Chapter 51 Surgical Techniques for Management of Anomalies of the Müllerian Ducts and External Genitalia

INTRODUCTION

Malformations of the müllerian ducts and the external genitalia can have significant impact on both reproductive potential and sexual function. When a patient presents with such an abnormality, it is important to put significant thought and time into determining the correct diagnosis and subsequent treatment. This is particularly true for surgical management of external genitalia anomalies, where consequences, in terms of gender assignment and later sexual function, remain largely uncertain.

This chapter begins with a review of the diagnostic and presurgical evaluation of these anomalies. The majority of the chapter deals with basic principles of surgical techniques used to correct these anomalies. The pathophysiology of genital anomalies is reviewed in Chapter 12.

CLASSIFICATION

The classification of müllerian anomalies helps with both diagnosis and the comparison of outcomes after various modes of management. However, there is no single classification that encompasses all anomalies that have been reported in the literature.1–3

On the basis of pathophysiology, müllerian anomalies can be broadly classified into problems according to the developmental mechanism whose failure gave rise to the malformation. Anomalies can usually be classified as being related to (1) agenesis, (2) vertical fusion defects, or (3) lateral fusion defects.4

The most accepted classification of uterine anomalies, published by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), places uterine anomalies into distinct groups based on anatomic configuration (Table 51-1).5 Because vaginal anomalies are not included in this classification, they must be described along with the uterine anomaly. This classification does not give insight into pathophysiology, but it is an effective way to communicate observations for purposes of treatment and prognosis.

Table 51-1 ASRM Classification of Müllerian Anomalies

MÜLLERIAN AGENESIS

Clinical Presentation

Müllerian agenesis (i.e., Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome) was first described in 1829. Its incidence is reported to be 1 in every 5000 newborn females.6 Because the vagina and associated uterine structures do not develop with this disorder, it is a ASRM Class IA müllerian anomaly. Patients typically present during their adolescent years with complaint of primary amenorrhea. As a cause of primary amenorrhea, müllerian agenesis is second only to gonadal dysgenesis.7

Because these patients have a 46,XX karyotype, normal ovaries will be present in the pelvis. Ovulation can be documented as a shift in basal body temperature. These patients’ hormonal levels are normal, and their cycle length based on hormonal studies varies from 30 to 34 days.8 In addition they may experience the monthly pain (mittelschmertz) that is indicative of ovulation.

Associated Anomalies

Some but not all anomalies described can be extrapolated from the embryology.9–12 Hearing difficulties have been reported in patients with müllerian agenesis.10,11 A higher rate of auditory defects have been noted in general in patients with müllerian anomalies compared to those with normal müllerian structures.12

Müllerian agenesis is associated with renal and skeletal system anomalies. Renal abnormalities are noted in 40% of these patients. These include complete agenesis of a kidney, malposition of a kidney, and changes in renal structure.13 Skeletal abnormalities are noted in 12% of patients and include primarily spine defects followed by limb and rib defects.14 Patients with müllerian agenesis should be actively assessed for these associated anomalies.

Etiology

The etiology of müllerian agenesis remains unknown. It appears to be influenced by multifactorial inheritance, and rare familial cases have been reported. It does not appear to be transmitted in an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, because none of the female offspring of women with müllerian agenesis (born via in vitro fertilization [IVF] and surrogacy) have shown evidence of vaginal agenesis.9

CREATION OF A NEOVAGINA

The first goal of treatment of müllerian agenesis is creation of a functional vagina to allow intercourse. Frank first proposed vaginal dilation with use of a dilator as a means of creating a neovagina in 1938.15 However, the surgical techniques of vaginoplasty remained the preferred methods for many years. The success of any technique depends in large part on the emotional maturity of the patient. Pretreatment counseling and continued support during treatment is important.

Vaginal Dilation

The simplicity and ease of vaginal dilation and its significantly lower complication rate than surgical techniques dictates its use as initial form of therapy for most patients with müllerian agenesis. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recently released a committee opinion that recommends nonsurgical management of müllerian agenesis as the first mode of treatment.16

Frank’s technique of dilation involves actively placing pressure with the dilators against the vaginal dimple (Fig. 51-1). The patient is not only in an awkward position, but the hand applying the pressure can also become tired. In 1981, Ingram proposed the concept of passive dilation, where pressure is placed on the dilator by sitting on a bicycle seat.17

Roberts reported a success rate of 92% in women who dilated the vagina via the Ingram technique for 20 minutes three times a day.18 The average time to creation of a functional vagina was 11 months. This series demonstrated that an initial dimple less than 0.5cm was all that was necessary to achieve adequate dilation. Interestingly, failure of this technique was not related to length of vaginal dimple but rather was more closely associated with the patient’s youth. Failure of this technique was more common in patients younger than age 18.

Procedure

When the patient expresses a desire to proceed with therapy, she is shown the exact location of her vaginal dimple. The axis of dilator placement is also demonstrated (Fig. 51-2). The process is initiated by placement of the smallest dilator against the dimple. Pressure is kept on the distal aspect of the dilator by sitting on a stool while leaning slightly forward. When the dilator fits comfortably she moves to the next size dilator. The patient is instructed to use this technique a minimum of 20 minutes a day, two to three times a day. In motivated patients, a functional vagina can be created in as short as 12 weeks.

Counseling and psychological support is integral to successful treatment.19–21 Patients are requested to return to the office frequently to monitor their progress, provide guidance, and have an opportunity to answer questions. Intercourse may be attempted when the largest dilator fits comfortably.

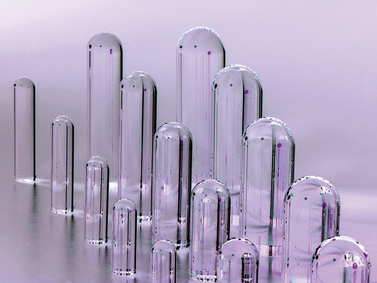

Multiple types of graduated dilators, made of various materials, are present on the market. None have been found superior to the others. Patients may stop and reinitiate the dilation at any time without any negative long-term sequelae. Although most patients appear interested in initiating this therapy the summer before college when they are mature enough and motivated to create the vagina, the timing of therapy is purely dependent on the patient’s desires. The median age of starting treatment is 17 years.22 For appropriately selected motivated patients, the reported success rates are as high as 90%.23

Vecchietti Procedure

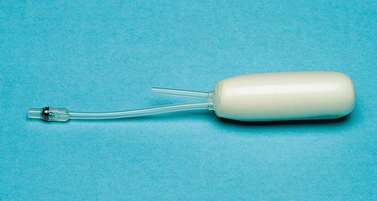

Giuseppe Vecchietti described this method of creating a neovagina in 1965.24 Similar to vaginal dilation, this method avoids the use of a graft. The Vecchietti procedure is a one-step procedure in which a neovagina is created in 7 days by continuous pressure on the vaginal dimple using an acrylic olive connected by retroperitoneal sutures to a spring-tension device on the lower abdomen. Although the original description of the Vecchietti procedure utilized laparotomy, this technique is currently performed laparoscopically.25,26

Procedure

The next step is to use a curved blunt ligature carrier to burrow retroperitoneally from a lateral suprapubic laparoscopic port site to the peritoneal fold between the bladder and the uterine rudiment. One end of the olive suture is placed through the eye of this curved ligature carrier and pulled retroperitoneally back through the abdominal wall port site incision. This procedure is repeated on the opposite side with the other end of the suture. After the laparoscope is removed and the abdominal wall incisions are closed, the ends of the suture are attached to a suprapubic Vecchietti spring-traction device located externally on the abdomen.25

Vecchietti reported a series of more than 500 patients with a success rate of 100% and only nine complications, including one bladder and one rectal fistula.27 Several smaller studies have subsequently been reported by other surgeons with similar outcomes.28,29 A 3-year follow-up study assessed the functional and psychological outcome in five patients.30 All five subjects reported having a functioning vagina allowing satisfactory intercourse and improvement in general well-being.

Vaginoplasty Techniques

The traditional surgical management of vaginal agenesis is to create a vaginal space followed by placement of a lining to prevent stenosis. Multiple tissues and at least one manmade material have been used to line this cavity with varying degrees of success in preventing subsequent stenosis of the neovagina (Table 51-2).

Table 51-2 Surgical Methods of Creating a Neovagina

McIndoe Procedure

The skin graft is placed through a 1:5 ratio skin mesher. The purpose of meshing the skin is not to stretch it but rather to allow escape of any underlying blood clots or serous fluids. This skin graft is sutured around the mold with 4-0 absorbable suture (Fig. 51-3). The mold is covered completely, because any uncovered sites, whether due to lack of enough tissue or a gaping hole in the line of suture, tend to result in the formation of granulation tissue. Thus great care must be taken to obtain a sufficient amount of graft for this procedure.

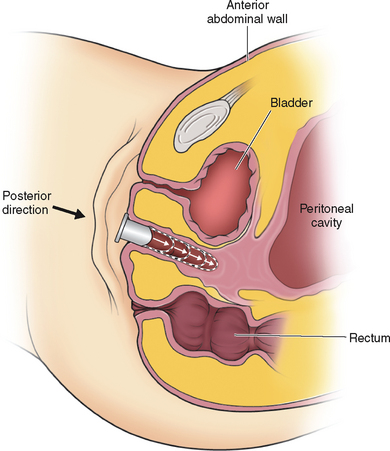

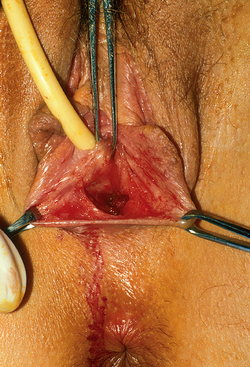

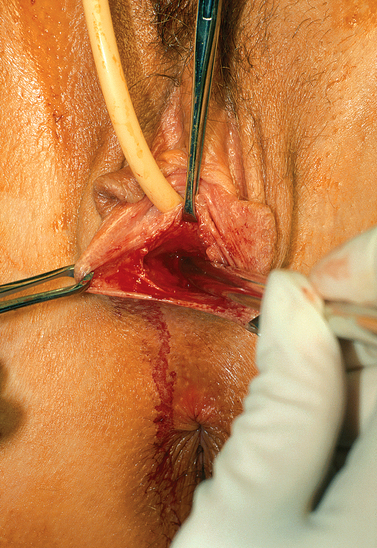

The patient is placed in the dorsolithotomy position. A transverse incision is made in the vaginal vestibule, between the rectum and urethral openings (Fig. 51-4). In a patient who has not had prior surgery or radiation in the area, areolar tissue is now encountered. This tissue is easily dissected with either fingers or a Hagar dilator on either side of a median raphe (Fig. 51-5). The dissection is continued for at least the length of the mold without entering the peritoneal cavity. By cutting the median raphe, the two channels are then connected. If the dissection is performed in this manner, minimal bleeding is encountered. Any bleeding sites must be controlled meticulously to avoid lifting of the graft from the newly created vaginal wall and subsequent nonadherence and necrosis.

Figure 51-4 The initial transverse cut was made on the fibrous tissue and an initial space developed.

Figure 51-5 Placement of Hagar dilator to create space for the graft. The direction of the Hagar dilators is posterior.

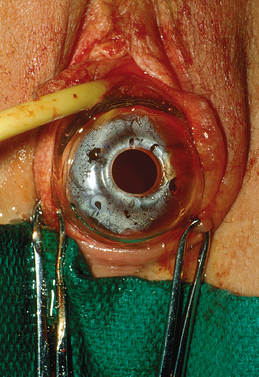

After creation of the vaginal space, the mold covered with the skin graft is placed inside the cavity (Fig. 51-6). At the introitus, the skin graft is attached with several separate 3-0 absorbable stitches. To hold the mold in place, several loose nonreactive sutures such as 2-0 silk are used to approximate the labia minor in the midline.

Difficulty in dissecting the neovagina and increased probability of bleeding and fistula formation is encountered in the patient with a prior surgical procedure. Other problems that may be encountered include narrow subpubic arch, strong levators, shorter perineum, prior hymenectomy, and congenitally deep cul-de-sac.31

Because of concern regarding tissue necrosis from mold pressure and subsequent fistula formation, both rigid and soft molds have been used for this procedure (Figs. 51-7 and 51-8). Theoretically, soft molds decrease the risk of fistula formation that can result from avascular necrosis. A soft mold can be created by covering a foam rubber block with a condom.32 The foam is able to expand and fit the neovaginal space, thereby providing equal pressure throughout the canal. However, a report on the use of a rigid mold on 201 patients who underwent the McIndoe operation demonstrated a fistula formation rate of less than 1%.33 There is no study comparing the outcomes of soft versus rigid molds in this operation. Typically a rigid mold is used initially, but the patient is sent home with a soft mold in place.

An 80% success rate has been reported with this procedure.34 Because success rates are highest in those patients that have not undergone prior vaginoplasty, patients must be counseled extensively before surgery regarding the need for prolonged use of the mold. Indeed, part of the presurgical assessment involves determination of patient maturity and motivation concerning the use of dilators. Lack of compliance with postoperative use of dilators will lead to contracture and diminishment of vaginal length.

Surgical complications include postoperative infection and hemorrhage, failure of graft and formation of granulation tissue, and fistula formation. In general the incidence of complications are low: a rectal perforation rate of 1%, graft infection in 4%, and graft site infection of 5.5%.33 In a review of 50 patients, 2 rectovaginal fistulas and 1 graft failure were reported.31 Five patients required an additional operative procedure. Eighty-five percent of these patients considered their surgery to be a success.

Long-term data on the McIndoe procedure, although limited, consistently indicate an improvement in quality of life. In a series of 44 patients who underwent a surgical procedure to create the vagina, 82% achieved a functional satisfactory postoperative result.35 Vaginal length varied from 3.5 to 15cm. In another long-term study of women who underwent a McIndoe procedure, 79% of the patients reported improved quality of life, 91% remained sexually active, and 75% regularly achieved orgasm.36

The newly created vagina must be inspected at the time of the yearly pelvic examination and regular pap tests. Hair growth has been reported to be a problem with some skin grafts. Transformation to squamous cell carcinoma from skin graft has been described.37,38

Peritoneal Graft: Davydov Procedure

Use of the peritoneum to line the newly created vaginal space was popularized by Davydov, a Russian gynecologist, and first described by Rothman in the United States in 1972.39–41 In his original description, a laparotomy is performed after creation of the vaginal space, as described with the McIndoe operation.

A cut is made on the peritoneum overlying the new vagina. Long sutures are applied to the anterior posterior and lateral sides of this peritoneum. The sutures are then pulled down through the vaginal space, thus pulling the peritoneum to the introitus. The edge of the peritoneum is then stitched to the mucosa of the introitus. Closing the peritoneum on the abdominal side then forms the top of the vagina. Several investigators have also described the laparoscopic modification of this procedure.42–44

Adhesion Barrier Lining

Jackson first described the use of an adhesion barrier to line the neovagina in 1994.45 Oxidized regenerated cellulose (Interceed; Johnson and Johnson Patient Care Inc, New Brunswick, N.J.) forms a gelatinous barrier on raw surfaces and thus prevents adhesion formation. After creation of the vaginal space, sheets of clothlike oxidized regenerated cellulose are wrapped around the mold and placed in the vagina in a manner similar to the McIndoe. The neovaginal space must be free of any bleeding. Epithelialization is noted to occur within 3 to 6 months. Small areas of granulation tissue may be seen at the apex of the vagina and resolve after application of silver nitrate. Average vaginal depth ranges from 6 to 12cm. Continuous use of the mold is encouraged until complete epithelilization has occurred.

A case series assessed the outcome of this technique on 10 patients with vaginal agenesis.46 Complete squamous epithelialization was noted within 1 to 4 months. When compared to a normal vagina, fern formation was noted and the vaginal pH was always acidic. However, none of the women complained of vaginal dryness or foul-smelling discharge. Patients who were sexually active did not report any problems.

Amnion Lining

Amnion has also been used to line the neovagina cavity.47 Advantages include lack of a graft site, potential antibacterial effect, and lack of expression of histocompatibility antigens.48,49 Eight to 10 weeks after placement of amnion into the vaginal canal, the resulting epithelium was found to be “identical” to normal vaginal epithelium.50 However, concern about transmission of an infection with use of amnion has limited its use in the United States.

Muscle and Skin Flap

The use of gracilis myocutaneous flaps and rectus abdominis myocutaneous flaps for vaginal reconstruction has been reported.51,52 This approach has been associated with a conspicuous scar and a higher failure rate. Wee and Joseph in Singapore designed flaps that maintained good blood supply and innervation.53 Known as a pudendal–thigh flap vaginoplasty, this technique has been particularly successful in patients with vulvar anomalies.54 In one study of patients with müllerian agenesis, 100% success in creating a functional vagina was reported.55

The patient’s own labia majora and labia minora have also been used to create a vagina.56 Tissue expansion has also been advocated to create labiovaginal flaps, which are then used to line the neovagina.57,58 Other modifications of this procedure have been reported.59,60

Bowel Vaginoplasty

Continuous use of dilators is not considered necessary, although constriction has been noted when ilium has been used. Success rates of up to 90% have been reported. Reported complications include profuse vaginal discharge, prolapse, introital stenosis, bowel obstruction, and colitis.61,62 Finally there is a report of a mucinous adenocarcinoma arising in a neovagina lined with the sigmoid colon.63

A laparoscopic modification of this procedure has also been described.64,65 Given the increased complication rates, it seems appropriate to reserve this treatment modality for complex situations where a prior vaginoplasty technique has failed or when there are multiple urogenital malformations.

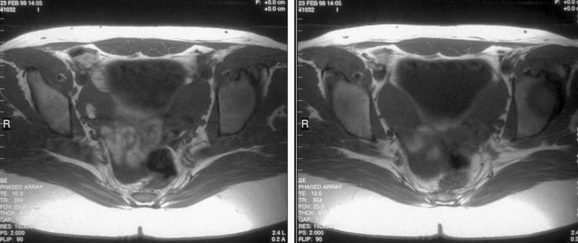

OBSTRUCTED RUDIMENTARY UTERINE BULBS

Patients with müllerian agenesis commonly have müllerian remnants noted on MRI or during a laparoscopy. The MRI has the added value of determining if any endometrial tissue exists within these remnants (Figs. 51-9 and 51-10). Patients with functional endometrial tissue may present after many asymptomatic years with cyclic pelvic pain secondary to monthly endometrial shedding, and development of endometriosis has been reported in these patients. Symptomatic müllerian bulbs should be removed either via laparotomy or laparoscopy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree