BUSINESS AS USUAL

The majority of physicians have little to no formal training in business or business principles. As mentioned earlier, this was not necessary or relevant to running a successful practice. With robust reimbursement for skills learned in medical school and honed in residency and fellowship training, most practices had no business structures. Practices consisted of what I call a Marcus Welby (3) structure, front office staff answering phones, checking patients in and out, and medical assistants placing patients in rooms and billing staff. There were no business processes, protocols, measures of practice success, nor the expertise needed to keep abreast of the increasingly complex billing and coding requirements. Governance structure often rested with the most senior rather than most capable physician and rarely did nonphysician business savvy employees participate. Data collection, either on patient-centric information or on basic business metrics, was nonexistent. Inefficiency was the standard. Patient care was rendered one on one, by the physician, delivered to each patient as they were seen. Little focus on education, prevention, or population health was present. Marketing was by reputation alone or word of mouth and was more often based on who you were rather than your capabilities. Your “success” in the eyes of a hospital administrator was solely predicated on your ability to admit as many patients as possible. From a purely business perspective—this is a receipt for disaster, one that has now come due.

CHANGING TIDE

CHANGING TIDE

As noted above, since 1972 when Congress passed the Social Security Amendments allowing for coverage of ESKD for all patient services irrespective of age, the number of patients and costs incurred in their care has increased dramatically. Most recent United States Renal Data System (USRDS) data reports that ESKD patients make up 1% of Medicare beneficiaries and consume 5.6% of all Medicare dollars (4). Anemic reimbursement updates over the past 20 years have resulted in ESKD provider consolidation that successfully drove economies of scale in a fee-for-service (FFS) world (5). Although there have been substantial and complex changes in reimbursement under this model, most recently moving to a partially bundled payment model, the end result was business survival favored large integrated providers with the top two now representing over 70% of all ESKD patients in the United States. Predictably, their market power influences payers: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and legislators, in ways not available/accessible to the average nephrologist. These realities are influencing the business of the practice nephrology in ways never envisioned before.

If the previous paragraph represents the “macrocosm” of the business of nephrology, the “microcosm” of nephrology (nephrology practices) has also been impacted by the economic impact of legislation passed to influence rising overall health costs. In 2008, Congress passed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) (6). This legislation was a game changer for all of health care impacting how hospitals, insurers, and health care providers rendered care and ran their businesses. Forgoing the dominant FFS payment model for a value-based reimbursement (VBR) model, this legislation, as yet unproven in its benefits, has placed disproportional burdens on medical practices challenging the practice models, or lack thereof, on which they were built.

The PPACA granted a windfall of power to hospitals via accountable care organizations (ACOs). ACOs, population risk vehicles, have driven hospital consolidation into mega-health care systems to mitigate this risk. Physicians, faced with little to no ability to compete in this space, quickly became hospital employed, primary care first, followed by high-revenue subspecialists (oncology, cardiology, orthopedics) all who recently saw their outpatient procedure reimbursement gutted, destroying practice models that had sustained them for years. The hospital strategy is to create seamless care models over wide geographies and manage risk by serving large populations while controlling and directing physician care, hoping to link this to higher care quality and therefore—value.

Although one may quibble over the details or the wisdom of this approach, given how the PPACA is constructed, this scenario is predictably rapidly gaining ground.

Given these realities, the practice of nephrology, or better stated, the business of practicing nephrology must rapidly digest this information and access its business options to survive.

ACCESSING YOUR BUSINESS

ACCESSING YOUR BUSINESS

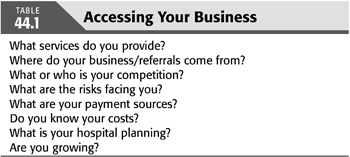

The first step in the process of remaining competitive in a changing reimbursement environment is to better understand your business. TABLE 44.1 provides some critical questions you should ask yourself. But basically, you need to do a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threat) analysis (7). Although beyond the scope of this chapter, a SWOT analysis is a simple, powerful, and insightful business tool. Block off time, without distraction, to list as many ideas for each category as you can.

There are several items that you will identify in your SWOT analysis worth focusing on; a few high-level items are discussed here.

One item is the practices’ internal business structure. How is your practice managed? What is the governance structure? How are decisions made, and by whom? Who operationalizes change within the practice? Is it measured? Without a strong governance structure, the ability to rapidly implement change is limited and will negatively impact any meaningful and necessary change.

What business reports are available? How often are they produced? Who produces them? What information are they providing to you? Do you have business partners? Hospitals, dialysis providers, large primary care provider groups? Are you nurturing these relationships?

Understanding the importance of these questions will be critical for the practice to be credible to outsider providers, in recruiting new physicians, to make decisions quickly and nimbly, and to develop and implement process changes in how clinical services are provided.

Another item to consider is, where do your business/patient referrals come from? In the past, direct relationships with referral sources ruled. That pattern has been rapidly eroded. For the most part, your primary care referral sources no longer round in the hospital, a major source of patient referrals; rather, they outsource this work to hospitalists to better focus on their outpatient patient care. Hospitalists remain a moving target with high turnover, making development of a referral relationship with them challenging; often, there is a generational separation from you, and they tend to be looking for very specific renal services from your practice. Are you meeting that need? Also, direct relationships with insurers/payers are becoming more common and are often tied to risk contracts.

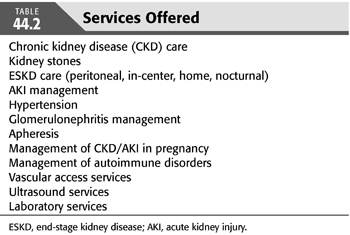

In the broadest sense, you should determine exactly what services you offer. TABLE 44.2 lists a few. Importantly, do you know what it costs to provide these services? If you do not know what it costs you to deliver, let us say, CKD stage 4 care, in your office, how can you negotiate payment from insurers? Or how can you render that service more economically? Developing a list of services and understanding their costs will serve you well in measuring, marketing, and reporting outcomes.

According to the RPA’s (2) 2014 Benchmarking survey, 40% to 50% of a nephrologist’s income comes from ESKD care and medical directorships, 30% from hospital work, and the remainder from the office. Each of these “business lanes” needs to be separately analyzed for growth, profitability, and sustainability.

The following sections describe details on nephrology-specific business care lanes that can be a focus of your practice analysis with conclusions drawn specifically to the VBR future for all of health care.

PRACTICE CLINICAL AND BUSINESS STRUCTURES

PRACTICE CLINICAL AND BUSINESS STRUCTURES

Nephrology practices are structured in three clinical and four business domains. The clinical domains include hospital services, dialysis services, and office/clinic practice. The business domains include these three plus ancillary nephrology services. Ancillary services traditionally include research, laboratory services, dialysis facility joint ventures or direct ownership, real estate, and vascular access centers, each with their own unique reimbursement and business challenges and are beyond the scope of this chapter. The ability of practices to participate in ancillary services varies from practice to practice and is heavily weighted on practice size, patient density, financial resources, and the practice leaderships’ desire to expand into other areas.

The financial viability of the four business domains has historically been predicated on FFS and therefore high patient volumes and market share. Each domain existed in isolation resulting in the fragmented delivery of renal services and, excepting ESKD, had little quality oversight and was innately inefficient.

As mentioned earlier, the PPACA is influencing all of these domains and must be considered in your business planning moving forward.

FINANCIAL MODELS

FINANCIAL MODELS

The best example of a mature business/economic model of renal care is that of ESKD. For greater than 30 years, a focus on ESKD care has created precise financial models. Ease of identifying patients with ESKD, incident rates, defined payment for treatment, known hospitalization, and mortality rates have all allowed this medical industry to prosper and grow. Much less focus and data exists for CKD patients who have been, for all intents and purposes, an FFS payment model. Valid arguments have been made that without viable financial models for CKD patients, providers, out of financial necessity, will continue to apply disproportional resources to ESKD. The PPACA changed the focus in all of health care, targeting health care value rather than care volume. This game changing concept was best summed up by then CMS director, Donald Berwick, in his “triple aim of care”: improvement in the health of populations, improvement in the experience of care, and reducing health care costs (8). This creates an incentive to move the FFS CKD payment system to a value care model that may be linked to the totality of renal care potentially inclusive of ESKD care.

Creating a “value-based” model around kidney disease offers us an opportunity to uniquely offer to patients the benefits of Dr. Berwick’s triple aim of care. Unfortunately, our kidney care systems remain fragmented, and this creates real barriers that must first be surmounted to move forward in a meaningful way. Additionally, the capital investments necessary for this metamorphosis to occur is out of reach of most practices, necessitating the consideration of strategic partnerships for participation in this model of care. The reality remains though, that the future of the practice/business of nephrology will be linked to this expectation and any considerations of altering your practices’ business model must take this seriously.

END-STAGE KIDNEY DISEASE CARE

END-STAGE KIDNEY DISEASE CARE

ESKD care is, for the most part, provided by organized for-profit and not-for-profit providers in partnership with nephrologists (clinical care, medical directorships, and/or joint venture relationships). The greatest proportion of the practice income emanates for ESKD care, and therefore, much attention should be paid here as this income stream is under threat.

Medical directors fee contributes substantially to the practices’ income. CMS estimates that the roles and responsibilities contracted for these services consume approximately 25% of a nephrologist’s time. Therefore, the number of agreements one can provide will be under scrutiny, and this fact should be considered in their allocation within the practice.

Nephrologists are currently paid on an FFS model for incremental monthly clinical care (one visit, two to three visits, and four visits per month); this changed from the traditional monthly capitated payment not tied to frequency of visits in 2005 (9). The greater the number of patients under your care and the more efficiently you can deliver that care, the more financially successful the practice. This very model incentivizes increasing the volume of ESKD patients rather than delivering “upstream” value-based care that may negatively impact ESKD incident rates. Although it may seem counterintuitive, achieving and maintaining high ESKD patient volume is critical in a VBR model as more patients buffer the practices’ ability to accept risk contracts. Therefore, continued efforts at growth must not be ignored.

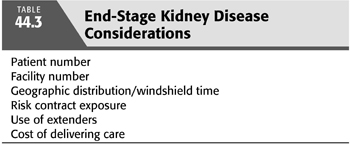

However, providing ESKD services in an economically viable manner include careful analysis of the number of patients, the number of dialysis facilities served, the geographic placement of these facilities, and travel time to each (TABLE 44.3). This “process of care” is under increased pressure as payments are now starting to be tied to risk models (see the following text), and the ability of physicians to render care personally is in question. Use of physician extenders to provide the noncomprehensive care visits and field questions from dialysis care staff frees the nephrologists’ time to focus on other practice business needs and should be considered. Recall, the ESKD population under the practices’ care has a specific quantifiable income and cost. These should be determined and monitored as a business metric.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree