Vascular Isolation and Techniques of Vascular Reconstruction

Ian McGilvray

Alan W. Hemming

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONSHepatobiliary surgical and liver preservation techniques have evolved to the point that the reconstruction of critical hepatic vasculature can be performed with acceptable morbidity and mortality. As a result, the indications for surgery on tumor involving the hepatocaval confluence, inferior vena cava, and/or portal vessels are expanding—this is particularly true in centers that have a strong background in both hepatobiliary oncology and liver transplantation. The techniques described in this chapter are generally applicable to cases where the local aggression of the tumor involved—as it relates to vascular structures such as the cava and hepatic veins—does not preclude long-term survival. Examples of this concept include intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas that are confined to the liver with no lymph node extension but invasion or encasement of major vascular structures in the liver, sarcomas that invade or impinge on major hepatic vascular structures, and selected cases of metastatic colon cancer or hepatocellular carcinoma. Whatever the diagnosis, careful patient selection is of paramount importance to ensure that the possible benefits outweigh the risks: these cases should always be approached in the context of multidisciplinary oncologic care.

The liver receives a dual vascular inflow of approximately 1500 ml/min. The portal vein provides three quarters of total hepatic blood flow while the hepatic artery provides the remaining 25%. This inflow is directed into the liver and subsequently the hepatic sinusoids. Outflow from the sinusoids is via the terminal hepatic venules, which subsequently coalesce into larger branches of the hepatic veins and then the major hepatic vein branches subsequently empty into the inferior vena cava.

During liver surgery, the hepatic parenchyma must be divided and measures to control the 1500 ml/min of blood flow through the liver must be used to minimize bleeding. The great majority of liver resections can be performed using standard techniques that control blood loss and minimize hepatocellular injury (see Chapter 18). Standard techniques include maintaining a low central venous pressure to minimize bleeding from small hepatic veins and meticulous ligation or control of small intrahepatic vessels while

maintaining hepatic perfusion. However, there are instances which may require varying degrees of hepatic vascular inflow and outflow control to avoid major hemorrhage. In standard liver resection, even without vascular involvement, it may be beneficial to perform pedicle clamping (Pringle’s maneuver) to reduce bleeding from the cut surface of the liver during transection. Pringle’s maneuver has been shown to be tolerated best when applied intermittently, with 15 minute clamp periods interspersed with 5 minute periods of perfusion. Alternatively a period of ischemic preconditioning of the liver using a short period of clamping followed by a more prolonged clamp application of up to one hour has been shown to attenuate ischemia reperfusion injury. There are few contraindications to using hepatic inflow occlusion, or pedicle clamping during most liver surgery. In patients that have an injured liver due to biliary obstruction, chemotherapy, or steatosis, it may be wise to avoid inflow occlusion but should be used if bleeding is excessive.

maintaining hepatic perfusion. However, there are instances which may require varying degrees of hepatic vascular inflow and outflow control to avoid major hemorrhage. In standard liver resection, even without vascular involvement, it may be beneficial to perform pedicle clamping (Pringle’s maneuver) to reduce bleeding from the cut surface of the liver during transection. Pringle’s maneuver has been shown to be tolerated best when applied intermittently, with 15 minute clamp periods interspersed with 5 minute periods of perfusion. Alternatively a period of ischemic preconditioning of the liver using a short period of clamping followed by a more prolonged clamp application of up to one hour has been shown to attenuate ischemia reperfusion injury. There are few contraindications to using hepatic inflow occlusion, or pedicle clamping during most liver surgery. In patients that have an injured liver due to biliary obstruction, chemotherapy, or steatosis, it may be wise to avoid inflow occlusion but should be used if bleeding is excessive.

Cases that involve major vascular structures that require resection and reconstruction will need additional vascular control. If possible, the surgeon can take advantage of the dual blood supply to the liver (arterial and portal) and clamp one source while maintaining the other. For example, if only the portal vein needs to be resected and reconstructed, proximal and distal control of the vein can generally be achieved while maintaining arterial flow to the liver, thus avoiding prolonged ischemia. If hepatic arterial involvement requires resection and reconstruction portal venous flow can be maintained and hepatic ischemia is minimized.

Tumors that involve or are in close proximity to the inferior vena cava or confluence of the hepatic veins may require total vascular isolation of the liver, with control of both vascular inflow and outflow. Depending on the complexity of the vascular reconstruction that is to be performed, it may be necessary to increase the acceptable period of hepatic ischemia by using cold perfusion techniques, whether in situ, or ex vivo. Historically, complete vascular isolation has not been as well tolerated by the liver or the patient as simple inflow occlusion, and major vascular reconstruction during liver surgery has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Patients with any significant comorbidity, including even mild renal dysfunction are likely poor candidates for hepatic resection with vascular reconstruction. This chapter will focus on techniques involved in resecting and reconstructing the IVC and hepatic veins.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

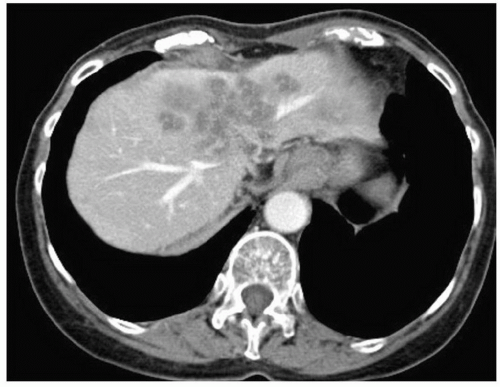

PREOPERATIVE PLANNINGAs with all liver resectional surgery for malignancy, complete staging of the tumor is required. This includes both imaging of the liver and staging of any extrahepatic disease (see Chapter 18). More recently both CT (Fig. 30.1) and MRI (Fig. 30.2) have allowed volumetric assessment of the projected liver remnant. In standard liver resections a

future liver remnant volume of 25% or more of total liver volume is acceptable for proceeding to resection. In cases where major vascular reconstruction is being considered we have chosen—somewhat arbitrarily—a projected liver remnant of less than 40% as an indication for preoperative portal vein embolization of the side of the liver to be resected. This recommendation is based on what is required for performing resections in the injured or cirrhotic liver. While there is no prospective data to indicate an absolute requirement, there seems little down side to providing an additional margin of safety in complex hepatic operations that require vascular reconstruction.

future liver remnant volume of 25% or more of total liver volume is acceptable for proceeding to resection. In cases where major vascular reconstruction is being considered we have chosen—somewhat arbitrarily—a projected liver remnant of less than 40% as an indication for preoperative portal vein embolization of the side of the liver to be resected. This recommendation is based on what is required for performing resections in the injured or cirrhotic liver. While there is no prospective data to indicate an absolute requirement, there seems little down side to providing an additional margin of safety in complex hepatic operations that require vascular reconstruction.

Figure 30.2 MRI demonstrating metastatic colorectal cancer invading the middle hepatic vein and extending into the inferior vena cava. |

Preoperative assessment of the location of the liver tumor in relation to vascular structures is critical. Planning the resection with attention to major venous outflow tributaries with associated drainage areas may identify specific large venous branches that can be preserved for the sake of postoperative liver function (Fig. 30.3). The course of the operation and need for clamping, volume loading, cold perfusion, veno-venous bypass and the need and source of vascular grafts are best identified well before the procedure rather than urgently partway through the operation.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

SURGICAL TECHNIQUEPositioning and Incision

The patient is placed supine. Various incisions can be used, and generally involve some variation of a bilateral subcostal incision with or without a midline extension. (see Figs. 18.7, 19.3 and 21.5)

Alternatively a midline incision with a right extension parallel to the costal margin, or “hockey stick incision” can be used, and either approach can be combined with a midline sternotomy for the sake of exposure of the hepatocaval confluence.

Alternatively a midline incision with a right extension parallel to the costal margin, or “hockey stick incision” can be used, and either approach can be combined with a midline sternotomy for the sake of exposure of the hepatocaval confluence.

Assessment of Resectability

The abdomen is assessed for extrahepatic disease. Portal and aortacaval nodes are assessed. The liver is mobilized by dividing right and left triangular ligaments as well as the gastrohepatic omentum. A replaced left hepatic artery running through the gastrohepatic omentum is identified and preserved if present and required for inflow to the planned liver remnant. In some cases, a large tumor of the right lobe will require an anterior approach without mobilization of the right triangular ligament until after division of the hepatic parenchyma (see Chapter 19). Intraoperative ultrasound can be used to assess tumor size, number and relation to vascular structures. An initial decision regarding resectability and the need for vascular grafts and/or techniques is made at this time, realizing that options may change as the case proceeds.

Strategies to Achieve Vascular Control

Total vascular isolation: Tumors involving the retrohepatic IVC or the hepatic veins as they enter the IVC require various techniques to establish inflow and outflow control in order to minimize blood loss. In total vascular isolation, control of the portal vein and hepatic artery (inflow), and the suprahepatic and infrahepatic IVC (outflow) is established to minimize bleeding from the hepatic artery, portal vein, and hepatic veins. Total vascular isolation may be more damaging than hepatic inflow occlusion alone: Some evidence suggests that hepatic venous back-diffusion may minimize ischemic injury. However, most of the hepatic parenchymal division can usually be performed without total vascular isolation, and clamping of the IVC or hepatic veins can be reserved for the relatively short time period that is required to resect and reconstruct these structures. For total vascular isolation, as much mobilization of the liver off of the vena cava is performed as possible without violating tumor planes prior to hepatic parenchymal transection (see Chapter 19). In some cases, the bulky nature of the tumor inhibits the ability to rotate the liver safely and a primary anterior approach to the IVC can be taken with little or no mobilization of the liver off of the IVC.

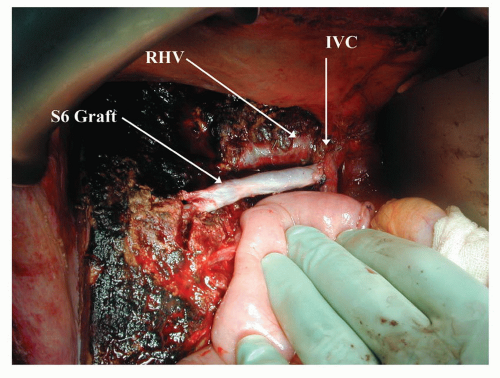

The approach to vena caval resection depends on the extent and location of tumor involvement (Figs. 30.4, 30.5 and 30.6). If the portion of vena cava involved with tumor is below

the hepatic veins, then the parenchyma of the liver can be divided exposing the retrohepatic IVC. The parenchymal transection can be performed with inflow occlusion; however, if possible, the parenchymal division is done while maintaining hepatic perfusion. Central venous pressure is kept at or below 5 cm H2O during parenchymal transection to minimize blood loss. Once the IVC is exposed, portal inflow occlusion, if used, is released, the patient is volume loaded, and clamps are placed above and below the area of tumor involvement. The portion of liver and involved IVC is then removed allowing improved access for reconstruction of the IVC. The placement of clamps on the IVC inferior to the origin of the hepatic veins allows continued perfusion of the liver and minimizes the hepatic ischemic time. Cases where tumor involvement does not allow placement of clamps on the IVC inferior to the origin of the hepatic veins may require some element of cold perfusion of the liver, described below, unless the reconstruction time is expected to be short, cold perfusion techniques can be used. In general the superior anastomosis of the graft is performed first, with clamps subsequently repositioned on the graft below the hepatic veins if necessary to allow release of portal inflow occlusion and reperfusion of the liver to minimize ischemic time (Figs. 30.7

the hepatic veins, then the parenchyma of the liver can be divided exposing the retrohepatic IVC. The parenchymal transection can be performed with inflow occlusion; however, if possible, the parenchymal division is done while maintaining hepatic perfusion. Central venous pressure is kept at or below 5 cm H2O during parenchymal transection to minimize blood loss. Once the IVC is exposed, portal inflow occlusion, if used, is released, the patient is volume loaded, and clamps are placed above and below the area of tumor involvement. The portion of liver and involved IVC is then removed allowing improved access for reconstruction of the IVC. The placement of clamps on the IVC inferior to the origin of the hepatic veins allows continued perfusion of the liver and minimizes the hepatic ischemic time. Cases where tumor involvement does not allow placement of clamps on the IVC inferior to the origin of the hepatic veins may require some element of cold perfusion of the liver, described below, unless the reconstruction time is expected to be short, cold perfusion techniques can be used. In general the superior anastomosis of the graft is performed first, with clamps subsequently repositioned on the graft below the hepatic veins if necessary to allow release of portal inflow occlusion and reperfusion of the liver to minimize ischemic time (Figs. 30.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree