Chapter 7 Surgical Anatomy of the Abdomen and Pelvis

ANTERIOR ABDOMINAL WALL

The abdominal wall is made up of four structural layers beneath the skin: (1) subcutaneous tissue and superficial fascial layers, (2) muscles and transversalis fascia, (3) deep fascia of the rectus sheath and the extraperitoneal fascia, and (4) parietal peritoneum (Fig. 7-1). Interspersed among these layers are several important nerves and blood vessels.

Deep Fascia of the Rectus Sheath and Extraperitoneal Fascia

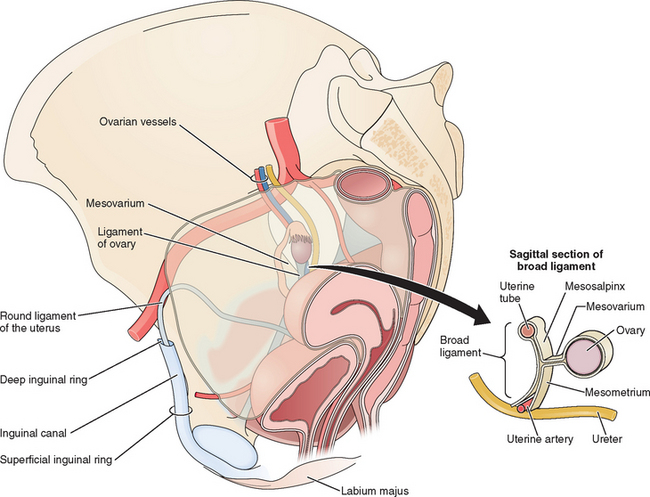

The inguinal canal is about 4 cm long and runs parallel to the inguinal ligament. The inguinal canal has an anterior wall formed by the aponeurosis of the external oblique, an inferior wall formed by the inguinal ligament, a superior wall formed by arching fibers of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles, and a posterior wall formed by the transversalis fascia. A defect, or more precisely a tubular evagination, of the transversalis fascia forms the deep inguinal ring, through which the round ligament enters the inguinal canal. This ring lies midway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic symphysis. Medial to the deep inguinal ring are the inferior epigastric vessels. The opening of the aponeurosis of the external oblique superior to the pubic tubercle is the superficial inguinal ring. Through it the round ligament, the terminal part of the ilioinguinal nerve, and the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve exit the inguinal canal (see Fig. 7-1).

Nerves

These nerves are particularly at risk in lower abdominal incisions, which are the most common causes of abdominal wall pain as a result of nerve entrapment by suture or scar tissue.1 For this reason, knowledge of the course of the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves in the anterior abdominal wall can help avoid injury during laparotomy and laparoscopic surgery. Data from cadaveric studies suggest that injury to these nerves can be minimized during laparoscopy by making transverse skin incisions and placing laparoscopic trocars at or above the level of the anterior superior iliac spine.2 In cases of chronic abdominal pain caused by these nerves, an injection of local anesthetic at a site approximately 3 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine will often provide relief.

Blood Vessels

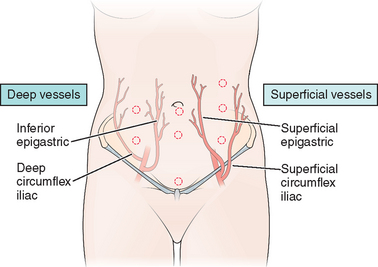

The major vessels in the anterior abdominal wall can be divided into deep and superficial vessels (Fig. 7-2).3 The superficial vessels include the superficial epigastric and the superficial circumflex iliac vessels. These vessels are branches of the femoral artery and vein. They course bilaterally through the subcutaneous tissue of the abdominal wall, branching as they proceed toward the head of the patient.

Figure 7-2 Anterior abdominal wall blood vessels.

(Modified from Hurd WW, Bude RO, DeLancey JOL, Newman JS: The location of abdominal wall blood vessels in relationship to abdominal landmarks apparent at laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 171:642–646, 1994.)

To avoid vessel injuries, these superficial vessels can often be seen before secondary laparscopic port placement by transillumination of the abdominal wall using the intra-abdominal laparoscopic light source.3 Injury to these vessels during trocar placement can result in a palpable hematoma that will be found to be located anterior to the fascia on computed tomography (CT) scan.4 In unusual cases, the hematoma can dissect down into the labia majora.

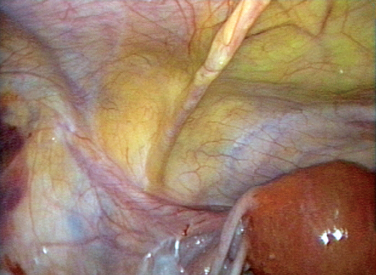

The course of the inferior epigastric vessels can often be visualized at laparoscopy as the lateral umbilical fold because of the absence of the posterior rectus sheath below the arcuate line (Fig. 7-3).5 Injury to these vessels can result in life-threatening hemorrhage that must be quickly controlled by occluding the lacerated vessels with electrosurgery or precisely placed sutures.

If these vessels cannot be visualized (usually because of excess tissue), trocars should be place approximately 8 cm lateral to the midline and 8 cm above the pubic symphysis.3 On the right side of the abdomen, this point approximates McBurney’s point, located one-third the distance from the anterior superior iliac spine to the umbilicus. The corresponding point on left is sometimes referred to as Hurd’s point.

Peritoneal Landmarks

Peritoneal Folds

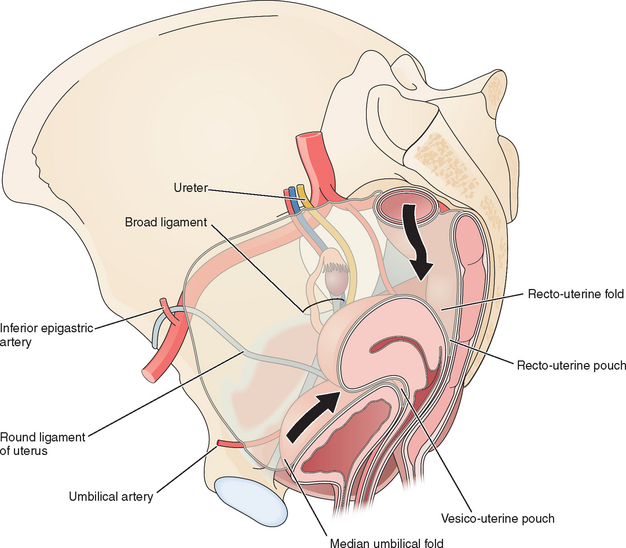

Several useful landmarks can be used to guide the laparoscopic surgeon to avoid injury to important retroperitoneal structures. Two midline and two bilateral pairs of peritoneal folds can usually be seen on the anterior abdominal wall at laparoscopy (Fig. 7-4). The falciform ligament, which is the remnant of the ventral mesentery and contains the obliterated umbilical vein in its free edge, can be seen in the midline above the umbilicus extending to the liver. The median umbilical fold, which contains the urachus, can usually be seen in the midline below the umbilicus extending to the bladder. Although the urachus normally closes before birth, it should be avoided during secondary trocar placement, both because it can be difficult to penetrate and in rare cases can remain patent to the bladder.

On each side of the urachus lie the medial umbilical folds. These landmarks contain the obliterated umbilical arteries and extend from the umbilicus to the anterior division of the internal iliac artery. Lateral to these, the lateral umbilical folds can be seen in 82% of patients.5 These are the most important structures to the laparoscopist, because they contain the inferior epigastric vessels and knowing their location can help the laparoscopist avoid injury to these large vessels during placement of secondary laparoscopic ports.

Peritoneal pouches normally exist between the pelvic organs (see Fig. 7-4). The vesico-uterine pouch is located anteriorly between the uterus and bladder. The ventral margin of the bladder can be visualized in approximately half of patients behind the anterior abdominal wall peritoneum and is important for secondary trocar placement, especially after previous abdominal surgery.5 The dorsal bladder margin can often be visualized on the anterior uterus and is used as a landmark during dissections during hysterectomy.

UPPER ABDOMEN

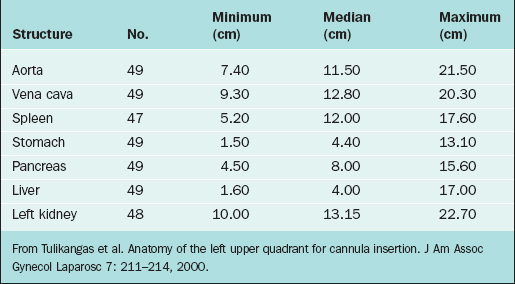

For the left upper quadrant technique, the Verres needle and primary trocar are placed into the abdomen 2 cm below the subcostal arch at the midclavicular line. It is important to know what anatomic structures lie close to this area to avoid injury during insertion of the primary cannula. The anatomic structures at risk of injury in this area include (from posterior to anterior) the spleen, splenic flexure of the colon, stomach, and left lobe of the liver. Although relatively few series using the left upper quadrant approach have been reported, it appears that the colon might be the organ at greatest risk of injury using this technique.6 Table 7-1 lists the common body structures and distances from the left upper quadrant point from CT scan data.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree