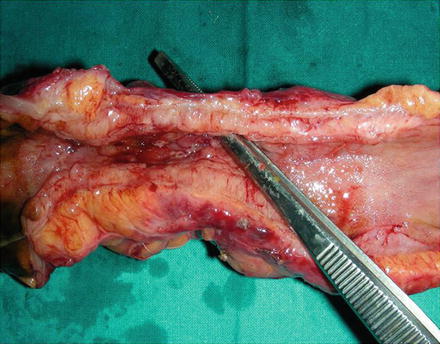

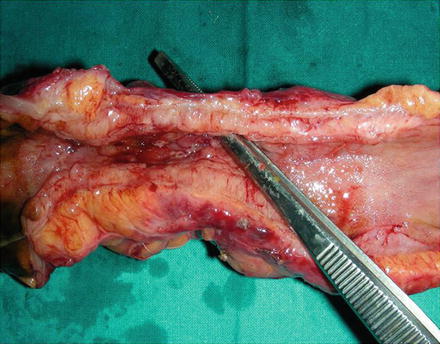

Fig. 2.1

Surgical section of small bowel from a patient with Crohn’s disease. The wall (arrows) is significantly thickened especially at the level of muscularis propria. By courtesy of Prof. Chiara Montesani and Anna Maria Pronio, University of Rome “Sapienza”, Italy

Therefore, recent interest has focused on implementing radiation-free, cross-sectional techniques, primarily ultrasound (US) and magnetic resonance (MRI). US and MRI, like CTE, and unlike traditional barium studies and endoscopy, assess the entire intestinal wall, can evaluate mucosal as well as transmural alterations, and allow a complete and accurate staging of the bowel, abdomen and perineum with the unique advantage to assess mural and extramural disease.

In this chapter we will target the applications and limitations of bowel US in IBD, focusing on the usefulness of bowel US in the early detection and follow-up of Crohn’s disease, affecting mostly the small bowel. Endoscopy continues to be the reference standard to evaluate the upper and lower GI tract.

Bowel Ultrasound in Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease

Due to noninvasiveness, low cost, radiation-free and widespread availability, transabdominal ultrasound (TUS) is a very useful modality for IBD imaging [14–16], while disadvantages include operator dependency and difficulty to thoroughly visualize the entire GI tract, since the lumen is virtual and it may contain gas, a condition that hinders sonographic reflection [16, 17]. Over the past few years, technological development, including high frequency transducers (typically 7–12 MHz), harmonic imaging combined with the use of oral (small intestine contrast ultrasonography, SICUS) [18–20], and intravenous contrast agents (CE-US), have improved performance of ultrasound in the assessment of the gastrointestinal tract [21, 22].

The detection of bowel diseases relies on the assessment of intestinal wall and lumen, on the detection of enlarged mesenteric nodes, and/or of fluid in the peritoneal cavity.

At ultrasound the normal bowel wall is characterized by the presence of five concentric layers alternately hyperechoic and hypoechoic (Fig. 2.2). Normal stratification of the bowel wall is defined by the presence of the five layers, while loss of stratification is defined by the lack of one or more layers [16]. The normal bowel wall thickness has been reported to be <3–4 mm and <1.5–3 mm in the terminal ileum, and ≤ 5 mm and <2 mm in the colon, in adults and in children, respectively. The assessment of bowel vascularisation by color Doppler provides additional information, particularly on disease activity (Fig. 2.3). The vascularity of bowel wall can be assessed according to the intensity of color signals or by the analysis of Doppler curves from vessels within the bowel wall [23].

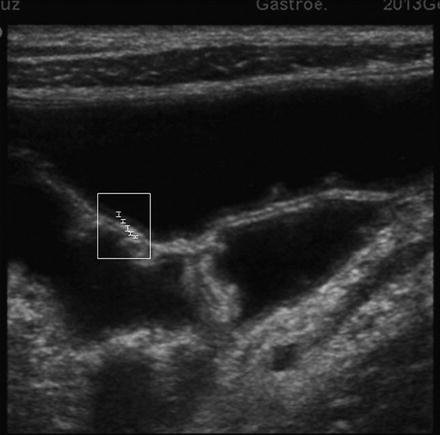

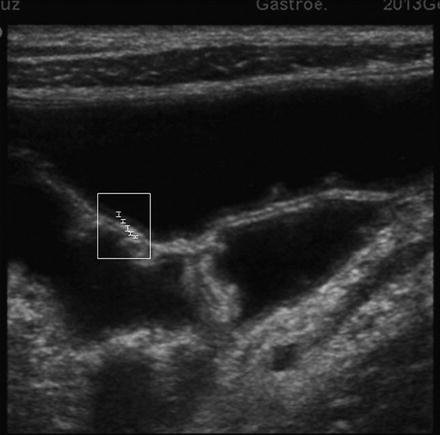

Fig. 2.2

Small Intestinal Contrast Ultrasonography (SICUS) image of two adjacent jejunal loops after oral administration of the anechoic contrast solution. The five layers of the wall are recognizable (white lines) starting luminally: (1) a thin echogenic layer, (2) hypoechoic layer, (3) hyperechoic layer, (4) hypoechoic layer, and (5) a hyperechoic layer

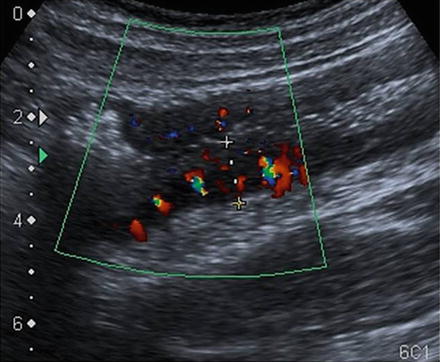

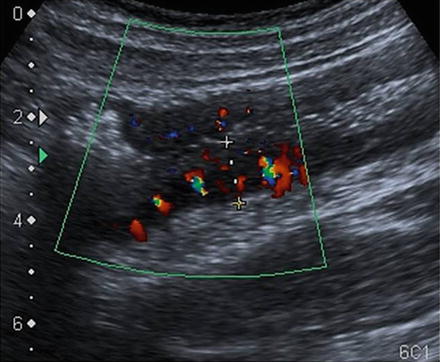

Fig. 2.3

Color Doppler examination of the descending colon in active CD. Mural thickening, loss of stratification of the bowel wall, and increased vascularity on color Doppler denoting inflammatory hyperemia. By courtesy of Fortunata Civitelli, MD Department of Pediatrics, Pediatric Gastroenterology and Liver Unit, Sapienza University of Rome

Crohn’s Disease

Bowel TUS has become the first-line imaging procedure in the diagnostic work-up of patients with suspected Crohn’s disease [1, 24] and in the follow-up of patients with known CD. In CD the intestinal wall is often macroscopically greatly thickened (Fig. 2.1). In addition, the transmural inflammation progresses deeply into the serosa and outside, potentially producing fissures and fistulae (Fig. 2.4 ), which may reach adjacent loops, organs, and skin or end blindly in the mesentery or resulting, at times, in intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal abscesses. The mesentery surrounding diseased loops is often thickened and fatty (Fig. 2.1 and Fig. 2.2) and may contain enlarged lymph nodes (Fig. 2.5). The diagnosis of CD with ultrasound relies on the assessment of those pathological features that may be essentially differentiated in mural and extramural features [16]. At ultrasound the pathological mural alterations appear as: (1) increased thickness of intestinal wall (Fig. 2.6), (2) variation of transmural echopattern (Fig. 2.7a), (3) interruption or loss of echo-stratification (Fig. 2.7b), (4) presence of variable enlargement of the different five layers, (5) increased Color-Doppler signal (Fig. 2.3), and (6) loss or reduction of peristalsis in the small bowel and of haustra coli in the colon. In early CD the wall stratification is usually preserved, the submucosa is thickened and appears as a hyperechoic band (Fig. 2.6), while in severe disease the stratification may disappear (Fig. 2.7a, b). In longstanding disease fibrosis results in thickened bowel wall, which is hypoechoic with loss of normal stratification; moreover fibrofatty proliferation of the mesentery tends to isolate pathologically stiff loops. At ultrasound the pathological extra-mural changes are assessed by the presence of: (1) fatty hypertrophy of the surrounding mesentery (Fig. 2.8), (2) enlarged lymph nodes (Fig. 2.5), (3) abscesses (Fig. 2.9), (4) fistulas (Fig. 2.10).

Fig. 2.4

Surgical section of small bowel from a patient with Crohn’s disease. The lumen is narrowed and the forceps show a fistula arising from the lumen through the thickened wall. By courtesy of Prof. Chiara Montesani and Anna Maria Pronio, University of Rome “Sapienza”, Italy

Fig. 2.5

SICUS. Thickened hyperechoic mesentery with enlarged mesenteric node (A). The intestinal lumen is distending by anechoic contrast

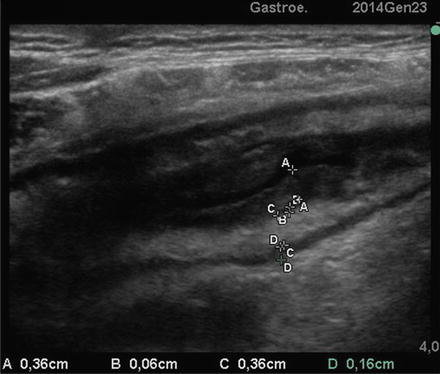

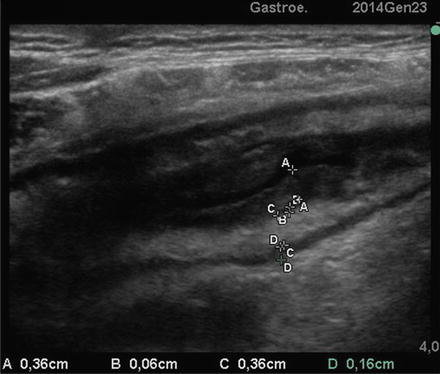

Fig. 2.6

CD of small bowel at SICUS: thickened small bowel wall characterized by a stratified echopattern with thickening of mucosa (A-A) and submucosa (C-C)

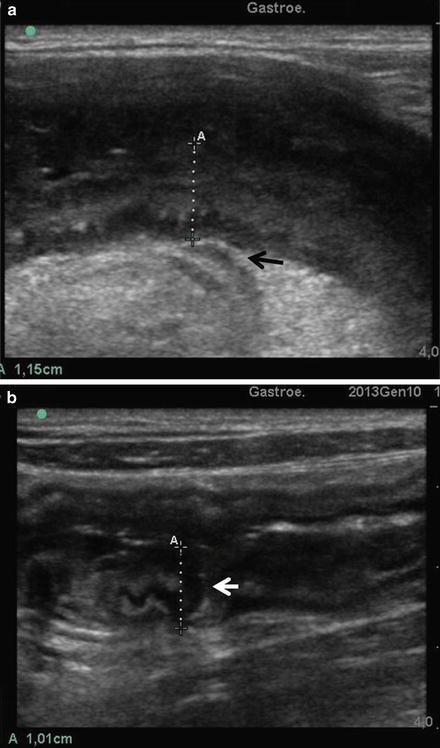

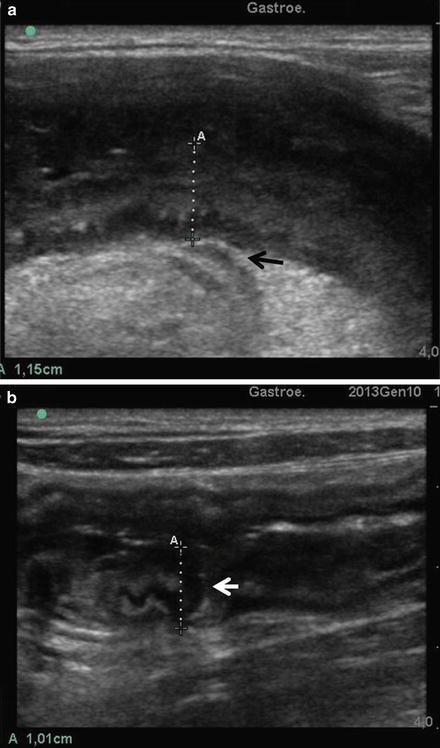

Fig. 2.7

CD of small bowel at SICUS. (a) The wall is thickened with loss of multilayered stratification with a hypoechoic peri-intestinal lesion (arrow) arising from the thickened intestinal wall through a wrapping mesentery. (b) The wall is thickened (A) with loss of multilayered stratification with a hypoechoic lesion (arrow) penetrating the thickened intestinal wall

Fig. 2.8

SICUS appearance of mesenteric fat hypertrophy (arrowhead), and of entero-mesenteric fistula (arrows)

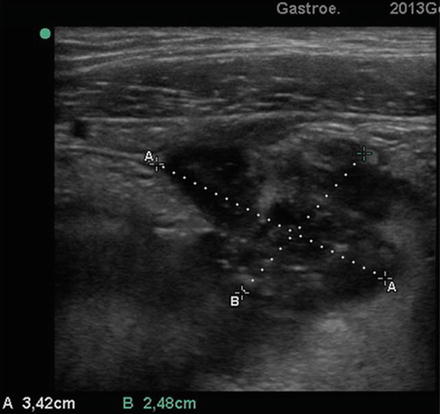

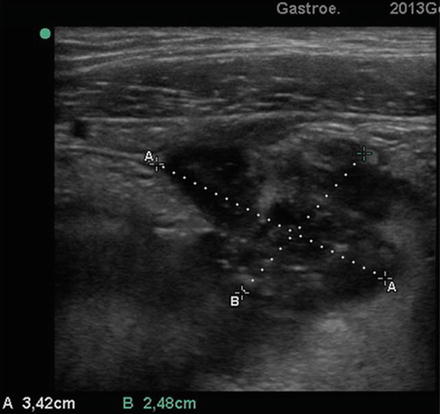

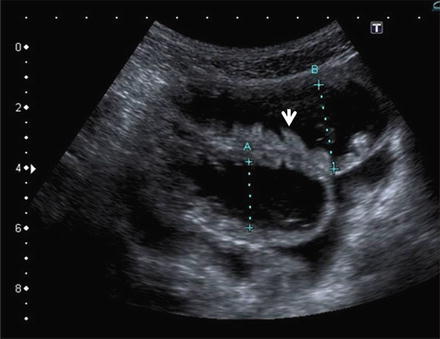

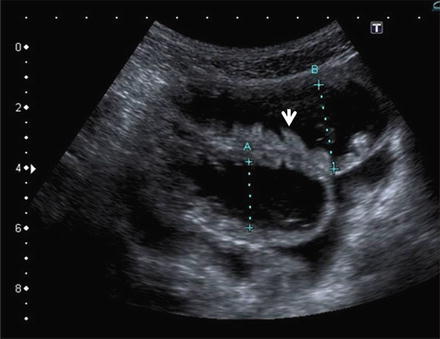

Fig. 2.9

Transverse US section (3.5 MHz probe) at level of the lower abdominal right quadrant. A round-shaped hypoechoic image of 3.4 cm (see calipers) is shown

Fig. 2.10

Entero-enteric fistula appearance at SICUS as hypoechoic ducts between the intestinal loops (arrows). Note the anechoic contrast distending the lumen and the mesenteric fat hypertrophy

Bowel Ultrasound in the Early Assessment of Patients with the Suspicion of Crohn’s Disease

Abnormal bowel wall thickness (BWT) is the most important TUS sign of CD and in unselected groups of patients, based on BWT values, sensitivities of 75–94 % with specificities of 67–100 % have been reported [15, 25, 26]. The wide variability of sensitivity and specificity values across studies reflects differences in the study design, size, and characteristics of the study samples and in the different reference standard value as threshold for a positive diagnosis. These methodological issues were evaluated in a meta-analysis [27] that, starting from 44 full-text studies, recognized only 7 prospective and appropriately designed studies (5 case control and 2 cohort studies). The results of this analysis showed that when more than 3 mm cut-off level was applied for abnormality in wall thickness, the sensitivity and specificity of TUS in the diagnosis of CD were 88 % and 93 %, while when a cut-off level of more than 4 mm was used, sensitivity was 75 % and specificity 97 %. The role of US to assess CD has been most extensively investigated for small bowel CD and the highest reported level of diagnostic sensitivity of TUS was achieved in investigations performed in populations mainly affected by known CD located in the terminal ileum [24]. This study, however, lacks a control group and was carried out by qualified investigators with specific expertise in tertiary referral centers. Several studies evaluated the accuracy of TUS in localizing Crohn’s disease lesions and most of them agreed in reporting the highest sensitivity (approximately 90 %) of TUS in detecting CD located in the terminal ileum and the lowest accuracy for those located in the upper small bowel and in the rectum [17, 28]. Few studies have evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of TUS as a screening technique for yet undiagnosed small bowel pathology [17], and most report unsatisfactory sensitivity (74–85 %). The main limit of bowel TUS is its inability to visualize the entire gut that has a virtual lumen and may contain gas making the intestinal wall barely visible. However, the difficulty in visualizing bowel wall is overcome by distending the intestinal lumen with anechoic fluid. After the ingestion of small amounts (250–375 mL) of polyethylene glycol 3,350–4,000 (macrogol) solution [17, 18], the entire small bowel from the duodenal-jejunal angle to ileocecal valve can be visualized with the Small Intestine Contrast US (SICUS). SICUS undertaken in healthy controls in vivo and independent of the volume of oral contrast used, allowed objective normative values of wall thickness (≤ 3 mm) and lumen diameter (≤25 mm) to be defined (Table 2.1, Video 2.1) [19]. These normative values provide useful measurements to discriminate normal from abnormal findings. Based on these normal cut-off values, it has been shown that SICUS is comparable to radiology and superior to standard TUS in detecting intestinal lesions both in patients with undiagnosed small bowel diseases and in those with known CD (Tables 2.2 and 2.3) [17, 20]. Sensitivity of TUS and SICUS were 57 % and 100 % and 87.3 % and 98 %, in the undiagnosed and in known CD patients, respectively. In addition, it has been shown that SICUS is more accurate than TUS in detecting both proximal and distal small bowel CD lesions compared to radiology [17] and surgery [29] (Table 2.4, Video 2.2). These results have subsequently been confirmed by other authors in several studies [30–32].

Table 2.1

SICUS: Normal values of wall thickness and lumen diameter of small bowel in healthy controls assessed in two consecutive evaluations

Location | Wall thickness (mm) | Lumen diameter (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

1st | 2nd | 1st | 2nd | |

Jejunum | 1.7 ± 0.4 1–2 | 1.2 ± 0.4 1–2 | 18.4 ± 2.3 15–21 | 16.8 ± 2.2 15–21 |

Ileum | 1.9 ± 0.3 1.3–2 | 1.2 ± 0.4 1–2 | 18.4 ± 1.8 16–20 | 17.8 ± 2.8 13.7–20 |

Terminal ileum | 1.9 ± 0.3 1.3–2 | 1.7 ± 0.6 1–2.3 | 17.2 ± 2.2 14–20 | 15.7 ± 2.8 11.3–19 |

Table 2.2

Sensitivity and specificity of TUS and SICUS in detecting small bowel lesions in undiagnosed patients

Patients | TUS | SICUS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

n (%) | TP | FN | TP | FN | |

IBS | 36 (39.6) | – | 0 | – | 0 |

Crohn’s disease | 16 (17.6) | 11 | 5 | 16 | 0 |

Ulcerative colitis | 7 (7.7) | – | 0 | – | 0 |

Malignant tumors | 6 (6.6) | 3 | 3 | 6 | 0 |

Celiac disease | 5 (5.5) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

Undefined colitis | 4 (4 %) | – | 0 | – | 0 |

Polyps | 4 (4 %) | 0 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

Others | 13 (14.3 %) | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

Total | 91 (100 %) | 20 | 15 | 33 | 2 |

Table 2.3

Sensitivity and specificity of TUS and SICUS in detecting small bowel lesions in patients with known CD

Patients | TUS | SICUS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Lesion | n (%) | TP | FN | TP | FN |

Terminal ileum | 18 (32.7) | 14 | 4 | 17 | 1 |

Ileum-jejunum | 23 (41.8) | 20 | 3 | 23 | 0 |

Ileo-colonic | 14 (25.5) | 14 | 0 | 14 | 0 |

Total | 55 (100) | 48 | 7 | 54 | 1 |

Table 2.4

Agreement between TUS and SICUS and surgery and SBFT in the detection of the small bowel CD lesion site

Patients | TUS | SICUS | |

|---|---|---|---|

N | k | k | |

Surgery | |||

Proximal lesions (≥1) | 8 | 0.54 | 0.93 |

Distal lesions (≥1) | 39 | 0.68 | 0.93 |

SBFT | |||

Proximal lesions (≥1) | 12 | 0.31 | 0.83 |

Distal lesions (≥1) | 45 | 0.61 | 0.93 |

Notably SICUS enables initial assessment of wall alteration limited to the mucosa and submucosa in CD (Fig. 2.11). The latter is associated with slight thickening of the intestinal wall, which may be missed in absence of the lumen distension by oral contrast (Video 2.3). Furthermore, SICUS allows identification and assessment of the characteristic distribution of intestinal folds (Fig. 2.12) and recognition of endoluminal structures such as polyps from the intestinal wall (Fig. 2.13, Video 2.4).

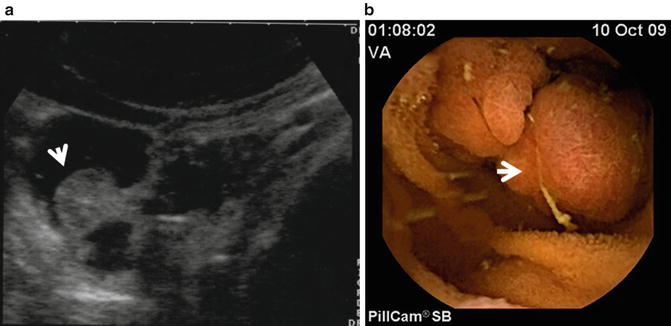

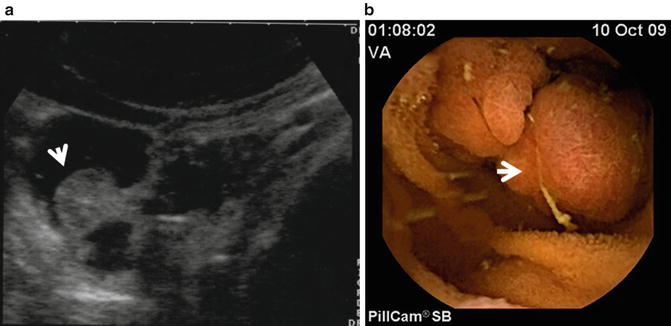

Fig. 2.11

SICUS: the thickness of intestinal wall appears slightly increased with a multilayered structure and mucosa enlargement (A-A)

Fig. 2.12

SICUS: The longitudinal scan demonstrates anechoic contrast filled lumen; intestinal folds are seen as tiny intraluminal echogenic indentations of the intestinal wall (arrow)

Fig. 2.13

Polyp of the small bowel. Panel A: SICUS: a fixed round echogenic structure (arrow) is visible within the contrast-filled ileal lumen. Panel B: Wireless capsule endoscopy: a corresponding endoscopic image. By Courtesy of Erminia Romeo, MD and Luigi Dall’Oglio, MD Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù Rome, Italy

It has been recently shown that SICUS is a safe, accurate, radiation-free alternative for the assessment of small bowel disease also in pediatric patient population [28]. The reported ability of SICUS to accurately identify the presence of small bowel disease compared to small bowel follow-through (SBFT) and ileocolonoscopy in a pediatric cohort of patients is even higher than in adults with a sensitivity and specificity of 96 % and 100 %, respectively (Table 2.5). In addition, as in adults, this study confirmed that SICUS is as accurate as SBFT in detecting both proximal and distal small bowel lesions, whereas agreement with SBFT was markedly lower for TUS without oral contrast, mainly for the proximal sites lesions (Table 2.5). Although feasibility and reliability of this technique in pediatric clinical practice ought to be confirmed in further studies, the diagnostic accuracy of SICUS, with a considerable negative predictive value and such high level of agreement with radiology, suggests that a normal SICUS at the initial diagnostic workup in a child with suspected CD could avoid radiation exposure and invasive and/or more expensive investigations.

Table 2.5

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and statistical agreement of SICUS and TUS with SBFT in detecting presence and site of small bowel CD lesions in pediatric patients

Modality | Site | SE % (95 % CI) | SP % (95 % CI) | PPV % (95 % CI) | NPV % (95 % CI) | k | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

TUS | Proximal | 50 (23–76) | 100 (87–100) | 100 (60–100) | 79 (62–91) | 0.40 | ns |

Distal | 83 (64–94) | 100 (68–100) | 100 (83–100) | 69 (45–91) | 0.68 | 0.05 | |

SICUS | Proximal | 93 (66–100) | 100 (87–100) | 100 (75–100) | 96 (81–100) | 0.93 | <0.05 |

Distal | 97 (81–100) | 100 (68–100) | 100 (85–100) | 92 (60–100) | 0.94 | <0.001 |

It should be pointed out that compared to standard TUS, SICUS is a time-consuming technique, the duration of the examination being on average 45 min. Although SICUS may appear to be a more expensive technique than traditional TUS, the lack of radiation actually makes it a cost-effective alternative to the less available and more expensive MRI. When considering colonic CD, US is more accurate in the assessment of intestinal wall pathology located in the sigmoid/descending colon, followed by the cecum/ascending, and transverse colon, while accuracy for rectal disease is poor [33]. A systematic review of 6 studies investigating US for assessment of ileo-colonic CD found sensitivities ranging from 63 to 100 % and specificities from 77 to 100 % [27]. The accuracy of standard ultrasound compared to endoscopy in the assessment of presence and severity of CD located in the colon improves markedly with hydrocolonic sonography [34], but these findings have not been reproduced.

The effectiveness of intravenous contrast agents in the detection of Crohn’s disease remains, despite some positive findings, largely uninvestigated [21].

Assessment of Extension of Lesions of Crohn’s Disease

To date few studies have assessed the accuracy of ultrasound to assess extension of CD intestinal involvement and reports have been equivocal regarding the correlation of TUS with radiology and intraoperative findings [33, 35–37]. Two studies [33, 35] performed in the same group of patients reported a significant correlation (r = 0.51) between TUS and small bowel enema in the assessment of CD lesion extension. However, this finding was not confirmed by a study that, while not contradicting such correlation, showed that when an appropriate test of comparative analysis is employed, (i.e., ANOVA), the accuracy of TUS in the assessment of extension of small bowel lesions is lower than that observed at SICUS and confirmed by SBFT or surgery [17, 29].

The use of oral contrast improves ultrasound accuracy in assessing extension of small bowel CD lesions in both adults and children independent of the site of lesions (Figs. 2.14 and 2.15).

Fig. 2.14

One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test for comparative evaluation of the extent of small bowel lesions at transabdominal ultrasonography (TUS), SICUS, and small bowel follow-through (SBFT)

Fig. 2.15

Extension of small bowel CD lesions at TUS, SICUS and surgery. The difference between paired measurements of CD lesion length at SICUS and at TUS and surgery against their mean and statistical difference is also reported

These findings are of clinical relevance in patients with suspected CD, as well as in those with a previously established diagnosis, to help address follow-up and appropriate management of a progressive disease.

Assessment of Crohn’s Disease Activity

Assessment of inflammatory activity is a central component of the management of Crohn’s disease patients. Measurement of disease activity has traditionally involved a combination of clinical, biochemical (ESR, CRP, α1-antitrypsin, fecal calprotectin), imaging, and endoscopic methods; although no ideal reference standard currently exists [38]. Clinical scoring systems such as the CDAI have been shown to have low correlation with mucosal inflammation, poor inter-observer reproducibility and, more relevantly, may not detect asymptomatic inflammation [39]. Laboratory parameters are not specific and endoscopy, including double balloon enteroscopy, is invasive and limited to mucosal assessment. Computed tomography (CT) involves the use of ionizing radiation whereas magnetic resonance (MR) imaging is expensive and time consuming. Several studies evaluated the relationship between CD activity assessed as CDAI and/or with biochemical parameters, and TUS features of the bowel wall with equivocal results [40–42]. Previous studies have shown significant but weak correlation between the degree of bowel wall thickening and its extent and clinical (CDAI) and biochemical parameters (ESR, CRP) [40]. As such, an ultrasound index of intestinal inflammatory activity has been developed based on the wall thickness and stratification of the diseased gut demonstrating a strong correlation with the endoscopic and radiological score but a weak correlation with clinical (CDAI) and biological indices of inflammation [41].

The introduction of second-generation ultrasound contrast agents in combination with low mechanical index harmonic ultrasound allows accurate imaging and analysis of bowel wall microvascularity that takes part in the pathogenesis of CD inflammation [43]. Several studies have examined both qualitative and quantitative measures of bowel wall enhancement obtained from CEUS as a means of assessing inflammatory activity in Crohn’s disease with inconsistent results [44–49]. Some studies have demonstrated a significant relationship between measurements obtained from CEUS and clinical or endoscopic indices of disease activity [44, 45] while others have failed to confirm similar results [46, 47], suggesting that mural microvascularity may be variably increased in active disease. Experimental data have previously shown that regional blood flow is, in fact, reduced in Crohn’s disease and associated to microvascular ischaemia [49].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree