Update on Hiatal Hernia Repair

Raul Rosenthal

Andre Teixeira

Melissa Gianos

Introduction

Definition

The classification of diaphragmatic hernias is distinguished by the position of the gastroesophageal junction. Type I, sliding hiatal hernia, is the most common type. The GE junction has migrated above the diaphragmatic hiatus. With a true paraesophageal hernia, Type II, the GE junction remains in anatomical position without migration. Type II constitutes a large hiatal defect, with herniation of a portion of the stomach through this defect. Type III is a combination of the sliding and paraesophageal hernia. The GE junction migrates into the mediastinum along with the paraesophageal component. The rarest of them all is Type IV, complex paraesophageal hernia, where there is intrathoracic migration of abdominal viscera in addition to the stomach.

Elective repair is based upon hernia type, symptomatology, and the potential complications caused by PEHs. Surgical repair is indicated in patients with reflux-induced damage, in those who are acutely symptomatic, and if risk of necrosis is present. Those patients who are asymptomatic at presentation should be monitored by follow-up radiographic examinations. However, younger asymptomatic patients fit for surgery may be considered surgical candidates due to their longer life expectancy and risk of future complications if left untreated. Contraindications include severe cardiopulmonary disease and risks of surgery outweighing benefits in the elderly population.

Clinical Presentation

The majority of patients are symptomatic upon presentation. Symptom severity is not a predictor of hernia size and further workup is necessary. A minority of patients is asymptomatic upon incidental finding of the hernia.

The most common complaint is chest pain, either substernal or postprandial in nature, often suspected as cardiac in origin. Symptoms include heartburn, belching, regurgitation, dysphagia, nausea, and vomiting. Pulmonary symptoms are commonly present—dyspnea, wheezing, recurrent pneumonia, and aspiration due to chronic cough.

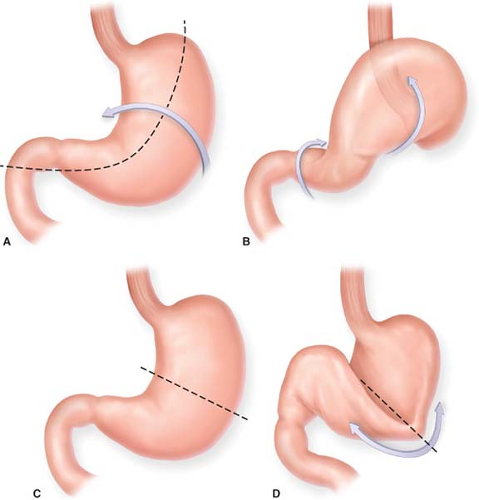

The symptoms experienced by patients with a PEH can be attributed to the volvulization of the stomach. The stomach has two anchoring points—the GE junction and the pylorus. As the stomach ascends into the mediastinum in the hernia sac, it rotates to the upside-down position. Compression of the distal esophagus by the distended stomach can cause dysphagia. The volvulized and distended body of the stomach can limit the lungs’ capacity, causing shortness of breath. Laboratory findings of anemia are due to chronic blood loss from gastric erosions. The organoaxial (long axis of stomach) or mesenteroaxial (perpendicular to long axis) rotation of the stomach is the root cause of PEH complications (Fig. 36.1). The stomach’s volvulization,

distention, and compression precede bleeding, incarceration, and perforation. These life-threatening complications stem from the gastric blood supply being jeopardized.

distention, and compression precede bleeding, incarceration, and perforation. These life-threatening complications stem from the gastric blood supply being jeopardized.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The evaluation of patients with potential PEHs begins with a chest x-ray, and an air-fluid level is seen behind the cardiac shadow if a hernia is present. A contrast esophagram is done to define esophageal anatomy and delineation of esophageal length. Upper endoscopy allows for evaluation of the esophageal lining to detect mucosal erosions as the probable culprit of gastrointestinal blood loss. Manometry is used to assess esophageal dysmotility and localization of the LES. The 24-hour pH test to verify GERD is optional.

Surgical Technique

Positioning

The patient is placed in the supine position, both arms extended at a right angle with the patient positioned in the center of the table. The surgeon and the assistant stand on opposing sides, with the surgeon operating from the right side.