DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF THE GERIATRIC POPULATION WITH END-STAGE KIDNEY DISEASE

Incidence and Prevalence of End-Stage Kidney Disease in the Elderly

When the Medicare end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) program was funded in 1973, individuals receiving dialysis comprised the healthiest, most motivated, and youngest segment of the population with kidney failure. The advent of systematic funding of ESKD care in the United States widened the availability of renal replacement therapies and rendered committees judging “Who Shall Live and Who Shall Die” obsolete. Renal replacement therapies have now become available to all segments of the population, including the elderly (15).

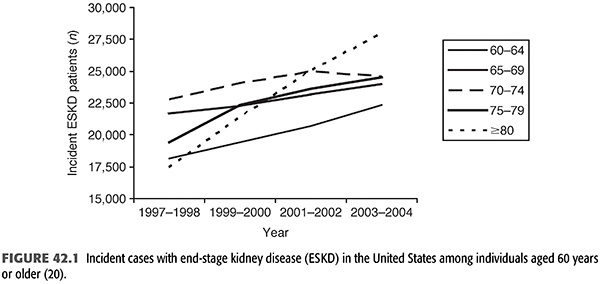

Patients older than 65 years represent a rapidly growing segment of the population with ESKD in North America, Europe, Australia, and Japan (10,16–19). This is particularly notable among octogenarians and nonagenarians (FIGURE 42.1). In the United States, from 1995 to 2004, there was a greater than 60% increase in incident dialysis patients 80 years and older, such that in 2004, approximately 28,000 individuals in this age-group initiated dialysis (21). In more recent years, incident cases of ESKD in those aged 75 years and older appear to have plateaued, but the incidence rate remains highest in this age-group (21). However, these oldest old comprise a fraction of the elderly hemodialysis (HD) population; in 2011 to 2012, there were 56,000 incident patients with ESKD 65 years or older, representing 50% of the incident U.S. dialysis population.

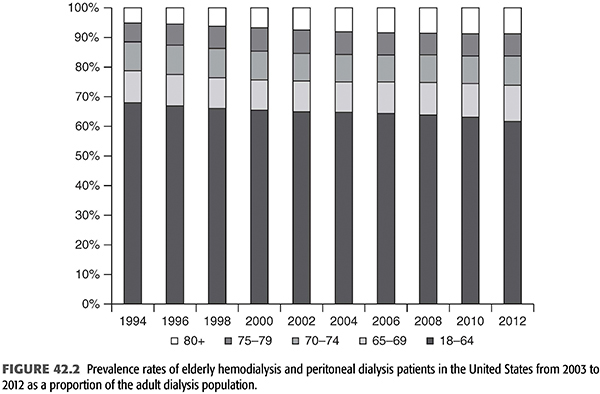

Despite higher mortality rates and lower life expectancy, the rise in the elderly dialysis population in the United States is seen in prevalent as well as incident HD patients. In 2012, there were 244,324 individuals age 65 years and older prevalent in the ESKD program compared with 166,695 patients in 2004. This comprises 38% of prevalent patients with ESKD (includes individuals with a functioning transplant) and 44% of prevalent dialysis patients. The very elderly (over age 75 years) on dialysis numbered more than 94,000 (21% of the dialysis population). Although the rise in the total number of dialysis patients in the United States is apparent in all age-groups, with the prevalent dialysis population increasing from 335,000 in 2004 to 450,000 in 2012, the largest proportional increase (50%) is seen among individuals 75 years and older (FIGURE 42.2) (20).

As with younger patients, there remains a disproportionate, albeit far less marked, overrepresentation of ethnic minorities in the elderly U.S. population with ESKD. Although African Americans comprise 35.5% of the incident population with ESKD younger than 65 years, they comprise only 22.8% of the population with ESKD 65 years and older and just 17.3% of octogenarians and nonagenarians. A similar pattern is seen for those of Hispanic ethnicity (both African American and non–African American Hispanics), where the proportion of incident Hispanic dialysis patients declines as the population ages from more than 17% in individuals younger than 65 years to 11% among individuals aged 70 to 75 years and fewer than 9% among those 80 years and older (20). The reasons for this demographic shift are not known.

Causes of End-Stage Kidney Disease in the Elderly

Similar to the population as a whole, the most common causes of ESKD in the elderly are diabetes and hypertension. Among individuals 50 to 69 years old, diabetes is the primary cause in 50% and hypertension in 23%. In contrast, hypertension is reported as the primary cause in 38% of incident dialysis patients 70 years and older and in 46% of patients 80 years and older (FIGURE 42.3). This pattern is similar for prevalent dialysis patients (FIGURE 42.3). Notably, diabetes is increasingly the primary cause of incident ESKD in individuals both older and younger than 70 years (20). Unfortunately, due to the reluctance to biopsy elderly patients, even in the presence of common indications for biopsy including nephrotic-range proteinuria and unexplained kidney failure, elderly patients with treatable causes of kidney failure may go underdiagnosed and therefore untreated (17,22–24). This may explain the high prevalence of hypertension as the primary cause of kidney failure as this diagnosis is often indicated in the absence of other known causes. Critically, elderly patients with atypical presentations of ESKD should be evaluated for treatable causes of kidney disease just as younger patients are.

Mortality in End-Stage Kidney Disease in the Elderly

Although mortality is higher in the elderly ESKD population compared to their younger counterparts, elderly individuals with ESKD do surprisingly well on dialysis. In 2003, median survival was 16 months for individuals aged 80 to 84 years but dropped to less than a year for those 85 years and older. This compared with median survival of 24 months among individuals aged 65 to 79 years initiating dialysis in the United States (25). More recent data from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) demonstrates a median survival of 3 years for those patients starting dialysis after age 75 years compared to 6 years for those aged 45 to 74 years old (26).

This pattern is similar in other countries, and, with careful management, many elderly dialysis patients accommodate well to ESKD and maintain reasonably good quality of life (27–30). In Italy, patients initiating dialysis at age 65 years or older (mean 71.3 years) had a survival rate of 82.7% at 1 year and 62.3% at 2 years (31). In Spain, dialysis patients aged 65 to 85 years had the same mortality rate as the age-matched general population (32). A German study of 76 patients starting dialysis after age 80 years reported 1-year survival of 87% and 3-year survival of 52%. They noted improved outcomes linked with duration of predialysis nephrology care (33). In the very elderly dialysis population in Japan, the median survival in those 80 to 84 years old, 85 to 89 years old, and >90 years old was 3 years, 2.5 years, and 0.9 years, respectively (19). In a retrospective analysis from the United Kingdom, patients starting dialysis after age 80 years had 1-year survival of 78.5%, whereas the median time to death for those who pursued maximum conservative therapy for their advanced kidney disease was 6 months. However, these results may have been skewed by some selection bias (34). Röhrich et al. (35) note that in their practice, there has been a progressive increase in mean survival time for patients who begin treatment when older than 80 years, from 22.7 months before 1990 to 28.3 months after 1990; they opine that this is due to improvements in dialysis techniques, diet, and anemia therapy. Despite these outcomes, a survey of physicians in the United Kingdom conducted in 1996 showed that a previously healthy octogenarian would not be referred for dialysis by 68% of primary care physicians or accepted for dialysis by 28% of nephrologists (36). Given the growth in the elderly dialysis population, it appears that these practices are changing.

Dialysis Modality

Elderly individuals initiating dialysis in the United States overwhelmingly receive HD. Compared to incident patients with ESKD younger than 65 years where 82.8%, 10.0%, and 3.8% initiated renal replacement therapy with HD, peritoneal dialysis (PD), and transplant, respectively, patients with ESKD 65 years and older had rates of 89.8%, 5.8%, and 0.9%, respectively, in 2012. This trend is most marked in the oldest patients with ESKD, where only 4.8% initiated renal replacement therapy with PD (21).

INDICATIONS FOR INITIATION OF DIALYSIS

INDICATIONS FOR INITIATION OF DIALYSIS

Chronic Dialysis

The decision to initiate dialysis in the elderly is multifaceted, requiring careful weighing of advantages and disadvantages associated with this lifesaving modality. Unfortunately, many patients are not referred to nephrologists with sufficient time for careful decision making for initiating dialysis or determination of the optimal modality should the patient decide to initiate dialysis therapy. Non-nephrologist physicians may not be aware that elderly patients are candidates for dialysis therapy and may not recognize the severity of their kidney dysfunction, potentially leading to late referral. After adjusting for comorbid conditions, Mignon et al. (37) found that the increased mortality observed in the elderly in the first 3 months of dialysis correlated with late referral. It has been questioned whether earlier initiation of dialysis in the elderly may reduce this excess early mortality, but studies have not been conclusive. Meta-analyses certainly do not support the idea of initiating HD at a higher glomerular filtration rate (GFR), but there may be benefit to starting peritoneal dialysis earlier (24,38,39).

Determining when to initiate dialysis in elderly patients can be challenging due to problems of assessing kidney function in this population and the overlapping symptoms of uremia with other chronic or acute conditions common in the elderly. Decreased protein intake and loss of muscle mass lead to maintenance of the serum creatinine values despite an approximately 10% decrease in GFR per decade after the age of 40 years (40). Estimating equations, such as the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equation, are developed to accommodate this age-related change in creatinine generation (41,42). Although used widely, the MDRD equation tends to overestimate GFR in the elderly and recently has been shown to be less accurate than the newer Chronic Kidney Disease-Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-epi) and Berlin Initiative Study (BIS) equations (43). In addition, GFR-estimating equations cannot account for accelerated muscle loss that may occur with very frail or sick patients and therefore tend to overestimate actual GFR in such patients. Cystatin C, a filtration marker that is not generated from muscle, has been posited to be a better marker than creatinine, especially in the elderly. However, we now know that there are non-GFR determinants of cystatin C levels, making its utility as a sole filtration marker similar to that of serum creatinine. The most accurate GFR estimation equations in the elderly appear to be those that include both serum cystatin C and creatinine measurements (43).

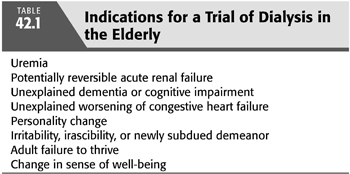

In addition, symptoms often attributed to uremia are commonly seen in other chronic conditions in the elderly. Porush and Faubert (16) evaluated the signs and symptoms present before initiation of maintenance dialysis in 118 elderly patients. The most common symptoms were anorexia and weight loss (61%), generalized weakness (58%), encephalopathy (49%), and nausea and vomiting (41%), many of which are seen in other diseases. Some potential indications for a trial of dialysis in the elderly are listed in TABLE 42.1. There are several reasons why nephrologists may not initiate dialysis in an elderly person. In particular, it may be appropriate not to initiate dialysis in patients with dementia given the need for cooperation to safely deliver adequate dialysis.

Acute Dialysis

The effect of age as an independent risk factor for development, mortality, and prognosis in acute kidney injury (AKI) has been well established (44–51). In a study of critically ill patients, there was a 20% greater rate of AKI in those patients greater than 75 years compared with the age-group of 18 to 54 years (52). An analysis of Medicare data showed that for the years 1992 to 2001, the overall incidence rate of AKI was 23.8 cases per 1,000 discharges, with rates increasing by approximately 11% per year. Older age, male gender, and African American race were strongly associated (p <0.0001) with AKI (53). Subsequent data has demonstrated a further increase in incidence of AKI across all ages and races from 2000 to 2009 (52). As advanced age is a strong risk factor, this increase in AKI to some extent is explained by the overall growth in the elderly population (44,51). Other contributing factors include higher incidence of comorbidities such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease (CKD), in addition to exposures such as surgery, sepsis, and nephrotoxic medications (44,45,54).

In addition to age, prognosis in AKI appears related to the presence of comorbid conditions, cause of the acute illness, oliguria, requirement for dialysis, and number of nephrotoxic events (44,45,47,54–57). In the analysis of Medicare patients described earlier, the in-hospital mortality rates were 15% and 33% in discharges with AKI diagnostic codes as the principal and secondary diagnosis, respectively, compared to 5% without a diagnosis code for AKI. Death within 90 days of hospital admission was 35% and 49% in discharges with AKI as the principal and secondary diagnosis, respectively, compared to 13% in discharges without AKI (46). Among cases of AKI, mortality was greatest in the oldest patients (52,58). In critically ill patients with AKI, in-hospital mortality was 24% versus 13.9% when comparing the oldest patients (>75 years) to the youngest (<54 years). This trend continued to the 90-day point with mortality rates of 35.7% versus 17.2% in the oldest versus youngest groups (52). In terms of renal recovery, a meta-analysis of 17 studies demonstrated advancing age to be a negative predictor of renal recovery (59). Kane-Gill et al. (52) noted an overall renal recovery rate at 90 days of 31%, but patients aged 18 to 54 had a 15.8% higher rate of recovery compared with those over age 75 years.

There is frequently reluctance to initiate dialysis in an elderly individual with AKI and multiple medical or psychosocial disorders because of the fear of committing the patient to chronic long-term dialysis or because of ethical concerns (60). In fact, despite the highest incidence of AKI, patients over age 75 years are least likely to receive renal replacement therapy (RRT) (52). However, while elderly survivors of AKI seem to require more time for total recovery and recover function less completely, dialysis should not be automatically withheld. These patients should be involved in a shared decision-making process with the nephrologist and a trial of dialysis should be considered following a discussion of overall prognosis, comorbidities, functional status, and perceived risks and benefits of RRT (45,60–62).

CHOOSING A RENAL REPLACEMENT THERAPY MODALITY

CHOOSING A RENAL REPLACEMENT THERAPY MODALITY

Hemodialysis versus Peritoneal Dialysis

As in younger populations, factors affecting the selection modality for treatment of ESKD in the elderly include patient or physician preference, availability of trained personnel, proximity to a dialysis center, concurrent illnesses or comorbid conditions, and specific contraindications to a particular modality. Potential advantages of PD in the elderly include better preservation of renal function, avoidance of large volume or electrolyte shifts leading to improved cardiovascular stability, allowance of a more liberal diet, avoidance of vascular access, decreased transportation time, and ease of travel and holiday times (63). Patients who tolerate HD poorly because of cardiovascular disease or difficulty with vascular access also may do better with PD (64,65), whereas HD may be a better choice for patients with inguinal or abdominal hernias, diverticulitis, compromised peritoneal surface area secondary to abdominal surgery or adhesions, abdominal aortic aneurysm, morbid obesity, or physical or psychosocial inability to perform PD (9). Many patients find PD more compatible with an independent lifestyle and desire active participation in their treatment, whereas others find the responsibility of self-care overwhelming. There may be age bias in this selection process (66).

There are conflicting reports as to the survival advantage of one modality over another in elderly patients. In a small European study of patients older than 70 years, the annual mortality rates in PD versus HD were similar (26.1 vs. 26.4 deaths per 100 person-years) (67). However, other analyses in the United States have suggested increased mortality rates for those on PD, particularly among the elderly and those with diabetes (68–70). A study of 1,041 patients beginning HD and PD in 81 dialysis clinics in 19 U.S. states showed an increased risk for mortality for PD patients after the first year of dialysis with no difference based on patient age (71). Recent large cohort studies have provided more clarity on the issue. In an analysis of all incident dialysis patients between 1996 and 2004 in the United States, Mehrotra et al. (72) demonstrated no significant difference in risk of death between those treated with HD or PD in the cohort of patients beginning dialysis after 2002. The increased mortality that had previously been seen in PD patients decreased over time, suggesting that advances in PD have seemingly closed this survival gap between HD and PD. In concordance with prior studies however, the subset of diabetic patients over age 65 years continued to have an increased risk of death with PD (72). In a large study of all incident dialysis patients in the United States, Weinhandl et al. (73) used a propensity-matching scheme to compare HD versus PD survival given the inability to have a true randomized trial. Their results support the finding of decreased survival with PD versus HD in patients >65 years of age, diabetics, and those with cardiovascular disease (73). It has been suggested that poor nutritional status in diabetic PD patients may account for increased mortality (74). Excess mortality for elderly PD patients is relevant in consideration of appropriate treatment modality and must be included in the equation along with considerations of comorbidity, quality of life, distance from center, and other issues.

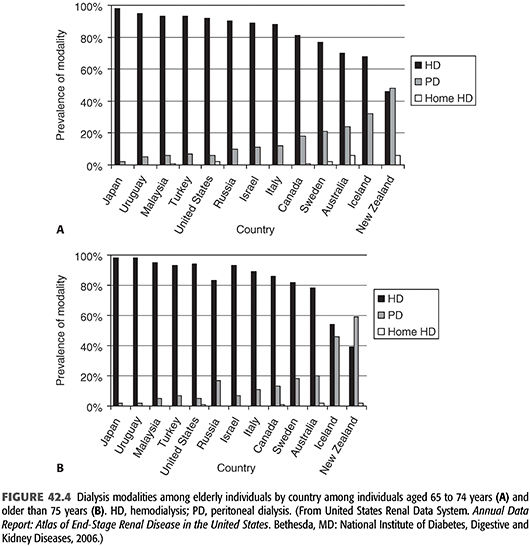

Peritoneal Dialysis in the Elderly

In the United States, 8.1%, 6.4%, 5.9%, and 4.9% of dialysis patients aged 20 to 44 years, 45 to 64 years, 65 to 74 years, and older than 75 years are on PD compared to 49.7%, 60.2%, 70.0%, and 86.1% on HD (20). Other countries have a higher use of PD, likely in part, due to geographic and financial considerations. In Hong Kong, Mexico, and New Zealand, for example, 74%, 49%, and 33% of patients are on PD, respectively (20). In most countries, PD use decreases as patients age, especially for the older-than-75-year age-group; exceptions are New Zealand and Iceland, where 60% and 47% of patients aged 75 years or older were treated with PD as of 2004 (75). Worldwide use of home HD also decreases dramatically with age; in-center HD is the predominant modality for dialysis patients older than 65 years (FIGURE 42.4) (75).

As a home-based modality, PD may help elderly patients with ESKD maintain independence (63). Additionally, in patients with excessive volume gains, hemodynamic instability, or limited vascular access options, PD may be the most desirable ESKD treatment modality for medical reasons. Unfortunately, many elderly patients may perceive limitations in their ability to perform PD; reasons include decreased strength and manual dexterity, vision problems, limitations in mobility, and anxiety. Another limitation, not often considered, is storage space for dialysate and potentially for a cycler; this may assume greater importance in the elderly who often have limited housing options. Finally, assistance from a family member or paramedical staff may be essential (76). Automated PD, such as continuous cyclic peritoneal dialysis (CCPD), or intermittent peritoneal dialysis (IPD) may be a good option for the elderly patient who requires assistance with dialysis, particularly when the assisting spouse or children work during the day (63,77–79).

A recent retrospective cohort study in France analyzed data from all incident PD patients between 2002 and 2010. In comparing those requiring assisted PD (PD performed with assistance of a health care technician, community nurse, or family member) versus self-care PD, they found a lower risk for transfer to HD (80). Those patients requiring assisted PD were generally older (mean age 78 years vs. 56 years), had a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index, and were found to have a higher risk of death attributed to the aforementioned differences between these groups. A cost analysis of this French system found PD, even when requiring assistance, a cheaper alternative to in-center HD (81). In Hong Kong, a comparison of elderly patients on assisted chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) and those performing self-care CAPD noted no difference in patient survival, technique survival, or peritonitis-free period between these groups. Two-year survival was 88% in the self-care group and 95% in the assisted group with technique survival rates of 84.7% and 80.9%, respectively (82). In a recent study in Toronto, Canada, when home care assistance was available, only 20% of the elderly population had contraindications to PD, and 59% of those eligible accepted it (83). These experiences suggest a role for assisted PD to safely and effectively increase utilization of PD among the elderly.

Home Hemodialysis in the Elderly

In recent years, there has been increased international interest in home HD as an alternative to both PD and in-center HD. Several nonrandomized studies have shown improved morbidity and mortality, although the magnitude of the advantages may differ on method of delivery (84–86). Home HD requires a high level of functional status and independence by the patient as well as appropriate physical space, support, and resources (84,86). Given the multiple comorbid conditions and common frail status, many elderly patients may not be eligible for this therapy.

In the United States in 2012, 0.4% of dialysis patients aged 65 to 74 years and 0.3% of patients aged 75 years and older chose home HD as their first modality; this is comparable to the very low level of home HD use in other age-groups in the United States (20). Worldwide, the proportion of individuals using home HD declines as the population ages (75,87). Agraharkar et al. (85) suggest that staff-assisted home HD may be an appropriate short-term option for debilitated or terminally ill patients, particularly when ambulance transportation is required. A financial analysis performed in 2002 revealed that staff-assisted home HD was less costly than either in-hospital HD or outpatient HD with ambulance transportation, with a week of staff-assisted home HD costing $1,200 and a week of in-center HD with ambulance transportation costing $2,640 (United States).

Transplant as a Modality for Kidney Replacement in the Elderly

Although low, transplant rates among the elderly have been steadily rising. In 1990, only 1.9% of all transplants in incident ESKD patients occurred in those over the age of 65 years, while in 2002, this number had increased to 7.7%. According to 2012 United States Renal Data System (USRDS) data, 16.6% of incident ESKD patients receiving transplants were between the ages of 65 and 74 years, and 2% were 75 years or older (20).

Recent reports have recognized the benefits of kidney transplantation for carefully selected older patients (88–90). Although elderly transplant recipients have a higher mortality rate than younger patients, they also have a 41% lower risk of death than age-matched patients on the transplant waiting list (89,90). In a 2005 study, the expected survival for dialysis patients over the age of 70 years was 8.2 years for those who received a kidney transplant compared to 4.5 years for those that remained on the wait-list (91). Wolfe et al. (89) showed that the risk of death decreases below the waiting list group by 148 days after transplant in the elderly as compared to 95 days for patients aged 40 to 59 years. Owing to reduced life expectancy in older adults, death with a functioning graft occurs in 50% of patients older than 65 years, and most grafts last throughout the life of the transplant patient (88,91,92).

Given the heterogeneous population of older patients with ESKD, it may be a challenge for medical providers to decide which patients to recommend for transplant evaluation. Decision to refer a patient for transplant evaluation should be made on an individual basis, independent of age (27,93–96). As in younger patients, kidney transplantation evaluation should be performed to identify conditions that may interfere with surgery, recovery, or the patient’s survival after surgery. Advanced peripheral vascular disease and cardiac disease are the most common barriers to kidney transplantation in the elderly. In addition, smoking and obesity may be more important relative contraindications for the elderly (88).

As the population with ESKD has increased, the supply of kidneys has not met demand (88). Practices in the United States and internationally have evolved to meet this demand by creating the expanded criteria donors (ECD) list, a full description of which is beyond the scope of this chapter (88). Port et al.’s (97) analysis of U.S. kidney transplant recipients from 1995 to 2000 shows that it takes 1.5 years for patients to achieve better outcomes from ECD kidneys than from dialysis alone, and Ojo (98) demonstrates that an ECD kidney transplanted to recipients older than 65 years results in 3.8 years of projected additional life span. A recent study by Molnar et al. (99) demonstrated that ECD kidneys were significant predictors of mortality in nonelderly patients (<70 years old), but in the elderly population, there were similar patient and graft survival outcomes when comparing ECD versus non-ECD allografts. It is recommended to use ECD kidneys in older patients, especially those with diabetes, who are shown to have increased benefit from reduced waiting time and may have shorter life expectancies, thereby maximizing the benefit of ECD kidneys (88,89,100).

DIALYSIS TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS

DIALYSIS TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Hemodialysis Vascular Access

Following the publication of the first National Kidney Foundation (NKF) Clinical Practice Guideline on vascular access in 2001 (101), the 2005 Fistula First initiative in the United States was promoted as a means to “substantially improve the health of Americans who need kidney dialysis or transplantation” (102). Although fistula rates in the United States increased subsequent to these campaigns, much of this rise is attributable to a precipitous drop in arteriovenous graft (AVG) use with a much more modest decline in catheter use. From 1997 to 2013, fistula prevalence increased from 24% to 68% with a decline in AVG use from 49% to 18% and catheter use from 27% to 15% (103). This has led to a call for a “catheter last” rather than just a “fistula first” strategy (104).

Despite success in increasing fistula prevalence, little progress has been made in reducing catheter use among incident HD patients. In an analysis of the DOPPS from 2012 to 2014, 67% of patients in the United States initiated HD with a catheter, 28% with a fistula, and 5% with an AVG (103). More concerning is the relatively low rate of conversion to use of a graft or fistula, particularly among the elderly. In a report from Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services ESKD Clinical Performance Project, among individuals who initiated with a catheter, 59% were still catheter dependent, while 15% had transitioned to a fistula and 25% to a graft after 3 months. Critical within this report is that, in adjusted analyses, individuals younger than 50 years had a twofold increased likelihood of converting to arteriovenous fistula (AVF) use compared with patients older than 75 years [odds ratio (OR) 2.14, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.40 to 3.28], whereas patients between 65 and 74 years of age were 39% more likely to convert to AVG use than continue to use a central venous catheter compared with patients older than 75 years (OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.92) (105).

In this section, the advantages, disadvantages, and special issues associated with permanent vascular access methods in the elderly HD patient are discussed.

Fistulas

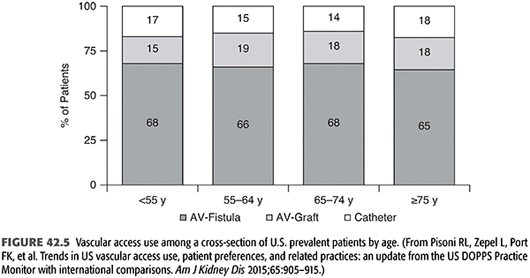

Multiple recent studies have focused on the question of ideal HD vascular access in the elderly as there are notable differences in this population compared to younger counterparts. Because of the high prevalence of diabetes, chronic hypertension, and both atherosclerosis and arteriosclerosis, the vascular substrate for access creation is certainly less satisfactory than that in younger patients (106). Not surprisingly, fistulas are less prevalent and catheters are more prevalent in elderly U.S. dialysis patients (FIGURE 42.5).

Current Kidney Disease Outcome Quality Initiative (KDOQI) recommendations suggest that a fistula should be placed at least 6 months before the anticipated start of HD treatments. This time frame is suggested to allow for both initial access evaluation as well as additional time for revision to ensure that a working fistula is available at initiation of dialysis therapy (107). In general, a working fistula must have the following characteristics: blood flow adequate to support dialysis (generally greater than 600 mL/min); a diameter greater than 0.6 cm, with location accessible for cannulation and discernible margins to allow for repetitive cannulation; and a depth of approximately 0.6 cm (ideally, between 0.5 to 1.0 cm from the skin surface). Determination of whether a fistula is likely to function may take up to 2 months, and adequate maturity for cannulation as much as 4 months, particularly with upper arm access in individuals with small veins at baseline. Not unexpectedly, the primary failure rate of fistulas may be higher in elderly patients and further attempts at fistula creation may be needed, resulting in a longer duration from initial fistula creation to successful fistula use. It is easy to foresee that this process may take a year or more, even with a dedicated access team. Does this mean that fistula creation should occur even earlier in the elderly? On an individual patient level, it makes sense—the earlier the fistula creation, the more attempts can be made to obtain successful access. However, particularly in the elderly, the earlier a fistula is created, the more likely it is that a patient will die of other causes before requiring dialysis (108). The competing risk of death increases with increasing age; Lee et al. (109) found in a cohort of 3,418 elderly (>70 years old) CKD patients who had predialysis access created, 67% started dialysis within 2 years. However, when stratified further by age, 69% of those aged 70 to 74 years initiated dialysis within 2 years with only 12% dying before requiring dialysis, while for those over the age of 85, 21.9% died before requiring dialysis with 60% initiating dialysis within the 2-year follow-up period (109). Furthermore, a recent study evaluating the optimal timing of fistula placement in the elderly concluded that there appears to be little benefit of placing access more than 6 to 9 months prior to anticipated need to start dialysis. The likelihood of initiating dialysis with a functioning fistula increased with fistula creation greater than 3 to 6 months prior to starting dialysis but plateaued after the 6- to 9-month range. In addition, the number of interventional access procedures increased over time, greatest in those who had fistulas placed >12 months predialysis (110). In another study of individuals 75 years and older, the number of access surgeries needed to allow one elder to initiate dialysis with a functioning fistula ranged from 8 to 12 procedures when surgery was performed at a GFR of 25 mL/min/1.73 m2 or lower to two to three surgeries at a threshold of 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 within a 6-month time frame (108).

A large study of fistula placement in an elderly population retrospectively evaluated access success among 196 patients aged 65 years and older and 248 patients younger than 65 years (111). There was a 64.8% primary and 75.1% cumulative fistula patency at 1 year among patients 65 years and older. This was comparable to that seen in younger patients. However, fistulas in the elderly group were more likely to have maturation failure with a relative risk of 1.7 compared to the <65 group. It is notable that analysis by anatomic type showed better survival of radiocephalic fistulas in the younger cohort, which had been described previously (112).

Fistula success can be maintained in an elderly population. Although Leapman et al. (113) demonstrated only 40% patency rates at 1 year among patients 70 years or older, many others reported better results. Wing et al. (114) reported 80% 1-year fistula survival in individuals older than 65 years, whereas Berardinelli et al. (112) described 78% 3-year patency for upper arm fistulas and 57% patency for forearm fistulas. Konner et al. (115) describe excellent 1-year primary access survival of first AVFs for nondiabetic patients 65 years and older (73% for women, 77% for men) and diabetic patients 65 years and older (78% women, 81% men) with use of either forearm AVFs or perforating vein or nonperforating vein fistulas at the elbow.

Grafts

Prosthetic grafts have a higher stenosis rate and a higher infection rate than AVFs (see Chapter 3) (106). The most common cause of graft loss is uncorrected stenosis with associated thrombosis (116). This is probably not different in the elderly. As in younger patients, it is vital to look for underlying cause(s) of thrombosis and try to correct them (16,106,117). Although KDOQI guidelines favor active access monitoring of AVGs, small studies have failed to show a consistent benefit in graft survival.

Tunneled Catheters

An indwelling central double-lumen cuffed catheter or twin single-lumen tunneled cuffed catheters may be the preferred intermediate or long-term access for some patients (118,119), in particular, those individuals who lack adequate vessels for fistula or graft creation, individuals with limited life expectancy, and individuals prone to steal syndrome with severe high-output heart failure unable to tolerate AVFs or grafts; these situations are all more common in the elderly than in younger patients.

One Strategy for Access in Geriatric Dialysis Patients

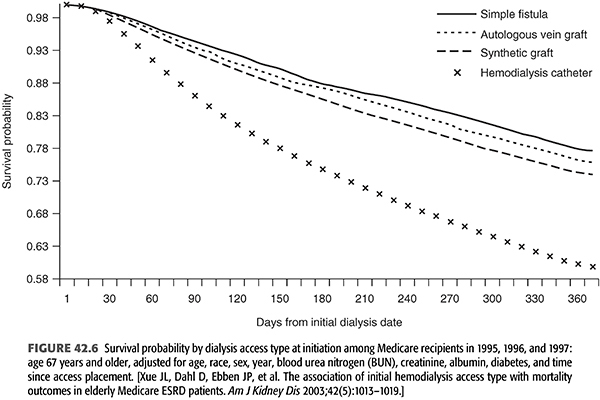

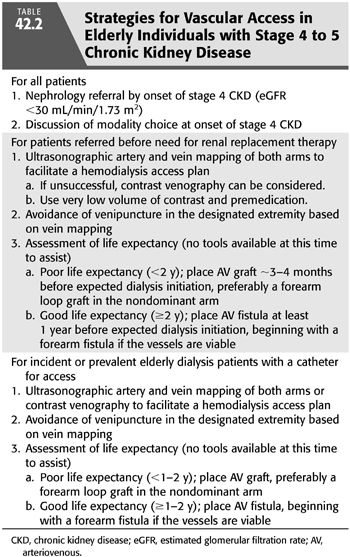

There are no clinical trials to guide therapeutic decisions for dialysis access in the elderly. Numerous studies have found that survival among incident dialysis patients with a functioning AVF is superior to that with a catheter or graft; however, survival with a graft is far superior to that with a catheter (FIGURE 42.6) (120). A large recent analysis of outcomes in elderly patients (>67 years old) based on predialysis access placement found no significant mortality difference between those patients who had a fistula placed as initial access versus those with AVG placement (121). When stratified further by age, it appeared there was a survival benefit for those ages 67 to 79 years with initial fistula placement compared with those with an AVG, but this disappeared in those greater than 80 years old. Importantly, of those with a fistula as their predialysis access, only 50.7% initiated dialysis with an AVF, the remainder required catheter placement. In those with an AVG as predialysis access, only 25.4% required conversion to catheter at time of dialysis initiation. This increased conversion to catheter use likely limits the prior benefits associated with “Fistula First” in the elderly. Another key variable as described by O’Hare et al. (108) is that many elderly individuals either do not progress to kidney failure or die before requiring dialysis. On the basis of clinical experience, observational data, and KDOQI guidelines, the authors favor the approach presented in TABLE 42.2 for individuals receiving care before kidney failure, taking into consideration life expectancy and expected time until dialysis will be required. This strategy should allow for at least one revision in the setting of primary access failure and allows the surgeons to progressively work their way up the arm. Finally, although a forearm access may not become usable for dialysis, often times in the setting of inflow stenosis, early creation may facilitate more rapid maturation of an upper arm outflow vein, especially when anastomosed to the larger caliber upper arm brachial artery.

A similar approach can be taken in elderly individuals initiating dialysis with a catheter, especially as it was demonstrated in a post hoc analysis of Hemodialysis (HEMO) Study data that changing vascular access type from a catheter to a fistula or graft was associated with a substantially lower risk for mortality compared with continuous use of a catheter, whereas changing from a fistula or graft to a catheter was associated with more than a twofold greater death rate compared with patients who used a fistula or a graft throughout the study (122). A strategy for incident or prevalent elderly dialysis patients with a catheter for access is also summarized in TABLE 42.2. The rationale behind these time frames is that the median survival of an AVG for individuals initiating dialysis with a functioning graft is more than 1 year (123), indicating that in individuals with limited life expectancy, it may be a beneficial trade-off to have higher initial success rates as seen with grafts than higher long-term access survival rates seen with a fistula.

Peritoneal Dialysis Access and Performance

Catheter Survival

In the early days of CAPD experience (1982), Ponce et al. (124) found decreased 2-year peritoneal catheter survival (67% vs. 78%) and increased pericatheter dialysate leakage (42.3% vs. 26.9%) in patients older than 60 years compared with younger patients. They hypothesized that the difference was secondary to “loose abdominal walls.” Because more than 90% of dialysate leaks occurred within the first week of insertion (catheters were used immediately) and leakage resolved if the catheter was not used for 1 to 2 weeks, catheters are usually inserted 2 to 3 weeks before use, with temporary HD if necessary, until the insertion site is completely healed. If it is necessary to use the catheter earlier, small frequent exchanges are employed with the patient in the supine position, gradually increasing in volume once integrity has been established (10).

Contrary to earlier findings, recent studies support the finding that catheter survival is either equivalent or improved in older versus younger patients (65,125,126). Kim et al. (127), in a retrospective multiyear comparison of peritoneal catheter survival with arteriovenous access, found greater long-term peritoneal access than arteriovenous access patency, particularly in diabetic patients and the elderly. Gentile (125) observed fewer catheter-related complications in elderly patients than in younger patients.

Peritonitis

Several large studies reveal no differences in peritonitis rates between young and old PD patients (10,65,125,126,128–130). Nissenson et al. (126), in a large two-center study, reported that after 1 year of CAPD, 60% of patients younger than 60 years were free of peritonitis versus 65% of the patients older than 60 years. At 3 years, the figures were 38% and 46%, respectively, and at 7 years, 30% and 38%. Nolph et al. (128) found an increased incidence of peritonitis in bedridden patients, although there was no increase in exit-site and tunnel infection rates or catheter replacements. A recent study evaluated first year outcomes in incident peritoneal dialysis patients and reported the highest rate of peritonitis among those aged 55 to 65 years old (43 per 100 patient-years) with lower rates in those younger than 55 and older than 65 years (131). See Chapter 37 for further discussion of peritonitis in CAPD patients.

Exit-Site and Tunnel Infections

There is little difference in exit-site infection rates (10,128), tunnel infections (65,128), or dialysate drainage pain in young versus elderly CAPD patients (10,132).

Adequacy

Poor adequacy may be related to poor drainage. This may be commonly caused by constipation in the elderly and can be treated with laxatives or catheter reinsertion. There are no reports as to differences in membrane characteristics by age.

Automated Peritoneal Dialysis

The use of automated or assisted PD can facilitate the use of this therapy even in patients with apraxia, cognitive difficulties, or even a person with disability treated either at home or at a nursing home.

SPECIAL SITUATIONS IN THE ELDERLY DIALYSIS PATIENT

SPECIAL SITUATIONS IN THE ELDERLY DIALYSIS PATIENT

Compliance with Therapy

There are little data evaluating compliance with dialysis prescriptions and lifestyle among the elderly. Recently, however, a recent large retrospective study of over 180,000 HD patients found that missed treatments were more frequent among younger patients (133). Avram et al. (134) describe a positive correlation between increased age and lower intradialytic weight gain, lower serum creatinine, and lower urea generation rate for both HD and PD patients, whereas McKevitt et al. (135) noted that dialysis patients aged 60 years and older demonstrated good compliance with potassium restriction, fair to good compliance for serum phosphorus, and fair to poor compliance with fluid restriction. Many factors may influence compliance among the elderly. These include cognitive impairment, visual impairment, depression, and social support. Therefore, individualized approaches to compliance and social support for the elderly dialysis patient, including evaluation of physiologic and psychosocial factors are essential for dialysis success (135–137).

Infection

Abnormalities of Immune Function with Aging

The altered immune status of uremia (138,139) is complicated in many elderly patients by similar changes in the immune system that may occur with aging, including increased susceptibility to infection and malignancy (140), and abnormalities in lymphocyte function and cell-mediated and humoral immunity (141,142). Whether there is a specific interaction with age, such that the double hit of uremia and aging synergistically enhances the risk of infection, is unknown. Whereas an older Israeli study found that infection was the most common cause of death in patients beginning dialysis at age 80 years or older, USRDS data reveal that, among prevalent U.S. dialysis patients aged 75 years and older, cardiovascular disease was 4 times more often the cause of death than infection from 2010 to 2012 (20,143).

Manifestations of Infection in the Elderly

In addition to changes in immune responsiveness, the presentation of infection in elderly patients is often subtle (see Chapter 37). The elderly patient may not manifest fever or leukocytosis, and even severe processes like acute abdomens may have less apparent manifestations. Similarly, elderly dialysis patients may manifest occult infection in subtle ways, including anorexia, apparent depression, vague feelings of malaise, apparent development of dementia, or decreased ability to cope with the usual activities of daily living. Occasionally, the only indication of infection is an increase in predialysis blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels without any apparent change in clinical status (144). Notably, urinary tract infections are common in the elderly but may be overlooked as a potential source in dialysis patients (145,146). Successful treatment of infection is generally associated with a return to the previous level of function.

Nutrition

Nutrition and Outcomes

It is particularly important to emphasize adequate nutrition in the older dialysis patient. The presence of protein-energy wasting and serum albumin levels have been shown to be independent predictors of mortality in dialysis patients (147). Both serum albumin and prealbumin predict hospitalization and mortality due to infection (148). Whether reduced nutritional indices are a marker of infection or indicate individuals predisposed to infection is unknown, although Kalantar-Zadeh and Kopple (149) postulate the existence of a “malnutrition inflammation complex syndrome” in maintenance dialysis patients with protein-energy malnutrition that predisposes to illness and infection and leads to poor quality of life and increased morbidity and mortality.

Strategies to Enhance Nutrition in Elderly Dialysis Patients

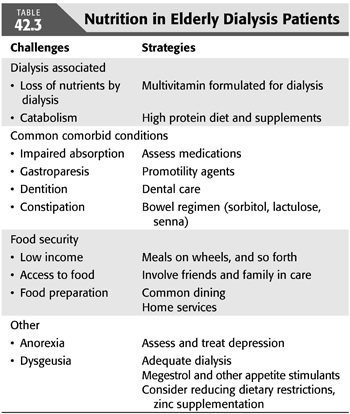

Some causes of nutritional impairment and strategies to enhance good nutrition in elderly dialysis patients are listed in TABLE 42.3 (150). Many of these strategies are self-explanatory. Patients who are disabled or living alone may benefit from programs such as meals-on-wheels, which deliver one or two prepared meals per day to the patient’s home and can accommodate a prescribed diet. Home assistance services that provide aides to prepare meals, shop for groceries, and/or provide companionship can be very helpful. Patients with poor intake may benefit from liberalized diets at the expense of permitting higher potassium and/or phosphate levels. The benefit of oral intradialytic nutritional supplementation remains controversial, but more recent observational data demonstrate an association between protein supplementation and reduced mortality, irrespective of serum albumin levels (151). Patients with diabetic gastroparesis may benefit from metoclopramide, 5 to 10 mg orally administered 30 minutes before meals. Zinc deficiency can occur in dialysis patients and may be associated with dysgeusia; supplementation may enhance the taste of food (152). Megestrol acetate can stimulate appetite in selected patients (153). Good oral hygiene is also very important. It is difficult for elderly patients to eat properly if they have sore gums, poor dentition, or poorly fitting dentures. Depression and constipation, both of which inhibit appetite, must also be treated. Finally, a thorough review of the patient’s medication list may reveal a large number of prescribed pills. Consolidating or eliminating unnecessary and less necessary medications may be associated with improved appetite.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree