16

The management of achalasia and other motility disorders of the oesophagus

Introduction

For many years oesophageal manometry was done using water-perfused systems that were difficult to set up and with many technical constraints. These were gradually replaced by solid-state pressure transducers.With further miniaturisation and developments in computer software, thin catheters containing multiple pressure recording transducers (high-resolution manometry) have become widely available, leading to novel ways of displaying pressure information as isobaric contour plots using colour gradations to indicate different pressures (high-resolution oesophageal pressure topography). The latter systems have disclosed considerable new information about oesophageal motor disturbances, resulting in new criteria (Chicago classification, Table 16.1) to define these disorders.1 Further details of manometry techniques are described in Chapter 12 and manometry of a normal swallow is shown in Fig. 12.1.

Table 16.1

The Chicago classification of oesophageal motility

| Diagnosis | Criteria |

| Achalasia type I | Classic achalasia: mean IRP > upper limit of normal, 100% failed peristalsis |

| Achalasia type II | Achalasia with oesophageal compression: mean IRP > upper limit of normal, no normal peristalsis, pan-oesophageal pressurisation with ≥ 20% of swallows |

| Achalasia type III | Mean IRP > upper limit of normal, no normal peristalsis, preserved fragments of distal peristalsis or premature (spastic) contractions with ≥ 20% of swallows |

| Oesophagogastric junction outflow obstruction | Mean IRP > upper limit of normal, some instances of intact peristalsis or weak peristalsis with small breaks such that the criteria for achalasia are not met |

| Distal oesophageal spasm | Normal mean IRP, ≥ 20% premature contractions |

| Hypercontractile oesophagus | At least one swallow DCI > 8000 mmHg • s • cm with single peaked or multipeaked contraction |

| Absent peristalsis | Normal mean IRP, 100% of swallows with failed peristalsis |

| Weak peristalsis with large peristaltic defects | Mean IRP < 15 mmHg and > 20% swallows with large breaks in the 20 mmHg isobaric contour (> 5 cm in length) |

| Weak peristalsis with small peristaltic defects | Mean IRP < 15 mmHg and > 30% swallows with small breaks in the 20 mmHg isobaric contour (2–5 cm in length) |

| Frequent failed peristalsis | > 30%, but < 100% of swallows with failed peristalsis |

| Rapid contractions with normal | Rapid contraction with ≥ 20% of swallows, DL > 4.5 s |

| Hypertensive peristalsis (nutcracker oesophagus) | Mean DCI > 5000 mmHg • s • cm, but not meeting criteria for hypercontractile oesophagus |

DCI, distal contractile integral; DL, distal latency; IRP, integrated relaxation pressure.

Achalasia

The term ‘achalasia’ comes from Greek, meaning ‘failure to relax’. It was first used by Sir Arthur Hurst early in the 20th century, although the clinical features were first described in 1697 by Thomas Willis. It is conventionally defined by the absence of peristalsis (this does not mean the absence of contractions) in association with a lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) that fails to relax completely. High-resolution pressure topography recognises this classic type (type I) but also considers two other types of achalasia, where there can be either pan-oesophageal pressurisation to more than 30 mmHg with at least 20% of swallows (type II) or preserved fragments of distal peristaltic activity or premature (spastic) contractions with at least 20% of swallows (type III).2 These last two types probably represent the entity usually referrred to as ‘vigorous achalasia’ when seen on conventional manometry. Primary or idiopathic achalasia needs to be considered separately from secondary achalasia. While symptoms may be similar, the presence of a specific aetiology can influence management. These secondary causes are discussed later in this chapter.

Primary achalasia

This is an uncommon condition with an incidence in the Western world that is probably less than 1 case per 100 000 people per year.3 It is due to progressive loss of ganglion cells in the myenteric plexus of unknown cause. The neural loss is somewhat selective as there is particularly severe loss of inhibitory nitrergic neurotransmission.4,5 This process is often accompanied by an inflammatory infiltrate that has led to many theories regarding aetiology. While there is circumstantial evidence of viral exposure and autoimmune phenomena, neither provides a satisfactory explanation for all patients.5

Investigations

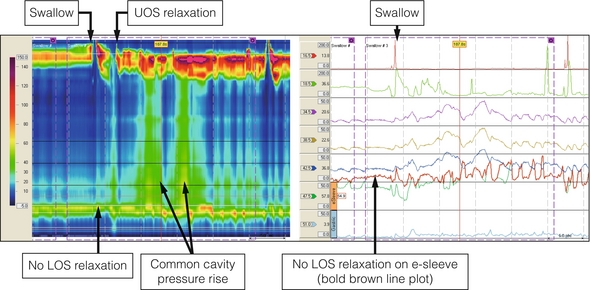

A firm diagnosis can only be made by oesophageal manometry. High-resolution techniques suggest that conventional manometry, however, only diagnoses about a quarter of patients with achalasia on the basis of the classic features of a hypertensive lower oesophageal sphincter that does not relax completely on swallowing, aperistalsis of the oesophageal body and a raised resting pressure in the oesophagus (Fig. 16.1). The other two variants can be separated by the Chicago classification and this may be clinically relevant. Limited evidence suggests that patients with type II achalasia with pan-oesophageal pressurisation do respond well to treatment, but this seems not to be the case for type III.2

Figure 16.1 Achalasia. High-resolution manometry from a patient presenting with dysphagia and regurgitation. The swallow is followed by a ‘common cavity’ rise in oesophageal pressure indicating filling. LOS relaxation is absent and there is a positive oesophagogastric pressure gradient. Upper oesophageal sphincter (UOS) relaxation shortly after the swallow was related to regurgitation of oesophageal contents.

Treatment

Botulinum toxin injection

This involves the injection of 100 units of botulinum toxin into the LOS.

When compared to pneumatic dilatation in a randomised trial, only 32% of patients who had received botulinum toxin were in symptomatic remission after a year compared to 70% after dilatation.7 A Cochrane review published in 2006 came to the conclusion that botulinum toxin injection was inferior to pneumatic dilatation at 6 months.10

Pneumatic dilatation

There is wide variation in the incidence of GORD (between 4% and 40%) after successful dilatation, which reflects method of assessment (symptomatic versus endoscopic), the number of repeat dilatations and the length of follow-up.13–15 In most patients, however, this can usually be controlled satisfactorily with a proton-pump inhibitor.