Chapter 15 VOIDING DYSFUNCTION AFTER PELVIC SURGERY

Pelvic surgery can result in urinary retention or other voiding dysfunction by causing inadvertent damage to the pelvic plexus. It occurs most often after abdominoperineal resection and radical hysterectomy, although it may be seen after transvaginal or abdominal surgery for urinary incontinence (e.g., colposuspension, use of tension-free vaginal tape [TVT]) and pelvic organ prolapse, hysterectomy for benign disease, and laparoscopic hysterectomy.

SURGICAL ANATOMY OF THE PELVIC NERVOUS SYSTEM

The primary supply to the detrusor is by parasympathetic nerves that are uniformly and diffusely distributed throughout the detrusor. In contrast, the sympathetic nerve supply to the detrusor is rather sparse.1 In women, numerous parasympathetic nerves, identical to those innervating the detrusor, supply the bladder neck and urethral muscle. The female bladder muscle and urethra receive a poor supply of sympathetic innervation.2 The sympathetic preganglionic nuclei are located in the L1 and L2 spinal segments and possibly in the T12 segment. Afferent sensory fibers from the bladder exit along the sympathetic or parasympathetic pathways.

The superior hypogastric plexus is a fenestrated network of fibers anterior to the lower abdominal aorta. The hypogastric nerves exit bilaterally at the inferior poles of the superior hypogastric plexus that lie at the level of the sacral promontory. The network of nerve structures is located between the endopelvic fascia and the peritoneum. The hypogastric nerves unite the superior hypogastric plexus and the inferior hypogastric plexus or pelvic plexus bilaterally. The inferior hypogastric plexus has connections with the sacral roots from S3 and some contributions from S4 and S2.3 The superior hypogastric plexus and hypogastric nerves are mainly sympathetic, the pelvic splanchnic nerves are mainly parasympathetic, and the inferior hypogastric plexus contains both types of fibers.

Ablative pelvic surgery may result in injury to the pelvic plexus and pudendal nerve, leading to abnormal function of parasympathetic, sympathetic, and somatic function. The resultant urodynamic abnormalities include any combination of reduced compliance, hypocontractile detrusor, bladder neck incompetence identified on fluoroscopic screening, reduced urethral closure pressure, and electromyographic changes in the perineal musculature.4–6

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF VOIDING DYSFUNCTION

Failure to store may be caused by detrusor overactivity, which may result from denervation supersensitivity after pelvic dissection or from surgery-related bladder outlet obstruction (e.g., after tight suburethral slingplasty). Bladder outlet obstruction may be the most common factor in the development of postoperative voiding dysfunction.7 Bladder outlet obstruction is intimately involved with the onset of postoperative voiding dysfunction. Harrison and associates8 and Speakman and colleagues9 proposed that parasympathetic denervation supersensitivity develops as a result of bladder outlet obstruction, and others10 have postulated that denervation hypersensitivity may develop from the surgical dissection alone in the absence of bladder outlet obstruction. Other studies suggested that bladder outlet obstruction might result in changes in cholinergic and purinergic signaling. Likewise, inadequate tension during sling placement, although uncommon, may result in failure of the bladder to store.

Bladder outlet obstruction after sling surgery is related to increased tension resulting in urethral compression.7 It may result from different causes after different procedures for incontinence. Retropubic and transvaginal needle suspensions stabilize lateral juxtaurethral tissues; obstruction is often related to hyperelevation of the bladder neck and kinking of the proximal urethra. Pubovaginal slings provide suburethral support to augment urethral coaptation during periods of increased intra-abdominal pressure. Midurethral slings using TVT (Gynecare, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) or SPARC mesh material (American Medical Systems, Minnetonka, MN) are the new class of antiincontinence procedures and are placed without tension at the mid-urethral level to simulate the supportive function of the pubourethral ligaments. Obstruction after these procedures has been attributed to compression from excessive tension or sling misplacement or migration.7

Voiding with a weak detrusor contraction (identified by cystometrogram) or during a Valsalva maneuver has been associated with a higher risk of urinary retention and surgical failure.11–13 Miller and colleagues11 observed that of 21 women who voided without contraction on the preoperative test, 4 (19%) presented with postoperative urinary retention, compared with none of 48 other women with normal contraction. In the same study, no patient with a contraction pressure greater than 12 cm H2O presented with retention. Among the parameters tested for voiding dysfunction, only PVR volume was a significant factor. However, the investigators emphasized that the small sample limited the conclusions of the study.11

EVALUATION OF VOIDING DYSFUNCTION

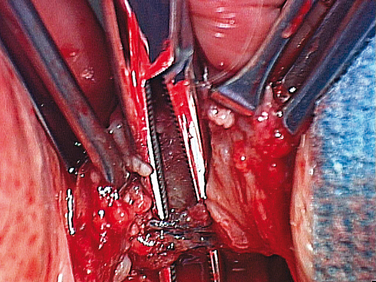

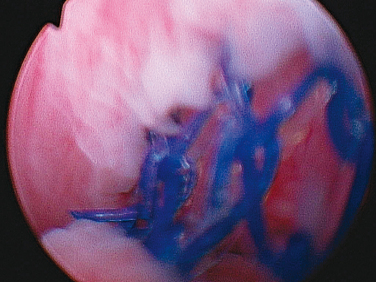

Studies have found that patients with poor detrusor contractility and those who void with abdominal straining may require a longer period of postoperative catheterization (e.g., after retropubic suspensions and pubovaginal sling) and take longer to resume normal voiding.14,15 However, McLennan and coworkers16 found no association between returning to normal voiding and length of postoperative catheterization in those undergoing autologous fascia lata sling surgery. Urethral erosion (Fig. 15-1) and bladder perforation (Fig. 15-2) during placement of a synthetic sling should be excluded by a thorough cystourethroscopy (if necessary, by a retroflexed flexible cystoscope) during the evaluation of a patient with urgency, urge incontinence, UTI, and or hematuria after slingplasty.

History and Physical Examination

The findings on physical examination may vary from normal to a frankly hypersuspended urethra. Midurethral slings (e.g., SPARC suburethral sling, TVT) typically do not result in overcorrection of the urethrovesical angle.17 Bladder neck slings, however, can pull or scar the urethra against the pubic bone and result in a negative urethrovesical angle. The surgeon may also encounter an iatrogenic obstruction without hypersuspension or elevation of the bladder neck or urethra. Any additional outlet resistance may be enough to cause retention or de novo obstruction in patients with a hypocontractile detrusor.

Video Urodynamic Study

Although commonly performed by most clinicians, the evidence-based value of urodynamic study in the evaluation of voiding dysfunction after incontinence surgery remains controversial. Most studies have shown a poor correlation between findings on urodynamics and outcomes after urethrolysis.17

Urodynamic studies may provide information on detrusor overactivity or impaired compliance in patients in urinary retention or increased PVR capacity.18 They may also confirm the diagnosis of obstruction as demonstrated by high pressure or low flow. McGuire and colleagues,19 Nitti and coworkers,20 and Cross and associates21 have shown that presence of an adequate detrusor contraction has no association with successful voiding after transvaginal urethrolysis and sling takedown. Urodynamic study may provide a specific diagnosis of voiding dysfunction (e.g., impaired pelvic floor relaxation during voiding) and therefore can be helpful in directing therapy. It may also ascertain the cause of concomitant incontinence, guiding concurrent surgery during urethrolysis.

Absolute urodynamic criteria for obstruction in women have not been defined despite several proposed cutoff values. Chassagne and associates22 noticed that at a cutoff value of 15 mL/sec or less, flow with a combined detrusor pressure of at least 20 cm H2O was able to define bladder outlet obstruction in women with a sensitivity of 74% and specificity of 91%. Blaivas and Groutz23 used a “free uroflow” parameter in 600 women to provide useful information for those unable to void during the study. They classified obstruction on the basis of a detrusor pressure of more than 20 cm H2O despite no flow or an inability to void with a catheter in place. Nitti and coworkers24 used a combination of multichannel urodynamic study and videofluoroscopy to aid in the diagnosis of bladder outlet obstruction as a sustained detrusor contraction with reduced flow and radiographic evidence of obstruction between the bladder neck and urethra. However, if a patient does not demonstrate a contraction during the voiding phase with concomitant uroflow, it is not as useful. Notwithstanding these limitations, a urodynamic study confirming obstruction can make the surgeon feel more confident in his or her decision to perform urethrolysis. Urodynamic study provides information regarding bladder capacity, SUI, compliance, detrusor overactivity, or learned voiding dysfunction.

Cystoscopy

All patients with persistent storage symptoms after pelvic surgery should undergo cystoscopy to rule out urethral erosion (see Fig. 15-1) and bladder perforation (see Fig. 15-2) from sutures, the suture passer, or sling material. Cystoscopy may also show a hypersuspended mid-urethra or bladder neck (indicating excessive sling tension), scarring, deviation of the urethra, misplacement or migration, or even a fistula. Vaginoscopy also can be performed to exclude vaginal erosion of a sling.

Postoperative Recovery

Some delay in initiating volitional voiding may occur up to 4 weeks after any anti-incontinence surgery. Management depends on the nature of symptoms. Those with high PVR volumes or complete retention should be initially treated with intermittent or continuous catheterization for up to 3 or 4 weeks. The clinician can use his or her judgment to intervene sooner. Significant incomplete emptying or total retention persisting beyond this period rarely resolves without intervention. Evaluation and treatment can therefore be considered at this point. Experience with midurethral polypropylene slings suggests that incomplete emptying or urinary retention can be addressed as early as 1 week postoperatively.25 However, the outcomes after earlier intervention have not been established. In patients with voiding symptoms alone, a temporal relationship of severe symptoms after surgery, and normal preoperative voiding and emptying, urethrolysis may be undertaken without urodynamic assessment. This principle also applies to obstruction after any incontinence procedure when a temporal or causal relationship between surgery and voiding dysfunction exists.

Evaluation in those with de novo or worsening storage symptoms and normal emptying is based on the severity of bother compared with that from preoperative symptoms. Such patients should initially undergo conservative treatment with fluid restriction and antimuscarinic agents. If symptoms persist, urodynamic study and cystoscopy should be performed. If symptoms fail to resolve over an arbitrary 3 months’ waiting period and obstruction is the cause of the storage symptoms, urethrolysis should be considered. Although 3 months is the minimal period before surgical intervention in most urethrolysis series,26 we feel that treatment should be individualized for each patient with storage symptoms after pelvic organ prolapse or sling surgery.

PELVIC SURGERY

Radical Hysterectomy

Short-term and long-term bladder dysfunction remains a common side effect after radical hysterectomy, with bladder atony (requiring indwelling catheter drainage for more than 2 weeks) reported in as many as 42% of patients.27 Mundy and colleagues28 reported voiding dysfunction in 52% to 85% of patients after radical total hysterectomy.

Mundy and colleagues28 reported urinary retention in only 0.5% of patients after radical hysterectomy, whereas straining was required by 85%. Buchsbaum and associates29 reported urinary retention in 10% to 60% of patients after radical hysterectomy. Compared with surgery, adjuvant pelvic irradiation is more often associated with contracted and overactive bladders. Retention is usually treated with clean intermittent selfcatheterization. Bandy and assocaites30 have shown that prolonged indwelling catheterization (>30 days) after radical hysterectomy is associated with worse long-term PVR and total bladder capacity. Fortunately, this voiding dysfunction becomes permanent in less than 5% of patients.30

In a prospective study of 18 patients who underwent modified radical hysterectomy (involving restricted dissection of the anterior parts of the cardinal ligament and preservation of the posterior cardinal ligament), Chuang and coworkers31 demonstrated only temporary (<6 months) vesicourethral dysfunction attributable to transient somatic and autonomic demyelination with or without denervation. These investigators studied the patients by pudendal motor nerve conduction and urodynamic studies, including urethral pressure profiling, cystometry, and uroflowmetry.

Central Compartment Surgery and Voiding Dysfunction

Hysterectomy for Benign Disease

Urologic complications occur after 0.1% of the abdominal and 0.05% of the vaginal procedures.32 Most controlled, prospective studies have found minimal effect of hysterectomy for benign disease on bladder function, and urinary retention therefore appears to be related to other factors.33 Voiding dysfunction is more common after total than after subtotal hysterectomy performed for benign causes (see Fig. 15-1).34

Loss of bladder-filling sensation is the suggested pathophysiologic mechanism of urinary retention after hysterectomy.35 Everaert and colleagues35 showed that urinary retention after hysterectomy for benign disease was associated with deafferentiation of the bladder wall in four patients and of the bladder neck in one. Decreased visceral sensation of the bladder or bladder neck is associated with neurogenic disease.36 Functionally, these patients have absent filling sensation on cystometry, together with partial or complete sensory denervation of the bladder, resulting in increased bladder capacity and secondary urinary retention. Compared with subtotal hysterectomy, total hysterectomy has been associated with a more prominent decrease in voiding frequency and increased bladder capacity.34 Mild symptoms of deafferentiation are more frequent after hysterectomy but are temporary.33

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree