1. Identify those with active cardiac conditions/comorbidities suggestive of high risk and take steps to correct these conditions prior to elective surgery. They include:

Stable or unstable angina

Decompensated heart failure

Recent MI (within 6 months)

Decompensated heart failure

Significant arrhythmia

Severe valvular disease (specifically aortic or mitral stenosis)

2. Determine the severity of the surgery (inherent risk of the procedure)

Low risk (<1 %)

Endoscopic

Superficial

Intermediate risk (1–5 %)

Peritoneal

Thoracic

Orthopedic

High risk (>5 %)

Major vascular

Cytoreduction and HIPEC

Select pelvic cases

3. For those undergoing intermediate- or high-risk surgery, proceed with assessment of their functional capacity:

Assessment of metabolic equivalents (METs): based on treadmill test or patients ability to ambulate 4 blocks or two flights of stairs without symptoms.

(a) >4 METs = those with adequate functional capacity as seen on treadmill or asymptomatic may proceed with surgery

(b) For all others requiring further work-up (< 4METs): see Chap. 2 on perioperative risk assessment

Thromboembolic Disease: Obesity is also an independent risk factor for increasing the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) in patients undergoing abdominal surgery [12]. Many colorectal disorders such as cancer and inflammatory bowel disease also increase the risk of thromboembolic disease and are independent risk factors that are additive to an obese patient’s risk of having a thromboembolic complications with colorectal surgery. Therefore, preoperative administration of subcutaneous heparin with the use of sequential stockings as per SCIP and ASCRS guidelines is highly recommended [13]. Care must be taken to ensure appropriate timing of the heparin and also of the adequate dose. Obese patients may require a higher dose of unfractionated heparin, depending on their weight. A Cochrane review comparing various strategies for preventing DVTs in colorectal surgery demonstrated no difference in outcomes when low molecular weight heparin was compared to unfractionated heparin; however, the addition of compression stockings to heparin appeared to provide greater protection from DVTs [14]. Currently, we recommend pneumatic compression stockings with an appropriate dose of unfractionated heparin preoperatively, during the hospital stay, and in some patients (i.e., prior DVT or excessive BMI), postoperatively for up to 30 days. Postoperative prophylaxis after discharge is controversial, but several large reviews have demonstrated a significant reduction in the incidence of DVTs and PE in those treated after discharge [15, 16].

Diabetes: Diabetes is an independent risk factor predicting postoperative morbidity [17]. While hemoglobin A1c levels provide a global assessment of a patient’s overall glucose control, as it provides an indicator of the extent of hyperglycemia that has occurred during the life of a red blood cell (120 days), the perioperative stress may make even borderline insulin-resistant patients problematic to control. To facilitate adequate glucose control on the day of surgery, diabetic patients should be scheduled in the morning and the use half of their daily dose of insulin that morning. The patient also requires intraoperative monitoring and in some cases constant glucose monitoring with initiation of an insulin drip is required. Inadequate intraoperative glucose control (even in nondiabetics) has been shown to be associated with increased wound infections, operative re-interventions, and death [18]. However, correction of this proper insulin therapy lowers this risk to that of patients with normal blood glucose and is an important quality metric.

Laparoscopic Colectomy in the Obese Patient

Key concept: Even the straightforward laparoscopic cases in the obese patient present technical challenges that you need to prepare for and well versed with the technical nuisances to overcome them.

Laparoscopic colectomy offers improved postoperative outcomes compared to open in essentially every patient population, and this in no different in the obese patient. However, application of this technique in an obese patient clearly should be considered one of the most technically challenging laparoscopic operations, even for experienced surgeons. There are numerous reasons why this is difficult. Increased adipose of the retroperitoneum, mesentery, and omentum reduces peritoneal space and diminishes the “doming effect” of pneumoperitoneum, thus compromising video-scopic perspective. Additionally, mesenteric fat increases the volume of small bowel and mesentery to be retracted for exposure, while the overall thickness of the mesentery and its foreshortening makes vessel identification and division challenging. The omentum also poses a specific challenge for retraction due to its greater volume, weight, and adhesions. Unfortunately, the instrumentation that we use often adds to the complexity. The long thin miniature shaft and narrow end effectors used for grasping and dissection prove mechanically disadvantaged when attempting to manipulate the increased volume and weight of organs involved. Lastly, the use of gravity as the additional retractor in laparoscopic surgery poses significant issues in the morbidly obese. In order to adequately expose the operative field, extremes of body positioning with steep Trendelenburg and “reverse T” along with lateral tilt are needed. In reality, some of these are nearly impossible with the extremes of weight and poses hazards to peripheral nerves and even dislodgement of the patient (Fig. 26.1). Not surprisingly, the initial reports of laparoscopic colectomy often cited severe obesity as a relative contraindication to this technique.

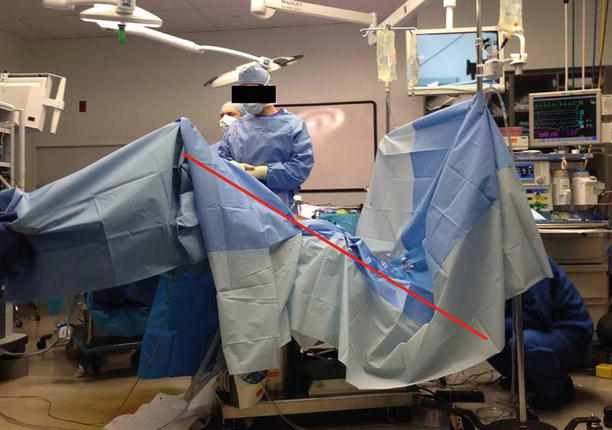

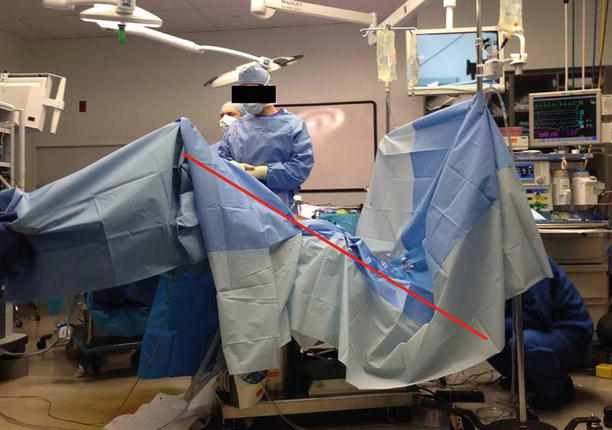

Fig. 26.1

Positioning a patient with massive obesity (BMI 80) for laparoscopic surgery (Courtesy of Justin A. Maykel, MD)

As in any other operation, preparation for a laparoscopic colectomy in the obese patient remains paramount. First, you must mentally prepare and comprehend that these cases possess unique challenges that increase in complexity as BMI increases. Also, you must be realistic by considering your own laparoscopic experience and where you are on the learning curve. Identifying a complex operation involves consideration of patient characteristics such as obesity, severity of pathologic condition, urgency, prior abdominal operations, and type of colectomy planned. Conversion serves as a surrogate marker for the degree of technical difficulty of a procedure but also may be a marker for good judgment on your part. In a study of nearly 1,000 laparoscopic colectomies, the authors identified surgeon experience, left-sided resection, fistula and abscess, and obesity as risk factors for conversion. Furthermore, there is an exponentially greater risk of conversion (vs. simply cumulative) when multiple factors are present. For example, an obese patient requiring sigmoidectomy for diverticulitis complicated by colovesical fistula will be a daunting task for any surgeon but especially for the surgeon with limited laparoscopic experience. This is not to say that you should not attempt a diagnostic laparoscopy, proceed with initial dissection, and perform the operation laparoscopically to the extent you feel safe and comfortable. This is often a great objective, at any point along your learning curve. One effective strategy is to set a time limit and determine ahead of time that if you are not making progress by the end that you will convert. Another operative approach in the patient described above or other complicated left-sided resections is to focus on the splenic flexure and colon mobilization. After that is performed, the fistula and resection can be approached through a low midline or Pfannenstiel incision under direct vision. Remember, a splenic flexure takedown in a morbidly obese patient with a heavy, thick body wall that has to be retracted in the open setting is not easy either.

Lesion Localization

Key concept: Have a plan and backup plan in place with obese patients to ensure the proper identification of the pathology and corresponding boundaries of resection.

As highlighted above, scheduling the case early in the day, budgeting appropriate operative time, and ensuring you have adequate surgical assistance and technical support will reduce the burden of these complex cases. A clear operative plan must also be in order. It may seem intuitive, but the first specific task is the proper identification of the colonic pathology requiring resection. You have likely already heard the basics—check your CT, review the scope report, and tattoo the site of the pathology. However, in the obese patient it is not always that simple. Identifying a serosal tattoo can be a challenge, as a large omentum, enlarged appendices epiploica, and abundant retroperitoneal and mesenteric fat often obscure the mark. By now you recognize that any lesion described as being in the region of the hepatic flexure and proximal to the rectum should be expected to be particularly concerning in this regard. To preoperatively localize the lesion for operative planning, we place an endoscopic clip (Fig. 26.2) at the lesion as a backup plan (especially in obese patients) and perform plain radiography for segment localization. Alternatively, the metallic clip can be identified on CT. Admittedly, overlapping segments of colon, especially with a floppy transverse colon, could occur on plain radiography, although this has yet to have occurred in our experience. One helpful tip is that if the KUB is performed immediately after colonoscopy, the residual gas in the bowel provides a well-delineated outline of distinct bowel segments effectively and easier identification of the metallic clip. This enables you to go to the operating room with confidence in a clear operative plan.

Fig. 26.2

Endoscopic photo of metal clip, useful to radiologically localize the polyp or tumor

This simple maneuver may allow you to position the patient supine for a right colectomy and avoid lithotomy positioning and the potential risks of DVT and peripheral nerve injury. Remember, positioning is a major component of operating on the morbidly obese, something we will address shortly. If nothing else, you can avoid searching for the tattoo prior to initiating dissection and mobilization, potentially reducing operative time. This is not to say we avoid a tattoo. Rather, the clip serves as a backup, and tattoo identification provides the ultimate intraoperative confirmation; therefore, we still find the tattoo of benefit. This also obviates the need for on-table colonoscopy to localize the lesion—another often discussed, but in practice, time-consuming and more difficult maneuver.

We routinely ask our institution’s gastroenterologists to perform both a three-quadrant tattoo and endoscopic clip for lesions in the vicinity of the transverse colon, either flexure, or the descending colon. The difference in difficulty of a splenic flexure resection as opposed to sigmoid colectomy cannot be overstated in normal-sized patients. When you are dealing with the morbidly obese, this becomes magnified. Mid- or distal transverse colon lesions may be approached as an extended right colectomy versus variations of a left colectomy. Descending colon lesions pose similar challenges in terms of the extent of resection. Should you perform an extended left colectomy and potentially require consideration of transverse colon to rectal anastomosis? An ileal mesenteric window may be necessary to facilitate tension-free anastomosis, especially given the foreshortening of a thick mesentery in an obese patient. Another alternative to reach the pelvis with the mid-transverse colon is to fully mobilize the right colon and turn the right colon mesentery counterclockwise into the pelvis as a straight line. How often have you done that and what is the orientation of the right colon you are going use to bring down to avoid twisting or cutting off blood supply? These are often things we bring up on boards or in conference, but many of you may have never seen or tried these technical steps. The benefit of being able to think through this decision process prior to going to the operating room cannot be overstated. Thus, in the obese patient who already poses significant technical difficulties, being able to anticipate such operative decision-making prior to surgery enhances surgical performance.

The Value of Your Assistant

Key concept: Approaching your more complex cases in the obese patient with someone not facile in laparoscopic surgery, using the camera, or providing adequate exposure is a setup for failure from the beginning.

A standard laparoscopic resection in the obese patient will require a skilled surgical assistance. If you are at an institution with senior surgical residents or colorectal/minimally invasive fellows available, such an issue may not be germane. However, in a private institution, another attending or highly experienced surgical assistant should be present. Certainly, the feasibility of laparoscopic colectomy in the obese patient has been demonstrated. Delaney and colleagues compared laparoscopic colectomy in an obese cohort compared to a matched control group and found a similar length of stay and no increase in overall complications. However, not unexpectedly, they did show an increased operative time and higher conversion to open rate in the obese cohort [19]. Leroy and associates also reported on laparoscopic sigmoid colectomy in the obese patient where they described their consecutive series of 29 patients without conversion [20]. Utilizing a 5- or 6-port technique with excellent results, however, more pointedly illustrates the need for a team approach, with multiple skilled assistants, to achieve technical proficiency.

Patient Setup, Port Placement, and Exposure

Key concept: Your setup is the initial key to your success in the OR. While you may still struggle, problems at this stage will almost assuredly make things much more difficult.

By now you realize that the extremes of rotation allow you to maximize gravity’s effect for providing exposure in laparoscopic colectomy (Fig. 26.3). This is much more difficult in the morbidly obese patient. The first step you need to focus on is properly positioning, padding, and securing the patient to the operating room table. Depending on your table, once your patient’s weight approaches over 400 lb, you must ensure that the table meets the requirements for supporting them. To secure the patient, there are several systems available and different surgeons have their own preferences; yet all focus on avoiding slipping and causing any traction or pressure-related injury. We prefer to use 3-in. wide silk tape over a barrier towel across the patient’s chest wrapped three times around the table. Others describe using beanbags, foam securing systems, IV bags at the shoulders (not recommended), arm sleds, and gel pads on the operating room table. Some even secure the bed sheet to the lowered foot of the bed. While it is important for you to find what works for you, consider this word of caution if you are a beanbag user. Because we rely on a fulcrum of downward movement of your graspers to raise the colon (especially with a medial approach), having your beanbag inflated high up on the patient’s side will cause you to hit the beanbag and lose this ability. Curling it slightly back or avoiding this tight “high-riding cocoon” will avoid this common mistake. We also recommend a “dry run” before prepping and draping by having anesthesia put the patient in all 4 extremes of position and ensuring the patient is adequately secured. That way, everyone in the operating room can see the patient does not fall and provides confidence during the case when the drapes are on and the operating room is dark and you ask for steeper positioning.

Fig. 26.3

OR positioning for laparoscopic colectomy showing steep Trendelenburg, a maneuver that helps with retraction and exposure. Red line indicates the patient’s orientation in steep Trendelenberg

We recommend insertion of ureteral stents for patients with prior pelvic surgery, radiation, and other situations where ureteral anatomy may be altered. We also find stents helpful when fistulizing disease is present—either to the bladder or the vagina—or if large abscesses or phlegmons (either retroperitoneal or pelvic) complicate the intestinal disease. In our opinion, obesity in and of itself is not an indication for ureteral stent insertion. Identification of the ureter in a very large patient with excessive mesenteric and retroperitoneal fat can be daunting and cause a lot of heartache and prolonged operating room time. Stents may be one means by which critical steps of the operation can be facilitated.

We recommend using more ports than you are normally accustomed for additional graspers to provide retraction and aid in the dissection. Have them available ahead of time. Since these are “bariatric patients,” you need to have bariatric length equipment—cameras, graspers, and staplers. Traditional ports that you are accustomed to using may not adequately reach through the body wall and longer trocars may be required. Regarding port placement, the principles of maximizing exposure to all parts of the abdomen by maintaining good ergonomics and triangulation still apply in the obese individual. Again, as you need to elevate the heavy colon and bulky mesentery, moving your ports a little more medially than normal will allow you to maintain the optimal fulcrum. When the ports are placed too lateral, you will often hit the bed with your grasper and not be able to manipulate the instruments freely. Remember, this is further exacerbated by the lack of working space in between the bowel and anterior abdominal wall with a standard pneumoperitoneum at 15 mmHg.

Exposure to the central mesentery is difficult as a result of bulky visceral fat. A medial-to-lateral approach may thus be difficult, or even not possible. Therefore, you should be skilled and prepared to employ the spectrum of colonic mobilization techniques: lateral to medial, superior or “top-down” starting at the transverse colon, and inferior to superior. Be flexible and be willing to switch to a different approach during the various steps of the operation to accommodate the patient’s habitus and pathologic condition. In addition to placing additional ports, one way to handle the bulky omentum is to take down the falciform ligament. This will provide a broad space over the top of the liver and the anterior stomach to flip the omentum back up on itself. A small sponge pad placed through a 10 mm trocar or hand port can “stick” to the omentum and anterior abdominal wall, retracting the omentum away from the operative field. Opening the sponge (or rolling it) and using it as a barrier to hold back the creeping small bowel is often helpful as well.

Dissection Techniques

Key concept: Gaining access to the correct plane and using precise sharp dissection will be helpful. Take care of all bleeding early as even small amounts will distort tissue planes and make dissection more problematic.

Standard dissection and identifying the correct planes is similar regardless of body habitus—it is the degree of difficulty that varies. In general, I (HDV) favor energy devices for mobilizing the bowel and, in particular, find ultrasonic dissectors to have finer tips that facilitate sharp dissection. The key, ultimately, is to ensure adequate hemostasis. Tissue planes are distorted and the visual effect of “yellow out” (similar to “white out” during a snow storm) can lead to imprecise dissection, violating embryologic planes, and lead to small (or large) amounts of meddlesome bleeding. Avoid grasping on the fatty mesentery and attempting to elevate its bulk—it will likely tear and bleed. Atraumatic graspers on the bowel or epiploica utilizing a larger bite (i.e., similar to grasping a vein), while avoiding tearing, will avoid serosal or even full-thickness bowel injuries. Increased blood loss—another surrogate marker for technical difficulty—may not be measurably different, but it is our impression that obese patients have greater bleeding during mobilization and blood staining of tissues can further obfuscate dissection planes. Furthermore, due to differences in hemoglobin-related light absorption, this will result in decreased laparoscopic illumination and visualization.

The extent of mobilization should be considered. You should anticipate mesenteric shortening and the resulting possibility of encountering increased tension at your intended anastomosis site. This mandates a disciplined attention to ensuring complete mobilization of the colon to avoid this scenario. We have found several keys to help in this aspect. First, mobilize back to the root of the mesentery—while this is often a bit worrisome for the novice surgeon in a heavy patient with thick mesentery and ill-defined planes, it is needed to gain length. Next, completely mobilize the mesentery cranially and caudally, and always mobilize the flexures. Many surgeons selectively take down the flexures—in obese patients, this is the norm. The omentum can either be dissected off the colon or taken with specimen, the lesser sac needs to be entered, and you have to divide the retroperitoneal attachments to ensure a full flexure mobilization. Additionally, vessels are divided high to achieve full mobilization and to avoid ischemia at the distal end of the bowel. This proximal division reduces the number of vessels and volume of tissue to be divided, but requires precise, disciplined dissection with skeletonization of the named vessels to ensure adequate primary and collateral vascularization. I (HDV) prefer staplers for vessel division, due to the volume of tissue divided, though many surgeons successfully used energy devices alone. All these maneuvers typically provide enough mobility to the remaining bowel to effect a tension-free anastomosis. This is also crucial when bringing up a colostomy. Without adequate mobilization and preservation of blood supply, your patient may be left with a sunken or stenotic stoma (Fig. 26.4), an extremely difficult problem to deal with in this population.