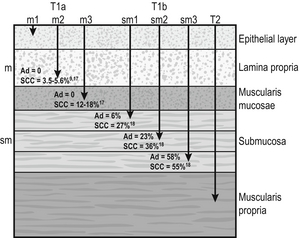

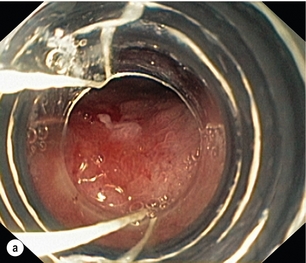

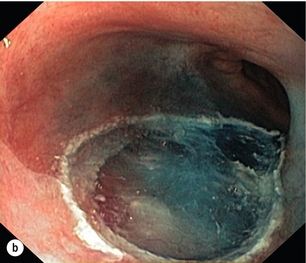

6 A cancer in the oesophagus is considered ‘early’ if it is contained within the superficial components of the epithelial lining and there is no lymph node involvement. Using the latest American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging criteria, for both SCC and AC, this would include oesophageal cancer diagnosed at stages 0 or IA.1 Stage 0 includes Tis or high-grade dysplasia (HGD) of the epithelium. This had previously been called carcinoma in situ.2 Stage I relates to the depth of invasion into the oesophageal wall with no lymph nodes involved. This stage includes cancers that are T1–2. However, the pathological stage can only be diagnosed after the resection of the oesophagus. The deeper the invasion into the mucosa and submucosa, the higher the incidence of nodal metastasis, so that a clear definition of the T stage is vital when assessing a patient thought to have an ‘early’ oesophageal cancer. The T stage can be subclassified into cancer that is restricted to the mucosa, T1a, and to the submucosa, T1b. Within the mucosa (T1a) the invasion can be subclassified into cancers confined to the epithelium (m1), the lamina propria (m2) and the muscularis mucosae (m3).1 Patients with Barrett’s oesophagus may have duplication of the muscularis mucosae but they are still m3 so long as the muscularis mucosae has not been breached. Cancers infiltrating into the submucosa (T1b) may be subclassified into sm1 (inner third), sm2 (middle third) and sm3 (outer third)1 (Fig. 6.1). Figure 6.1 Anatomical layers of the oesophagus with risk of lymph node involvement. Ad, adenocarcinoma. The relevance of subclassification relates to the risk of lymphatic invasion. The lymphatic network in the oesophagus is concentrated in the submucosa; however, there are lymphatic channels in the lamina propria. From studies of patients that have had a resection for T1 cancer it is clear that there is a higher risk of nodal involvement if it invades to T1b level compared with T1a cancers.3–17 There are subtle differences between patients with AC and SCC. HGD in Barrett’s epithelium and in squamous epithelium as well as AC or SCC involving m1 do not have nodal disease.3–5,10,11,13,17 AC invading to m2 and m3 do not have lymph node metastasis.3–6,8 However, for patients with SCC to the m2 level, there have been reports of patients with positive lymph nodes found in 3.3%9 and 5.6%,17 although this is not clear as others have reported no evidence of positive nodes at this level.10–15 If the tumour extends to m3, the node-positive rate has been reported to be 18% in a large single-centre series17 and 12.2% in a review of 1740 patients with early SCC.9 The histological finding of lymphatic invasion in association with m3 invasion has been shown to increase the risk of positive lymph nodes11,17 from 10% to 42%.17 For either AC or SCC invading the submucosa (T1b), the potential for nodal metastasis increases from sm1 to sm3.18 A review of articles from 1980 to 2009 reported an overall lymph node-positive rate of 37%, with the incidence higher for SCC (45%) than AC (26%). For sm1 disease, the presence of lymphatic invasion on histology increases the risk of positive lymph nodes from 11% to 65%.11 The incidence of node positivity was higher in patients with SCC compared with AC at sm1 (27% vs. 6%) and sm2 (36% vs. 23%) levels, but the same at sm3 (55% vs. 58%).18 The implication may be that SCC is more biologically aggressive at presentation. For patients with T1b cancers the optimal oncological therapy is an oesophagectomy with a systematic lymphadenectomy. There may be ‘low-risk’ sm1 patients with AC that might be considered for endoscopic therapies but it is not so clear for patients with SCC. The ‘low-risk’ AC is a patient with a well-differentiated cancer with no evidence of lymphovascular invasion.5,8 One report of 85 patients with T1 AC analysed four subgroups with differing nodal involvement and prognosis. Patients with T1a disease had no nodes and 100% disease-specific survival (DSS). Those with T1b cancers were split into three groups: well differentiated and no lymphatic/vascular invasion (LVI) – 4% nodal involvement, 85% 5-year DSS; poorly differentiated and no LVI – 22% nodal involvement, 65% 5-year DSS; and any cancer with LVI – 46% nodal involvement, 40% 5-year DSS.5 The reason for the difference between histological subtypes is not clear but explanations include: fewer lymphatic channels in the lamina propria in the lower oesophagus (where AC occurs7) and SCC is more biologically aggressive at an earlier stage.18 Patients with the diagnosis of HGD or intramucosal carcinoma in Barrett’s epithelium should have the endoscopy repeated according to a protocol of four quadrant biopsies 1 cm apart and targeted biopsies of macroscopically suspect lesions.19 The pathology should be reviewed by two independent experienced gastrointestinal pathologists to confirm the diagnosis. Patients with a diagnosis of HGD in squamous epithelium or suspected early invasive carcinoma should have the endoscopy repeated to clearly establish the extent of the disease process. The use of Lugol’s iodine staining is recommended to allow targeted biopsies of the non-stained areas.20 Knowledge of the extent of the mucosal change is important when planning treatment as very long segments may only be treated with oesophagectomy. If endoscopic therapy is to be considered, the non-stained areas outline the targets for endoscopic resection or ablation. This is the removal of the mucosa and a varying degree of submucosa. In patients with HGD or suspected intramucosal carcinoma (IMC) this is the most accurate and definitive method of confirming the histology and defining the T stage of abnormal mucosa or any mucosal lesion.21,22 Endoscopic mucosal resection offers better T staging than endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and computed tomography (CT) scanning,23 and will alter the histological grade or the local T stage of mucosal neoplasia in up to 48% of patients,24 thereby potentially influencing the management (Fig. 6.2). Figure 6.2 Intramucosal carcinoma in a segment of Barrett’s epithelium before (a) and after (b) endoscopic mucosal resection. Patients with squamous epithelial neoplasia can have abnormailites targeted with EMR. A study of 51 patients who had an EMR for squamous HGD reported 31% to be m2/3, with over a third of these lesions being flat such that they were unrecognisable from HGD alone.25 This also stresses the need for extensive mapping biopsies of squamous epithelial neoplasia, using Lugol’s iodine, if endoscopic therapies are to be considered. This technique is widely used in Asia, notably by the Japanese, for definitive treatment of patients with superficial gastric cancer. It has been used for squamous neoplasia because it entails a formal dissection in the submucosal plane to remove a complete segment of mucosa and submucosa. The advantage is that the whole abnormal segment of oesophagus may be removed en bloc26,27 and there is less likelihood of margins being involved when compared with EMR in the tubular oesophagus.26,28 The accuracy of differentiating the layers of the mucosa has been reported to be 85–100% with the use of the higher frequency (15 and 20 MHz) miniprobes;29 however, the numbers are small and these are expert centres. In general practice this differentiation is not good enough to stratify patients to allow decisions relating to endoscopic therapy and oesophagectomy.6 It may be the value of EUS will be for examination of the local lymph nodes and, if considered suspicious, achieving confirmation with fine-needle aspiration.29 When the tumour is considered to be invasive there is a role for anatomical imaging with CT scanning and functional imaging with positron emission tomography (PET) for formal staging.30 In a review from 2007 of 29 series of patients having a resection for Barrett’s HGD, it was reported that cancer was found in the specimen in 37% of cases with 60% of this group (22% of the total) invading beyond the mucosa.31 They reported no downward trend in this incidence in recent years. This review consists of a number of older series where patients were not likely to have had a systematic approach to biopsy of the Barrett’s mucosa, and none of the patients underwent an EMR of abnormal mucosa, which would offer a better histological assessment with improved T staging. The factors that have been reported to be associated with a coexisting cancer in HGD are a visible lesion, ulceration and HGD at multiple levels.32,33 The potential for an unexpected finding of an invasive cancer is now lower than previously reported. For patients confirmed to have squamous dysplasia the potential for the development of an invasive cancer increases with time. For low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (LGIN), the risk at 3.5 and 13.5 years has been reported as 5% and 24%, respectively, for moderate-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (MGIN) 27% and 50%, respectively, and for high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (HGIN) 65% and 74%, respectively.34 Definitive treatment should be directed towards HGD with careful observation in patients with lower levels of dysplasia. Although patients with HGD do not have an invasive cancer the risk is removed completely with an oesophagectomy. In the short term the potential for short-term cancer mortality is very low, so it is important that the surgical outcomes are optimal. In the last decade operative mortality for oesophageal resection in high-volume centres has been reported to be 2–4%, with rates of 0–1% when the resection was for HGD or IMC.31,35 The long-term disease-specific survival (DSS) following an oesophagectomy for HGD should be 100% and for early invasive oesophageal cancer (stage I) for AC 80–90%7,36 and SCC 3-year survival of 85%37 and 5-year DSS of 53–77%38,39 have been reported. Because of the associated high morbidity, mortality and effects on the quality of life, alternatives to a traditional oesophagectomy and lymphadenectomy have been explored. For lesser procedures to be successful a degree of predictability of the lymph node drainage is necessary. For stage I disease, in one study, patients with AC had the majority of positive nodes below the tracheal bifurcation, locally associated with the primary cancer in all but 2%. For SCC the nodal site was not predicable, with the positive nodes widely distributed in the chest and upper abdomen.7 Thus, for early AC this had led to groups attempting variations from a major resection. Two variations described for patients with Barrett’s HGD and IMC are a limited resection of the oesophagogastric junction40 and vagal-sparing oesophagectomy.41 The resection of the oesophagogastric junction with jejunal interposition (Merendino operation) is performed using a transabdominal approach, with splitting of the oesophageal hiatus. The dissection can be carried out, through the hiatus, to the level of the tracheal bifurcation incorporating a lower mediastinal and upper abdominal lymphadenectomy with or without preservation of the vagal innervation of the distal stomach. Following resection of the distal oesophagus, cardia and proximal stomach, the gastrointestinal continuity is restored by means of interposition of an isoperistaltic pedicled jejunal loop to prevent postoperative reflux.40 The outcome of over 100 procedures for early Barrett’s cancer reported similar outcomes in terms of long-term survival compared with a radical oesophagectomy. The advantages were lower peri- and postoperative morbidity, and a good postoperative quality of life. The procedure has been reported to be technically challenging and requires attention to detail to achieve good long-term functional results.40 Vagal-sparing oesophagectomy (VSO) has recently been popularised for HGD and T1a adenocarcinoma of the lower oesophagus. Reconstruction is via the use of a gastric tube or colon pull-up. The authors report a reduction in side-effects attributed to the vagal resection that occurs with a more aggressive resection.41 The operative mortality has been reported to be 2% with major complications in 35% of patients, but there was a reduction, but not abolition, of diarrhoea and dumping symptoms.41 Alternative approaches are the transhiatal approach and minimally invasive approaches to an oesophageal resection. The transhiatal approach has been reported to reduce respiratory complications compared with an open oesophagectomy.42,43 Although suitable for AC the transhiatal approach does not address the issue of the unpredictable lymphatic drainage of SCC, so that a systematic lymphadenectomy should be performed with the benefits of an upper and cervical mediastinal lymphadenectomy being weighed against the added morbidity.7,10,44 Minimally invasive approaches to oesophagectomy will allow resection of the primary cancer and a lymphadenectomy. Reports suggest there may be a reduction in respiratory complications when the chest and abdominal components are performed using minimally invasive approaches.45–47 The approach has also been described allowing a dissection of the mediastinum, as required for SCC.48 Oesophagectomy does have an effect on the quality of life of patients. There have been reports that claim the long-term functional outcomes from a resection are at least equivalent to the general population.49,50 However, despite their conclusions there are patients that have significant gastro-oesophageal reflux (59–68%), dysphagia (38%), dumping (15%), diarrhoea (55%) and bloating (45%).49,50 Others have confirmed the higher incidences of functional symptoms such as dumping syndrome, bloat, reflux and diarrhoea, which do not settle in the long term.51 Aside from diagnosis and T-stage assessment this technique may be therapeutic, removing the lesion completely. The techniques used for this procedure result in piecemeal segments of mucosa and submucosa being removed. Techniques such as ‘inject, suck and cut’(endoscopic resection cap, ER-cap) and ‘band and snare’ (endoscopic resection multiband mucosectomy, ER-MBM) are used, and have been shown to provide the pathologist with equivalent and adequate depths of mucosa and submucosa.52 A randomised study assessing the two techniques has shown that ER-cap produces specimens of larger diameter but with equivalent amount of submucosa. ER-MBM was quicker, less costly and had a similar safety profile.53 Short segments of neoplastic epithelium (Barrett’s or squamous) can be completely removed in up to 80–94% of patients.54 The recurrence rate increases with the length of follow-up because the treatment may not deal with all the Barrett’s epithelium, some of which may not be visible.3 When EMR alone is used to eradicate the Barrett’s segment the complete eradication rate may reach 97%, but the incidence of stricture increases up to 37%.55 It is likely the optimal use of EMR will be in combination with Barrett’s ablative techniques. The technique has been shown to be safe, with a low incidence of complications such as bleeding (0–1.5%), perforation (0.3–0.5%) and stricture formation if segmental regions are treated (7–9%). For squamous epithelial neoplasia the results from EMR are similar to Barrett’s neoplasia, with rates of recurrence reported to be 10–26%.26,56,57 When examining the recurrence rate in association with depth of invasion, the incidence has been reported to be 13–18% in lesions that are m1/2.57

Treatment of early oesophageal cancer

Definition of early oesophageal cancer and relevant pathology

Investigations

Endoscopic assessment

Squamous neoplasia

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR)

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD)

Imaging

Management of early oesophageal cancer

Oesophageal resection

Endoscopic therapy

Endoscopic mucosal resection

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Treatment of early oesophageal cancer