Chapter 33 Technique of cholecystectomy

Overview

The indications for performing open cholecystectomy have evolved since the advent and widespread use of laparoscopic cholecystectomy (see Chapter 34). Surgeons are now trained in laparoscopy at the initiation and for the duration of their training. In fact, as the pendulum has swung so far toward performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, it may be argued that surgeons completing their training today are not appropriately versed in the techniques of the open operation, which ironically are most useful and best applied to the difficult gallbladder that is not amenable to laparoscopic excision. Along with discussing important anatomic and clinical considerations, this chapter focuses on three main techniques for performing open cholecystectomy: 1) retrograde, 2) anterograde (fundus-down), and 3) partial (subtotal) cholecystectomy for difficult situations.

Laparoscopic Versus Minilaparotomy Cholecystectomy

Any discussion of open cholecystectomy would be incomplete without briefly reviewing the major comparative studies that have addressed the different approaches mentioned above for removing the gallbladder. A small incision, or minilaparotomy, has been defined by most authors as an incision less than 8 cm in length. Many prospective randomized trials have compared the two techniques. Two such early studies were published in The Lancet in 1992 and 1994, and both reported advantages of the laparoscopic approach over a minilaparotomy, including shorter postoperative hospital stay and a decreased postoperative convalescence (Barkun et al, 1992; McMahon et al, 1994). However, a different conclusion was reported by Majeed and colleagues in 1996; they found no difference in hospital stay or time to return to work and full activity among patients who underwent cholecystectomy by the two techniques. Subsequent comparative analysis of the costs of laparoscopic versus small-incision cholecystectomy, based on the same population included in the Majeed study, suggested that small-incision cholecystectomy was less expensive than laparoscopic cholecystectomy (Calvert et al, 2000). This pattern of conflicting results has persisted in recent studies as well, as some trials report a benefit to the laparoscopic approach, but others report no difference, depending on the outcomes measured (Ros et al, 2001; Keus et al, 2008). Nevertheless, a market demand of sorts has popularized laparoscopic cholecystectomy as the technique of choice today.

Indications for Open Cholecystectomy

The introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy has significantly influenced the treatment of patients with gallstones, as evidenced by an increase of 20% to 30% in the total number of cholecystectomies performed (Schwesinger & Diehl, 1996). This increase was predominantly in patients with uncomplicated cholelithiasis and in those undergoing elective surgery (Shea et al, 1998). Although it is likely that considerations such as reduced postoperative discomfort and smaller scars have made the procedure more acceptable to patients with minor symptoms, it is worth raising caution that the indications for cholecystectomy should not be extended simply because a minimally invasive approach is available.

Cholecystectomy usually is performed for symptomatic cholelithiasis and for its related complications, such as obstructive jaundice or biliary pancreatitis. Cholecystectomy for acalculous cholecystitis, gallbladder adenoma, or suspected gallbladder carcinoma is less frequent, with the open technique more appropriate for suspected carcinoma. Asymptomatic cholelithiasis has been suggested as an indication for cholecystectomy in diabetic or immunocompromised patients, but this indication remains controversial (Schwesinger & Diehl, 1996). Postcholecystectomy pain, which has been observed in as many as 30% of cases, may be the consequence of an operation performed for symptoms unrelated to the presence of gallstones (Bodvall & Overgaard, 1967).

In a multivariate comparison of complications after laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy, the overall complication rate was found to be distinctly lower after the laparoscopic approach ( Jatzko et al, 1995). This finding was confirmed, and a lower mortality rate was observed, in a population-based cohort study comparing both surgical approaches (Zacks et al, 2002). However, in the laparoscopic era, it is exceedingly important to consider patient selection and preoperative factors when comparing the two techniques in a retrospective fashion. Wolf and colleagues (2009) recently reported on a single surgeon’s experience with open cholecystectomy over a 9-year period from 1997 to 2006. In this study, more than half (56%) of patients who underwent an open cholecystectomy were American Society of Anesthesiologists class III or IV compared with only 10% of those who underwent a laparoscopic procedure. Furthermore, nearly 10% of patients in the open cholecystectomy group had prior upper abdominal surgery, compared with only 1% of those in the laparoscopic group. These factors clearly predispose to the reported increase in morbidity and mortality rates associated with open cholecystectomy today.

Open cholecystectomy increasingly is performed only in cases in which laparoscopic techniques do not allow for a safe procedure or as part of a larger procedure, such as pancreaticoduodenectomy or partial hepatectomy. The presence of severe inflammation, such as in xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis (Guzman-Valdivia, 2005), or a concern for excessive bleeding in patients with cirrhotic portal hypertension are two examples of situations in which surgeons are much more likely to use the open technique. Although two prospective studies from centers where surgeons have considerable experience performing cholecystectomy in patients with cirrhotic portal hypertension have reported the feasibility and superiority of the laparoscopic approach in these patients (Ji et al, 2005; El-Awadi et al, 2009), it is the author’s opinion that most surgeons still opt for an open procedure. These difficult cases may be recognized preoperatively or during laparoscopy. It has been suggested, however, that attempts at performing a laparoscopic operation prior to converting to an open technique might increase the incidence of major complications (Wolf et al, 2009). Finally, as mentioned above, a gallbladder mass that is concerning for malignancy is usually better suited to an open procedure. Concern over intraoperative gallbladder perforation (Z’Graggen et al, 1998; Weiland et al, 2002), inadequate staging, and an incomplete resection with a laparoscopic procedure are some of the reasons to choose an open technique when carcinoma is suspected.

Preoperative Assessment

Some clinical features should alert the surgeon to possible operative difficulties. A history of repeated and prolonged attacks of right upper quadrant pain might be associated with chronic inflammation and dense adhesions or fibrous obliteration of the triangle of Calot. Liver function tests should be performed routinely before cholecystectomy. Any abnormality (i.e., elevation) of the serum bilirubin or alkaline phosphatase requires serious attention, because it may not be caused by the presence of stones in the bile duct but may be a sign of other extrahepatic biliary tract disease. Possibilities of such alternate diagnoses include Mirizzi syndrome (Chapters 35 and 42A); tumors of the gallbladder (Chapter 49), bile duct (Chapter 50B), or pancreas (Chapter 58A, Chapter 58B ); a choledochal cyst (Chapter 46); and sclerosing cholangitis (Chapter 41). Although patients who are submitted to cholecystectomy usually will have undergone ultrasonography, more detailed investigations should be performed if any doubt exists as to the integrity of the bile duct. Computed tomography (CT; see Chapter 16) and magnetic resonance imaging cholangiography (see Chapter 17) are the initial studies of choice. Should further diagnostic evaluation be necessary, endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (see Chapter 18) usually helps identify stones or other ductal abnormalities. Attention should be directed to any anatomic variants in the biliary system or extrahepatic vasculature that may be visualized on the above imaging modalities. A mild elevation of the aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) may also signify considerable pericholecystic inflammation causing localized hepatocellular necrosis. This scenario is particularly relevant in the elderly population, in diabetic patients, and in patients who are relatively immunocompromised with a history and physical exam that is not indicative of the underlying severe inflammation.

Operation

Anatomy

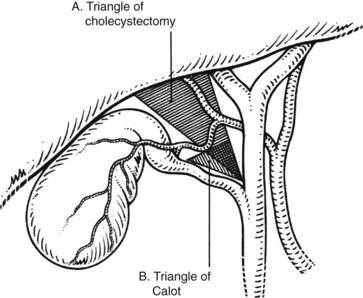

The triangle of Calot, first described in 1891, forms the basis of the anatomic dissection for performing safe cholecystectomy. As originally described, this triangle is formed by the cystic duct, common hepatic duct, and the cystic artery. A common misperception is that the superior border of this triangle is the inferior border of the liver. This, rather, is termed the triangle of cholecystectomy, and it has for its upper limit not the cystic artery but the inferior surface of the liver (Fig. 33.1; Rocko & Di Gioia, 1981). Routine meticulous dissection of this area will minimize iatrogenic injury and allow for safe cholecystectomy.

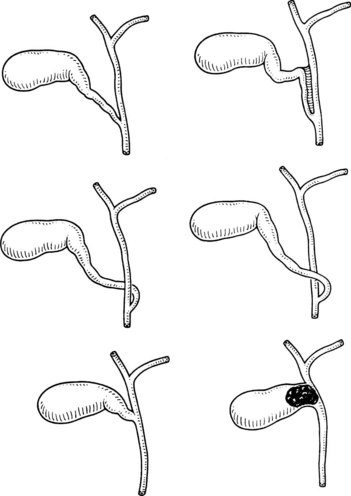

The normal location of the gallbladder neck and cystic duct junction is between the peritoneal surfaces within the right superior portion of the hepatoduodenal ligament. A variety of abnormalities can alter the standard anatomy or appearance of the gallbladder. A bilobar gallbladder or presence of septa usually is not relevant, as the gallbladder most often retains its normal location with respect to the liver and vital portal structures. Duplication of the gallbladder is rare and might be associated with one or two cystic ducts. Complete gallbladder agenesis is extremely rare, and the perceived absence of a gallbladder is most often associated with an intrahepatic location. In such cases, the gallbladder infundibulum is usually visualized extrahepatically. The gallbladder may be lying on the left side of a right-sided round ligament, still attached to the right side of the liver. In even rarer instances, the gallbladder has been observed attached to the left lobe of the liver, situated to the left of the round ligament (Fig. 33.2) (Fujita et al, 1998).

Variations in the junction between the cystic duct and common bile duct should be considered the rule rather than the exception in order to maintain a healthy respect for the anatomy and minimize iatrogenic injury during cholecystectomy (Figs. 33.3 and 33.4). The cystic duct may join the right side of the common bile duct after a long parallel course, or it may be very short and almost nonexistent. For the latter, it is imperative not to mistake the common bile duct for the cystic duct, which can lead to inadvertent ligation and division of the common bile duct. On the contrary, a perceived short cystic duct might actually be a long structure that is fused and running parallel to the common hepatic duct, or it may be draining directly into the right hepatic duct. The cystic duct also may empty into the left side of the hepatic duct, having crossed it anteriorly or posteriorly. The cystic duct occasionally may be contracted as a result of a chronic inflammatory process.

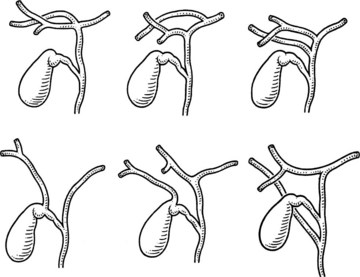

An unrecognized abnormal confluence of the hepatic ducts probably represents the most important source of error leading to damage to the biliary tract during cholecystectomy (see Chapter 42A). A common anomaly that is worth noting is an early takeoff of the right posterior sectoral bile duct from the common duct either just above or below the cystic duct insertion. This sectoral duct may be confused for the cystic duct as it travels just inferior to or through the triangle of Calot. Alternatively, the cystic duct may actually arise from the right posterior sectoral duct. An abnormal confluence of the hepatic ducts has been reported in 43% of cases, and a low-lying right posterior sectoral duct has been reported in up to 20% of cases (Couinaud, 1957; Puente & Bannura, 1983; Champetier et al, 1989; see Fig. 33.4).

Although the necessity to systematically perform intraoperative cholangiography has been controversial for decades (Talamini, 2003

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree