Polycystic liver disease (PLD)

Liver Cell Adenoma (LCA) and Liver Adenomatosis (LA)

Hepatic Hemangioma (HH)

Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (HEHE)

Other infrequent solid nodules (hepatic hydatid disease; nodular regenerative hyperplasia; lymphangiomatosis of the liver, mesenchymal hamartoma, focal nodular hyperplasia; biliary cystadenoma)

Published reports are limited and based on small case series or single case report with a consequent lack of data regarding optimal indications for OLT in case of BHL. The transplant is doubtless the definitive and curative therapy, but considering the shortage of donor grafts, the high morbidity, and the mortality risk (estimated to be 1–3 %), this indication remains not standard in this population for whom conservative approach and, if necessary, surgical resection are the gold standard. OLT is a valid therapeutic option in the case of the conditions reported in Table 18.2.

Table 18.2

Clinical indications for OLT in case of BHL

Severe symptoms with discomfort for abdominal encumbrance |

Uncertain diagnosis or preneoplastic lesions |

Increased risk of life-threatening complications, rupture, or malignant transformation |

Lesions not amenable to resection due to wide diffusion in the hepatic parenchyma |

Hepatic function impairment |

Metabolic diseases and Kasabach–Merritt syndrome |

The European Register of Liver Transplants (ELTR) reports the data of 97,698 OLT carried out in the period 1988–2012 [3].

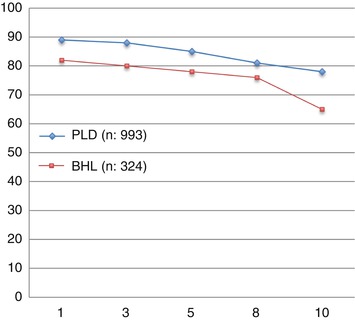

A total of 994 (1.01 %) OLT due to Polycystic liver disease (PLD) are carried out and 324 OLT (0.33 %) for other benign tumor lesions.

Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (HEHE) is instead classified to have a neoplastic etiology due to its borderline nature, and it represents 1.5 % of OLT performed for cancer (232/15,197) in the same period.

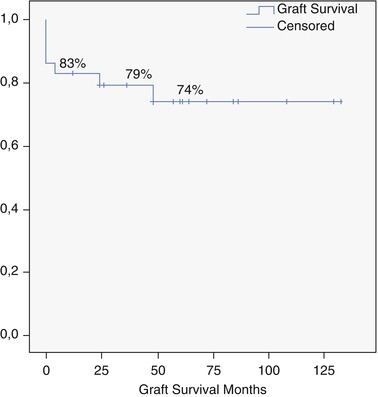

The survival rate of OLT performed in 1988–2012 for PLD and other benign liver lesions based on ELTR data is shown in Fig. 18.1.

Fig. 18.1

Survival (1–10 years) after OLT for all benign hepatic lesions and polycystic liver disease (ELTR data 1988–2012)

The incidence of transplants for hepatic benign nodular disease is roughly the same in United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) area (0.9 %) [4] and ELTR (1.3 %). Among the different benign nodular diseases, although it is a cystic and not a solid tumor, PLD is by far the most common: 78 % in the UNOS area and 75 % in the ELTR; it takes therefore a prominent place also for the implications of renal failure due to polycystic kidney disease.

18.1.1 The Ghent University Hospital Experience

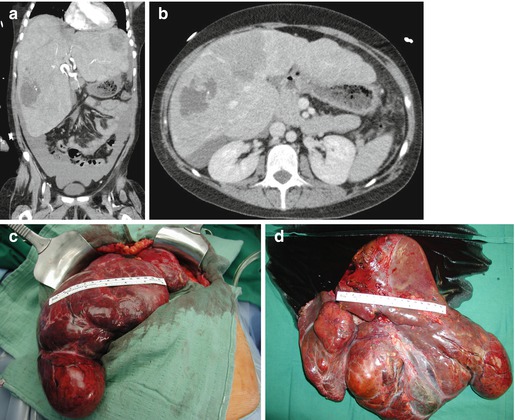

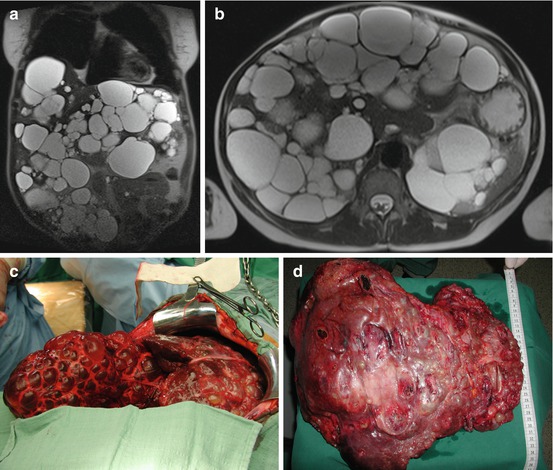

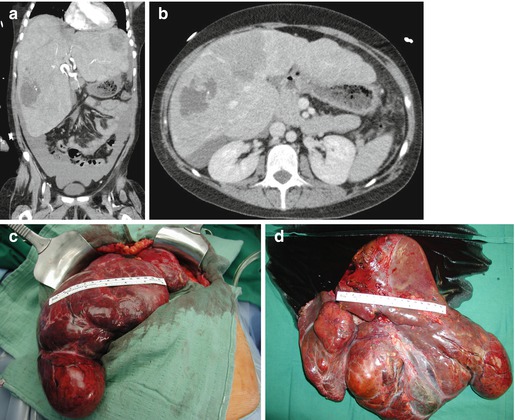

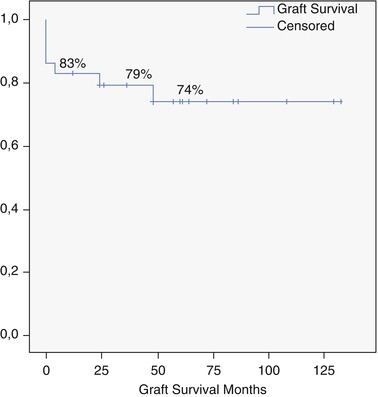

From 2002 to 2013, we performed 33 OLT for BLT (5.2 % of 633). PLD (Fig. 18.2) is the most common indication (29 pt; 87.8 %), and 7 (24.1 %) of these patients received combined liver kidney transplant (CLKT); other indications (3 pt; 9.1 %) were liver cell adenoma (LCA), liver adenomatosis (LA) (Fig. 18.3), and HEHE. The graft survival of OLT for PLD is reported in Fig. 18.4.

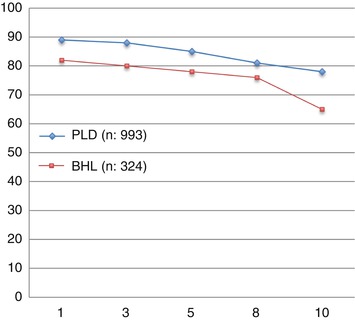

Fig. 18.2

(a–d) F 55 y.o. BMI 19. PLD in clinical follow-up (7 years). Impaired quality of life due to cachexia for severe malnutrition and recurrent cyst infection. MELD labo 13. Graft allocation: standard exception. OLT 9-1-2013. Donor: 53 y.o. intracerebral bleeding

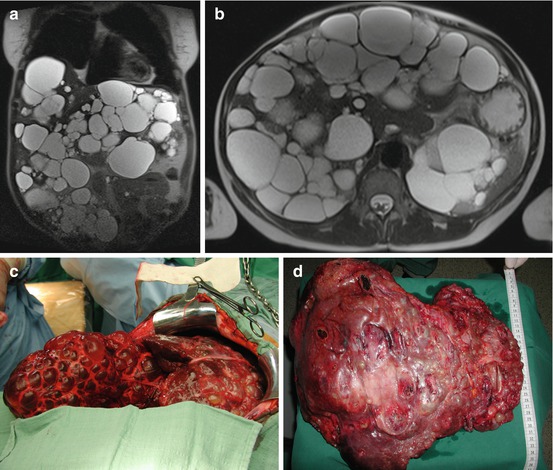

Fig. 18.3

(a–d) F 22 y.o. BMI 21. Maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 3. Liver adenomatosis in clinical follow-up (5 years) complicated by sudden hemoperitoneum due to spontaneous bleeding of the left lobe. MELD labo 9. Graft allocation: nonstandard exception. OLT 24-9-2013. Donor: F/63 y.o. intracranial bleeding. Native hepatectomy specimen: liver segments completely substituted by HNF1α non-activated adenomatous nodules

Fig. 18.4

Overall graft survival for PLD (Ghent University Hospital series)

Two living donor liver transplantations (LDLT) were performed for LA and PLD. The retransplantation rate is 15 % (5/33): one late re-OLT for biliary cirrhosis 4 years following the first OLT for PLD, three for early hepatic thrombosis, and the last for PNF. This last patient died 4 months after re-OLT due to septic complications.

The overall morbidity rate was of 33.3 % (11/33 pt), and this was concerning only patients transplanted for PLD.

Seven patients (21.2 %) had biliary anastomosis stricture after a mean of 4.2 months (range 3–6) post-OLT, and three were surgically treated. Hepatic artery thrombosis was recorded in four patients, three of them requiring urgent retransplantation.

18.2 Polycystic Liver Disease

PLD is a rare autosomal dominant benign disorder characterized by well-preserved liver function but can result in substantial morbidity, and this can increase mortality rates. Hepatic failure is uncommon, but quality of life (QoL) can be severely impaired with huge hepatomegaly causing abdominal distension accompanied with pain, dyspepsia or reduction of oral intake, malnutrition, weight loss, asthenia, dyspnea, and fatigue and physical and even psychological handicap. Symptoms develop when mass polycystic disease is already established or when the cyst/parenchyma ratio is above >1 [5].

Hepatic venous outflow impairment due to huge liver cysts causing a secondary Budd–Chiari syndrome for extrinsic compression of the hepatic veins and the inferior vena cava has been rarely reported also [6–8].

Although conservative therapy is the standard approach, in severe cases of PLD where conventional surgery (i.e., cyst fenestration) is not indicated [9], OLT might be considered.

The first OLT for PLD was a combined liver–kidney transplantation (CLKT) for massive organomegaly performed by Kwok and Lewin in 1988. Unfortunately, the patient died intraoperatively because of intractable bleeding [10]. Two years later, Starzl reported 4 CLKT in patients with polycystic disease with one patient died 5 months after transplantation [11].

Transplant can offer fully curative and radical treatment also if some controversies remain, considering the absence of liver failure, the relative organ shortage, the perioperative risks of mortality, and the need for lifelong immunosuppression. OLT should be considered as a valid therapeutic option in carefully selected patients with symptomatic PLD. Considering that the organ function is preserved until a late stage, the question of “when” the transplant is appropriate is challenging. Due to the absence of signs of liver failure, the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score is not representative for these patients. According to Arrazola et al. [12], patients with PLD should meet the criteria reported in Table 18.3 in order to be listed for LT.

Table 18.3

Criteria for listing patients with PLD for OLT

Massive PLD (total cyst/parenchyma ratio >1) |

Complication of the PLD that is likely to resolve after OLT |

Clinically significant manifestations of liver disease that can be attributed to massive PLD (cachexia, ascites, portal hypertension, hepatic venous outflow obstruction, biliary obstruction, cholestasis, or recurrent cyst infection) |

Not candidates for, or have disease that has failed to respond to, non-OLT interventions for relief of symptoms |

Contraindication to non-transplant surgery: severe malnutrition |

Hypoalbuminemia <2.2 mg/dL |

Decreased lean body mass: decreased midarm circumference, measured in the nondominant arm midway between the acromion and the olecranon process (<23.1 cm in female patients and <23.8 cm in male patients) |

In the MELD-driven system, he proposed that the eligibility for OLT should continue to be addressed by the regional review board in a case-by-case basis, suggesting that patients could be given 15 MELD points and MELD could be increased three points every 3 months [12].

The priority on the waiting list for patients with PLD is reasoned since results are clearly worse when OLT is delayed and malnutrition and severe compressive symptoms are present.

In the Eurotransplant area, the level of priority can be upgraded as standard exception after a waiting time of 12 months [12–14].

The unreliable representation by the MELD score, the increased perioperative risk in patients with severe cachexia and malnutrition, and the excellent long-term results after transplantation suggest the need for an earlier referral for transplantation.

The septic complications are indeed the main cause of a postoperative mortality up to 20–30 % of the earlier studies. The increased risk of sepsis might have been due to bacterial reservoirs in cysts and/or prolonged poor nutritional status, amplified by the immunosuppressive agents: it is therefore of paramount importance to adopt for these patients a tailored immunosuppressive regimen.

Except for this high postoperative risk, patients transplanted for PLD have a good long-term prognosis and excellent relief of symptoms, although in small case series [15].

In case of previous abdominal surgeries, a challenging total hepatectomy phase should be anticipated. According to the UNOS data, in 46 % of all PLD recipients surgical antecedents have been recorded [4]. Furthermore, the displacement of the vascular and biliary structures in the hilum alters the normal anatomical landmarks. In view of the encountered ntraoperative difficulties, iterative surgical approaches should be abandoned in favor of the more radical transplant procedure. Mainly the “wrapping” of the fenestrated parenchyma with omentum makes the transplant more difficult, hampering the subsequent OLT.

Laparoscopic cyst fenestration that leads to less morbidity compared to the open approach is strongly recommended in case of not numerous and huge cysts [9, 16, 17].

The best surgical approach during total hepatectomy is still under debate. Jiang et al. [18] sequential partial hepatectomy to reduce progressively the liver volume, while others believe this could involve a greater risk of hemorrhage. Cysts fenestration facilitates the IVC approach, reducing also hepatic venous congestion and subsequent bleeding. Considering that these are patients without severe portal hypertension, the portal vein is only clamped at the end of hepatectomy [18, 19].

In cases of PLKD, if the abovementioned symptoms are associated with renal failure requiring hemodialysis or with a glomerular filtration rate below 30 mL/min, CLKT is indicated. Indeed after OLT, the patients often get nephrotoxic calcineurin inhibitors as immunosuppressive agents, which often worsen the already deteriorated kidney function.

Liver cysts usually appear later than kidney cysts, often during the fourth or fifth decade of life [13, 20, 21].

The number and volume of renal cysts are correlated with age, severity of kidney disease, and decline of glomerular filtration rate. Structural and functional renal deterioration of polycystic disease is the fourth leading cause of end-stage renal failure in adults [22, 23].

For patients affected by a disease leading to both irreversible liver and kidney failures such as autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD), combined liver–kidney transplantation is indicated.

CLKT is a two-step procedure, in which whole or partial liver and kidney from a donor are transplanted to a recipient in the same operation. Since kidney and liver manifestations progress differently, an individualized management is of paramount importance, mostly in the pediatric patient population. Most often isolated kidney transplant (KT) is performed first, followed by OLT or CLKT later in childhood or adulthood. Sometimes PLD proceeds quite fast, and OLT or CLKT should be regarded as the first option.

Srinath and Schneider [24] reported a survey of 116 transplanted ARPKD patients: 56 % KT, 34 % OLT, and 9 % CLKT.

The decision about the correct timing and type of transplant may be challenging. When isolated KT is performed, hepatic disease can worsen the outcome, especially by increasing the risk for cholangitis and sepsis [25].

Moreover, the post-KT QoL of children with ARPKD often remains impaired due to the hepatomegaly and the infectious complications.

There are no guidelines for CLKT in ARPKD patients: the higher morbidity and mortality associated with post-CLKT with respect to KT alone seem to favor the isolated KT as the first option; on the other hand, refractory complications of recurrent sepsis from large and infected biliary dilatations suggest CLKT as the first option (Table 18.4).

Table 18.4

Indications for CLKT or isolated OLT in patients with ARPKD

Massive PLD (total cyst/parenchyma ratio >1) |

Impaired liver function (low synthetic capacity of the liver, hyperammonemia) |

Renal failure (hemodialysis or GFR <30 mL/m) |

Complications of portal hypertension (bleeding esophageal varices, splenomegaly and/or hypersplenism, refractory ascites) |

Complications of biliary tract dilatation (repeated episodes of cholangitis or chronic cholangitis, large biliary dilatations) |

Severe liver cirrhosis in biopsy |

“Severe” PKD1 mutations (truncating mutations) |

Simultaneous CLKT seems to provide better long-term kidney function than a sequential transplant [26].

Studies on adult patients report that recipients of simultaneous CKLT have a lower incidence of kidney rejection and allograft loss than patients with isolated KT or sequential transplantation [27].

According to the UNOS database, 21 % of adult CLKT patients had acute rejection episodes as compared to 30 % of patients with isolated KT [28, 29]. A suggestive hypothesis is that the liver “offers” immunological protection against rejection of the kidney graft, trapping with the Kupffer cells the preformed antibodies.

The study of Dar et al. [30] suggests that the liver may not be completely protective; preformed donor-specific antibodies seem to promote rejection as later confirmed in a large analysis [31] of over 2,484 CLKT recipients: pre-sensitization had a negative impact on survival of both the patient and the kidney graft.

The mechanism by which a liver simultaneously transplanted with a kidney would protect the kidney graft from rejection episodes, and prolonged renal allograft survival, is not known.

It has been suggested that CLKT results in microchimerism and donor-specific hyporesponsiveness. Soluble class I HLA antigens from the liver could neutralize cytotoxic T lymphocytes and anti-HLA antibodies. Similarly, regulatory HLA-G antigens produced by the liver might inhibit T-cell cytotoxicity [32].

Secretion by the liver of immunomodulatory cytokines has also been suggested. In a recent study of combined auxiliary liver–kidney transplantation, liver grafts strongly upregulated CCL20 lymphokine, which can recruit dendritic cells and regulatory T cells and thus prevent rejection [33].

Gedaly et al. [34] analyzed the data of the 357 OLT for PLD in the UNOS database from 1988 to 2010 (0.3 % of 107,411). A 10 % cohort of patients transplanted for a diagnosis other than PLD was randomly selected from the database and used as a comparison group. Perioperative mortality (<30 days) was higher in the PLD group (9 % vs 6 %), and survival was lower for the first months (P < 0.05). Infectious morbidity was the most common cause of death, but a significant number of patients died also from intra- or early postoperative bleeding.

A direct relationship was also found between death and recipient’s age showing that most patients dying in the early postoperative period were 69 years or older. At first year, the survival was the same to other diagnoses (85 %) and better at 3 (81 % vs 77 %) and 5 years (77 % vs 71 %; P = 0.006).

Recently, van Keimpema et al. [35] published the largest retrospective analysis from ELTR demonstrating excellent long-term survival in patients undergoing transplantation for PLD. They reported a 5-year survival of 87.5 % in a series of 58 patients.

Kirchner et al. [13] published the largest single-center experience in 36 patients with PLD. They reported an excellent survival of 86 % and confirmed that infectious complications are the most common cause of death in PLD patients after OLT.

Assilou et al. [36] reported 85 % 5-year survival rates in their 27 PLD OLT also confirming high morbidity and perioperative mortality (15 %).

Due to severe cachexia and/or septic complications, for an indication so special and circumscribed is of great importance an earlier selection of the affected patients in order to reduce perioperative mortality.

This is in contrast to the fact that patients often have a normal metabolic liver function and usually do not feel affected by life-threatening disease.

In the early stages of PLD, symptoms such as abdominal pain, malnutrition, or reduced physical fitness may not be convincing enough for the patient to accept the risk and complications of organ transplantation.

Early referral and transplantation should be advised as malnutrition is usually associated with poor survival after OLT. Besides long-term survival, the changes in QoL after OLT or CLKT need to be addressed.

18.2.1 Liver Hemangioma

The vast majority of hepatic hemangiomas (HH) are small and asymptomatic but can also occur as a large lesion that in case of diffuse hemangiomatosis may almost completely replace the hepatic parenchyma.

Surgical treatment is the first choice in huge symptomatic lesions or in HH rapidly growing. The risk of bleeding is mainly correlated with the size, the relationships with the hepatic veins, and the lifestyle of the patient.

Considering the large incidence of HH in the adult population with prevalence in autopsy and imaging studies, up to 7 % OLT is an absolutely exceptional indication and in highly selected patients [37–40].

OLT is often needed due to the development of the Kasabach–Merritt syndrome (KMS), also known as “hemangioma with thrombocytopenia” that presents coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, hypofibrinogenemia, and fibrinolysis [40–42].

A completely different clinical condition is the infant hepatic single or multiple hemangiomas (hemangiomatosis). The incidence of infant HH is around 4–5 % of all pediatric neoplasm, and it is usually asymptomatic and diagnosed incidentally [45].

Pediatric HH can involve the entire liver or reveals itself with a diffuse-type hemangioma associated with a greater risk of death due to serious symptoms and KMS may possibly arise. The first-line approach in patients with significant arteriovenous shunts is represented by steroid therapy. However, 10–20 % of patients are refractory to medical therapies and can develop hepatomegaly and life-threatening hepatic complications. In such cases, a more aggressive treatment including liver resection, hepatic artery embolization, and OLT should be considered. Kuroda et al. [46] published in 2014 a Japan nationwide survey for pediatric critical hemangioma proposing OLT as an appropriate option for both acute and chronic phases of this disease.

However, it remains one of the latest options, which have to be considered after medical therapy failure or as a rescue therapy in emergency settings.

As reported by Zhong et al. [47], the use of living donor graft is a valid option in this scenario. Indeed, Markiewicz et al. [45] reported four OLT in newborn patients due to acute hemodynamic decompensation caused by a giant hemangioma and unresponsive to all other conventional therapies; in three cases, a living donor graft was used and all patients were alive between 9 and 37 months at the time of publication.

18.3 Hepatic Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma

Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (HEHE) is a soft tissue vascular tumor with an intermediate clinical course between benign hemangioma and malignant angiosarcoma. Due to its rarity and unpredictable behavior, it is difficult to standardize the treatment for the HEHE and a single therapeutic algorithm for all patients is not appropriate.

When a complete removal of the lesion is feasible, liver resection is the best treatment option, but palliative or incomplete resection is discouraged as aggressive tumor recurrence has been reported, probably due to the effects of resection-stimulated hepatotropic growth factor release on the neoplastic cells [48].

According the literature review of Mehrabi et al. [48] on 434 HEHE, the most common management was OLT (44.8 %) followed by no treatment (24.8 %), chemotherapy or radiotherapy (21 %), and liver resection (9.4 %). The 1-year and 5-year patient survival rates were 100 and 75 %, after liver resection; 96 and 54.5 % after OLT; 73.3 and 30 %, respectively, after chemotherapy or radiotherapy; and 39.3 and 4.5 %, respectively, after no treatment.

For the patients with extensive multifocal, bilobar disease, or anatomically difficult lesions, OLT is the most common and preferred treatment with 5-year survival rates ranging from 64 % in the UNOS area to 82 % in ELTR [49, 50].

Grotz et al. [51] reported the Mayo Clinic experience based on 30 patients with HEHE. OLT is a more appropriate treatment for diffuse disease pattern with more than ten nodules, more than four segments involved, and lesion size above 10 cm with 64 % of overall 5-year survival after OLT.

The post-OLT course is complicated by recurrence in approximately 30 % of the cases. In the study on 59 HEHE from ELTR, 96 % of the lesions were bilobar, and in 86 % of the cases, more than 15 lesions were detected in the liver specimen. Portal and/or hepatic vein thromboses were diagnosed in almost 50 % of the patients, and three patients presented an extrahepatic localization (2 pulmonary and 1 peritoneal) at the moment of OLT: 1 was treated with post-OLT lung resection and 1 with lung transplant, and the peritoneal lesion was resected during OLT followed by adjuvant chemotherapy.

At 3 months after OLT, two patients died for de novo lung lesion (21 and 70 months, respectively). The 23.7 % of the patients developed recurrent disease after a median time of 49 months, and the 15.3 % died of recurrent disease [50].

The mechanism of recurrence in the allograft is unclear: vascular invasion or extrahepatic disease demonstrated inconsistent influence on the clinical outcome after OLT. Lymph node invasion as well as limited extrahepatic invasion does not have to be considered a real contraindication for OLT: stability and regression of some extrahepatic metastases have been described. From the available data, only the macrovascular invasion affects the long-term outcomes [52].

Despite this good long-term survival, the incidence of HEHE recurrence rate, in and outside the graft, remains high, and currently, there is no consensus regarding the management of this recurrence. Efficacy of anti-VEGF [53] adjuvant therapies as well as other treatment modalities, including re-OLT, surgical resection, chemotherapy, chemoembolization, and radiotherapy, still remains debated due to the rare incidence of HEHE, which prevents large studies for reliable conclusions [51–56].

In conclusion despite satisfactory long-term results with 5-year survival close to 71 % and 5-year disease-free survival over 65 %, the role of OLT for HEHE is still debated and questioned on the basis of the high percentage of extrahepatic disease at the diagnosis, the risk of recurrence, and reports of long-term survival in non-treated patients.

OLT should be proposed at an earlier stage. The adjuvant therapy with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents has been advocated to decrease the risk of recurrence [53].

18.3.1 Liver Cell Adenoma and Liver Cell Adenomatosis

Liver cell adenoma (LCA) is a rare benign tumor of the liver often diagnosed, in asymptomatic patients, as an incidental finding during radiological procedures. The etiopathogenesis of LCA has not been fully clarified, although the relationship between the consumption of oral contraception or anabolic steroids containing androgens and the formation of LCA is obvious and dose dependent [57].

LCA is more frequent in patients with glycogenosis type Ia [58], III, and VI (with a greater risk of the cancer degeneration), tyrosinemias, galactosemia, b-thalassemias, steatohepatitis, hemochromatosis, familial polyposis, and Fanconi because of the use of androgens as treatment [59].

LCA has been recently classified into four different groups based on a combination of genetic aberrations and histological appearance [60, 61]:

1.

Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1-alpha inactivation with phenotypic features of marked steatosis, lack of cytological atypia, and absence of inflammatory infiltrates (40–45 %)

2.

β-catenin activation with atypical features such as pseudoglandular formation (15–19 %)

3.

Inflammatory group with presence of acute inflammatory infiltrate (30–35 %)

4.

Non-mutated HNF1α and β-catenin (unclassified) group without inflammatory infiltrate

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree