■ Operative hemorrhoidectomy classically describes the removal of both internal (proximal to the dentate line) and external hemorrhoidal tissue (distal to the dentate line). However, new advances and procedures such as Doppler-guided hemorrhoidal ligation or transanal hemorrhoidal dearterialization (THD) can be performed with less pain and enhanced recovery times, as there is no cutting of the anoderm, and the operative field is proximal to the dentate line.

■ Excisional hemorrhoidectomy remains the gold standard operation to which all treatments are compared, as its safety as well as durability has withstood the test of time. However, it remains a painful operation, and other measures may be weighed against a possibly higher recurrence rate with substantially reduced postoperative pain.

■ Furthermore, with the rising population of patients on full anticoagulation because of the growing ability to treat severe cardiovascular diseases as chronic illnesses, older techniques such as sclerosant therapy become handy operative tools for the acutely bleeding patient, in whom further suturing runs the risk of further bleeding.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

■ Anal cancer, particularly melanoma

■ Anorectal varices

■ Perianal cyst disease

■ Anal condyloma

■ Pedunculated polyps

■ Protruding anal papillae

■ Anal skin tags, particularly sentinel tags associated with anal fissures

■ Crohn’s disease

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ In order to treat hemorrhoids effectively, the other items in the differential diagnosis must be ruled out. Additionally, when considering surgical options, the pain of a traditional hemorrhoidectomy may be avoided by other methods that treat internal hemorrhoidal disease. Accurate diagnosis and determination of internal versus external hemorrhoidal disease must be ascertained to decide on the best operation for the patient.

■ A thorough history and physical should be performed prior to treatment, including a detailed past medical history, present medications and allergies, and particularly conditions such as cirrhosis or previous treatment with radiation.

■ Toileting behaviors, alteration in bowel function, and dietary changes must also be noted.

■ Conditions that impair venous drainage, push vascular cushions outward, behavioral/toileting abnormalities, and changes in sphincter function are all commonly believed to contribute toward worsening hemorrhoidal symptoms. Ultimately, venous congestion with subsequent hypertrophy of internal hemorrhoidal cushions leads to symptomatic hemorrhoids.

■ Prolonged straining increases abdominal pressure, which then impairs venous return, thus making the hemorrhoidal cushions unable to decompress transient congestion. Supportive tissues of the cushions then become gradually more and more attenuated, leading to prolapse of the cushion. Further prolapse then increases the possibility of trapping blood in the cushions with less abdominal pressure, thus causing progressive enlarging. Continued prolonged straining is an important preoperative history point because the behavior will need to be modified in the postoperative period to reduce pain and can worsen the efficacy of suture ligation operations.

■ Dietary factors and toileting behavior are also critical issues because they not only impair postoperative recovery, but they can also promote postsurgical anal fissures, compounding a difficult postoperative recovery.

■ Cirrhotic patients are at high risk for having anorectal varices, which are often mistaken for hemorrhoidal cushions. Elective hemorrhoidectomy for anorectal varices is fraught with excessive bleeding even to the point of hemodynamic instability in the stable patient once dissection for a misdiagnosis has started.

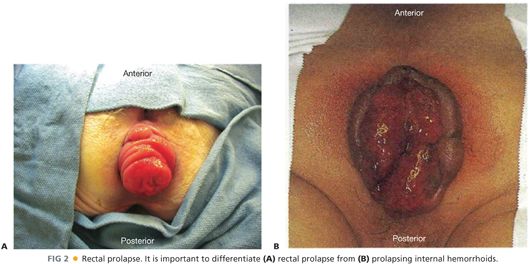

■ A complete rectal examination, which includes not just a digital rectal examination (DRE) but anoscopy and proctoscopy, is essential to the diagnosis. It is important to distinguish between rectal prolapse versus mucohemorrhoidal protrusion. Proctoscopy aids in the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease while allowing control of bleeding and biopsy. The number, location, grade designation, and relative size of hemorrhoids should be noted.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ Given a thorough physical examination, imaging or other diagnostic modalities are rarely indicated.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

■ Patients do not require bowel preparation for hemorrhoidectomy of any kind. Often, a simple enema before operation is sufficient for evacuation of the rectum. A rigid proctoscopy in the operating room before starting the procedure not only completes the preparation but also reviews the rectal mucosa for any signs of inflammation that may alter the surgical therapy or alert the surgeon to a heretofore unknown cause of straining.

■ The operation can be performed using a number of anesthetic choices and options, including: general anesthesia, local anesthesia with intravenous sedation, or even regional anesthesia.

■ Sequential compression devices (SCDs) are placed on the patient prior to the induction of general anesthesia.

■ When performing a THD procedure, a patient should be examined for the presence of external hemorrhoidal disease. The operating surgeon may feel that there is more benefit in performing a traditional hemorrhoidectomy when there is a substantial external component that could be worsened by an internal ligation procedure, which could cause subsequent levator spasm and tenesmus postoperatively.

■ When performing rubber band ligation of internal hemorrhoids, an office setting is most often well tolerated.

Positioning

■ Multiple positions are excellent for hemorrhoidectomy operations, including lateral Sims position (FIG 3), prone jackknife (FIG 4), or high lithotomy (FIG 5) using C-type “candy cane” footholders. Anesthesia concerns and surgical needs often are satisfied with the use of high lithotomy position. It is important to note that for prone jackknife, the folding mechanism of the operating table should be at the patient’s hip for maximal exposure, whereas in lithotomy the sacrum should be at the very edge of the bed. In smaller patients, a flattened and folded blanket or bedroll can be placed under the sacrum to provide some elevation of the perineum and forward projection.

■ Lithotomy patients using the C-type footholders often benefit from 45-degree angling of the footholder base toward the patient’s head, whereas the “C” should be orthogonal to the patient’s body. SCD/Venodyne boot cords can be tucked behind the adjustment flanges of the footholders. Such a position pushes the patient’s knees cephalad and feet medially.

■ For lithotomy patients undergoing either traditional hemorrhoidectomy or THD, an under-the-buttocks drape with a plastic drain pocket can be used to store the Doppler device or to clip instruments while suture ligating or sewing for ready access.

TECHNIQUES

TRADITIONAL EXCISIONAL HEMORRHOIDECTOMY (CLOSED FERGUSON TECHNIQUE)

Delineation of Hemorrhoidal Cushions and Skin Incisions

■ After performing a proper anoscopy using serial dilation of graded Hill-Ferguson retractors, a hemorrhoidal bundle can be readily exposed. Using a forceps or hemostatic clamp, the hemorrhoidal cushions can be gathered to facilitate the skin incision, which should spare the anoderm but include the hemorrhoidal bundle. This incision can be minimized by undermining directly underneath the hemorrhoidal bundle at the distal aspect and cutting inward directly into the anal canal to start the dissection (FIG 6).

Dissection of the Hemorrhoidal Vascular Tissue from the Internal Sphincter

■ After cutting directly under the hemorrhoid bundle distally and through the dermis, a Metzenbaum scissor carefully and sharply separates the vascular submucosal tissues from the adherent, often fibrous internal sphincter and intersphincteric groove (FIG 7).

■ A rule of thumb: Dissect the sphincter from the hemorrhoid rather than hemorrhoidal tissue from the sphincter.

Continued Skin Excision and Pedicle Isolation

■ As the surgeon dissects the sphincter off the hemorrhoid, a substantial “tunnel” is created; to save anoderm, the edges of the “tunnel” are simply cut directly toward the proximal aspect of the hemorrhoid, which can help make the operation progress by better easily delineating the hemorrhoidal bundle.

■

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree