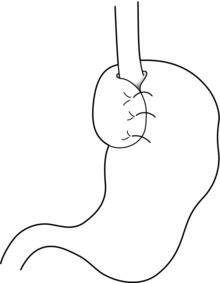

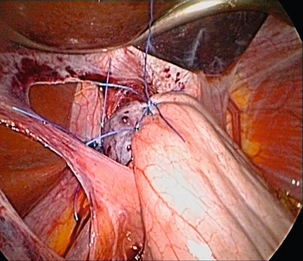

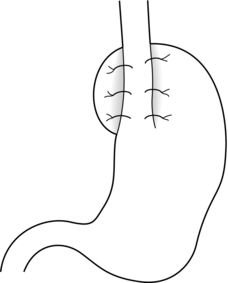

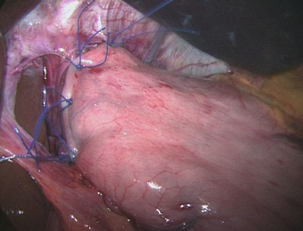

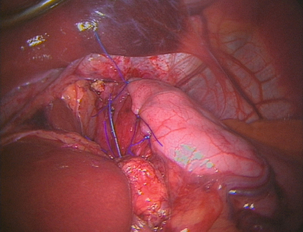

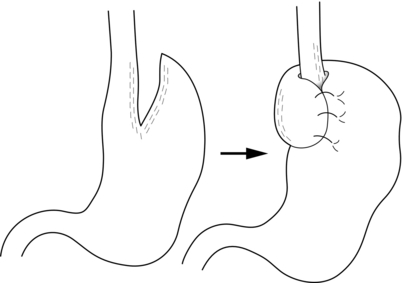

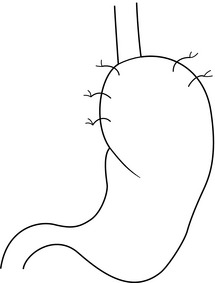

13 Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is common, affecting between 10% and 40% of the population of most Western countries.1,2 It is difficult to establish if the incidence of GORD is increasing but it is certainly the case that more and more patients are being treated for reflux. This is reflected in a dramatic rise in the overall cost of medical therapy for GORD in many countries over recent decades. In addition, the incidence of distal oesophageal adenocarcinoma is increasing,3 which provides circumstantial evidence that complications of gastro-oesophageal reflux, such as the development of Barrett’s oesophagus, are also increasing. GORD is caused by excessive reflux of gastric contents, which contain acid and sometimes bile and pancreatic secretions, into the oesophageal lumen. Pathological reflux leads to heartburn, upper abdominal pain and the regurgitation of gastric contents into the oropharynx. A multifactorial aetiology is most likely. Hiatus herniation is associated with reflux in approximately half of the patients who undergo surgical treatment.4,5 This results in widening of the angle of His, effacement of the lower oesophageal sphincter and loss of the assistance of positive intra-abdominal pressure acting on the lower oesophagus. Reduced lower oesophageal sphincter pressure is also often found. In patients with normal resting lower oesophageal sphincter pressure, reflux may result from an excessive number of transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxation events.6 Other factors that might contribute to reflux are abnormal oesophageal peristalsis (which causes poor clearance of refluxed fluid) and delayed gastric emptying. The treatment of reflux is incremental, commencing with medical measures, surgery being reserved for patients with more severe disease who either fail to respond adequately to medical treatment or who do not wish to take lifelong medication. In basic terms, medical therapy treats the effects of reflux, as the underlying reflux problem is not corrected, and treatment is usually continued indefinitely.7 In contrast, surgery aims to be curative, preventing reflux by reconstructing an antireflux valve at the gastro-oesophageal junction.6,8 In the past, surgery was reserved for patients with complicated reflux disease or those with very severe symptoms. However, since the introduction of laparoscopic surgical approaches some surgeons advocate utilising surgery at earlier stages in the course of reflux disease. Endoscopic (transoral) antireflux procedures have also been developed, although the outcomes following these treatments have been disappointing. When first used in the 1970s, histamine type 2 (H2)-receptor antagonists, which reduce the production of gastric acid, revolutionised the medical approach to duodenal ulcer disease. However, they were less effective for reflux disease and although they sometimes relieve mild to moderate reflux symptoms, few patients achieve complete relief of symptoms.9 With the current widespread availability of proton-pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists are now rarely used as first-line medical therapy. Proton-pump inhibitors (omeprazole, lanzoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole and esomeprazole) were introduced into clinical practice in the late 1980s.7 Proton-pump inhibitors are much more effective at symptom relief and achieve better healing of oesophagitis than H2-receptor antagonists. However, in patients with severe oesophagitis (Savary Miller grade 2/3) there is a high treatment failure rate,10 and many patients who initially achieve good symptom control develop ‘breakthrough’ symptoms at a later date, requiring an increased dose of medication to maintain symptom control. Failure may be due to inadequate acid suppression, although in some cases bile or duodenal refluxate may play a role. In patients who respond well to proton-pump inhibitors, symptoms usually recur rapidly (sometimes in less than 24 hours) following cessation of medication, and for this reason lifelong medical treatment is likely to be required.7 The long-term use of proton-pump inhibitors appears generally safe. One study has shown, however, that long-term use can be associated with the development of atrophic gastritis with intestinal metaplasia in patients with concurrent Helicobacter pylori infection.11 Long-term use can also be associated with parietal cell hyperplasia.12 This latter phenomenon may be the reason why symptoms recur rapidly in some patients on cessation of therapy, and may be another reason why some patients require escalating dosages of proton-pump inhibitors to control their symptoms. Cisapride is the only prokinetic agent that has been shown to be better than placebo for the treatment of reflux.13 It acts by improving acid clearance from the distal oesophagus by accelerating gastric emptying. Its therapeutic benefit is similar to that of the H2-receptor antagonists. Hence, its clinical role has been limited since proton-pump inhibitors became widely available. An incidence of cardiac arrhythmias in the 1990s led to its withdrawal in most parts of the world. As a general rule, all patients who undergo antireflux surgery should have objective evidence of reflux. This may be the demonstration of erosive oesophagitis on endoscopy or an abnormal amount of acid reflux demonstrated by 24-hour pH monitoring. Neither of these tests is sufficiently reliable to base all preoperative decisions on their outcome,14 as a number of patients with troublesome reflux will have either a normal 24-hour pH study or no evidence of oesophagitis at endoscopy (and, very occasionally, both). For this reason the tests have to be interpreted in the light of the patient’s clinical presentation, and a final recommendation for surgery must be based on all available clinical and objective information.14 More recently, impedance monitoring (in combination with pH monitoring) has been used to measure ‘volume’ reflux, although the additional information obtained from this investigation appears unlikely to influence surgical decision-making.15 Reflux with stricture formation: In the past, surgery was the only effective treatment for strictures, and when the stricture was densely fibrotic this even meant resection of the oesophagus. Fortunately, it is now unusual to see patients with such advanced strictures since proton-pump inhibitors became available, so that the role of surgery seems to have lessened.16 Strictures in young and fit patients are usually best treated by antireflux surgery and dilatation. However, many patients who develop strictures are elderly or infirm and the use of proton-pump inhibitors with dilatation is usually effective in this group. Reflux with respiratory complications: When gastro-oesophageal regurgitation spills over into the respiratory tree, this can cause chronic respiratory illness, such as recurrent pneumonia, asthma or bronchiectasis. This is a firm indication for antireflux surgery, as the predominant action of proton-pump inhibitors is to block acid secretion and the volume of reflux is not greatly altered. Reflux with throat symptoms: Halitosis, chronic cough, chronic laryngitis, chronic pharyngitis, chronic sinusitis and loss of enamel on teeth are sometimes attributed to gastro-oesophageal reflux. Whilst there is little doubt that on occasions such problems do arise in refluxing patients, these problems in isolation are not reliable indications for surgery. Whether or not these symptoms will be relieved following surgery is unpredictable. If symptoms are associated with typical reflux symptoms such as heartburn and/or regurgitation, then response rates of approximately 80% are reported, whereas throat symptoms in the absence of typical reflux symptoms respond poorly to surgery, with success rates of less than 50% reported.17 Columnar-lined (Barrett’s) oesophagus: Patients with Barrett’s oesophagus who have reflux symptoms should be selected for surgery on the basis of their symptoms and their response to medications, not simply because they have a columnar-lined oesophagus.18 There is some experimental evidence to suggest that continuing reflux may be deleterious in regard to malignant change in oesophageal mucosa,19 and one prospective randomised trial has suggested that antireflux surgery gives superior results to drug therapy in this patient group.19 However, proton-pump inhibitors were only introduced into the medical arm of that trial in its later years. There is also evidence that abolition of symptoms with proton-pump inhibition does not equate to ‘normalising’ the pH profile in a patient’s oesophagus.20 Since antireflux surgery does abolish acid reflux, this may become a further reason to recommend surgery in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus. However, there is only limited evidence that either surgical or medical treatment of reflux in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus consistently leads to regression of the columnar lining.21 A report by Gurski et al.22 suggested that although fundoplication is not followed by a reduction in the length of Barrett’s oesophagus, it can be followed by ‘histological’ regression. In 68% of patients in this study with low-grade dysplasia, there was regression to non-dysplastic Barrett’s mucosa. Equally, studies have shown that combining medical or surgical therapy with argon-beam plasma coagulation, photodynamic therapy or radiofrequency ablation of the columnar lining achieves complete or near complete reversion to squamous mucosa.23–25 There is no evidence to support that antireflux surgery reduces the risk of dysplastic or neoplastic progression of Barrett’s oesophagus. Medical therapy, in the form of proton-pump inhibitors, is so effective that only a minority of patients do not get substantial or complete relief of their symptoms using these agents. Despite this, patients continue to present for antireflux surgery in large numbers for reasons already discussed. An additional factor that has emerged is the rising incidence of adenocarcinoma of the cardia associated with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.3 Whether antireflux surgery is more effective than long-term proton-pump inhibition at preventing the development of columnar-lined oesophagus and subsequently carcinoma of the lower oesophagus is controversial. If duodenal fluid has a role in the pathogenesis of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus, then antireflux surgery would be preferable to acid suppression alone in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus, and of course it may also prevent the development of Barrett’s oesophagus in the first place. However, this hypothesis is not adequately tested and at present there is insufficient evidence to support a position that antireflux surgery should be performed to prevent subsequent malignant transformation. The issue of the most appropriate treatment for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease has long been a subject of disagreement between surgeons and gastroenterologists. However, most would agree that a single management strategy is unlikely to be appropriate for all patients. Equally, there is a need for better comparative data for medical versus surgical therapy. Eight randomised trials19,27–39 have been reported that have investigated this issue, but five of these were completed or commenced before the availability of both laparoscopic antireflux surgery and proton-pump inhibitor medication. All of these trials recruited patients who had reflux symptoms that were well controlled by medical therapy. In the latter trials this entailed complete symptom control with a proton-pump inhibitor at trial commencement, thereby excluding patients with uncontrolled symptoms. Hence, the majority of patients who are currently selected for surgery were excluded from the surgical arms of these trials, i.e. patients with a poor response to a proton-pump inhibitor. In 1992, Spechler28 reported a trial of 247 patients (predominantly men) randomised to either continuous medical therapy with an H2 blocker, medical therapy for symptoms only or an open Nissen fundoplication. Overall patient satisfaction was highest following surgery at 1 and 2 years follow-up. However, neither the surgical nor medical treatment investigated is now considered optimal. The longer-term outcomes from this study were published in 2001, with median follow-up of approximately 7 years and with proton-pump inhibitors now used for the medically treated patients.40 Follow-up was not complete and only 37 (45%) surgical patients were available for late follow-up, with 23% of the original surgical group lost to follow-up, and 32% died during follow-up. The later results did, however, show reasonable outcomes in both the medically and surgically treated groups. However, 62% of the surgical patients consumed antireflux medications at late follow-up, although when these medications were ceased in both study groups the surgical group had significantly fewer reflux symptoms than the medical group, suggesting that most of the surgical patients did not actually need the medications! In 2003, Parrilla et al.29 reported a randomised trial that randomised 101 patients with Barrett’s oesophagus. Medical therapy was initially an H2 blocker and later a proton-pump inhibitor. A satisfactory clinical outcome was achieved at 5 years follow-up in 91% of each group, although medical treatment was associated with a poorer endoscopic outcome. Progression to dysplasia was similar in both groups. In 2000, Lundell et al.30,31,39 reported a trial of proton-pump inhibitor medication versus open antireflux surgery. Three hundred and ten patients were randomised, and antireflux surgery achieved a better outcome at up to 3 years follow-up. Later reports of 7 years follow-up in 228 patients, and 12 years follow-up in 124, confirmed that surgery still achieved better reflux control than medication, although dysphagia and various wind-related side-effects were more common after fundoplication.39,41 Rhodes et al. reported the first randomised trial to compare proton-pump inhibitor medication with laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication; 217 patients were enrolled. Surgery was followed by less oesophageal acid exposure 3 months after treatment and better symptom control at 12 months.32,33,42 A similar study by Anvari et al. enrolled 104 patients into a trial of proton-pump inhibitor therapy versus laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication.34–36 Follow-up at 12 months and 3 years demonstrated better control of reflux and better quality of life in the patients who underwent surgery. In 2009, Lundell et al.37 reported the outcomes for a further multicentre randomised trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication versus esomeprazole proton-pump inhibitor therapy (20–40 mg per day). This trial, which was funded by the pharmaceutical company that provided the medical therapy, enrolled 554 patients and outcomes at up to 3 years have been reported. Similar success rates of approximately 90% were reported for each treatment. The main disadvantage is operative morbidity (see discussion of complications). Laparoscopic surgery has greatly reduced the pain associated with open surgery; however, most patients experience some difficulty in swallowing in the immediate postoperative period, albeit temporary for the majority.43 The time taken to improve is variable, often several months.5 Furthermore, most patients experience early satiety leading to postoperative weight loss.5 In the patients who are overweight at the time of surgery (the majority!) this may be seen as an advantage. This restriction on meal size also usually disappears over a few months. Fundoplication produces a one-way valve; thus, patients have to be forewarned that they may not be able to belch effectively after the operation, especially in the first 6–12 months after surgery, and hence they should be cautious about drinking gassy drinks.44 This applies particularly to patients who undergo a Nissen (total) fundoplication. For similar reasons, patients will be unable to vomit after an effective procedure, and should be informed of this. Failure to belch swallowed gas leads to increased passage of flatus after the procedure.45 Patients who undergo a partial fundoplication (particularly anterior) have a lower incidence of these problems.4 Despite these negative sequelae, the overwhelming majority of patients claim that the disadvantages are far outweighed by the advantages of the operation.4,43,46 To date it has not been possible to predict preoperatively those patients who will develop problems following surgery. Endoscopy is essential. It enables oesophagitis to be documented (confirming reflux disease), strictures to be dilated, and other gastro-oesophageal pathology to be excluded, documented and treated. The position of the squamocolumnar junction and the presence and size of any hiatus hernia is also assessed. The presence of a large hiatus hernia is not a contraindication to a laparoscopic approach, although the surgery is technically more difficult.47 While many surgeons advocate the routine assessment of patients with 24-hour ambulatory pH monitoring before antireflux surgery, we use a selective approach. This test is not sufficiently accurate to be regarded as the ‘gold standard’ for the investigation of reflux, and if an abnormal pH profile is used to select patients for surgery, up to 20% of patients who have oesophagitis and typical reflux symptoms will be excluded unnecessarily from antireflux surgery. Hence, we apply this investigation in patients with endoscopy-negative reflux disease and in patients with atypical symptoms.14 This test’s ability to clarify whether symptoms are associated with reflux events is useful. The role of bile reflux monitoring remains undefined in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, although it has been suggested that it may be helpful in patients who fail to respond to acid suppression. This is measured using either ‘Bilitec’ or multichannel intraluminal impedance (MII) monitoring. ‘Bilitec’ measures intra-oesophageal bilirubin as an indirect marker of duodeno-oesophageal reflux, but has largely been superseded by MII, which measures ‘volume’ reflux. However, at this time, MII has only a limited role in the selection of patients for surgery.15 Total fundoplications, such as the Nissen, or partial fundoplications, whether anterior or posterior, probably all work in a similar fashion.8,57 The mechanisms of action of an antireflux operation are not completely clear; they may work as much in a mechanical as physiological fashion, as these procedures are effective not only when placed in the chest in vivo,58 but also on the benchtop, i.e. ex vivo.8 Some of the proposed mechanisms include: 1. The creation of a floppy valve by maintaining close apposition between the abdominal oesophagus and the gastric fundus. As intragastric pressure rises the intra-abdominal oesophagus is compressed by the adjacent fundus. 2. Exaggeration of the flap valve at the angle of His. 3. Increase in the basal pressure generated by the lower oesophageal sphincter. 4. Reduction in the triggering of transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations. 5. Reduction in the capacity of the gastric fundus, thereby speeding proximal and total gastric emptying. 6. Prevention of effacement of the lower oesophagus (which effectively weakens the lower sphincter). Since the procedures seem to work, even ex vivo,8 it seems likely that the first two mechanisms account for the efficacy of the majority of antireflux procedures. Equally, the increase in lower oesophageal sphincter pressure following surgery is not important, and in some partial fundoplication procedures there is very little increase in pressure, yet reflux is well controlled.4,59 The trend towards increasingly looser and shorter total fundoplications or greater use of partial fundoplication procedures suggests that there is no such thing as a fundoplication that is ‘too loose’. As ever, when there are a variety of different operations performed for the same underlying condition, this denotes that no single procedure yields perfect results, i.e. 100% reflux control with minimal side-effects. All techniques have their advocates. Published reports can be found that support every known procedure, and it is probably better to consider results from randomised trials when assessing the merits of these procedural variants (see below) rather than relying on uncontrolled outcomes reported by advocates of a single procedure. Equally, the experience of the operating surgeon is of great importance for achieving a good postoperative outcome.60 Variability can be reduced, but not eliminated, by detailed technical descriptions and effective surgical training. Over the last 20 years, a minimally invasive laparoscopic approach has become standard for primary antireflux surgery, making surgery more acceptable to patients and their physicians. Nissen fundoplication (Figs 13.1 and 13.2): Nissen originally described a procedure that entailed mobilisation of the oesophagus from the diaphragmatic hiatus, reduction of any hiatus hernia into the abdominal cavity, preservation of the vagus nerves and mobilisation of the posterior gastric fundus around behind the oesophagus, without dividing the short gastric vessels, and suturing of the posterior fundus to the anterior wall of the fundus using non-absorbable sutures, thereby achieving a complete wrap of stomach around the intra-abdominal oesophagus.61 The original fundoplication was 5 cm in length and an oesophageal bougie was not used to calibrate the wrap. This is now the commonest antireflux operation performed worldwide. Controversy still exists about the need to divide the short gastric vessels to achieve full fundal mobilisation. The so-called floppy Nissen procedure described by Donahue and Bombeck64 relies on extensive fundal mobilisation. On the other hand, the modification of the Nissen fundoplication using the anterior fundal wall alone, also first described by Nissen and Rossetti,61,65 does not require short gastric vessel division to construct the fundoplication. This simplifies the dissection, although more judgment and experience may be required to select the correct piece of stomach to use for the construction of a sufficiently loose fundoplication. Both procedures have their advocates, and good results (90% good or excellent long-term outcome) have been reported for both variants.62,65 Nevertheless, strong opinions are held about whether the short gastric vessels should be divided or not, and this controversy has been heightened by the introduction of laparoscopic fundoplication. Posterior partial fundoplication (Fig. 13.3): A variety of fundoplication operations have been described in which the fundus is wrapped partially round the back of the oesophagus, with the aim of reduction of the possible side-effects of total fundoplication due to overcompetence of the cardia, i.e. dysphagia and gas-related problems. Toupet described a posterior partial fundoplication in which the fundus is passed behind the oesophagus and sutured to the left lateral and right lateral walls of the oesophagus, as well as to the right diaphragmatic pillar, creating a 270° posterior fundoplication.66 A very similar procedure was described by Lind et al.67 This entails a 300° posterior fundoplication, which is constructed by suturing the fundus to the oesophagus at the left and right lateral positions, and additionally anteriorly on the left, leaving a 60° arc of oesophageal wall uncovered. The hiatus is repaired if necessary. Anterior partial fundoplication: Several anterior partial fundoplication procedures have been described, and all purport to reduce the incidence of dysphagia and other side-effects. The Belsey Mark IV procedure, popular in thoracic practice up the early 1990s, entails a 240° anterior partial fundoplication that is usually performed through a left thoracotomy approach.68 The distal oesophagus is mobilised, sutured to the gastric fundus and sutured to the diaphragm. Any hiatus hernia is repaired, and the anterior two-thirds of the abdominal oesophagus is covered by the fundoplication. The open thoracic access required is associated with significant morbidity, and for this reason it has fallen from favour since the arrival of laparoscopic antireflux surgery. A minimally invasive thoracoscopic approach was described 15 years ago,69 although clinical outcomes have never been reported, and this procedure is rarely performed. The Dor procedure is an anterior hemifundoplication that involves suturing of the fundus to the left and right sides of the oesophagus.70 The Dor procedure is commonly used in combination with an abdominal cardiomyotomy for achalasia as it is unlikely to cause dysphagia, and it may reduce the risk of gastro-oesophageal reflux following cardiomyotomy. A 120° anterior fundoplication has also been described.59 This entails reduction of any hiatus hernia, posterior hiatal repair, suture of the posterior oesophagus to the hiatal pillars posteriorly, suture of the fundus to the diaphragm to accentuate the angle of His, and creation of an anterior partial fundoplication by suturing the fundus to the oesophagus on the right anterolateral aspect. Satisfactory medium-term reflux control following open surgery has been reported for this procedure, and a low incidence of gas-related problems. However, published laparoscopic experience is more limited. We have reported the results from prospective randomised trials of laparoscopic anterior 180° partial fundoplication and laparoscopic anterior 90° partial fundoplication versus a Nissen procedure4,71–75 (see below). The anterior 180° fundoplication procedure entails hiatal repair, suture of the distal oesophagus to the hiatus posteriorly, and construction of an anterior fundoplication that is sutured to the oesophagus and the hiatal rim on the right and anteriorly (Figs 13.4 and 13.5). The anterior 90° partial fundoplication procedure entails hiatal repair, posterior oesophagopexy, narrowing of the angle of His and construction of a limited anterior fundoplication that covers the left anterolateral aspect of the oesophagus (Fig. 13.6). These variants of anterior fundoplication show promise. Figure 13.4 One-hundred-and-eighty-degree anterior partial fundoplication performed by the transabdominal route. Hill procedure: Hill described a procedure that is often regarded as a gastropexy rather than a fundoplication.76 However, it also plicates the cardia and when examined endoscopically the intragastric appearances are similar to a fundoplication. The procedure entails suturing the anterior and posterior phreno-oesophageal bundles to the pre-aortic fascia and the median arcuate ligament. Whilst excellent results have been reported by Hill and colleagues,77 it has not been applied widely because most surgeons have difficulty understanding the anatomical principles and, in particular, the phreno-oesophageal bundles are not clear structures. Hill also emphasises the need for intraoperative manometry. This is not widely available, limiting the dissemination of his technique. Collis procedure (Fig. 13.7): The Collis procedure is useful for patients whose oesophagogastric junction cannot be reduced below the diaphragm.78 However, this situation is very rare in current practice. The Collis procedure entails the construction of a tube of gastric lesser curve to recreate an abdominal length of oesophagus, around which a fundoplication can then be constructed to help with oesophageal shortening. It is often constructed by using a circular end-to-end stapler to create a transgastric window; a linear cutting stapler is used from this hole up to the angle of His to construct the neo-oesophagus. Laparoscopic and thoracoscopic techniques for this procedure have been described, although longer-term outcomes are not available.79,80 A disadvantage of this procedure is that the gastric tube does not have peristaltic activity and furthermore it can secrete acid. This leads to a poorer overall success rate for this procedure, although some of this could be due to the end-stage nature of the reflux disease that led to the choice of this procedure in the first place. Augmentation of the lower oesophageal sphincter: LINX®: In 2010, Bonavina et al.81 described a new approach to surgery for gastro-oesophageal reflux that entailed augmentation of the lower oesophageal sphincter with an implantable string of interlinked titanium beads with magnetic cores. This device (LINX Reflux Management System, Torax Medical, Shoreview, MN) is placed laparoscopically around the gastro-oesophageal junction, and aims to control reflux, but still allow normal swallowing and belching. Experience is limited to a case series of 44 patients followed for up to 2 years.81 A success rate of approximately 90%, as measured by both clinical scores and pH monitoring, has been reported, and this appears similar to the success rate following fundoplication. It is easy to place, so the potential benefits in comparison to standard Nissen are a standard approach and the relative lack of hiatal dissection. Clinicians familiar with the Angelchik prosthesis will be wary of placing a foreign body around the distal oesophagus, although placement appears to be safe. The outcomes of larger series and longer-term randomised comparative trials are required to prove clinical and cost-effectiveness before this procedures enters wide clinical practice.82 EndoStim®: Based on the premise of a dysfunctional sphincter, an innovative new approach to the management of GORD uses an implantable system to deliver electrical stimulation to the lower oesophageal sphincter in order to normalise its function and prevent acid reflux. The EndoStim® device is commercially available in the UK (CE-mark approved). A laparoscopic technique is used to implant the system’s electrodes into the distal oesophageal muscle layers using minimal hiatal dissection. A wirelessly programmable pacemaker is then placed subcutaneously. It is thought that the avoidance of a ‘wrap’ will reduce the negative sequelae associated with various fundoplications. Also, the electrical stimulation is ‘tailored’ to the individual patient’s GORD profile in terms of the number and timing of impulses. Initial data are promising when placed in patients at least partially responsive to proton-pump inhibition, with hiatal hernia ≤ 3 cm and only mild to moderate oesophagitis. Most importantly, implantation and electrical stimulation were safe. However, a well-designed, randomised, sham-control trial is needed to validate this approach.83 Complete or partial fundoplication? Many prospective randomised trials of Nissen versus a partial fundoplication have been performed. DeMeester et al.84 had the distinction of reporting the first randomised study in the field of surgery for reflux disease in 1974. Their trial randomised 45 patients to undergo either a Nissen, Hill or Belsey procedure, and they followed up their patients for 6 months after surgery. The dysphagia and recurrent reflux rates were similar for all three procedures. However, the number of patients was too small to allow a meaningful comparison to be made. Eleven randomised trials have compared a Nissen with a posterior partial fundoplication. Some of the trials contribute little to the pool of evidence as they are either small and underpowered, or only reported very-short-term outcomes.53,85–88 Lundell et al.89 reported the outcomes of the first large trial of Nissen versus a posterior (Toupet) partial fundoplication; 137 patients were enrolled. The early outcomes at 6 months follow-up were similar. At 5 years follow-up90 reflux control and dysphagia rates were also similar, although flatulence was commoner after Nissen fundoplication at 2 and 3 years but not at 4 or 5 years follow-up. Re-operation was more common following Nissen fundoplication, with one patient in the posterior fundoplication group undergoing further surgery for severe gas bloat symptoms and five of the Nissen group undergoing re-operation for postoperative paraoesophageal herniation. A reanalysis of the data from this trial45 sought to answer the question of whether a tailored approach to antireflux surgery should be applied. There were no demonstrable disadvantages for the Nissen procedure in those patients who had manometrically abnormal peristalsis before surgery. In 2011, minimum follow-up of 18 years was reported.91 The outcomes at this very late follow-up were equivalent, with success rates of more than 80% reported for both procedures, and no significant differences in the incidence of side-effects at late follow-up, suggesting that the mechanical side-effects following Nissen fundoplication improve progressively with very-long-term follow-up. Zornig et al.92 reported a trial that enrolled 200 patients to either total fundoplication with division of the short gastric vessels or posterior fundoplication. One hundred patients had normal preoperative oesophageal motility and 100 had ‘abnormal’ motility. At 4 months follow-up an overall good outcome was obtained in about 90% of patients in each group, and reflux control was equivalent. Short-term dysphagia was less common following posterior partial fundoplication, and no correlation was seen between preoperative oesophageal motility and outcome, providing no support for the selective application of a partial fundoplication in patients with abnormal preoperative motility. The 2-year follow-up outcomes were similar.55 Eighty-five per cent of each group were satisfied with their clinical outcome, and dysphagia remained significantly more common after Nissen fundoplication (19 vs. 8 patients). A study by Guérin et al.93 enrolled 140 patients. At 3 years follow-up 118 patients were evaluated and no outcome differences could be identified. Similarly, Booth et al.54 enrolled 127 patients in a trial of Nissen versus Toupet fundoplication, Khan et al.94 enrolled 121 patients in another trial, and Shaw et al.95 enrolled 100. Each of these trials showed no differences in reflux control 1 year after surgery. Although dysphagia was more common following Nissen fundoplication in Booth et al.’s trial, there were no differences in the prevalence of side-effects in the other trials. Subgroup analysis in Booth et al.’s and Shaw et al.’s trials did not reveal any differences between patients with or without poor preoperative oesophageal motility. Six trials have evaluated Nissen versus anterior partial fundoplication. In 1999 we reported the first prospective randomised trial to compare a Nissen fundoplication with an anterior partial fundoplication technique.4 Both procedures were performed laparoscopically. This study enrolled 107 patients to undergo either a Nissen or anterior partial fundoplication. The partial fundoplication variant entailed a 180° fundoplication that was anchored to the right hiatal pillar and the oesophageal wall (Figs 13.4 and 13.5). Whilst no overall outcome differences between the two procedures were demonstrated at 1 and 3 months follow-up, at 6 months patients who underwent an anterior fundoplication were less likely to experience dysphagia for solid food, were less likely to be troubled by excessive passage of flatus, were more likely to be able to belch normally, and the overall outcome was better. The outcomes at 5 years confirmed the results of the initial report.71 Reflux control was slightly better after Nissen fundoplication, but this was offset by significantly less dysphagia, less abdominal bloating and better preservation of belching, resulting in a greater proportion of patients reporting a good or excellent overall outcome 5 years after anterior fundoplication (94% vs. 86%). At 10 years follow-up, however, there were no significant outcome differences for the two procedures, with equivalent control of reflux, and no differences for side-effects,74 a similar outcome to the very late follow-up for the Lundell and colleagues, trial of Nissen versus posterior partial fundoplication.91 Baigrie et al.96 reported 2-year follow-up from a similar study in which 161 patients underwent either a Nissen or anterior 180° partial fundoplication. This trial demonstrated equivalent control of reflux symptoms and less dysphagia following anterior 180° partial fundoplication, although the incidence of re-operation for recurrent reflux was higher after anterior fundoplication. Cao et al.97 reported 5-year outcomes for a similar trial that enrolled 100 patients. Reflux control was similar for the two procedures, and flatulence was less common after anterior 180° partial fundoplication. Raue et al.98 reported equivalent outcomes at 18 months mean follow-up in a smaller trial that enrolled 64 patients. Two further trials have compared a laparoscopic anterior 90° partial fundoplication with a Nissen fundoplication. In the first of these, 112 patients were enrolled in a multicentre randomised trial conducted in six cities in Australia and New Zealand.72,75 Side-effects were significantly less common following anterior 90° fundoplication, although this was offset by a slightly higher incidence of recurrent reflux at 6 months follow-up.72 At 5 years the outcomes were similar for side-effects, although reflux was worse after the partial fundoplication.75 Satisfaction with the overall outcome was similar for both fundoplication types. Similar outcomes were reported from a parallel single-centre randomised trial that enrolled 79 patients – fewer side-effects offset by more reflux.73 Two randomised trials have directly compared anterior versus posterior partial fundoplication. Hagedorn et al.99–101 randomised 95 patients to undergo either a laparoscopic posterior (Toupet) or anterior 120° partial fundoplication. Their results showed better reflux control, but more side-effects following posterior partial fundoplication. Unfortunately, the clinical and objective outcomes following anterior 120° fundoplication in this trial were much worse than the outcomes from other randomised and non- randomised studies. The average exposure time to acid (pH < 4) was 5.6% following anterior fundoplication in their study, whereas in other studies this figure is reported to be between 2.5% and 2.7%,4,72 suggesting that the procedure performed in the study of Hagedorn et al. was less effective and therefore different to the procedures performed in other studies. More recently, Khan et al.102 reported 6 months follow-up from a trial that enrolled 103 patients to undergo anterior 180° versus posterior partial fundoplication. Reflux control was also better after posterior partial fundoplication, but offset by more side-effects.

Treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

Introduction

Medical treatment

H2-receptor antagonists

Proton-pump inhibitors

Prokinetic agents

Surgical treatment

Selection criteria for surgery

Patients with complicated reflux disease

Patients with uncomplicated reflux disease

Medical versus surgical therapy

Pros and cons of antireflux surgery

Disadvantages

Preoperative investigations

Endoscopy

Oesophageal pH monitoring

Other investigations

Antireflux surgery

Mechanisms of action of antireflux surgery

Techniques of antireflux surgery

Other antireflux procedures

Controversies and comparisons

Nissen versus posterior fundoplication

Nissen versus anterior fundoplication

Anterior versus posterior partial fundoplication

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease