Fig. 44.1

Schematic representation of the correct TME dissection versus an incorrect dissection. The dissection should proceed between the mesorectal fascia and the pelvic wall fascia to ensure a “complete” TME

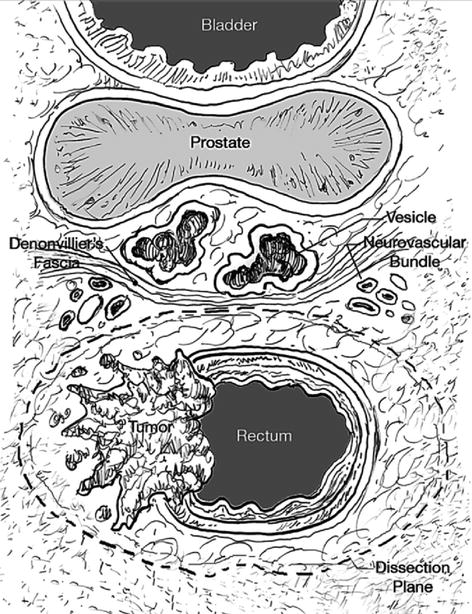

Fig. 44.2

Transverse diagram of the structures of the mid rectum. The proper dissection proceeds just outside the mesorectal fat and fascia but with sparing of the neurovascular bundle and hypogastric plexus that is located anterolaterally along the pelvic sidewall. One or both layers of Denonvilliers’ fascia should be included in males and the equivalent fascial dissection along the back of the vagina in females

Distal Margins and Radial Margins

The extent of resection margins in rectal cancer remains controversial. Although the first line of rectal cancer spread is upward along the lymphatic course, tumors below the peritoneal reflection may also spread distally by intramural or extramural lymphatic and vascular routes. When distal intramural spread occurs, it is usually within 2.0 cm of the tumor, unless the lesion is poorly differentiated or widely metastatic.

Williams et al. in 1983 reported distal intramural spread in 12 of 50 resected rectal cancer surgical patients. It was observed that 10 of the 12 had Stage III lesions. Only 6 % had distal intramural spread greater than 2 cm. They concluded a “wet” margin of 2.5 cm was adequate in 94 % of the patients.

They noted that only five patients (10 %) had tumors beyond a 1.5-cm margin, and all five of these patients had poorly differentiated, node-positive cancers. Also, the mortality in this group of patients was attributable to distant metastases, not local recurrence.

Pollett and Nicholls observed no difference in local recurrence rates whether distal margins of <2 cm, 2–5 cm, or >5 cm were achieved.

Finally, in two early studies from the British literature, surgical pathology of rectal and rectosigmoid cancer demonstrated the clinical biology of extramural lymphatic spread. In the series by Goligher et al. from 1951, only 6.5 % of patients had metastatic glands below the primary tumor, whereas 93.5 % had no retrograde spread. Approximately two-thirds of patients with retrograde spread had metastasis limited to within 6 mm of the distal tumor edge, and only 2 % had metastasis beyond 2 cm. Dukes published similar results in a study of more than 1,500 patients who had undergone APR.

Further data from a randomized, prospective trial conducted by the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project demonstrated no significant differences in survival or local recurrence when comparing distal rectal margins of <2 cm, 2–2.9 cm, and >3 cm. As a result, a 2-cm distal margin has become acceptable for resection of rectal carcinoma.

Based upon these extensive data, a 2-cm distal margin is justifiable over a 5-cm distal margin. Even smaller distal margins may be acceptable in certain patients for whom there is no other option for sphincter preservation. In these cases, a frozen section analysis of the distal margin can be performed to confirm a cancer-free margin.

The discussion concerning the distal margin should not be confused with the issues regarding a TME and the radial margin. It is now clear that the status of the radial margin is perhaps the most critical in local control and determining prognosis.

Quirke et al. in 1986 demonstrated tumor spread to the radial margins of 14 of 52 rectal cancers on whole mount specimens (27 %). Twelve of these 14 patients subsequently developed local recurrence, suggesting that local recurrence is largely a result of radial spread.

Lateral Lymph Node Dissection

A complete clearance of lateral lymph nodes or extended lateral lymph node dissection (ELD) for low-lying rectal cancers with suspected or high risk for lateral lymph node metastasis has been a routine practice in Japan. The practice is based on the existence of lateral lymphatic drainage of the rectum, which TME does not encompass. Lateral lymphatic flow passes from the lower rectum and through lateral ligaments beyond mesorectum and ascends along internal iliac arteries and inside the obturator spaces. A study from Japan showed that the incidence of lateral lymph node involvement for low-lying rectal cancer is 16.4 %. A recent study from the Netherlands compared the treatment of rectal cancer between Japan and the Netherlands and showed 5-year local recurrence rates of 6.9 % for the Japanese ELD group, 5.8 % in the Dutch RT + TME group, and 12.1 % in the Dutch TME group.

ELD is associated with a much higher rate of urinary and sexual dysfunctions as compared to standard TME.

ELD is a controversial topic, and more studies need to be done on its effectiveness and the benefits versus increased morbidity before it can be recommended as a standard of care. However, in some patients where there are palpable nodes along the pelvic sidewall and along the iliacs, a patient may benefit from this extended dissection.

Selection of Appropriate Therapy for Rectal Cancer

Three major curative options: local excision, sphincter-saving abdominal surgery, and APR.

Clinical features may also have an impact on therapeutic decisions. Patients with physical handicaps may have significant difficulty in managing a stoma. Body habitus and patient gender influence the surgeon’s ability to perform a sphincter-saving operation because of pelvic anatomy. A history of pelvic irradiation or nonrectal pelvic malignancy can make a rectal resection and sphincter preservation more difficult.

In summary, each patient with rectal cancer should be individually evaluated, and a technical plan for their resection is customized to their stage, gender, age, and body habitus (Fig. 44.3). With these issues in mind, the technical choices for a radical resection are discussed below. In all of these resections, a TME should be performed. Local treatments are discussed in detail in Chap. 43.

Fig. 44.3

Treatment options for rectal cancer depending on stage and location. Stage I (T1N0, T2N0 – the cancer is confined to the rectal wall, and no nodes are involved). Distal rectal cancers: T1 (invasion into the submucosa only): Local excision; Radical resection, often an APR; Adjuvant therapy is usually not recommended. Distal rectal cancers: T2 (invasion into the muscularis propria): Local excision with preoperative or postoperative adjuvant therapy; Radical resection without adjuvant therapy, often an APR. Mid rectal cancer: T1: TEM (transanal endoscopic microsurgery); Radical resection, usually an LAR with low anastomosis. A temporary proximal diverting ostomy is often required; Adjuvant therapy is usually not recommended. Mid rectal cancer: T2: TEM with either preoperative or postoperative adjuvant therapy; Radical resection similar to a T1 cancer; Adjuvant therapy is not recommended if a radical resection is performed but is recommended before or after a TEM resection. Upper rectal cancers: T1 and T2: LAR; TEM? Stage II and Stage III cancers [Stage II cancers have invasion into the mesorectal fat (T3) but no involved mesorectal lymph nodes. Stage III cancers are any rectal cancer (T1, T2, or T3) but with involved lymph nodes.] Distal rectal cancers: Preoperative adjuvant therapy is most often recommended followed by a radical resection, usually an APR; If preoperative imaging does not clearly define the stage of the cancer, resection can be done first followed by postoperative adjuvant therapy. Mid rectal cancers: Same as above for distal rectal cancers except an LAR is usually performed instead of an APR. Upper rectal cancers: LAR, with either preoperative or postoperative adjuvant therapy. Stage IV cancers: Treatment for any cancer is dependent on the extent of metastasis. With better surgical and medical treatments for metastatic disease, locoregional control of the primary should be aggressive and similar to the above recommendations except in the most advanced cases. Key: LE local excision, short XRT short-course radiation therapy given two times a day for 5 days in larger fractions, ChXRT long-course therapy given in 30 smaller fractions over 6 weeks in combination with chemotherapy

Techniques of Rectal Excision

Abdominoperineal Resection

The APR was the first radical resection described by Miles in 1908 (reprinted in 1971). Miles set out several principles to be achieved with any radical resection. These principles included:

Removal of the whole pelvic mesocolon

Removal of the “zone of upward spread” in the rectal mesentery

Wide perineal dissection

An abdominal anus

Removal of the lymph nodes along the iliacs.

Four of five of these principles are the anchor of our technique even today (the dissection along the iliacs is not routinely done).

Candidates for an APR include patients whose tumors are either into the anal sphincter or are so close to the anal sphincter that a safe distal margin cannot be obtained. Also, there is a small subset of patients with mid rectal tumors but with poor continence who may benefit from an APR, even though they are technically sphincter-preservation candidates.

There are two approaches to APR with TME, excision of the sphincter and levators and creation of a permanent colostomy. Traditionally, the APR has been done in lithotomy position.

Recently, there have been reports of oncologic superiority of cylindrical APR that is performed in prone position or robotically. The cylindrical approach closely resembles the original Miles APR. A recent paper by West et al. showed that cylindrical APR results in more cylindrical specimen (hence the name) and removes more tissue in the distal rectum and leads to lower radial margin involvement (14.8 versus 40.6 %) and intraoperative rectal perforations (3.7 versus 22.8 %).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree