappears in 70% of patients [22]. Twenty per cent of patients develop complications of gallstones or acute cholecystitis. Whether treatment of sludge would reduce the incidence of complications is not known.

Epidemiology [23]

The prevalence of gallstones varies considerably between and within populations studied. However there are broad differences which are consistent. The highest known prevalence is among American Indians with up to 60–70% of females having cholelithiasis or gallbladder disease in some studies. The prevalence in Chilean Indians is also high. The lowest frequencies are in Black Africans (<5%). In the Western world the prevalence of gallbladder stones is about 5–15%, for example in White Americans and in the UK and Italy, around twofold greater in women than in men. Studies suggest a slightly greater prevalence in Norway and Sweden, but lower in China and Japan. The prevalence is likely to rise as lifestyles change.

Factors in Cholesterol Stone Formation

Genetics

Studies have shown genetic risk and have implicated genes, with a clear link to physicochemical changes in cholesterol and phospholipids.

Analysis of mono- and dizygotic twins suggests that genetic factors account for 25% of the difference in the prevalence of gallstones [24]. In an American family study, around 29% of the chance of having symptomatic gallstones was inherited [25].

Candidate gallstone genes have been identified in mouse models, and recent human studies in sib pairs and cohorts identified a common variant (p.D19H) of the hepatocanalicular cholesterol transporter ABCG5/ABG8 to be a risk factor for gallstone formation (sevenfold in homozygotes). This variant appears to contribute up to 11% of the total gallstone risk [26].

In a group of individuals with indicators of a risk of cholesterol stones (and also cholestasis), point mutations in ABCB4 (the transporter for phosphatidyl choline) were found in over 50% of patients [27]. Since ursodeoxycholic acid may reduce the risk in such patients, it has been suggested that checking for mutations in this gene in high-risk patients may be appropriate [28].

Variants in a nuclear receptor (farnesoid X, FXR or NR1H4), which induces ABCB11 and ABCB4, also relate to gallstone formation [29].

Lifestyle

Lack of physical activity [30] is also an association. There also is an association with the metabolic syndrome, and related conditions of obesity, type 2 diabetes and dyslipidaemia [31]. At the molecular level this appears to relate to insulin resistance leading to biliary cholesterol hypersecretion and impaired synthesis of bile acids [32].

Obesity

This seems to be more common among gallstone sufferers than in the general population [33] and is a particular risk factor in women less than 50 years old. Obesity is associated with increased cholesterol synthesis. There are no consistent changes in postprandial gallbladder volume. Fifty per cent of markedly obese patients have gallstones at surgery.

Dieting (2100 kJ/day) can result in biliary sludge and the formation of symptomatic gallstones in obese individuals [34].

Gallstone formation during weight loss following gastric bypass surgery for obesity is prevented by giving ursodeoxycholic acid [35].

Dietary Factors

Epidemiological studies show that chronic over-nutrition with refined carbohydrates and triglycerides increases the risk [36].

Increasing dietary cholesterol increases biliary cholesterol but there is no epidemiological or dietary data to link cholesterol intake with gallstones.

In Western countries, gallstones have been linked to dietary fibre deficiency and a longer intestinal transit time [37]. This increases deoxycholic acid in bile, and renders bile more lithogenic. Deoxycholate is derived from dehydroxylation of cholic acid in the colon by faecal bacteria. There is an enterohepatic circulation. Gallstone patients have significantly prolonged small bowel transit times [38] and increased bacterial dehydroxylating activity in faeces [39].

A diet low in carbohydrate and a shorter overnight fasting period protects against gallstones, as does a moderate alcohol intake in males [40]. Vegetarians get fewer gallstones irrespective of their tendency to be slim [41].

Age

There is a steady increase in gallstone prevalence with advancing years, probably due to the increased cholesterol content in bile. By age 75, around 20% of men and 35% of women in some Western countries have gallstones. Clinical problems present most frequently between the ages of 50 and 70.

Sex and Oestrogens

Gallstones are twice as common in women as in men, and this is particularly so before the age of 50.

The incidence is higher in multiparous than in nulliparous women. Incomplete emptying of the gallbladder in late pregnancy leaves a large residual volume and thus retention of cholesterol crystals. Biliary sludge occurs frequently but is generally asymptomatic and disappears spontaneously after delivery in two-thirds [42]. In the postpartum period gallstones are present in 8–12% of women (nine times that in a matched group) [43]. One-third of those with a functional gallbladder are symptomatic. Small stones disappear spontaneously in 30%.

The bile becomes more lithogenic when women are placed on birth control pills. Women on long-term oral contraceptives have a twofold increased incidence of gallbladder disease over controls [44]. Postmenopausal women taking oestrogen-containing drugs have a significant increase frequency (around 1.8 times) of gallbladder disease [45]. In men given oestrogen for prostatic carcinoma the bile becomes saturated with cholesterol and gallstones may form [46].

Serum Factors

The highest risk of gallstones (both cholesterol and pigment) is associated with low HDL levels and high triglyceride levels, which may be more important than body mass [47]. High serum cholesterol is not a determinant of gallstone risk.

Cirrhosis

About 30% of patients with cirrhosis have gallstones. The risk of developing stones is most strongly associated with Child’s grade C and alcoholic cirrhosis with a yearly incidence of about 5% [48]. The mechanisms are uncertain. All patients with hepatocellular disease show a variable degree of haemolysis. Although bile acid secretion is reduced, the stones are usually of the black pigment type. Phospholipid and cholesterol secretion are also lowered so that the bile is not supersaturated.

Cholecystectomy in patients with cirrhosis carries an increased morbidity and mortality [49,50]. In Child’s group A and B the laparoscopic approach is preferred to open cholecystectomy because of lower morbidity and mortality. In Child C patients and those with a higher MELD score the risk of cholecystectomy is particularly high, making management decisions more difficult [49,50]. In such patients with symptomatic gallbladder and bile duct stones, non-surgical techniques have to be considered as alternatives to surgery.

Infection

Although infection is thought to be of little importance in cholesterol stone formation, bacterial DNA is found in these stones [51]. Conceivably, bacteria might deconjugate bile salts, allowing their absorption and reducing cholesterol solubility.

Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetics have a higher prevalence of gallstones (or a history of cholecystectomy) than non-diabetics, particularly females (42 versus 23%) [52]. The older diabetic tends to be obese, and this may be the important factor in gallstone formation.

Patients with diabetes may have large, poorly contracting and poorly filling gallbladders [53]. A ‘diabetic neurogenic gallbladder’ syndrome has been postulated.

Patients with diabetes mellitus undergoing cholecystectomy, whether emergency or elective, have an increased risk of complications. These are probably related to associated cardiovascular or renal disease and to more advanced age.

Other Factors

Hepatitis C is associated with a higher incidence of gallbladder stones than patients with hepatitis B, or those without hepatitis B or C (11.7 vs. 5.4 vs. 6.0% respectively [54]), but the reason for the link is not known.

Ileal resection breaks the enterohepatic circulation of bile salts, reduces the total bile salt pool and is followed by gallstone formation. The same is found in subtotal or total colectomy [55].

Gastrectomy increases the incidence of gallstones [56].

Long-term cholestyramine therapy increases bile salt loss with a reduced bile acid pool size and gallstone formation.

Parenteral nutrition leads to a dilated, sluggish gallbladder containing stones.

Endoscopic sphincterotomy improves gallbladder emptying and decreases the lithogenicity of bile in patients with gallstone disease [57]. Patients with gallbladder stones have significantly higher sphincter of Oddi tone [58].

Pigment Gallstones

This term is used for stones containing less than 30% cholesterol. There are two types: black and brown (see Table 12.2).

Black pigment stones are largely composed of an insoluble bilirubin pigment polymer mixed with calcium phosphate and carbonate. There is no cholesterol. The mechanism of formation is not well understood, but supersaturation of bile with unconjugated bilirubin, changes in pH and calcium, and overproduction of an organic matrix (glycoprotein) play a role [59]. Overall, 20–30% of gallbladder stones are black. The incidence rises with age. They may pass into the bile duct. Black stones accompany chronic haemolysis, usually hereditary spherocytosis or sickle cell disease, and mechanical prostheses, for example heart valves, in the circulation. They show an increased prevalence with all forms of cirrhosis, particularly alcoholic [48]. Patients with ileal Crohn’s disease may form pigment stones because of increased colonic absorption of bilirubin due to failure of ileal absorption of bile acid [60].

Brown pigment stones contain calcium bilirubinate, calcium palmitate, and stearate, as well as cholesterol. The bilirubinate is polymerized to a lesser extent than in black stones.

Brown stones are rare in the gallbladder. They form in the bile duct and are related to bile stasis and infected bile. They are usually radiolucent. Bacteria are present in more than 90%. Stone formation is related to the deconjugation of bilirubin diglucuronide by bacterial β-glucuronidase [59]. Insoluble unconjugated bilirubinate precipitates.

Brown pigment stones form above biliary strictures in sclerosing cholangitis and in the dilated segments of Caroli’s disease. There is an association with juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula [61]. In Oriental countries, these stones are associated with parasitic infestations of the biliary tract such as Clonorchis sinensis and Ascaris lumbricoides. These stones are frequently intrahepatic.

Natural History of Gallbladder Stones (Fig. 12.14)

Gallstones can be dated from the atmospheric radiocarbon produced by nuclear bomb explosions. This suggests a time lag of about 12 years between initial stone formation and symptoms culminating in cholecystectomy [62].

However, gallbladder stones are usually asymptomatic and diagnosed by chance by imaging or during investigation for some other condition. A small proportion develop symptoms. Around 8–10% of patients with asymptomatic gallstones developed symptoms within 5 years and only 5% required surgery [63,64]. Only about half the patients with symptomatic gallstones come to cholecystectomy within 6 years of diagnosis. Patients with gallstones seem to tolerate their symptoms for long periods of time, preferring this to cholecystectomy. If symptoms develop, they are unlikely to present as an emergency.

Data suggest that elective cholecystectomy is an appropriate choice for patients with biliary colic [65].

Prophylactic cholecystectomy should not be performed for asymptomatic gallbladder stones [66]. It should not be done to prevent gallbladder cancer since the risk is small and less than that of cholecystectomy [67].

Migration of a stone to the neck of the gallbladder causes obstruction of the cystic duct and a rise in gallbladder pressure. There is chemical irritation of the gallbladder mucosa by the retained bile, followed by bacterial invasion. According to the severity of the changes, acute or chronic cholecystitis results. Empyema may follow; perforation, fistula formation and emphysematous cholecystitis are rare.

Migration of a stone into the bile duct may present with pain, jaundice, cholangitis or pancreatitis.

Possible Association of Stones with Gallbladder and Bile Duct Cancer

Population surveys have investigated the link between stones and malignancy of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts.

The relative risk of gallbladder carcinoma is 2.4 if gallbladder stones are 2.0–2.9 cm in diameter, and greater with larger stones [68]. The issue is whether this is causative or an association, meaning that there is a common factor(s) that predisposes to both stones and carcinoma. This remains a possibility [69] and difficult to rule in or out.

There appears to be a lower risk of extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma during follow up of patients who had cholecystectomy, raising the question of a link between gallbladder stones or gallbladders containing stones with extrahepatic bile duct malignant changes [70].

Acute Calculous Cholecystitis

Aetiology

In 95% of patients the cystic duct is obstructed by a gallstone. The imprisoned bile salts have a toxic action on the gallbladder wall. Lipids may penetrate the Rokitansky–Aschoff sinuses and exert an irritant reaction. The rise in pressure compresses blood vessels in the gallbladder wall; infarction and gangrene may follow.

Pancreatic enzymes may also cause acute cholecystitis, presumably by regurgitation into the biliary system when there is a common biliary and pancreatic channel.

Bacterial inflammation is an integral part of acute cholecystitis. Bacterial deconjugation of bile salts may produce toxic bile acids which can injure the mucosa.

Pathology

The gallbladder is usually distended, but after previous inflammation the wall becomes thickened and contracted. There may be vascular adhesions to adjacent structures.

Histology shows haemorrhage and moderate oedema reaching a peak by about the fourth day and diminishing by the seventh day. As the acute reaction subsides it is replaced by fibrosis.

Bacteriology.

Cultures of both gallbladder wall and bile usually show organisms of intestinal type, including anaerobes. Common infecting organisms are Escherichia coli, Streptococcus faecalis and Klebsiella, often in combination. Anaerobes are present, if sought, and are usually found with aerobes. They include Bacteroides and Clostridium sp.

Clinical Features

These vary according to whether there is only mild inflammation or more severe disease such as fulminating gangrene of the gallbladder wall. The acute attack is often an exacerbation of underlying chronic cholecystitis.

The sufferers are often obese, female and over 40, but no type, age or sex is immune.

Pain often occurs late at night or in the early morning, usually in the right upper abdomen or epigastrium and is referred to the angle of the right scapula, to the right shoulder [71], or rarely to the left side. It may simulate angina pectoris.

The pain usually rises to a plateau and can last 30–60 min without relief, unlike the short spasm of biliary colic. Attacks may be precipitated by late-night, heavy meals or fatty food.

Distension pain coming in waves is due to the gallbladder contracting to overcome the blocked cystic duct.

Peritoneal pain is superficial with skin tenderness, hyperaesthesia and muscular rigidity. The fundus of the gallbladder is in apposition to the diaphragmatic peritoneum, which is supplied by the phrenic and last six intercostal nerves. Stimulation of the anterior branches produces right upper quadrant pain and of the posterior cutaneous branch leads to the characteristic right infrascapular pain.

Examination

The patient appears ill. The temperature rises with bacterial invasion. Jaundice usually indicates associated stones in the common bile duct.

The gallbladder is usually impalpable; occasionally a tender mass of gallbladder and adherent omentum may be felt. Murphy’s sign is positive.

The leucocyte count may be raised with a moderate increase in polymorphs. In the febrile patient blood cultures may be positive.

For the patient with acute abdominal pain of uncertain cause, a plain X-ray will be taken during the work-up, but if acute cholecystitis is suspected scanning is indicated. Only about 10% of gallstones are radio-opaque, compared with 90% of renal calculi.

Imaging

The diagnosis of gallbladder disease depends upon scanning because of the overall lack of power of any specific symptom [72]. As described earlier, ultrasound is the test of choice. Scintigraphy is also accurate but second line.

Gallstones cast intense echoes with obvious posterior acoustic shadows (see Fig. 12.1). They change in position with turning of the patient. Stones 3 mm or more in size are usually seen. Diagnostic accuracy is 96% but less experienced operators may not achieve this success.

Acute calculous cholecystitis is suggested by the finding of stones with:

- a thickened gallbladder wall (>5 mm) (see Fig. 12.2);

- a positive sonographic Murphy sign—the presence of maximum tenderness, elicited by direct pressure of the transducer, over a sonographically localized gallbladder;

- gallbladder distension;

- pericholecystic fluid;

- subserosal oedema (without ascites);

- intramural gas;

- a sloughed mucosal membrane.

Cholescintigraphy.

Technetium-labelled iminodiacetic acid derivatives (IDA) are cleared from the plasma by hepatocellular organic anion transport and excreted in the bile (see Fig. 12.3a).

Hepatic IDA scanning may be used to determine patency of the cystic duct in suspected acute cholecystitis. If the gallbladder fails to visualize, despite common bile duct patency and intestinal visualization (Fig. 12.3b), the probability of acute cholecystitis is 80–90%. False-negative results are more common the later the gallbladder fills [73].

CT and MRI scanning are not indicated as the initial assessment of a patient with suspected acute cholecystitis.

Differential Diagnosis

Acute cholecystitis is liable to be confused with other causes of sudden pain and tenderness in the right hypochondrium. Below the diaphragm, acute retrocaecal appendicitis, intestinal obstruction, a perforated peptic ulcer or acute pancreatitis may produce similar clinical features.

Myocardial infarction should always be considered.

Referred pain from muscular and spinal root lesions may cause similar pain.

Prognosis

Spontaneous recovery follows disimpaction of the stone in 85% of patients. Recurrent acute cholecystitis may follow—approximately a 30% chance over the next 3 months [74].

Rarely, acute cholecystitis proceeds rapidly to gangrene or empyema of the gallbladder, fistula formation, hepatic abscesses or even generalized peritonitis. The acute fulminating disease is becoming less common because of earlier antibiotic therapy and more frequent cholecystectomy for recurrent gallbladder symptoms.

Treatment

Medical.

This depends upon the clinical severity for which a grading has been described [75,76]. This is based on the white cell count, clinical findings, duration and features of systemic/ multisystem signs or complications. General measures during the acute phase include intravenous fluids, nothing given orally, analgesia and antibiotics. Tokyo guidelines recommend management depending upon the severity [75,76].

Antibiotic(s) are given if there is clinical evidence of sepsis, and should have a spectrum to cover the likely micro-organisms. Choice is according to hospital policy, but a second or third-generation cephalosporin or combination of a quinolone with metronidazole are usually adequate for the stable patient with pain and mild fever. Patients with features of severe sepsis require broader-spectrum antibiotics such as piperacillin/ tazobactam, combined if necessary with an aminoglycoside. The elderly, and those with diabetes or immunodeficiency, are at particular risk of severe sepsis.

Cholecystectomy (See Below).

For those with mild acute cholecystitis, early cholecystectomy is recommended [75,76]. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials shows that this approach (within 1 week) is superior to delayed cholecystectomy (2 to 3 months later) because of avoidance of gallstone-related complications during the waiting period [65,77]. These could lead to emergency surgery which is known to carry a higher risk than elective operation, particularly in elderly patients over 75 years old and in the diabetic patient where early elective cholecystectomy is preferred once symptoms have developed [78].

For moderate acute cholecystitis there may be early or delayed cholecystectomy, but if early laparoscopic surgery is done, it should be by a highly experienced surgeon so that decisions to alter the approach can be made and carried out if the operation becomes complicated [75,76].

For severe acute cholecystitis, based on the Tokyo guidelines, initial intensive medical treatment with antibiotics is recommended with, if needed, percutaneous cholecystostomy [75,76]; surgical decisions are then customized for individual patients according to the clinical course and degree of surgical risk.

Empyema of the Gallbladder

If the cystic duct remains blocked by a stone and infection sets in, empyema may develop. Symptoms may be of an intra-abdominal abscess (fever, rigors, pain), although the elderly patient may appear relatively well. Treatment is with antibiotics and surgery. There is a high postoperative rate of septic complications [79]. Percutaneous cholecystostomy is considered if the patient is unfit for surgery.

Emphysematous Cholecystitis

The term is used to denote infection of the gallbladder with gas-producing organisms (Escherichia coli, Clostridium welchii) or anaerobic streptococci. The primary lesion is occlusion of the cystic duct or cystic artery. Infection is secondary [80]. The condition classically affects male diabetics who develop features of severe, toxic, acute cholecystitis. An abdominal mass may be palpable.

On a plain abdominal Xray the gallbladder may be seen as a sharply outlined pear-shaped gas shadow. Occasionally air may be seen infiltrating the wall and surrounding tissue. Gas is not apparent in the cystic duct, which is blocked by a gallstone. In the erect position, a fluid level is seen in the gallbladder. However, plain abdominal X-ray may not show the characteristic changes. Ultrasound is diagnostic in around 50% of cases. CT may also show characteristic features.

Standard treatment is with antibiotics and emergency cholecystectomy. In the severely ill patient percutaneous cholecystostomy is an alternative [81].

Chronic Calculous Cholecystitis

This is the commonest type of clinical gallbladder disease. The association of chronic cholecystitis with stones is almost constant. Aetiological factors therefore include all those related to gallstones. The chronic inflammation may follow acute cholecystitis, but usually develops insidiously.

Pathology

The gallbladder is usually contracted with a thickened, sometimes calcified, wall. Stones are seen lying loosely embedded in the wall or in meshes of an organizing fibrotic network. One stone is usually lodged in the neck. Histologically, the wall is thickened and congested with lymphocytic infiltration and occasionally complete destruction of the mucosa.

Clinical Features

Chronic cholecystitis is difficult to diagnose because of the ill-defined symptoms. Episodes of acute cholecystitis punctuate the course.

Abdominal distension or epigastric discomfort, especially after a fatty meal, may be temporarily relieved by belching. Nausea is common, but vomiting is unusual unless there are stones in the common bile duct. Apart from a constant dull ache in the right hypochondrium and epigastrium, pain may be experienced in the right scapular region, substernally or at the right shoulder. Postprandial pain may be relieved by alkalis.

Local tenderness over the gallbladder and a positive Murphy sign are very suggestive.

Investigations

The temperature, leucocyte count, haemoglobin and erythrocyte sedimentation rate are within normal limits. A plain abdominal X-ray may show calcified gallstones. However, the imaging technique of first choice is ultrasound, which may show gallstones within a fibrosed gallbladder with a thickened wall. Non-visualization of the gallbladder is also a significant finding. CT scan may show gallstones but this technique is not usually appropriate in the diagnostic work-up. Endoscopy may be necessary to rule out gastric or duodenal inflammation or ulceration.

Differential Diagnosis

Fat intolerance, flatulence and postprandial discomfort are common symptoms. Even if associated with imaging evidence of gallstones, the calculi are not necessarily responsible since stones are frequently present in the symptom-free.

Other disorders producing a similar clinical picture must be excluded before cholecystectomy is advised, otherwise symptoms persist postoperatively. These include peptic ulceration or inflammation, hiatus hernia, irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsias.

Since approximately 10% of young to middle-aged adults have gallstones, symptomatic gallbladder disease may be over-diagnosed. Conversely, ultrasound is only about 95% accurate and symptomatic gallbladder disease may therefore sometimes be unrecognized.

Prognosis

This chronic disease is compatible with good life expectancy. However, once symptoms, particularly biliary colic, are experienced, the patients tend to remain symptomatic with about a 40% chance of recurrence within 2 years [82]. Gallbladder cancer is a rare, later development (see above).

Treatment

Medical measures may be tried if the diagnosis is uncertain and a period of observation is desirable. This is especially so when indefinite symptoms are associated with a well-functioning gallbladder. The general condition of the patient may contraindicate surgery. The infrequent place of medical dissolution and shock-wave lithotripsy of radiolucent stones is discussed later.

Obesity should be addressed. A low-fat diet is advisable.

If the patient is symptomatic, particularly with repeated episodes of pain, cholecystectomy (see below) is indicated.

Acalculous Cholecystitis

Acute

About 5–10% of acute cholecystitis in adults and about 30% in children occurs in the absence of stones. The most frequent predisposing cause is an associated critical condition such as after major non-biliary surgery, multiple injuries, major burns, recent childbirth, severe sepsis, mechanical ventilation and parenteral nutrition.

The pathogenesis is unclear and probably multifactorial, but bile stasis (lack of gallbladder contraction), increased bile viscosity and lithogenicity, and gallbladder ischaemia are thought to play a role. Administration of opiates, which increase sphincter of Oddi tone, may also reduce gallbladder emptying.

Clinical features should be those of acute calculous cholecystitis with fever, leucocytosis and right upper quadrant pain but diagnosis is often difficult because of the overall clinical state of the patient who may be intubated, ventilated and receiving narcotic analgesics.

There may be laboratory features of cholestasis with a raised bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase. Ultrasound and CT are complementary and useful in showing a thickened gallbladder wall (>5mm), pericholecystic fluid or subserosal oedema (without ascites), intramural gas or a sloughed mucosal membrane. The sensitivity of ultrasound varies widely between studies (30–100%), but prospective studies have suggested that this is a useful technique [83,84].Cholescintigraphy is reported to have a sensitivity of 60–90% for acalculous cholecystitis [85,86], but moving patients to the imaging unit for the time required for scanning may not be practical.

Because of the difficulties of diagnosis a high index of suspicion is needed, particularly in patients at risk. Gangrene and perforation of the gallbladder are common. The mortality is high, 41% in one series [85], often due to delayed diagnosis.

Treatment is emergency cholecystectomy. In the critically ill patient percutaneous cholecystostomy under ultrasound guidance may be life saving (see below).

Chronic (Including Gallbladder Dyskinesia)

This is a difficult diagnosis as the clinical condition resembles others, particularly irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsias. A description of biliary-like pain has been endorsed by the Rome committee on functional biliary and pancreatic disorders [87]: an episodic, severe, constant pain, in epigastrium or right upper quadrant, lasting at least 30 min, severe enough to interrupt daily activities or lead to consultation with a physician. Laboratory investigations (liver enzymes, conjugated bilirubin, amylase, lipase) are normal; routine transabdominal ultrasound scan shows a normal gallbladder.

Cholescintigraphy with measurement of the gallbladder ejection fraction 15 min after CCK infusion has been used to try and identify patients who have putative gallbladder pathology and would benefit from cholecystectomy. Normal individuals have an ejection fraction of around 70%. In those with a low ejection fraction (usually regarded as less than 35–40%) or who develop pain during the infusion, symptom relief after cholecystectomy is reported in between 70 and 90% of patients [88–90]. However, decisions on management based on the results of a single isotope scan alone may not appear appropriate. There are many issues regarding the actual technique used (e.g. dose and rate of CCK infusion) and that a low ejection fraction is not specific for functional gallbladder disease [91]. Results of scanning should be taken in the context of the other clinical features of the patient. Of note is that EUS may detect small gallbladder stones missed by transabdominal US and in these patients cholecystectomy resulted in loss of pain [92].

In patients with acalculous gallbladder disease undergoing cholecystectomy, chronic cholecystitis, cholesterolosis, muscle hypertrophy and/or a narrowed cystic duct have been shown in patients in whom symptoms were relieved [89,90].

Cholecystectomy

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, introduced in the late 1980s, is the current standard treatment for symptomatic gallbladder stones, and mild and moderate acute cholecystitis, based on superior outcomes compared with open cholecystectomy [93–95]. Open cholecystectomy is still required where the laparoscopic approach fails, or is not possible. Thus expertise is still needed for the open operation.

Operative Approach for Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

Under general anaesthesia the abdominal cavity is insufflated with CO2 and the laparoscope and operating channels inserted. Cystic duct and vessels to the gallbladder are carefully identified and clipped. Haemostasis is achieved by electrocautery or laser. The gallbladder is dissected from the gallbladder bed on the liver and removed whole. When necessary large stones are fragmented while they are still within the gallbladder to allow its delivery through the anterior abdominal wall.

Results

Systemic reviews and meta-analyses show that there is no overall difference in outcome measures of mortality and complications between open, small-incision and laparoscopic cholecystectomy [93,96]. However, the minimally invasive methods (laparoscopic and small incision) were associated with a significantly shorter postoperative hospital stay (around 3 days) compared with open cholecystectomy, and convalescence was shortened (around 22 days). The results from laparoscopic and small incision cholecystectomy were similar. The smaller incision approach interestingly had a shorter operative time and possible lower cost than laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

The Cochrane review raises the question of why laparoscopic rather than mini-incision cholecystectomy has become the standard approach for patients with symptomatic disease, and suggests that to address this other outcomes need more concerted analysis, such as symptom relief and complications. One study involving minilaparotomy and laparoscopic cholecystectomy evaluated pain scores, physical function and psychological health 1 week after operation and found that the laparoscopic approach gave a significantly better outcome [97] (Fig. 12.15). The wide use of laparoscopic cholecystectomy also appears to reflect patient preference and the overall pattern of practice available. Thus practitioners of mini-incision surgery are in the minority, because of its technical difficulty and the fewer opportunities for training.

Fig. 12.15. Laparoscopic versus minicholecystectomy. (a) Postoperative hospital stay. (b) Return to work in the home.

(From [97] with permission.)

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is successful in about 95% of patients. In the remainder, the operation has to be converted to open cholecystectomy. This is more likely if there is acute cholecystitis, particularly with empyema [98]. In these cases, initial laparoscopic assessment is appropriate and conversion to open operation made if indicated. In experienced hands laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute and gangrenous cholecystitis is as safe and effective as open cholecystectomy although there is a moderately high conversion rate (16%) to the open procedure [99].

Complications

The perioperative mortality lies between 0 and 0.3% [65,96]. The complication rate is around 5% [96], and includes bile duct injury, biliary leak, postoperative bleeding and wound infection. Complication rates have been reported to be associated with patient characteristics (age, comorbidities) rather than surgeon or hospital operative volume [100]. Bile duct injury occurs in around 0.4–0.6% of patients [101,102], and this is considered as being higher than in the era of open cholecystectomy (0.2–0.3%)[101]. This emphasizes the need for caution at surgery and for rigorous training. Duct injury may occur even with an experienced surgeon.

The reported risks of open cholecystectomy (collected recently) are now greater than laparoscopic, but this predominantly reflects the patient characteristics of those chosen for open operation preoperatively, and those converted from laparoscopic to open at the time of surgery. Thus differences in 30-day morbidity (18.7 % vs. 4.8%; open versus laparoscopic respectively) and 30-day mortality (2.4% vs. 0.4%) reflect these patient factors, including ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) class, patient comorbidities, functional status, age, previous abdominal surgery, emergency status and albumin [103].

Cholangiography

Of patients having cholecystectomy, 10–15% have common duct stones. Preoperative ERCP is appropriate for patients with criteria suggestive of a duct stone—recent jaundice, cholangitis, pancreatitis, abnormal liver function tests or duct dilatation on ultrasound. If the data raise the question of a duct stone but are not considered enough for ERCP, MRCP is indicated. If there is a duct stone it is removed after sphincterotomy.

Intraoperative cholangiography at laparoscopic cholecystectomy needs experience. Some advocate its routine use to define bile duct anatomy, anomalies and stones, but this prevents only the minority of bile duct injuries [104].

Laparoscopic Common Bile Duct Exploration

In experienced hands duct stones can be removed in 90% of patients [105]. However, this technique is not routine because of lack of expertise and the need for special equipment. Laparoscopic removal of common duct stones is as effective and safe as endoscopic sphincterotomy [106]. Management should be customized according to local expertise, resources and patient considerations.

Percutaneous Cholecystostomy

This has a particular place in the elderly patient with acute complicated cholecystitis with comorbid disease [107]. The method can either be done under ultrasound control or fluoroscopy after initial opacification using a skinny needle. A drainage catheter can be left to drain the gallbladder, or aspiration of the fluid and pus can be done without continued drainage [108]. Both methods are combined with intensive antibiotic therapy. Bile/ pus is sent for culture. There is usually rapid relief of clinical symptoms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree