Chapter 28 Surgical Sterilization

HISTORY

In the 1970s tubal sterilization became widespread due to the introduction of minilaparotomy and laparoscopy as methods. Anderson1 is credited with performing the first laparoscopic electrocoagulation procedure in the United States in 1937. Steptoe2 in 1967 reported the first large series of laparoscopic sterilizations, and Wheeless3 in 1973 reported the first single-puncture laparoscopic technique. These procedures allowed for interval surgery, surgery without hospital stay, reduced recovery time, less morbidity, and better cosmetic result.4 Sterilization is now the most commonly used method of family planning in the world.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

Tubal sterilization should be available to any woman who desires permanent sterilization, assuming that she has proper informed consent (Table 28-1) and adequate knowledge regarding the procedure. The procedure should be considered purely elective. There are virtually no absolute contraindications to tubal sterilization except for gynecologic malignancy or gynecologic disease that requires hysterectomy or bilateral oophorectomy.

Table 28-1 Elements of Informed Consent for Sterilization

| Review of alternative methods of permanent sterilization (e.g., vasectomy) |

| Indication that the procedure is considered permanent |

| Review of failure rate of procedure |

| Description of the planned operative technique |

| Discussion of potential surgical risks |

Informed Consent

Various materials are available to assist the physician in counseling the patient. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) distributes a pamphlet that discusses different techniques of sterilization as well as alternative methods for contraception. For couples desiring permanent sterilization, vasectomy should always be discussed because vasectomy is associated with fewer complications than tubal sterilization. When counseling the patient on the benefits of sterilization, it is important to include that all methods are extremely effective, are permanent, and have a low failure rate.5 Risks of the female sterilization procedure include risk of anesthesia, operative surgical risks, and the 1% to 3% risk of failure with an increased risk of ectopic pregnancy. It should be remembered that patients whose sterilization will be federally funded must sign a special consent document and must be at least 21 years old.

Sterilization Regret

Anywhere from 3% to 25% of women have regret about sterilization, and 1% to 2% of these patients actually seek tubal reversal. Some reasons for regret (Table 28-2) include change in marital status, death of a child, and wanting another child after other children have gotten older. Studies have shown that there is an increased risk of regret with change in marital status, age less than 30 at the time of sterilization, psychiatric history, postpartum sterilization, poor outcome with previous delivery, and ongoing marital, financial, health, or personal problems at the time of sterilization.5

Table 28-2 Factors That Have and Have Not Been Associated with Regret After Sterilization

| Factors Associated with Regret | Factors Not Associated with Regret |

|---|---|

| Marital status change | Religion |

| Family stress (e.g., death of a child) | Socioeconomic level |

| Desire for additional children as the “baby” grows up | Education level |

| Post-tubal ligation syndrome symptoms | Low parity |

| Postpartum procedure | Decision made with husband’s approval |

| Sterilization before age 30 | Interval procedure |

TIMING

Postpartum Sterilization

Sterilization after delivery, during the patient’s postpartum hospital stay, is a convenient, effective, and efficient way to prevent future pregnancy. In the immediate postpartum period the uterus is enlarged to the level of the umbilicus, making it convenient to perform sterilization with a small 1- to 2-cm infraumbilical incision. Any of several techniques could be used. The longest period that the patient may wait before undergoing sterilization is controversial. In some circumstances, a delay of 12 to 24 hours may be needed to assess the infant’s condition, or delays secondary to staffing patterns or availability of anesthesia may be encountered. Studies done show no increased risk of morbidity if the sterilization is delayed for the first postpartum day.6,7 If it is not feasible during this time period to perform the sterilization, the patient should probably wait at least 6 weeks so that the uterine architecture will be back to normal. Before this time, the uterus may be enlarged, making laparoscopy more difficult, and there may be an increased risk of infection during the postpartum period. The patient who has a postpartum endometritis or has had premature rupture of the membranes, intrapartum fever, or manual placental removal is probably at risk of a postsurgical infection. Therefore, it may be prudent for this patient to wait and undergo interval sterilization.

Interval Sterilization

Interval sterilization after the immediate postpartum period should be delayed for 6 or 8 weeks. Most of these procedures are performed by laparoscopy and can be done using local, conduction, or general anesthesia. Performance of the procedure during the menstrual or proliferative phase of the cycle reduces the chance of pregnancy at the time of the procedure. However, if this is not practical, a sensitive urine or serum pregnancy test can be done on the day the procedure is performed. This too has been shown to decrease the risk of luteal phase pregnancy.8 Finally, sterilization can be performed in conjunction with other surgical procedures, such as cholecystectomy or plastic surgical procedures.

STERILIZATION METHODS

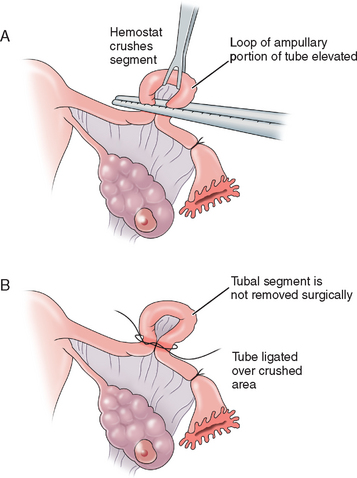

Madlener Technique

The Madlener technique involves forming a loop of tube, of which a portion is crushed at the base of the loop and ligated with a nonabsorbable suture. Occlusion but not division of the lumen is achieved (Fig. 28-1). The end result is similar to the laparoscopic placement of a Silastic band for occlusion, as described in the section on the Falope ring in this chapter. Failures are often attributed to fistula formation at the ligature site. This technique is generally of historic interest only.

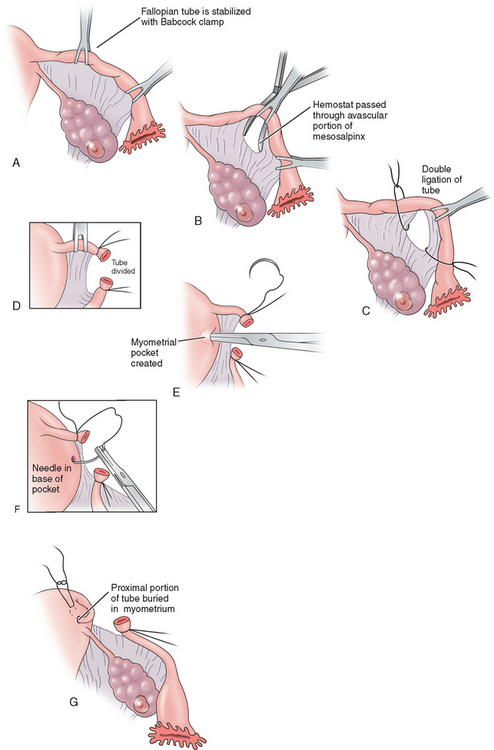

Irving Procedure

The Irving procedure was introduced as a technique for ligation and division of the oviduct at the time of cesarean section. At the ampullary–isthmic junction, the proximal stump is buried within the myometrium and the distal stump is buried between the leaves of the broad ligament (Fig. 28-2). As the uterus undergoes involution postpartum, the buried proximal and distal ends of the tubes become compressed and eventually obliterated. This procedure takes longer and there is often more blood loss; however, the chances of tubal recanalization or pregnancy in the proximal stump are remote.

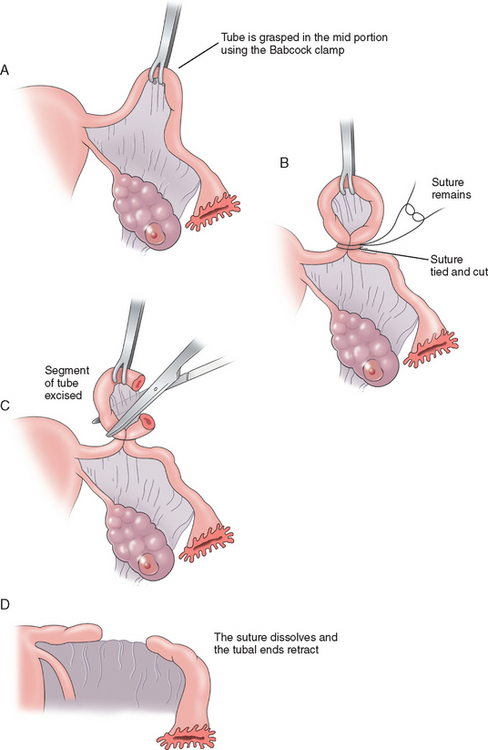

Pomeroy Method

The Pomeroy method (Fig. 28-3) or its modifications are probably the most commonly used sterilization procedures today. A knuckle of tube is grasped at the midportion using a Babcock clamp. This segment of tube, approximately 2cm in length, is then ligated at the base with an absorbable suture, preferably plain gut. This segment of tube is then excised and sent to the pathology laboratory for confirmation. The use of absorbable sutures allows the proximal and distal segments of the tube to separate, thus decreasing the risk of recanalization of the tube. The advantages to the Pomeroy method are that it is easy and quick to perform and highly effective. Its acceptance for both postpartum and interval sterilization is quite high.

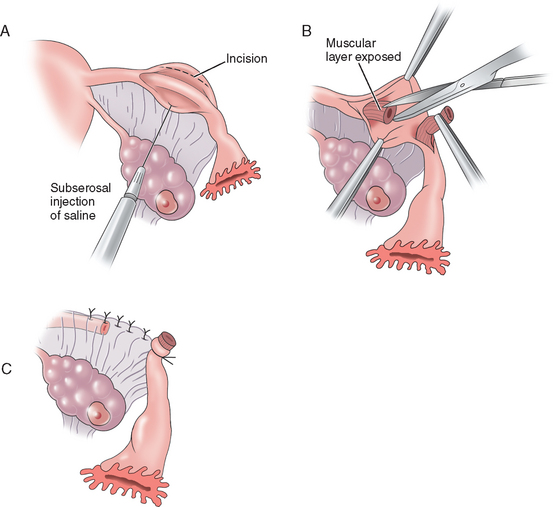

Uchida Technique

The Uchida technique is one of the more complex methods of tubal sterilization. It involves injection of a saline–epinephrine solution to the subserosal aspect of the tube, separating the muscular portion of the tube from the serosa. The serosa is then dissected off the muscular tube and a 5-cm segment of tube is excised while the proximal end is ligated and allowed to retract into the mesosalpinx. The mesosalpinx is then closed and a pursestring stitch is placed around the distal end to secure its position open to the abdomen (Fig. 28-4). A fimbriectomy may be added to this procedure to enhance effectiveness and prevent reanastomosis. The Uchida technique is more complicated than the other procedures but has been associated with very few failures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree