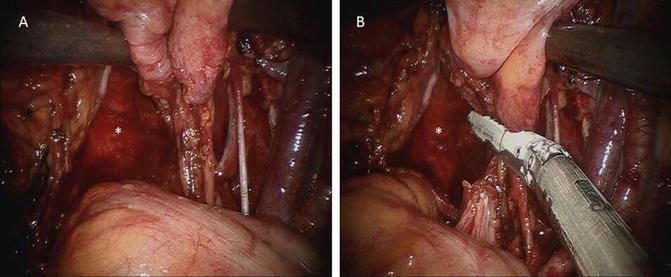

Fig. 16.1

Technique of ureteral clipping and division with pre-tied hem-o-lok clip

An additional technique we utilize to minimize ureteral ischemia, limitation of proximal mobilization to just above the common iliac vessels allows for mobilization of the ureter away from the working field during extended pelvic lymphadenectomy while maintaining perforating vessels to the ureter above the aortic bifurcation. Although tempting, additional proximal dissection is rarely needed to complete the urinary diversion, even if done through a limited incision during extracorporeal reconstruction.

While a small incision is possible, it is still important to make a large enough incision to accommodate construction of the urinary diversion. This allows for creation of the ureteroenteric anastomosis without additional ureteral tension aggravated by a small incision. We believe that the benefits of a robotic approach will not be undone through limited extension of this incision. Ultimately, performance of an incorporeal urinary diversion may help avoid tension-related insults to the ureteral blood supply.

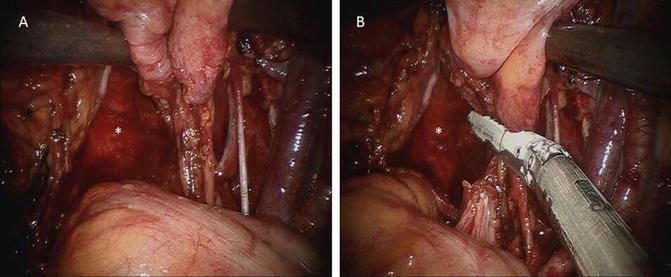

While ureteral complications are certainly troublesome, a rectal injury can be a disastrous complication which could result in a colostomy, rectal fistula, and even death if unrecognized. When performing the posterior dissection in male patients, particular attention should be paid to careful and thorough mobilization of the rectum to avoid injury during division of the vascular pedicles. Our preference for division of these pedicles is with use of a vascular stapler. The posterior dissection usually becomes more difficult as one progresses distally, and it should be kept in mind that the rectum lies in a more anterior location when approaching the prostatic apex. We recommend allotting adequate time to fully mobilize the distal aspect of the rectum away from the prostate in much the same fashion as one prepares for neurovascular bundle preservation during a robot assisted radical prostatectomy. Once this is accomplished, the surgeon will be left with a narrow column of vascular tissue from the superior vesical artery to the prostatic apex. This will allow safe application of the vascular stapler above all rectal tissue as shown in (Fig. 16.2). When employing the stapler, we recommend the larger, more blunt blade be positioned medially to avoid inadvertent placement of the sharper, thinner blade into the rectum; also helpful is upward (anterior) articulation of the stapler away from the rectum.

Fig. 16.2

(a) Isolation of right bladder pedicle after complete mobilization of the rectum. (b) Safe application of laparoscopic stapler above rectum (* = rectum)

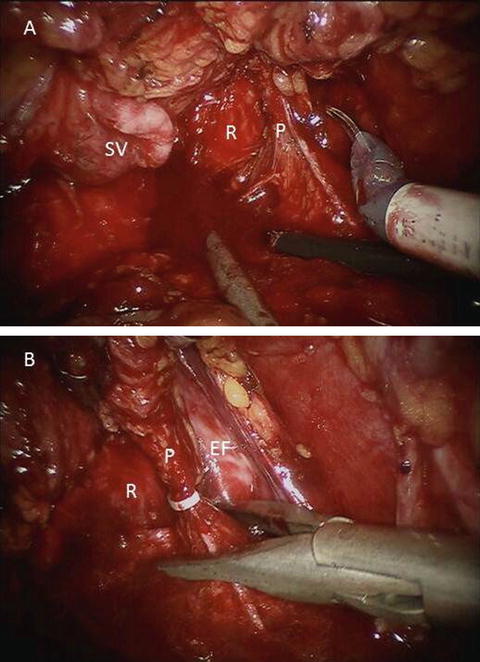

If the separation of the bladder/prostate and rectum is difficult, we would then recommend proceeding cautiously through isolation of individual pedicles as one progresses distally, using Hem-o-lok (weck) clips for vascular control (Fig. 16.3). Blunt and sharp dissection should be employed avoiding the use of excessive cautery to thereby avert any thermal injury. If at any point a bulky tumor impedes visualization of the posterior plane, use of a 30° upward-facing lens may be warranted, which may improve visualization of the underside of the bladder.

Fig. 16.3

(a) Distal right prostatic pedicle seen during a RARC where the application of a laparoscopic stapler would be potentially hazardous due to the proximity of the rectum. (b) Application of Hem-o-lok clip allowing precise division of pedicle anterior to rectum (R = rectum, P = pedicle, SV = seminal vesicle, EF = endopelvic fascia)

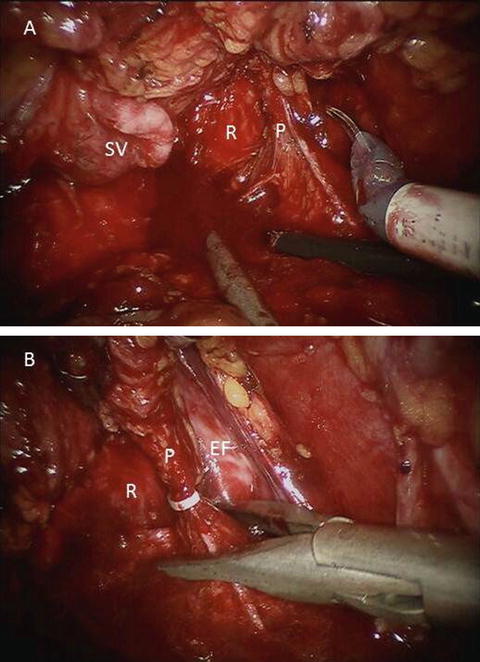

Although the extirpative portion of RARC is undeniably the focus of the procedure, the prognostic and therapeutic benefits of an extended pelvic lymphadenectomy (PLND) at the time of radical cystectomy are also important and have been well established [20]. The ability to perform an adequate pelvic lymph node dissection during RARC has been a popular target for opponents of the robotic approach. However, this has been refuted by several authors [10, 21, 22], and we uphold that a meticulous dissection of any template can be performed robotically if the surgeon is committed to this goal. One of the most challenging aspects of the PLND is performing an adequate and safe dissection of the lymphatic tissue in the bifurcation of the common iliac vessels. The difficulty of dissection can be decreased by medial mobilization of the external iliac vessels and all associated lymphatic tissue. This will expose the medial aspect of the psoas muscle and the most proximal aspect of the obturator nerve while releasing all lateral attachments of this nodal packet as shown in (Fig. 16.4a). It will further allow the surgeon to return to the medial side of the vessels and easily withdraw the entire lymph node packet from the bifurcation of the vessels (Fig. 16.4b). Overall, this will not only help decrease the risk of a vascular injury to the hypogastric vessels and alleviate the anxiety associated with dissection in this challenging area but also allow excellent access for the hypogastric vein dissection (Fig. 16.4c).

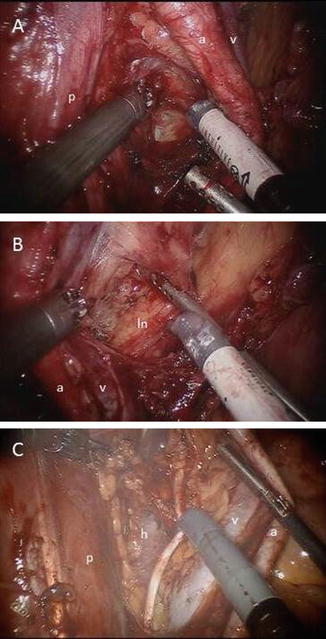

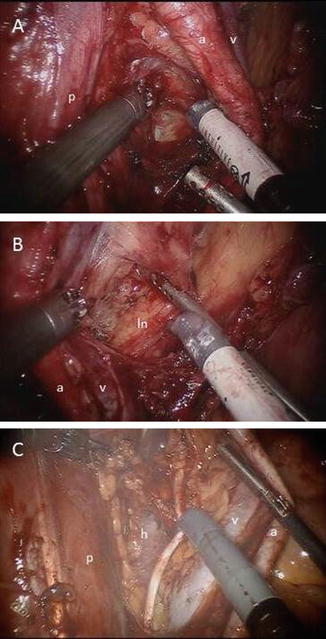

Fig. 16.4

(a) Medial mobilization of left external iliac vessels with the obturator/hypogastric lymph node packet. (b) Separation of lymph node packet from external iliac vessels. (c) Exposure of left hypogastric vein and obturator nerve (a = external iliac artery, v = external iliac vein, p = psoas muscle, ln = left hypogastric/obturator lymph node packet, h = hypogastric vein)

With the use of the above-mentioned advice for patient and instrument selection, perioperative care pathways, and intraoperative technique, we believe that many complications can be avoided.

Management of Operative Complications

As described in the subsection above, avoidance of complications may be equally important to the ability of managing these same complications, most of which can be controlled robotically. Perhaps one of the most common intraoperative issues involves shortened ureteral length. Whether one has decreased length due to patient habitus or the necessity of decreasing length to attain negative margins, this can create difficulty in ureteroileal anastomoses. Furthermore, one can find additional length through elongation of the created ileal conduit (or neobladder limb). To enable adequate visualization of the anastomosis, one may need to lengthen the incision used for extracorporeal diversion, and the surgeon should not hesitate to do so, since this may decrease the possibility of ureteral tension and improve the quality of the anastomosis, reducing the chance of postoperative stricture.

While ureteral length may be a common intraoperative issue, a less common but more dangerous complication is intraoperative vascular injury, often experienced during lymph node dissection. Should this occur, vascular injuries can often be managed robotically. Additionally, a suture should be ready at all times to enable quick ligation of a bleeding vessel. In the setting of a venous injury the pneumoperitoneum should be increased to 20 mmHg to help tamponade the bleeding. In the case of a small to medium vessel with a visible stump or partial division, a clip may be employed. However, if a large en-face injury occurs (for example, in the external iliac vein), it may be necessary to grasp the opening (or apply pressure) with the left hand instrument (Fenestrated Bipolar) while placing a figure-of-eight suture around the defect with the contralateral hand. In this situation, the scissors in the right hand will need to be exchanged to a needle driver while the left hand maintains hemostasis. A shorter suture (≤6 in.) will suffice and ensure ease of tying. In the event of a larger injury, proximal and distal control of the vessel may be required to adequately visualize and repair the defect. To accomplish this maneuver, the bedside assistant will likely be required to hold pressure on the injury while the console surgeon gains vascular control. Once the dissection is complete, either a tourniquet or laparoscopic bulldog clamps may be used. While controlling bleeding vessels, it is imperative to be cognizant of adjacent structures, particularly the obturator nerve, which can inadvertently be injured if one is not careful.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree