Parastomal Hernia Repair

William S. Cobb

Introduction

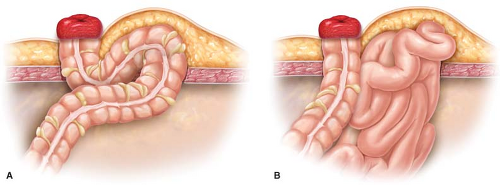

Parastomal hernias are unavoidable following the creation of intestinal conduits to the skin. By definition, all ostomies are hernias because there is a fascial defect to allow passage of the bowel. When additional intraabdominal contents protrude around the fascia at the stoma site, patients may become symptomatic and warrant surgical intervention. The two types of parastomal hernias are the sliding enterostomal defect, which is herniation of the same segment of intestine that forms the ostomy, and the paraenterostomal defect, where a different organ other than the bowel that forms the stoma is involved (Fig. 31.1).

The incidence of true parastomal hernias varies greatly and depends on how aggressively the surgeon investigates its presence. The incidence of parastomal hernia is quoted as 30% to 35% on physical examination and increases to a rate greater than 60% when computed tomography of the abdomen is included. Factors that increase the incidence of parastomal hernia formation include placement of the ostomy lateral to the rectus sheath, ostomy aperture greater than 2.5 cm, and advancement in age.

The majority of patients with parastomal defects are asymptomatic at presentation. The hernia presents itself as fullness or pain at the ostomy site. Frequently, the defects are found incidentally on computed tomography imaging of the abdomen for other pathology. Most asymptomatic parastomal hernias can be treated with “watchful waiting.” Patients should be given the warning signs of a symptomatic hernia and especially cautioned regarding the possibility of incarceration or strangulation of the hernia.

The most common indication for repair of parastomal hernias is pain at the ostomy site. Obstructive symptoms, particularly nausea and vomiting, diminished ostomy output, and admissions for partial small obstruction, should be elucidated from the patient. Frequently, patients seek surgical intervention as a result of problems with the ostomy appliance consisting of either poor fit or leakage of enteric contents at the site.

Contraindications for repair would include patients that are poor candidates for general anesthesia either from a cardiac or pulmonary standpoint. The inability to tolerate general anesthesia will typically preclude a laparoscopic repair. Any decision regarding repair of parastomal hernias should consist of an appraisal of the risks versus benefits unique to each patient.

The best way to manage a parastomal hernia is to convert it to an incisional hernia by reversing the ostomy. Many times, patients have not been properly considered for ostomy reversal. This possibility needs to be addressed prior to embarking on a mesh-based repair of any parastomal defect. It may be necessary to locate previous operative or outpatient notes to identify this possibility.

Many patients presenting for repair of parastomal hernias have additional comorbidities that may complicate their perioperative course. Achieving a durable repair of parastomal defects is difficult enough to warrant medically maximizing the patient as best as possible.

Patients who use tobacco should be made to stop. Tobacco use has been demonstrated in several studies to increase the risk of wound and mesh infections. A urine nicotine level on the preoperative visit or the day of surgery may be drawn to exclude patients that continue to smoke.

Morbid obesity frequently accompanies parastomal hernias. Frank discussion with patients regarding weight loss and potentially bariatric surgery should be had. This conversation takes on added importance in situations of multiply recurrent parastomal defects.

The preoperative conversation with the patient should include expected postoperative outcomes related to the hernia repair. The possibility of mesh infection and damage to the ostomy are real and should be discussed. The long-term recurrence rate is higher than for ventral hernia repairs and approaches 30% for all comers according to the literature.

Imaging of the abdomen should be considered in patients with parastomal hernia, particularly if it is a recurrent defect with previously placed intraabdominal mesh. With laterally displaced defects, the landing zone for mesh may be compromised by the iliac crest. In this situation, bone anchors may be required to fixate the mesh laterally.

Preoperative mechanical bowel preparation is not necessary. Many times bowel cleansing may complicate the repair as a result of drainage of intestinal contents from the ostomy during the repair.

The surgical repair of parastomal hernias is divided into three main approaches: (1) Primary, suture-based repair of the defect, (2) relocation of the ostomy, and 3) mesh-based repair of the defect. A straightforward, suture repair of the parastomal defect does not provide a long-term solution, but may be the preferred approach in a symptomatic patient who is a poor surgical candidate. Synthetic mesh or a biologic graft may be used as an onlay to reinforce a suture-based repair of a parastomal defect. Relocation of the ostomy is a viable option, particularly for large defects, but the concern is for creating two hernia prone sites on the abdominal wall. The technique portion will focus on the mesh-based repairs of parastomal hernias.

Preparation and Positioning

Preparation of the parastomal hernia patient requires management of the ostomy prior to cleansing the abdominal wall of the patient. The ostomy site is closed with a purse-string suture of 2-0 silk. For ileal conduits, a catheter is used to cannulate the ostomy. The abdomen is prepped with povidone-iodine or silver chlorhexidine scrub. A sterile clear adhesive dressing (Tegaderm) is placed over the ostomy site. The entire abdomen is then covered with an adhesive iodine-impregnated drape (Ioban).

Systemic antibiotics are given preoperatively just as with a mesh-based incisional hernia repair and consist of a first-generation cephalosporin given 1 hour prior to incision. The dose is adjusted for weight and re-dosed at 4 hours. Prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis should be instituted with sequential compression hose and subcutaneous heparin for high-risk patients.

Open Repair

Mesh can be placed either in the retro-rectus or intraabdominal position in the repair of parastomal defects. A midline approach is preferred given that most cases have a midline incisional defect as well. The patient is positioned with the arms out and padded. A urinary catheter is placed for decompression. The previous midline cicatrix is excised. The abdominal cavity is entered and adhesiolysis is undertaken. The contents of the hernia sac are reduced and the fascial edges are delineated. Excision of the hernia sac is not necessary.

The posterior sheath of the rectus is identified and carefully dissected free of the rectus muscle. The retro-rectus space is developed on both sides out laterally to the insertion of the oblique muscles. On the side of the ostomy, the posterior sheath is dissected off the edges of the parastomal defect.

If the parastomal defect is in the midbody of the rectus muscle, there should be enough overlap for placement of mesh. If the ostomy defect is outside of the rectus sheath or adjacent to the lateral edge of the rectus sheath, the posterior sheath can be carefully incised at the lateral edge of the rectus to enter the preperitoneal space and allow for lateral placement of mesh (Fig. 31.2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree