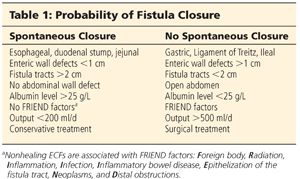

■ The probability of a spontaneous fistula closure is related to different factors summarized in Table 1. Three risk groups are then established in order to arrive at an objective determination of the degree of complexity of the fistula, the goals of the proposed treatment, and the predicted clinical course (Table 2).

■ Risk group I: good prognosis. This group includes patients with no debilitating disease who are in good general condition and no systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), with fistulas that have a good probability of closing spontaneously (diameter <5 mm, output <200 mL per day, single). Treatment is limited to support, and surgical closure is not considered initially.

■ Risk group II: intermediate prognosis. This group includes patients in acceptable general condition with no SIRS but with fistulas that have small probability of closing spontaneously (diameter >5 mm, output >500 mL per day, multiple fistulas). The treatment strategy is to initially stabilize the patient and subsequently perform early surgical closure.

■ Risk group III: poor prognosis. This group includes patients in poor condition who are malnourished, with debilitating diseases, who exhibit SIRS, and who have fistulas with small probability of closing spontaneously. The initial goal of treatment is to reduce fistula output, to achieve granulation and ostomization of the fistula, as well as to care for the open abdomen. The surgical closure is performed at a later stage (6 to 12 months), once the patient has recovered and both objective and subjective signs of recovery are satisfactory.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ The role of imaging is to define the anatomy, evaluate associated processes, and provide therapeutic alternatives for treatment.

■ Fistulograms are the most direct method of linking a cutaneous opening with the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. In the absence of sepsis, fistulograms may be the only imaging study needed. Two classes of contrast media are commonly used to evaluate the fistula tract, each with particular risks and benefits. Barium is a non–water-soluble media with high radiographic density, isotonic osmolarity, and an inert nature. Barium provides high-quality mucosal images, demonstrating areas of inflammation and the presence of fistula tracts with good accuracy. Unfortunately, if extravasated, barium causes significant peritoneal inflammation, including foreign body granulomas and peritoneal adhesions. Aqueous contrast agents, such as Gastrografin, are hyperosmolar and water-soluble. Water-soluble agents provide less mucosal detail; areas of inflammation, mucosal projections, and fistula tracts themselves may be missed. Gastrografin is rapidly absorbed within the peritoneal cavity if extravasated with minimal inflammation. To minimize risk and maximize benefits, water-soluble contrast material is often injected initially, followed by barium if no extravasation is seen and additional information is required.1,3,4

■ Small bowel follow-through (SBFT) studies provide a more global view of the intestinal tract. Multiple views are typically taken to optimize visualization. Ideally, barium is used for contrast as Gastrografin can be diluted as it moves distally through the GI tract. Fistulas with narrow lumen and distal fistulas may not be detected in SBFT studies. Previously opacified loops of bowel may complicate visualization of the fistula.

■ Ultrasound. Limitations of ultrasound include operator dependency, obesity, and difficulty of evaluating certain portions of the small bowel including duodenum and jejunum. Injection of hydrogen peroxide through the fistula orifice has been reported to increase the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound from 29% to 88% in ECF complicating Crohn’s disease.5

■ Computed tomography (CT) allows for the identification of extraluminal pathology, downstream disease, and inflammation (FIG 2).

■ Computed tomography enterography (CTE) uses “negative” contrast, which appears dark, allowing for distention of the bowel. With the concomitant administration of intravenous (IV) contrast that will delineate mucosa, negative contrast provides additional information concerning the mucosa surrounding a fistula tract.4

■ Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a promising adjunct to primary imaging modalities. Its use in ECF evaluation is beginning to be understood.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

■ The fundamental pillars for fistula management, initially described by Chapman,6 can be summarized by the SOWATS acronym: management of the Septic condition, Optimization of the nutritional status, surgical Wound care, fistula Anatomy, right Timing for surgery, and Surgical strategy.1 By adopting this strategy, they reduced ECF mortality from 40% down to 15%.

■ Sepsis: Associated infection is the primary cause of death in fistula patients. The initial management of a patient with an ECF, with or without associated infection, is fluid resuscitation to address dehydration and prevent renal failure. Blood transfusion has to be considered if required. There are two stages associated with the management of infection:

■ Early stage. When a fistula is suspected or diagnosed, the goal is to prevent or control generalized contamination of the abdominal cavity and subsequent peritonitis. Treatment at this stage is surgical or percutaneous invasive therapy together with the use of antibiotics.

■ Late stage. After the fistula tract has been established, the goal is to prevent or treat any secondary focus of infection, usually nosocomial (catheter-related sepsis, pneumonia, residual abscesses, etc.). Treatment at this stage is systemic or preventive.

■ Optimization of the nutritional status: Effective nutritional support is a priority. Although parenteral nutrition may be needed in some cases, recent publications favor enteral nutrition as a protective factor against associated infections. The enteral route must be considered when it is suspected that the fistula will not close spontaneously, when it is a low-output fistula, or when it is localized in the terminal ileum or the colon. The use of somatostatin and octreotide, which lower endocrine and exocrine secretion, reduces fistula output. The use of antiperistaltic agents such as loperamide and codeine is also helpful. The basic nutritional requirements consist of carbohydrates and fats 20 kcal/kg/day and proteins 0.8 g/kg/day. Caloric and protein requirements may increase to 30 kcal/kg/day and 1.5 to 2.5 g/kg/day, respectively, in patients with high-output fistulas.1,3

■ Surgical wound care: The goal of treatment is to avoid maceration and excoriation of the skin surrounding the ECF, one of the main causes of chronic pain in these patients. Multidisciplinary treatment is recommended preferably in a specialized wound clinic.

■ Fistula anatomy:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree