Fig. 18.1

Time-to-event curve showing cumulative incidence of pouch neoplasia (pouch cancer + pouch dysplasia) in 3,203 patients with inflammatory bowel disease and restorative proctocolectomy. Reprinted with permission from Kariv R, Remzi FH, Lian L, Bennett AE, Kiran RP, Kariv Y, Fazio VW, Lavery IC, Shen B. Preoperative colorectal neoplasia increases risk for pouch neoplasia in patients with restorative proctocolectomy. Gastroenterology 2010 Sep;139(3):806–12

A Dutch registry of 1,200 pouch patients found a prevalence of 1.83 % for pouch neoplasia [12]. The respective cumulative incidences at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years for pouch neoplasia was 1.0 %, 2.0 %, 3.7 %, and 6.9 % and 0.6 %, 1.4 %, 2.1 %, and 3.3 % for pouch adenocarcinoma [12] (Fig. 18.2).

Fig. 18.2

A Dutch registry of 1,200 pouch patients shows cumulative incidence of pouch neoplasia. Reprinted with permission from Derikx LA, Kievit W, Drenth JP, de Jong DJ, Ponsioen CY, Oldenburg B3 van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Dijkstra G, Grubben MJ, van Laarhoven CJ, Nagtegaal ID, Hoentjen F; Dutch Initiative on Crohn and Colitis. Prior colorectal neoplasia is associated with increased risk of ileoanal pouch neoplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2014 Jan;146(1):119–128

Typically, cases of cancer reported in the literature occurred more than 10 years after proctocolectomy, while dysplasia occurred earlier [11] (Figs. 18.3a, b, 18.4 and 18.5).

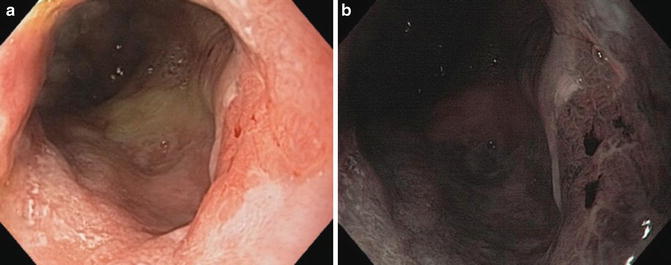

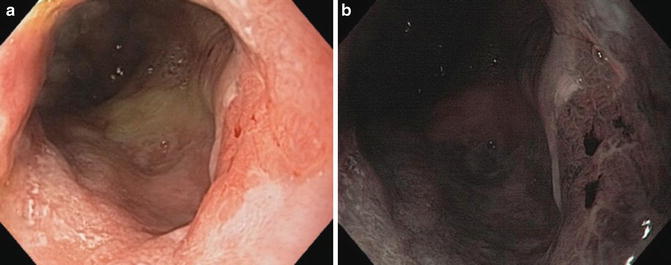

Fig. 18.3

(a) Cancer of the ATZ on the right side of the photo with white light imaging. (b) Cancer of the ATZ in the same patient with narrow band imaging

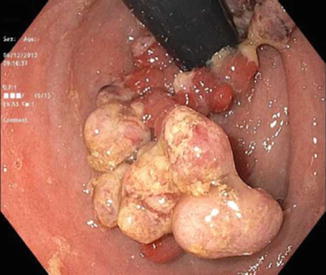

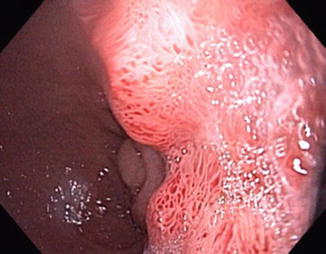

Fig. 18.4

Cancer of the ileal pouch

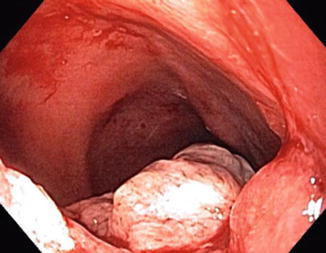

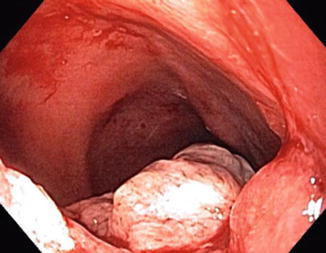

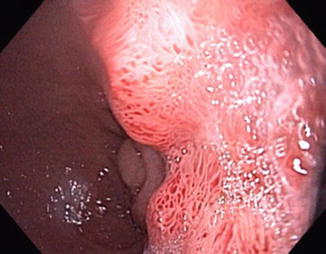

Fig. 18.5

Cancer of the ATZ extending into the pouch

Pouch neoplasia can be classified as follows [9–11]:

1.

Pouch dysplasia (Indefinite/low-grade/high-grade)

2.

Cuff dysplasia (Indefinite/low-grade/high grade)

3.

Pouch adenocarcinoma

4.

Cuff adenocarcinoma

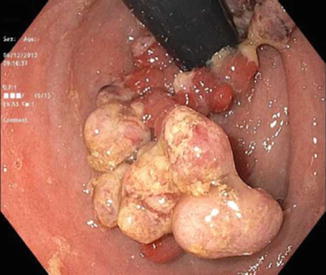

The diagnosis of pouch dysplasia should be confirmed by at least two expert gastrointestinal pathologists, as is done in IBD colonic biopsies with suspected dysplasia. Dysplasia can be flat or polypoid. Polypoid dysplasia can be further divided to a dysplasia-associated lesion or mass (DALM) (Fig. 18.6) or a pouch polyp with no surrounding dysplasia. Often, it is the endoscopic appearance of the dysplastic lesion that is used to distinguish the two types. Pouch and cuff dysplasia have been described to be equally prevalent in some studies [10] while others show that cuff dysplasia is significantly more common [11, 12]

Fig. 18.6

DALM lesion of the ATZ

There have been several suggested risk factors for pouch neoplasia. The most important is preoperative ulcerative colitis-associated cancer or dysplasia [9–12]. In both the Cleveland Clinic and Dutch cohorts, preoperative neoplasia was the single most important predictive factor for ileal pouch neoplasia with adjusted hazard ratios of 13.43 (95 % confidence interval (CI): 3.96–45.53) or 24.69 (95 % CI, 9.61–63.42) for prior carcinoma, and 3.62 (95 % CI: 1.59–8.23;) or 3.76 (95 % CI, 1.39–10.19) for prior dysplasia, in the two respective cohorts [11, 12].

Other suspected risk factors for pouch neoplasia, such as long duration of colitis prior to surgery, presence of primary sclerosing cholangitis, type of ileoanal anastomosis (double-stapled versus hand-sewn with mucosectomy), type C (atrophic) pouch mucosa, duration of postoperative follow-up, and chronic pouchitis were examined in pooled analyses, but have not shown consistent predictive ability. Interestingly, these suspected risk factors are still mentioned in some guidelines to suggest more intense surveillance [6]. Mucosectomy but has not been shown to be protective for ileal pouch and ATZ neoplasia [13].

Pouch Surveillance: An Unsolved Controversy

No guidelines specifically address pouch neoplasia surveillance or define risk groups for increased surveillance. The British Society of Gastroenterology suggests an annual pouch endoscopy for the following high-risk groups: previous rectal dysplasia, dysplasia/cancer at time of pouch surgery, PSC, or Type C mucosa of pouch (persistent atrophy, and severe inflammation) [5, 6]. Surveillance is recommended every 5 years in all others. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) guidelines do not address pouch endoscopic surveillance [4]. UpToDate suggests a surveillance pouchoscopy every 3–5 years in the absence of inflammation and atrophy [8]. However, in the presence of severe inflammation or atrophy, increasing surveillance to annual pouchoscopy is suggested.

A debate has been ongoing in regard to the clinical justification and cost-effectiveness of pouch surveillance [14–18]. A series of 138 asymptomatic pouch patients who underwent surveillance endoscopy of the pouch demonstrated indefinite dysplasia in only one case with no other neoplastic findings, although 50 % of the patients had endoscopic abnormalities [16]. Pouch polyps have been studied through a large pouch patient cohort [19]. Among 1,094 pouch patients, 96 (8.8 %) had pouch polyps, most (96.9 %) were inflammatory polyps while only 3 (3.1 %) were neoplastic polyps with low-grade or indefinite dysplasia.

A decision for pouch surveillance protocols should be based on the following parameters:

2.

Cost-effectiveness analysis of pouch surveillance was conducted for three risk-level populations: (1) average-risk patients with no preoperative colonic neoplasia; (2) above-average-risk patients (dysplasia of the colon as the indication for colectomy); (3) high-risk patients (cancer of the colon as the indication for colectomy) [14]. For average-risk patients, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICER) for no surveillance versus surveillance every 1, 3 and 5 years was $69,040, $41,325 and $36,516 per life year gained, respectively. For above-average-risk population the ICER for no surveillance versus surveillance every 1, 3 and 5 years was $10,071, $5,910 and $4,911 per life year gained, respectively. For the high-risk population, the ICER for no surveillance versus surveillance every 1, 3 and, 5 years was $3,456, $2,119 and $2,036 per life year gained, respectively. For the high-risk patients, the added life years gained between surveillance yearly compared to every 3 years was 1.1 years and the ICER of surveillance every year compared to every 3 years was $5,279. Sensitivity analysis revealed robust results [14].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree