The Express Procedures for Full Thickness Rectal Prolapse and Rectal Intussusception with or Without Rectocele Repair

Norman S. Williams

Christopher L.H. Chan

Introduction

Posterior pelvic compartment dysfunction is a challenging problem as appropriate therapies are limited. Management is often conservative, and surgery only indicated for very select groups including prolapsing disorders of the rectal wall. These disorders of the rectal wall: overt rectal prolapse, rectal intussusception (RI), and rectocele, are usually seen in females. The etiology is poorly understood but is likely to be associated with obstetric injury with pelvic tissue atrophy. One surgical strategy to correct these prolapsing disorders involves suspension of the rectum to a fixed point using synthetic or biological implants.

The EXPRESS procedure has been developed in an attempt to further improve outcomes following surgery in patients with prolapsing disorders of the rectal wall. It is a novel, relatively minimally invasive form of anterior rectopexy, using a perineal rather than abdominal approach, with the aid of a dermal porcine implant.

Biological Implants

The use of implants in surgery has become increasingly frequent over the last century, particularly polypropylene-based meshes in the management of abdominal wall defects/hernias. The disadvantage, however, of synthetic meshes in particular reference to colorectal surgery has been the well-documented risks of infection, extrusion, and fistulation (1,2). With these concerns biological implants have been introduced. They are

predominantly derived from porcine dermis, due to its similarity in structure to human dermis.

predominantly derived from porcine dermis, due to its similarity in structure to human dermis.

One such commercially available porcine dermal implant is Permacol™ (Covidien, MA, USA), an acellular cross-linked porcine collagen. The cross linking prevents degradation by collagenases and it is therefore theoretically permanent once implanted. It also elicits a very mild inflammatory response, with minimal fibrosis, and can be successfully used to reconstruct defects within infected fields. In addition, histological studies have demonstrated the implant to be associated with ordered neocollagen deposition presumed to result in greater tissue strength than at the time of implantation (3). These characteristics make Permacol™ an ideal implant to utilize in surgery for pelvic disorders, particularly those of the posterior compartment, which require any implant to be placed in close proximity to the rectum.

Rectal Intussusception and Rectocele

Rectal evacuatory disorder/dysfunction (RED) is a complex problem where the primary abnormality is the preferential storage of residue in the rectum for prolonged periods, with the inability to evacuate this residue adequately. The pathophysiologies that underlie RED are not well understood as the etiology is varied: anatomical disorders of the rectum, for example, megarectum and prolapsing disorders of the rectal wall, for example, RI and rectocele. Rectal intussusception can be defined as a full thickness invagination of the rectal wall, which is thought to cause symptoms by impeding the evacuation of the rectum either by occlusion of the rectal lumen (recto-rectal) or the anal canal (recto-anal). Furthermore, the presence of the intussusception, particularly in the upper anal canal, may result in a sense of incomplete evacuation despite adequate clearance of rectal contents. However, the significance of RI is not fully understood due to its presence in studies of asymptomatic volunteers, albeit in a less severe form (4). Commonly associated with RI is a rectocele, a ballooning of the anterior rectum into the posterior vaginal wall resulting in trapping of rectal contents thus contributing to symptoms of evacuatory dysfunction.

There are few described procedures for a surgical repair of RI (5), and can be divided into resectional, intra-rectal Delorme’s, stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) procedure, or suspensory techniques, such as the various forms of abdominal rectopexy. Most, however, are universally associated with poor functional outcomes (6), or serious complications (7,8).

With these limitations in mind we have developed an innovative minimally invasive technique that combines the advantages of abdominal rectopexy procedures, namely, lower recurrence rates, with the advantages of perineal approaches, lower morbidity, and ability to repair a coexistent rectocele. The EXternal Pelvic REctal SuSpension (EXPRESS) is essentially an anterior perineal rectopexy, which involves fixation of the rectum to the periosteum of the superior pubic ramus with or without simultaneous reinforcement of the rectovaginal septum with a Permacol™ patch, to correct any coexistent rectocele.

Express for Rectal Intussusception

Indications

Patients with severe rectal evacuatory dysfunction refractory to maximal conservative therapy and a normal colonic transit with:

Full-thickness internal rectal circumferential prolapse (rectal intussusception) (Shorvon grade 4 or more) impeding rectal emptying on defecography ± functional

rectocele (more than 2 cm) containing residual barium termination of rectal evacuation during defecography.

Patients with symptoms including tenesmus or the sensation of a lump within the rectum after defecation (in association with an intussusception) and/or an uncomfortable swelling within the vagina, or the need for vaginal digitation (in association with a rectocele) may also be considered for surgery.

Contraindications

Patients younger than age 18 years

Unfit for surgery

Delayed colonic transit and/or rectal hyposensitivity

Preoperative

Patients are carefully selected for the procedure on the basis of symptom profile, clinical examination, and indications stated above. Patients with severe RED (symptoms of tenesmus, something coming down, or a sensation of a lump within the rectum (associated with RI) and/or an uncomfortable swelling in the vagina or a need for vaginal digitation (in association with rectocele) are considered for the procedure only after concomitant organic pathology has been excluded.

Comprehensive anorectal physiologic investigations should be performed in all patients, to include diagnostic defecography and assessment of anal sphincter function and integrity, using manometry and endoanal ultrasound respectively. Rectal sensory thresholds to balloon distension, evaluation of pudendal nerve terminal motor latencies, and assessment of colonic transit using a simple radio-opaque marker study are undertaken.

In addition, all patients must have initially undergone a period of maximal conservative therapy tailored to their presenting symptoms and physiologic findings, which is coordinated by a nurse specialist. This incorporates psychosocial counseling, optimization of diet and lifestyle, optimization of medication, pelvic floor coordination exercises, and true biofeedback techniques (including balloon expulsion). Only patients who fail to respond to this therapeutic program are considered for surgery.

Surgery

Positioning

The patient is placed in a modified Lloyd-Davies position on the operating table, with pneumatic compression stockings to reduce the risk of thromboembolism. A urethral catheter is inserted to empty the bladder and the skin is prepared and draped to allow access to the perineum as well as the suprapubic region.

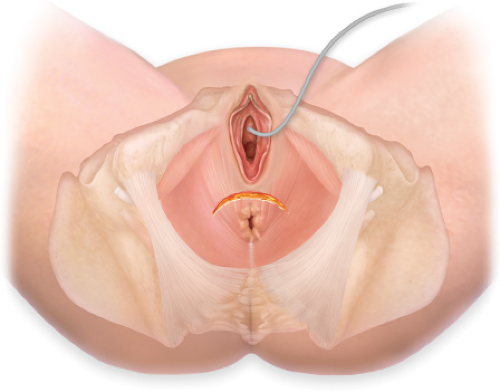

A convex crescentic incision is made between the rectum and the vagina/scrotum (Fig. 37.1). The skin and subcutaneous tissue are dissected from the underlying anterior sphincter complex so as to not damage the anterior aspect, thus enabling entry into the extra sphincteric plane. The plane between the posterior wall of the vagina and the anterior wall of the rectum is entered taking care not to injure the sphincter complex or buttonhole the rectum or vagina. Infiltration with saline solution aids in development of this plane. The dissection is continued cephalad as far as the posterior fornix of the vagina to the level of Denonvilliers’ fascia (Fig. 37.2). Once the anterior plane has been dissected satisfactorily, the lateral wall of the rectum can be mobilized using blunt dissection.

Although the operation is much more commonly performed in women, the procedure can be applied to male patients. The dissection in the male resembles that of a perineal prostatectomy in which the rectourethral/prostatic plane is entered by dividing

the rectourethralis muscle close to the rectum. The anterior rectal wall is then mobilized, using a combination of blunt and diathermy dissection, from the prostate in close proximity to the rectum to avoid damage to the neurovascular bundles located at the inferolateral aspect of the prostate.

the rectourethralis muscle close to the rectum. The anterior rectal wall is then mobilized, using a combination of blunt and diathermy dissection, from the prostate in close proximity to the rectum to avoid damage to the neurovascular bundles located at the inferolateral aspect of the prostate.

The assistant makes two transverse incisions over the lateral aspects of the superior pubic rami 2–3 cm long. The dissection is deepened to gain access to the retropubic space bilaterally. A custom made tunneller is advanced through the perineal incision

retropubically; care is taken not to damage the vagina at this point, and delivered through the suprapubic incisions (Fig. 37.3). Two T-shaped strips of Permacol™ are utilized for the rectal suspension. The corner of the transverse portion of the T-piece is sutured to a specially designed olive, which can be secured to the end of the tunnelling device and then delivered through the retropubic tunnel back into the perineal wound (Fig. 37.4).

retropubically; care is taken not to damage the vagina at this point, and delivered through the suprapubic incisions (Fig. 37.3). Two T-shaped strips of Permacol™ are utilized for the rectal suspension. The corner of the transverse portion of the T-piece is sutured to a specially designed olive, which can be secured to the end of the tunnelling device and then delivered through the retropubic tunnel back into the perineal wound (Fig. 37.4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree