Stomach

2.1 Crush artifact vs. Signet-ring cell carcinoma

2.2 Signet-ring cell change vs. Signet-ring cell carcinoma

2.3 Xanthoma vs. Signet-ring cell carcinoma

2.4 Iron pill gastritis vs. Dysplasia

2.6 Russell body gastritis vs. Signet-ring cell carcinoma

2.9 Watermelon stomach (gastric antral vascular ectasia) vs. Chemical gastropathy

2.10 Mucosal calcinosis vs. Parasitic gastritis

2.11 Proton pump inhibitor effect vs. Fundic gland polyp and oxyntic gland polyp

2.12 Iron pill gastritis vs. Gastric siderosis

2.13 Colchicine and taxol–associated gastropathy vs. Dysplasia

2.14 Autoimmune gastritis vs. Environmental gastritis

2.15 Sarcina gastropathy vs. Micrococcus

2.16 Ménétrier disease vs. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome

2.17 Ménétrier disease vs. Hyperplastic polyp

2.18 Hyperplastic polyp vs. Syndromic polyps (Juvenile polyposis and Peutz-Jeghers polyposis)

2.19 Pyloric gland adenoma vs. Intestinal-type adenoma

2.20 Pyloric gland adenoma vs. Gastric foveolar-type gastric adenoma

2.21 Oxyntic gland polyp/adenoma vs. Fundic gland polyp

2.22 Lymphoepithelial-like carcinoma vs. Lymphoma

2.23 Metastatic lobular breast carcinoma vs. Signet-ring cell gastric carcinoma

2.24 Well-differentiated neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumor vs. Adenocarcinoma

2.25 Type 1 endocrine tumor vs. Type 2 endocrine tumor

2.26 Type 1 endocrine tumor vs. Type 3 endocrine tumor

2.27 Mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma vs. Chronic gastritis

2.28 Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma vs. Carcinoma

2.29 Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) vs. Inflammatory fibroid polyp

2.30 Epithelioid gastrointestinal tumor vs. Carcinoma

2.31 Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) vs. Schwannoma

2.32 Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) vs. Glomus tumor

2.33 Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), pediatric type vs. Plexiform fibromyxoma

2.1 Crush artifact vs. Signet-ring cell carcinoma

| Crush Artifact | Signet-Ring Cell Carcinoma | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Any age; male = female | Mean age mid-50; males > females |

| Location | Usually at the edges of the specimen | Predominantly antrum (60%); less commonly body (20%), cardia/fundus (10%), diffuse/entire stomach (1%) |

| Symptoms | None | Related to extent of tumor growth; most commonly present with early-onset satiety, decreased appetite, reflux |

| Signs | None | Palpable stomach with occasional succussion splash, enlarged supraclavicular and/or axillary lymph nodes, anemia, obstruction |

| Etiology | Related to the biopsy procedure and specimen processing | Environmental risk factors include dietary factors (e.g., nitrites) and smoking. Increased risk in association with autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis. A subset of cases are familial and show inactivating germline mutations of the CDH1 gene |

| Histology | ||

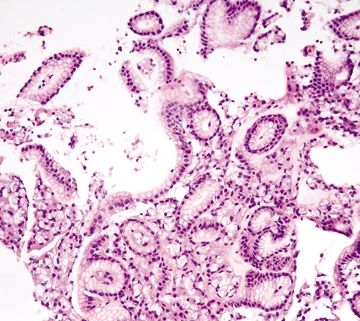

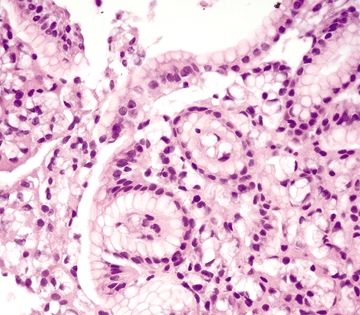

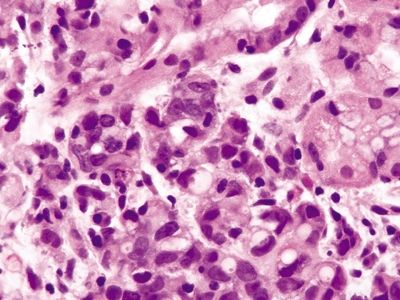

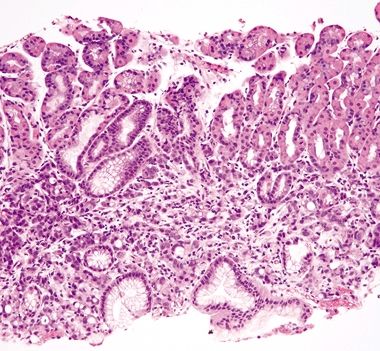

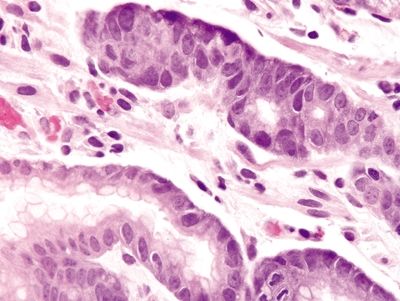

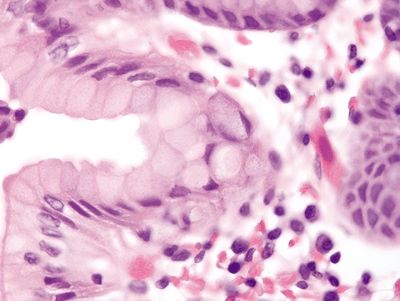

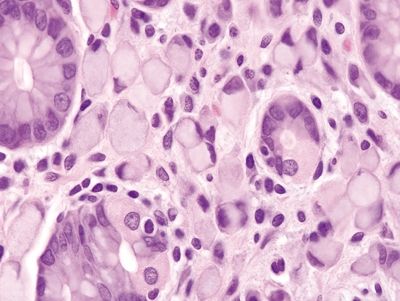

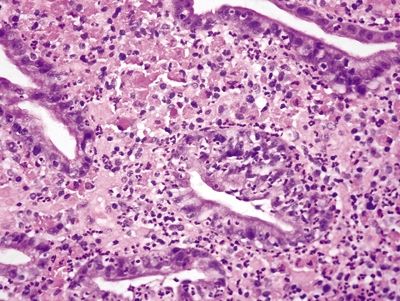

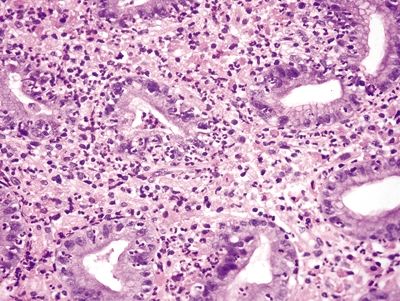

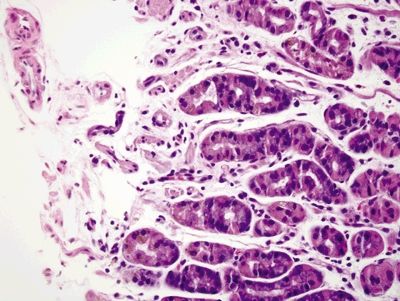

| 1. Crushed oxyntic glands with predominance of mucous neck cells (Fig. 2.1.1) 2. Mucous cells located within the lumina of the glands (Fig. 2.1.2) 3. Focal mucosal hemorrhage 4. No background dysplasia | 1. Cells with large, atypical, hyperchromatic, and eccentrically placed nuclei and intracytoplasmic mucin vacuoles that displace the nucleus (Fig. 2.1.3) 2. Individual or poorly formed groups of cells 3. Mucous cells generally located outside the lumina of the glands, within the lamina propria; however, in familial forms can be located within the glands, underneath the foveolar cells, and within the basement membrane (Fig. 2.1.4) 4. Increased mitotic rate (Fig. 2.1.5) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | None | Surgical resection for early-stage disease; adjuvant chemoradiation for late-stage disease |

| Prognosis | Related to any other pathology present in the specimen | Related to stage and location of disease, but overall poor prognosis; worst prognosis for proximal late-stage disease |

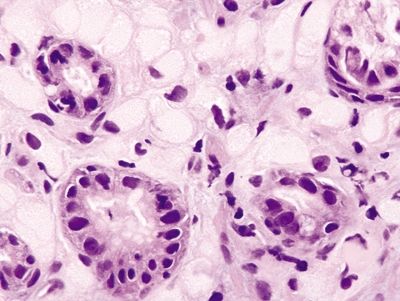

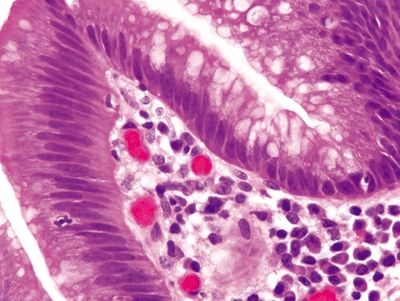

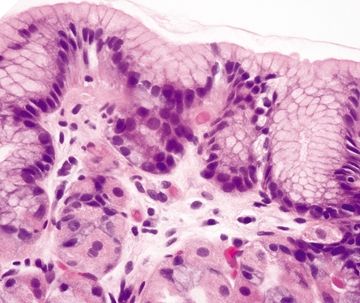

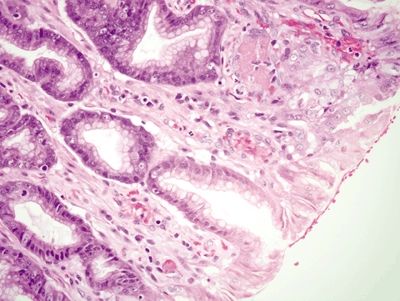

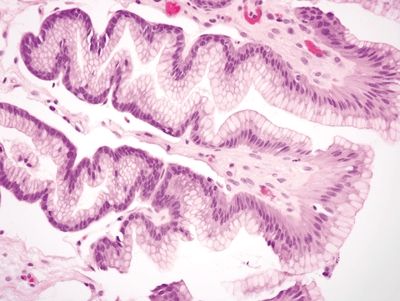

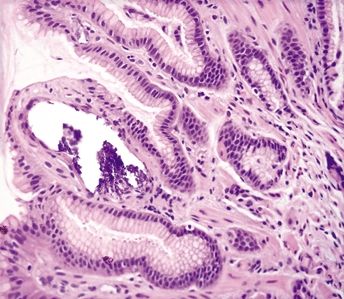

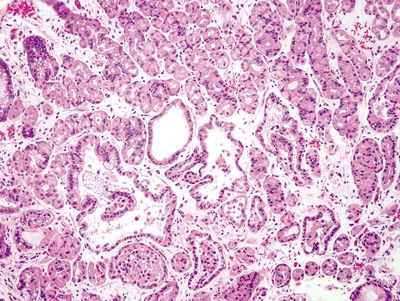

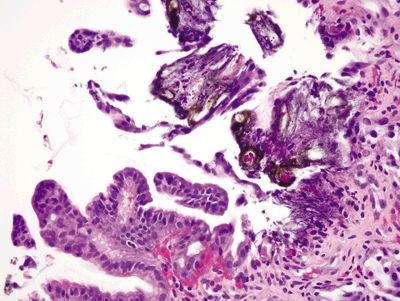

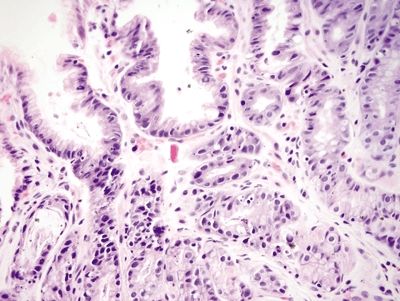

Figure 2.1.1 Crushed oxyntic glands. Distorted and crushed glands.

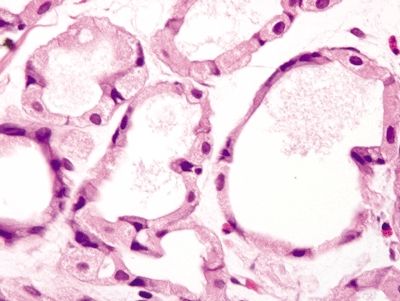

Figure 2.1.2 Crushed oxyntic glands. Distorted glands with displaced mucous cells located within the gland lumen.

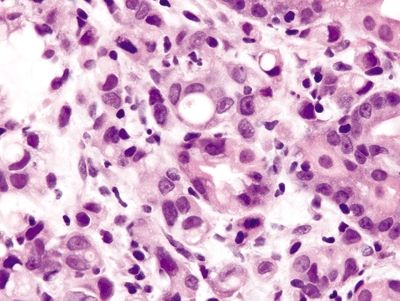

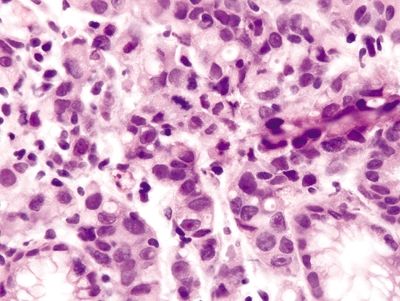

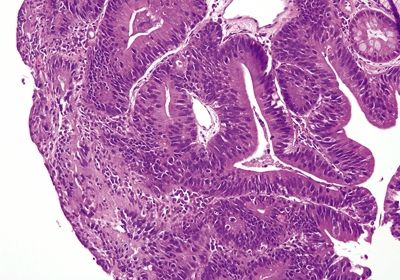

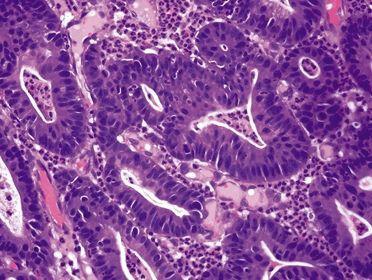

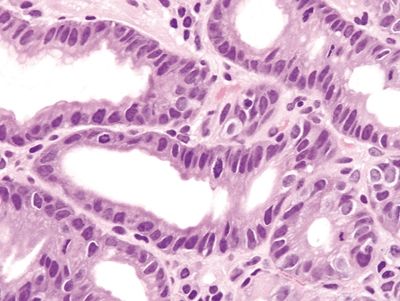

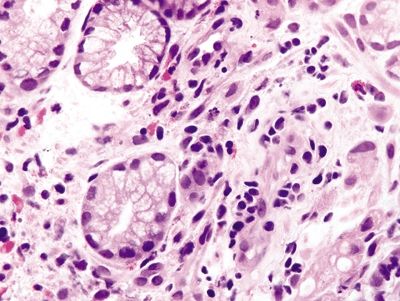

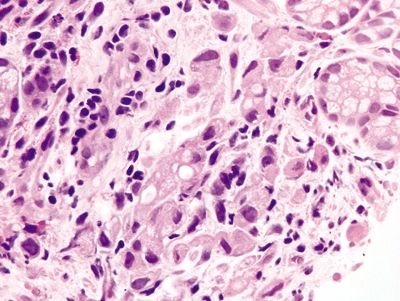

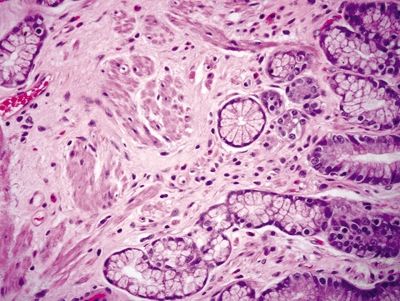

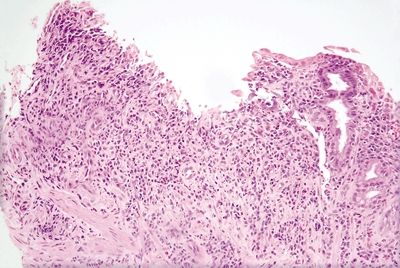

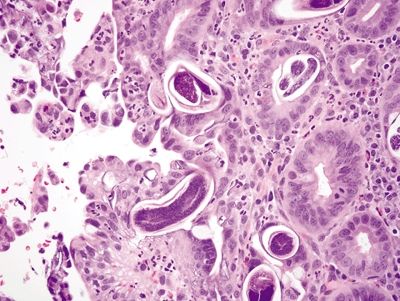

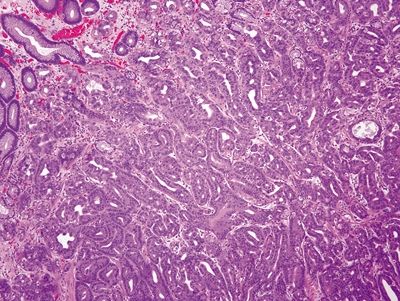

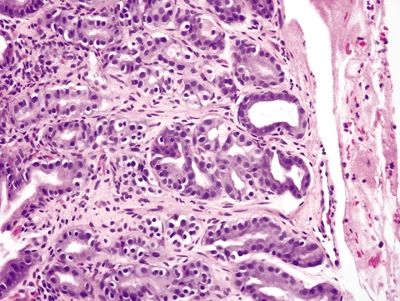

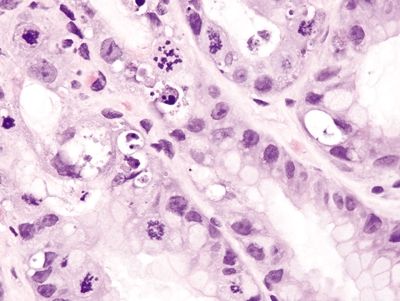

Figure 2.1.3 Signet-ring cell carcinoma. Signet ring cells with prominent intracytoplasmic mucin vacuoles infiltrating as clusters of cells in the lamina propria.

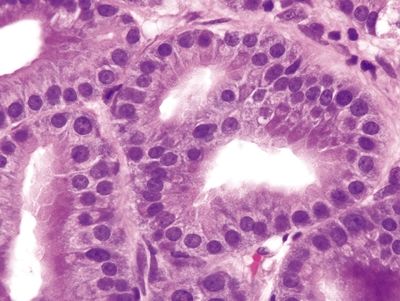

Figure 2.1.4 Signet-ring cell carcinoma. Signet-ring cell carcinoma infiltrating through the lamina propria.

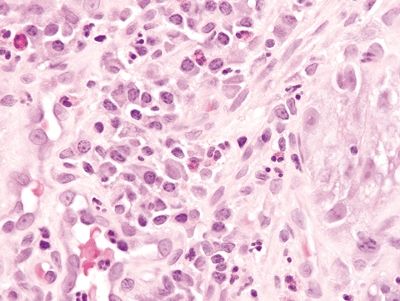

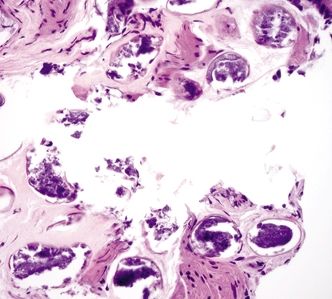

Figure 2.1.5 Signet-ring cell carcinoma. Signet ring cells with hyperchromatic, pleomorphic nuclei and prominent mitoses.

2.2 Signet-ring cell change vs. Signet-ring cell carcinoma

| Signet-Ring Cell Change | Signet-Ring Cell Carcinoma | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Any age; males = females | Mean age mid-50; males > females |

| Location | Any location | Predominantly antrum (60%); less commonly body (20%), cardia/fundus (10%), diffuse/entire stomach (1%) |

| Symptoms | Related to any underlying condition; can present with diarrhea and abdominal pain | Related to extent of tumor growth; patients commonly present with early satiety, decreased appetite, reflux |

| Signs | Related to any underlying condition; can present with abdominal tenderness or fever | Palpable stomach with occasional succession splash, enlarged supraclavicular and/or axillary lymph nodes, anemia, obstruction |

| Etiology | Displacement and distortion of cells secondary to sloughing in the setting of mucosal damage often seen in association with pseudomembranous colitis or gastric ulcers | Environmental risk factors include dietary factors (e.g., nitrites) and smoking. Increased risk in association with autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis. Inherited—48% with inactivating germline mutations of the CDH1 gene |

| Histology | ||

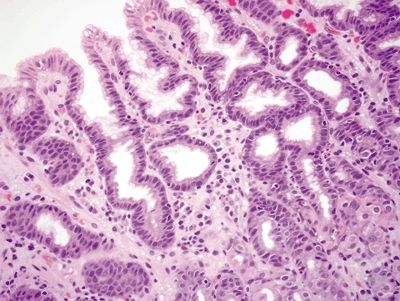

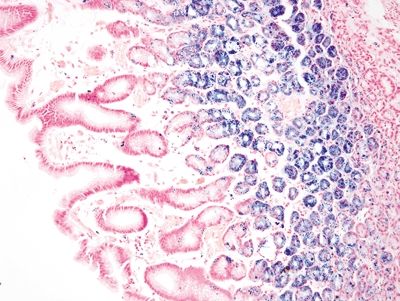

| 1. Background often shows a fibroinflammatory infiltrate composed of neutrophils, mucus, and fibrin extending upwards from the surface epithelium and focal epithelial necrosis 2. Sloughed epithelial cells congregate in the lumen and become distorted such that the intracytoplasmic mucin vacuole displaces the nucleus imparting a signet-ring cell appearance (Fig. 2.2.1) 3. Signet ring cells contained within the basement membrane of the glands; no extension into the lamina propria (Fig. 2.2.2) 4. Minimal nuclear atypia 4. Prominent nuclear atypia (Fig. 2.2.8) 5. Few to no mitoses or apoptotic bodies | 1. Cells with large, atypical, hyperchromatic, and eccentrically placed nuclei and intracytoplasmic mucin vacuoles that displace the nucleus (Figs. 2.2.4 and 2.2.5) 2. Individual or poorly formed groups of cells (Fig. 2.2.6) 3. Malignant cells infiltrate through the basement membrane into the lamina propria and often into the submucosa and deeper tissue; in familial forms can be located within the glands, underneath the foveolar cells, and within the basement membrane (Fig. 2.2.7) 5. Frequent mitoses (Figs. 2.2.5 and 2.2.8) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Specific to any underlying etiology | Surgical resection for early-stage disease; adjuvant chemoradiation for late-stage disease |

| Prognosis | Varies; related to any underlying etiology. | Related to stage and location of disease, but overall poor prognosis; worst prognosis for proximal late-stage disease |

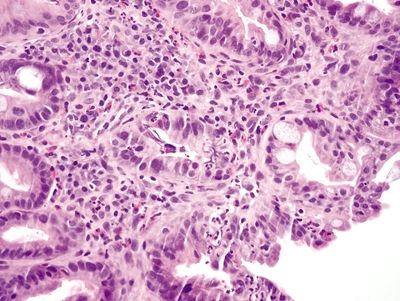

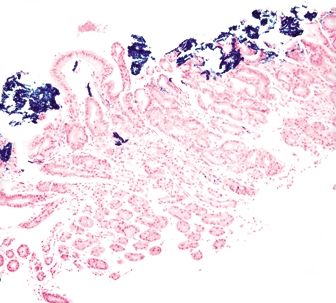

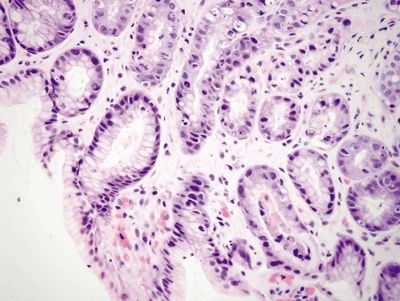

Figure 2.2.1 Signet-ring cell change. Focal ulceration and acute inflammation associated with signet-ring cell change.

Figure 2.2.2 Signet-ring cell change. Signet ring cells within the lumen of glands confined within the basement membrane.

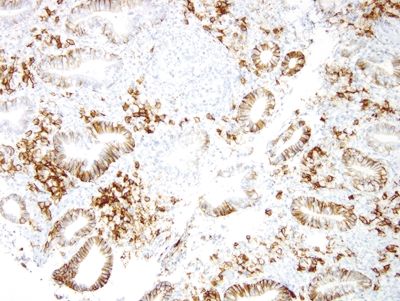

Figure 2.2.3 Signet-ring cell change. Signet-ring cell change showing positive immunolabeling for E-cadherin.

Figure 2.2.4 Signet-ring cell carcinoma. Markedly atypical signet ring cells.

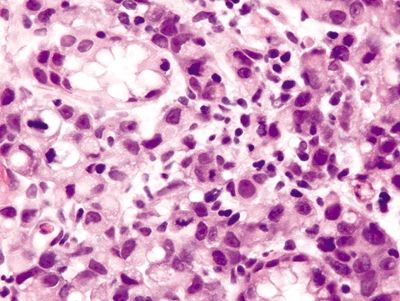

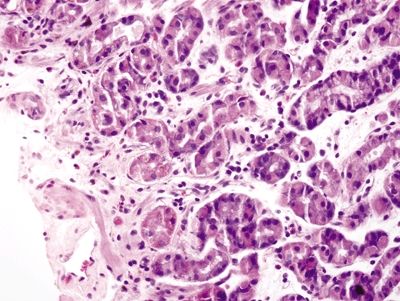

Figure 2.2.5 Signet-ring cell carcinoma. Infiltrating signet ring cells with prominent mitoses.

Figure 2.2.6 Signet-ring cell carcinoma. Infiltrating signet ring cells located outside of the basement membrane.

Figure 2.2.7 Signet-ring cell carcinoma. Signet ring cells infiltrating within the lamina propria.

Figure 2.2.8 Signet-ring cell carcinoma. Signet-ring cell carcinoma with marked nuclear atypia and mitotic figures.

2.3 Xanthoma vs. Signet-ring cell carcinoma

| Xanthoma | Signet-Ring Cell Carcinoma | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Typically adults (mean age 60 years old); male predominance | Mean age mid-50; males > females |

| Location | Lesser curvature; pylorus | Predominantly antrum (60%); less commonly body (20%), cardia/fundus (10%), diffuse/entire stomach (1%) |

| Symptoms | Incidental lesions; nonspecific symptoms include dyspepsia, abdominal pain, and vomiting related to association with other gastric conditions including ulcers, bile reflux, and chronic gastritis | Related to extent of tumor growth; most commonly present with early satiety, decreased appetite, reflux |

| Signs | None; incidental lesion | Palpable stomach with occasional succession splash, enlarged supraclavicular and/or axillary lymph nodes, anemia, obstruction |

| Etiology | Presumably due to prior or current gastric irritation; not associated with hyperlipidemia or skin xanthomas | Environmental risk factors include dietary factors (e.g., nitrites) and smoking Increased risk in association with autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis Inherited—48% with inactivating germline mutations of the CDH1 gene |

| Histology | ||

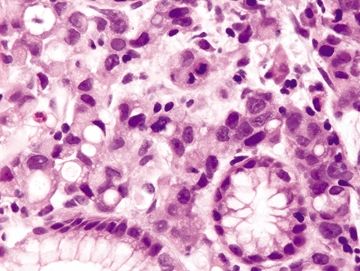

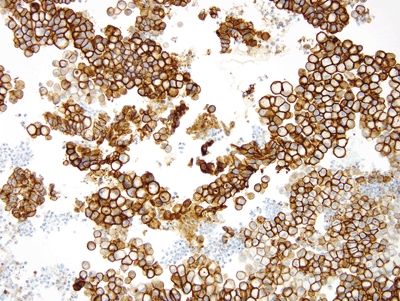

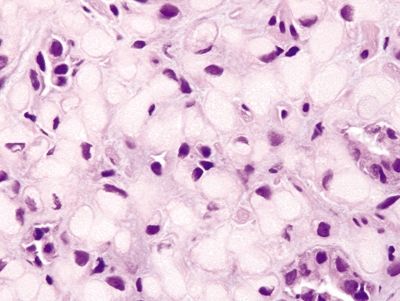

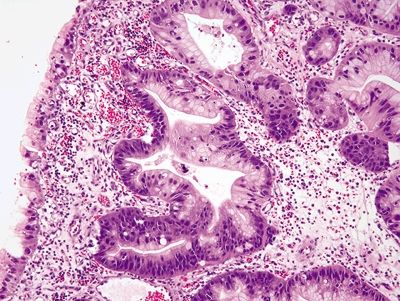

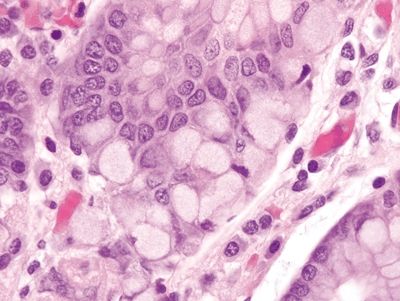

| 1. Lipid-laden macrophages in the lamina propria, with bland centrally placed nuclei (Figs. 2.3.1 and 2.3.2) 2. Lesions usually less than 3 mm 3. No increase in mitoses (Fig. 2.3.2) | 1. Cells with large, atypical, hyperchromatic, and eccentrically placed nuclei and intracytoplasmic mucin vacuoles that displace the nucleus (Fig. 2.3.3) 2. Diffuse infiltration by individual or poorly formed groups of cells, often with dense desmoplastic stroma (Figs. 2.3.4 and 2.3.5) 3. Increased mitotic rate | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| ||

| Treatment | None; specific treatment for any associated underlying conditions | Surgical resection for early-stage disease; adjuvant chemoradiation for late-stage disease |

| Prognosis | Benign; of little significance; reported association with Helicobacter gastritis | Related to stage and location of disease, but overall poor prognosis; worst prognosis for proximal late-stage disease |

Figure 2.3.1 Xanthoma. Lipid-laden macrophages diffusely infiltrating the lamina propria.

Figure 2.3.2 Xanthoma. Lipid-laden macrophages with foamy cytoplasm and minimal atypia.

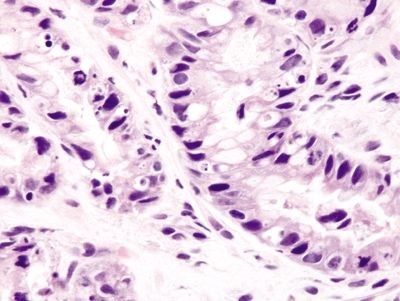

Figure 2.3.3 Signet-ring cell carcinoma. Signet ring cells with large, atypical nuclei and prominent intractyoplasmic mucin vacuoles.

Figure 2.3.4 Signet-ring cell carcinoma. Diffuse infiltration of the mucosa extending into the submucosa.

Figure 2.3.5 Signet-ring cell carcinoma. Signet ring cells with prominent mitoses.

2.4 Iron pill gastritis vs. Dysplasia

| Iron Pill Gastritis | Dysplasia | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Any age; predominantly female | Typically adults; predominantly males 50s–70s |

| Location | Any part of the stomach | Predominantly in the antrum |

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, vomiting, and some present with GI bleeding | No specific symptoms, unless associated with invasive disease (abdominal pain, early satiety, gastric reflux) |

| Signs | None; patient may have a history of iron deficiency anemia | No specific signs |

| Etiology | Unknown, likely related to concentration-dependent chemical toxicity of iron and its metabolites; up to 50% of patients have comorbid conditions that predispose them to gastric injury | Precancerous lesion associated with history of chronic Helicobacter infection and autoimmune atrophic gastritis and familial adenomatous polyposis. |

| Histology | ||

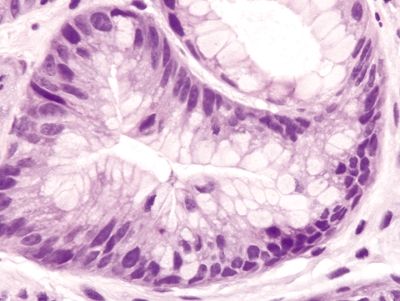

| 1. Mucosal erosion with associated acute and chronic inflammation, granulation tissue and/or necrosis (Fig. 2.4.1) 2. Reactive epithelial changes consisting of enlarged nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Fig. 2.4.2) 3. Retained architectural structure 4. Yellow-brown-gray discoloration of the epithelium (H&E) due to iron deposition (Fig. 2.4.2) 5. Mitoses limited to the base of crypts | 1. Low-grade dysplasia characterized by hyperchromatic, elongated, and pseudostratified cells (Figs. 2.4.4 and 2.4.5) 2. Not associated with erosion or ulceration 3. High-grade dysplasia shows architectural distortion including glandular crowding and nuclear pseudostratification (Fig. 2.4.6) 4. Most lesions associated with background intestinal metaplasia (Fig. 2.4.5) 5. Not pigmented 6. Mitoses present at both the base and tips of crypts (Fig. 2.4.6) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Symptomatic treatment; supplement with liquid iron | If polypoid, removal of polyp; for polypoid adenomatous and flat dysplasia, repeat biopsy with representative sampling of the entire stomach to evaluate for invasive disease |

| Prognosis | Good; symptoms usually resolve quickly | Variable; low-grade dysplasia sometimes regresses spontaneously, while high-grade dysplasia usually persists and can progress to invasive carcinoma |

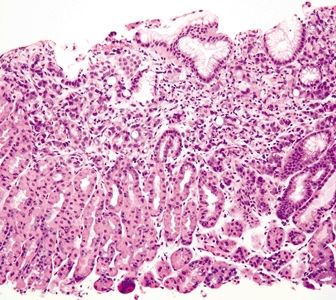

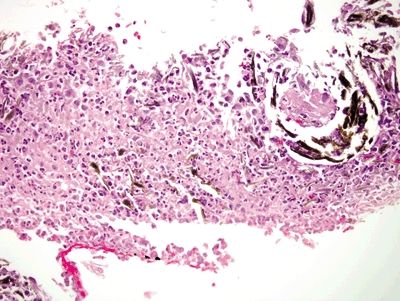

Figure 2.4.1 Iron pill gastritis. Mucosal ulceration with mixed acute and chronic inflammation, necrosis, and iron deposition.

Figure 2.4.2 Iron pill gastritis. Reactive changes in iron pill gastritis.

Figure 2.4.3 Iron pill gastritis. Iron stain in iron pill gastritis.

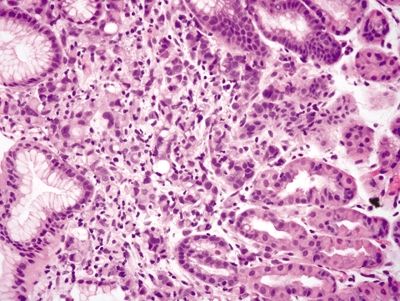

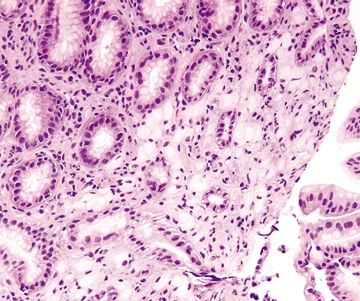

Figure 2.4.4 Dysplasia. Low-grade dysplasia showing nuclear crowding, elongation, and pseudostratification.

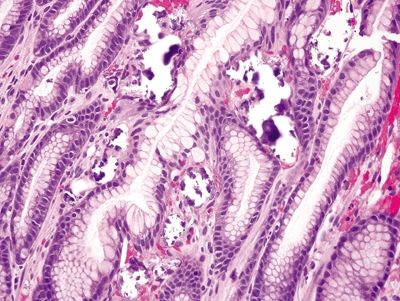

Figure 2.4.5 Dysplasia. Low-grade dysplasia and intestinal metaplasia.

Figure 2.4.6 Dysplasia. High-grade dysplasia showing pleomorphism, mucin loss, and loss of nuclear polarity.

2.5 Reactive changes of stress gastritis vs. In situ signet-ring cell carcinoma in patients with CDH1 germline mutations

| Reactive Changes of Stress Gastritis | In Situ Signet-Ring Cell Carcinoma in Patients with CDH1 Germline Mutations | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Typically older adults though can occur at any age; no gender predominance | Typically middle-aged adults (mean age 38); no gender predominance |

| Location | Any location | Often in the proximal third of the stomach |

| Symptoms | Abrupt abdominal pain, vomiting, and bleeding | Few, if any due to increased surveillance and prophylactic surgery. Advanced lesions present with abdominal pain, early satiety, vomiting, and weight loss |

| Signs | Depends on the extent of GI bleeding; in mild cases patients present with light-headedness, dizziness, and fatigue; in more severe cases patients present with unstable vital signs. Endoscopy shows shallow erosions and edematous mucosa with petechial hemorrhages | Nonspecific. Surveillance endoscopy occasionally detects early lesions |

| Etiology | Acute stress injury due to various etiologies, most commonly alcohol, NSAIDs, and ischemia | The CDH1 gene encodes for E-cadherin, an intercellular adhesion molecule Inactivating mutations are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern with 70% penetrance. The average lifetime risk of gastric cancer by age 80 is 67% for men and 83% for women. Women are also at an increased risk of lobular breast carcinoma |

| Histology | ||

| 1. Dark, hyperchromatic, enlarged, often pleomorphic, nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Figs. 2.5.1 and 2.5.2) 2. Changes generally limited to the deep mucosa with normal surface maturation (Fig. 2.5.3) 3. Background usually shows erosion or ulceration and acute and or chronic inflammation (Fig. 2.5.4) | 1. Early lesions are essentially in situ signet-ring cell carcinoma characterized by signet ring cells scattered within glands, beneath foveolar cell nuclei, and within the basement membrane (Figs. 2.5.5 and 2.5.6) 2. Late lesions histologically similar to sporadic diffuse gastric carcinoma a. Cells with large, atypical, hyperchromatic, and eccentrically placed nuclei; inconspicuous nucleoli; and intracytoplasmic mucin vacuoles that displace the nucleus (Fig. 2.5.7) b. Individual or poorly formed groups of cells (Fig. 2.5.7) c. Increased mitotic rate d. Desmoplastic response | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Mainstay of therapy is supportive care including intravenous fluids and blood transfusion as well as pharmaceutical therapy with PPIs and H2 blockers and discontinuation of any inciting drugs | Identified carriers are often treated with prophylactic gastrectomy. In advanced disease, resection with or without neoadjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiation is the primary treatment. Genetic screening is important to identify at-risk families followed by routine surveillance for carriers |

| Prognosis | Very good; most patients recover within a few days to weeks | Variable; prognosis is generally very good for early detected lesions, but advanced disease portends a very poor prognosis |

Figure 2.5.1 Reactive epithelial changes with enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei and conspicuous mitoses.

Figure 2.5.2 Reactive epithelial changes with enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei with prominent nucleoli.

Figure 2.5.3 Reactive changes predominant in the crypts with normal surface maturation.

Figure 2.5.4 Reactive changes in association with granulation tissue.

Figure 2.5.5 In situ signet-ring cell carcinoma.

Figure 2.5.6 In situ signet-ring cell carcinoma with pagetoid spread.

Figure 2.5.7 Infiltration of the lamina propria by malignant signet ring cells.

2.6 Russell body gastritis vs. Signet-ring cell carcinoma

| Russell Body Gastritis | Signet-Ring Cell Carcinoma | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Typically adults; no gender predominance | Mean age mid-50; males > females |

| Location | Lamina propria of the antrum and body | Predominantly antrum (60%); less commonly body (20%), cardia/fundus (10%), diffuse/entire stomach (1%) |

| Symptoms | Nonspecific; usually presents in association with chronic gastritis; patients present with the common symptoms of vague abdominal pain, dyspepsia, nausea | Related to extent of tumor growth; most commonly present with early satiety, decreased appetite, reflux |

| Signs | Few, if any | Palpable stomach with occasional succussion splash, enlarged supraclavicular and/or axillary lymph nodes, anemia, obstruction |

| Etiology | Unknown; some cases are thought to be associated with Helicobacter pylori infection to suggest a causal relationship, but no conclusive evidence exists; other associations include monoclonal gammopathy and EBV-related gastric carcinoma | Environmental risk factors include dietary factors (e.g., nitrites) and smoking. Increased risk in association with autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis. Inherited—48% with inactivating germline mutations of the CDH1 gene |

| Histology | ||

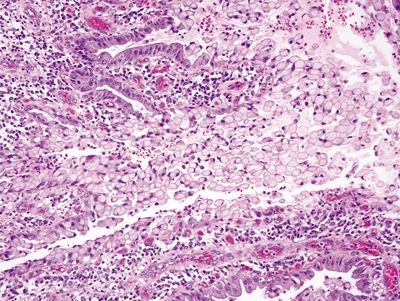

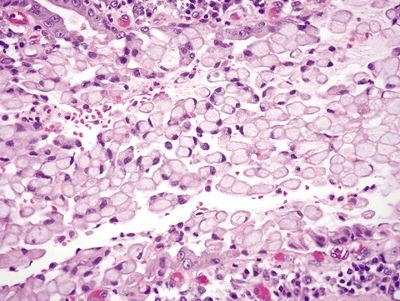

| 1. Focal collections of plasma cells with cytoplasmic eosinophilic globules composed of immunoglobulins (Russell bodies) that displace the nucleus (Fig. 2.6.1) 2. Expansion of the lamina propria with distortion of the adjacent gastric glands (Fig. 2.6.2) 3. Background mucosa with diffuse acute and mononuclear chronic inflammatory infiltrate (Fig. 2.6.2) 4. No nuclear atypia | 1. Cells with large, atypical, hyperchromatic, and eccentrically placed nuclei and intracytoplasmic clear, round mucin vacuoles that displace the nucleus (Fig. 2.6.5) 2. Diffuse infiltration of the submucosa by individual or poorly formed groups of cells, often with dense desmoplastic stroma (Fig. 2.6.6) 3. Nonfocal nuclear atypia (Fig. 2.6.7) 4. High mitotic rate | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Given the association with Helicobacter pylori infection, most patients are treated with standard triple-antibiotic therapy | Surgical resection for early-stage disease; adjuvant chemoradiation for late-stage disease |

| Prognosis | Excellent; benign | Related to stage and location of disease, but overall poor prognosis; worst prognosis for proximal late-stage disease |

Figure 2.6.1 Russell body gastritis. Neutrophilic and plasmacytic infiltrate within the glands and lamina propria.

Figure 2.6.2 Russell body gastritis. Diffuse infiltration of the lamina propria, distortion of glands, and marked acute and chronic inflammation.

Figure 2.6.3 Russell body gastritis. CD138 stain highlighting numerous plasma cells.

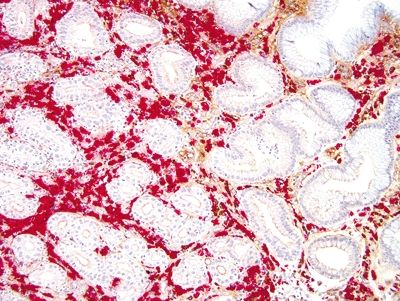

Figure 2.6.4 Russell body gastritis. Kappa- (brown) and lambda-light (red) chain dual stain showing a predominance of lambda-expressing plasma cells.

Figure 2.6.5 Signet-ring cell carcinoma with pleomorphic nuclei infiltrating as single cells.

Figure 2.6.6 Signet-ring cell carcinoma infiltrating the lamina propria.

Figure 2.6.7 Signet-ring cell carcinoma. Markedly atypical signet ring cells.

2.7 Antrum vs. Body

| Antrum | Body | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Any age; male = female | Any age; male = female |

| Location | Distal third of the stomach, extending from the incisura to the pylorus | Center part of Stomach (body and fundus) |

| Symptoms | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Signs | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Etiology | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Histology | ||

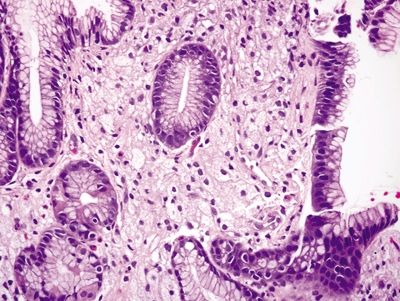

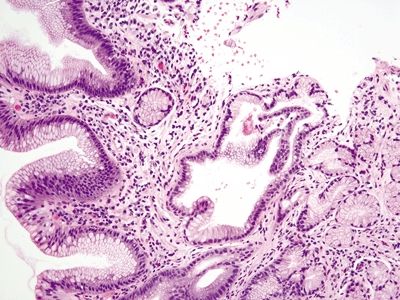

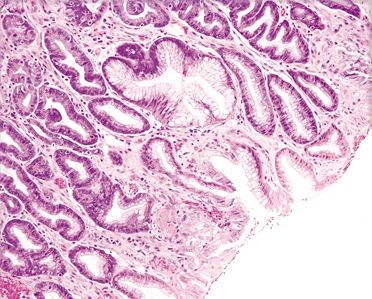

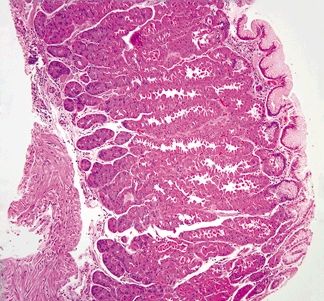

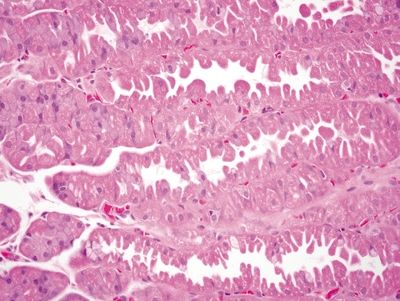

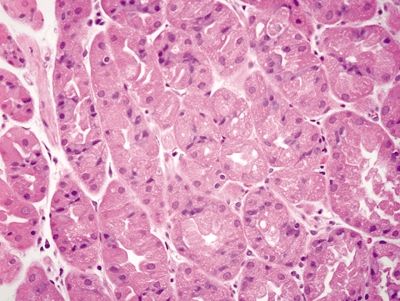

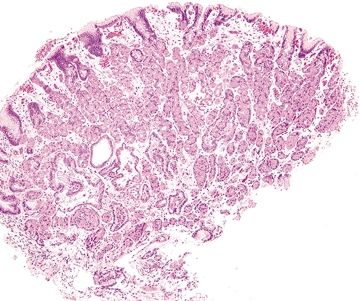

| 1. Loosely packed glands composed of mucinous cells (Figs. 2.7.1 and 2.7.2) 2. Mucinous surface 3. Short pits and branched glands span approximately half of the epithelial thickness; 1:1 ratio of pit:gland (Fig. 2.7.3) | 1. Mucinous surface epithelium with underlying tightly packed glands composed of two cell types—chief cells with basophilic cytoplasm and parietal cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm (Figs. 2.7.4 and 2.7.5) 2. Long pits and tubular glands that span approximately 70% of the epithelial thickness; 1:4 ratio of pit:gland (Fig. 2.7.6) 3. Scattered endocrine cells at the base of crypts that secrete histamine (enterochromaffin-like) 4. Scattered endocrine cells present below the surface epithelium including cells that secrete gastrin, somatostatin, and serotonin (enterochromaffin-like) (Fig. 2.7.2) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Prognosis | Not applicable | Not applicable |

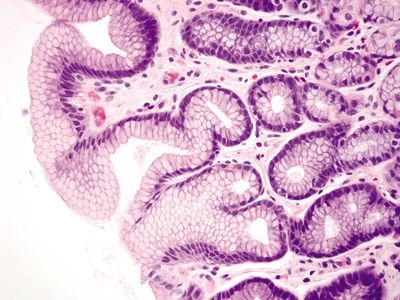

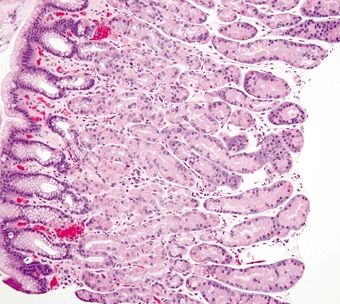

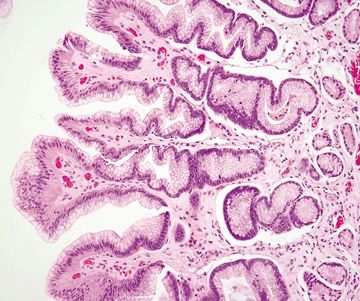

Figure 2.7.1 Antrum. Superficial mucosa of the antrum composed of short mucous pits.

Figure 2.7.2 Antrum. Deep mucosa of the antrum composed of branching mucous glands and scattered endocrine cells.

Figure 2.7.3 Antrum. Antrum architecture composed of short pits and glands in a 1:1 ratio.

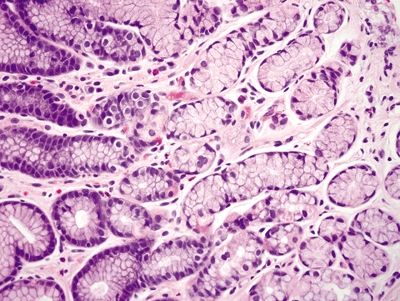

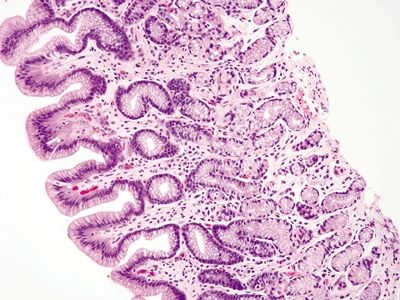

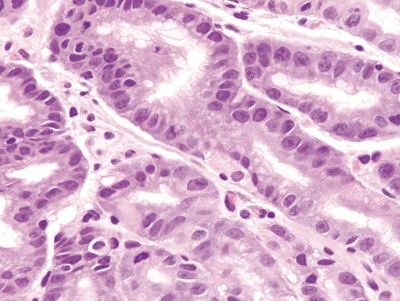

Figure 2.7.4 Body. Superficial mucosa of the body composed of short pits of mucous cells.

Figure 2.7.5 Body. Deep mucosa of the body composed of intermixed parietal and chief cells.

Figure 2.7.6 Body architecture composed of short pits and long glands in a 1:4 ratio.

2.8 Antrum vs. Cardia

| Antrum | Cardia | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Any age; male = female | Any age; male = female |

| Location | Distal third of the stomach, extending from the incisura to the pylorus | Extends from the lower esophageal sphincter to the fundus |

| Symptoms | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Signs | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Etiology | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Histology | ||

| 1. Loosely packed glands composed of mucinous cells (Fig. 2.8.1) 2. Short pits and branched glands that span approximately half of the epithelial thickness; 1:1 ratio of pit:gland (Fig. 2.8.1) 3. Scattered endocrine cells present below the surface epithelium including cells that secrete gastrin, somatostatin, and serotonin (enterochromaffin-like) 4. Adjacent to the duodenal mucosa | 1. More loosely packed glands composed of mucinous cells (Fig. 2.8.2) 2. Short pits and short glands span approximately half of the epithelial thickness; 1:1 ratio of pit:gland (Fig. 2.8.2) 3. Scattered endocrine cells present below the surface epithelium including cells that secrete somatostatin and serotonin (enterochromaffin) 4. Adjacent to the esophageal mucosa | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Prognosis | Not applicable | Not applicable |

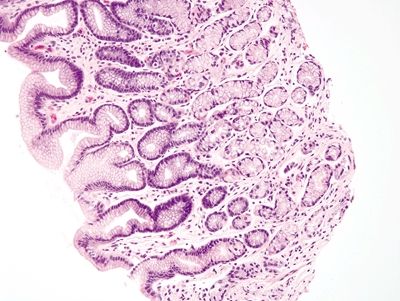

Figure 2.8.1 Antrum architecture composed of short pits and glands in a 1:1 ratio.

Figure 2.8.2 Cardia architecture composed of short pits and glands in a 1:1 ratio.

2.9 Watermelon stomach (gastric antral vascular ectasia) vs. Chemical gastropathy

| Watermelon Stomach (Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia) | Chemical Gastropathy | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Typically elderly (mean age 70); predominantly females (75%) | Typically adults; no gender predominance |

| Location | Predominantly antrum | Predominantly antrum |

| Symptoms | Both acute and chronic GI bleeding presents as light-headedness, dizziness, fatigue, hematemesis, hematochezia | Nonspecific epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting; severe disease can present with GI bleeding and acute achy pain related to ulcers |

| Signs | Due to chronic blood loss, iron deficiency anemia, heme-positive stool, melena; endoscopy shows classic appearance of red linear stripes at the peak of mucosal folds radiating to the pylorus like “stripes of watermelon” | Few, if any |

| Etiology | Associated with autoimmune and connective tissue diseases; some cases have been associated with antral prolapse | Chemical-induced injury due most commonly to NSAID use, as well as bile reflux in patients with a history of antrectomy or functional gastric disorders. Other risk factors include anticonvulsant and chemotherapeutic drugs |

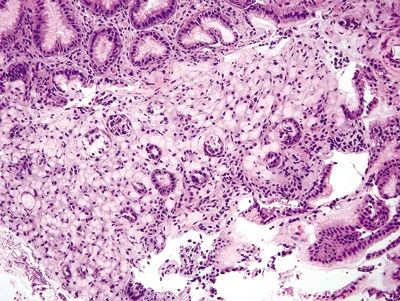

| Histology | ||

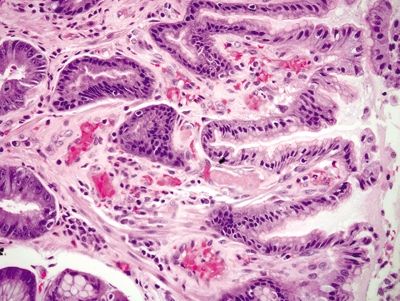

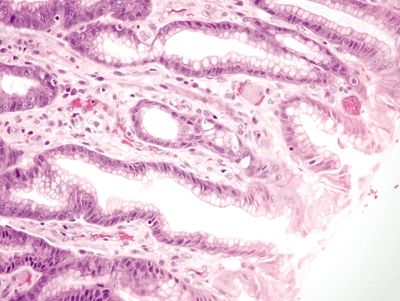

| 1. Foveolar hyperplasia with dilated mucosal capillaries and fibromuscular hypertrophy of the lamina propria (Figs. 2.9.1, 2.9.2, and 2.9.5) 2. Intraluminal fibrin thrombi (corresponding to the characteristic linear vascular stripes at the tips of the mucosal folds radiating from the pylorus seen endoscopically) (Figs. 2.9.2–2.9.4) 3. Minimal to no inflammation | 1. Reactive mucosal changes including marked hyperplasia of the foveolar epithelium resulting in increased pit length (“corkscrewing”), focal loss of mucin, lamina propria edema, smooth muscle proliferation in the lamina propria, and vascular congestion (Figs. 2.9.6 and 2.9.7) 2. No fibrin thrombi (Fig. 2.9.8) 3. Minimal inflammation; rare acute inflammation can be present in association with erosions or ulcers (Figs. 2.9.9 and 2.9.10) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Varies depending on the severity of disease; mild cases are managed with iron supplementation and blood transfusion as needed, while more severe cases require endoscopic vascular ablation or surgical antrectomy | Antacid therapy with proton pump inhibitors and discontinuation of any relevant medications |

| Prognosis | Endoscopic ablation is very effective; surgical therapy is definitive but has a much higher risk of mortality | Excellent; benign |

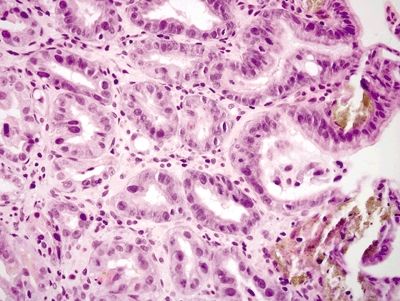

Figure 2.9.1 Watermelon stomach. Foveolar hyperplasia.

Figure 2.9.2 Watermelon stomach. Foveolar hyperplasia, proliferation of lamina propria smooth muscle, and fibrin thrombi (center).

Figure 2.9.3 Watermelon stomach. Intravascular fibrin thrombi.

Figure 2.9.4 Watermelon stomach. Intravascular fibrin thrombi (upper right).

Figure 2.9.5 Watermelon stomach. Fibromuscular hypertrophy of the lamina propria.

Figure 2.9.6 Chemical gastropathy. Foveolar hyperplasia of glands with a “corkscrew” appearance.

Figure 2.9.7 Chemical gastropathy. Marked reactive epithelial changes.

Figure 2.9.8 Chemical gastropathy. Foveolar hyperplasia with no vascular or muscular changes.

Figure 2.9.9 Chemical gastropathy. Mucosal ulceration with mixed acute and chronic inflammation.

Figure 2.9.10 Chemical gastropathy. Mixed acute and chronic inflammation.

2.10 Mucosal calcinosis vs. Parasitic gastritis

| Mucosal Calcinosis | Parasitic Gastritis | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Typically adults; female predominance | Any age; male = female |

| Location | Antrum and body; superficial mucosa beneath the surface foveolar epithelium | Any location |

| Symptoms | Nonspecific; symptoms related to predisposing underlying disease | Nonspecific epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, fatigue |

| Signs | None | Few; some present with nutritional deficiencies and serum IgE is often elevated |

| Etiology | Most commonly due to the deposition of calcium related to tertiary hyperparathyroidism of renal failure. Patients with renal failure most commonly have hypocalcemia due to disordered calcium metabolism. They also develop hyperphosphatemia as well as low vitamin D levels, all of which result in increased PTH secretion by the parathyroid glands (tertiary hyperparathyroidism). This marked increase in PTH increases both calcium and phosphate absorption subsequently resulting in hypercalcemia with deposition of calcium in various organs. Mucosal calcinosis has also been associated with atrophic gastritis, hypervitaminosis A, organ transplantation, gastric neoplasia, uremia, citrate-containing blood products, isotretinoin, and sucralfate | Infectious gastritis most often seen in immunosuppressed patients; common infections include Strongyloidiasis and schistosomiasis, which are rarely seen in the stomach |

| Histology | ||

| 1. Irregular, amorphous basophilic deposits present in the superficial mucosa beneath the foveolar tips, which are slightly refractile and do not polarize (Fig. 2.10.1) 2. Deposits lack internal structure (Fig. 2.10.2) 3. No eosinophils or Charcot-Leyden crystals | 1. Strongyloides: All stages (e.g., larva, egg, adult) of worm embedded in gastric pits with background crypt hyperplasia and marked mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils (Fig. 2.10.3) 2. Schistosomiasis: Ulcerate and edematous mucosa with Schistosoma ova within the lamina propria associated with prominent eosinophils and occasionally giant cells. Eggs are deeply basophilic and oval shaped with a lateral spine (Fig. 2.10.4) 3. Prominent eosinophils and Charcot-Leyden crystals are common (Fig. 2.10.5) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Nonspecific; patients are treated for any underlying disease | Antiparasitic therapy |

| Prognosis | Variable, nonspecific—mucosal calcinosis is considered an incidental finding; prognosis is determined by the extent of systemic calcinosis and the severity of renal failure and/or other underlying disease | Generally good; most cases resolve with treatment. There is a rare risk of complications including perforation, and some develop dysplasia and/or carcinoma presumably due to chronic irritation. |

Figure 2.10.1 Mucosal calcinosis.

Figure 2.10.2 Mucosal calcinosis.

Figure 2.10.3 Strongyloides organisms at various life stages in colonic crypts.

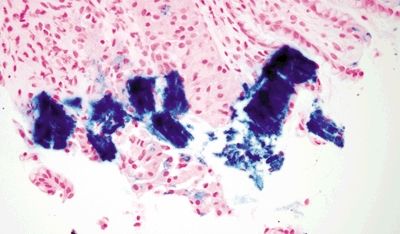

Figure 2.10.4 Schistosomiasis. The ova are uniform structures.

Figure 2.10.5 Parasitic infestation. There are numerous eosinophils in the field.

2.11 Proton pump inhibitor effect vs. Fundic gland polyp and oxyntic gland polyp

| Proton Pump Inhibitor Effect | Fundic Gland Polyp and Oxyntic Gland Polyp | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Typically adults; no gender predominance | Typically adults (sporadic, mean age 50s; familial, mean age 20s); female predominance (familial forms show no gender predominance) |

| Location | Fundus | Fundic gland polyp: body and fundus; oxyntic gland polyp: body and cardia |

| Symptoms | Nonspecific, unrelated to the finding; symptoms may reflect underlying disease that necessitated proton pump inhibitor therapy | Generally asymptomatic; nonspecific abdominal pain is most common |

| Signs | Few, if any. Endoscopy usually negative for polyps | Few, if any. Endoscopy usually shows multiple small, sessile, hemispherical polyps occurring in clusters sometimes |

| Etiology | Proton pump inhibitors inhibit the H/K ATPase ion channel that maintains the acidic pH of the gastric lumen, which consequently activates feedback mechanisms (i.e., increased secretion of gastrin) in an attempt to increase acid secretion and normalize the pH. Gastrin stimulates parietal cell growth resulting in the cytologic changes of the proton pump inhibitor effect. Use of proton pump inhibitors is not necessary to see this effect; it is present in patients with no known history of PPI use | Fundic gland polyp: Most common type of gastric polyp, which is either familial or sporadic; familial lesions are associated with familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome Oxyntic gland polyp: Rare polyp of unknown etiology |

| Histology | ||

| 1. Hyperplastic parietal cells with apocrine-like changes including cytoplasmic swelling, vacuolated cytoplasm, and apical blebbing (Figs. 2.11.1–2.11.3) | Fundic gland polyp: 1. Random, disordered proliferation of oxyntic mucosa with dilated fundic glands and/or microcysts lined by flattened oxyntic epithelium (Figs. 2.11.4–2.11.6) 2. Background gastric mucosa is normal Oxyntic gland polyp: 1. Irregularly branched tubules arranged in anastomosing cords (Fig. 2.11.7) 2. Tubules composed of monomorphous epithelial cells with small, central, round nuclei and ample amphophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 2.11.8) 3. Scattered intermixed parietal cells 4.Normal background mucosa | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Nonspecific; related to any other pathology present in the specimen | Fundic gland polyp: Most lesions regress. Polypectomy for larger lesions Oxyntic gland adenoma: Complete polypectomy |

| Prognosis | Variable, nonspecific, incidental finding; prognosis related to any other pathology present in the specimen | Excellent; generally considered benign lesions. |

Figure 2.11.1 Proton pulp inhibitor effect. Hyperplastic glands of proton pump inhibitor effect.

Figure 2.11.2 Proton pulp inhibitor effect. Apical blebbing of proton pump inhibitor effect.

Figure 2.11.3 Proton pulp inhibitor effect. Cytoplasmic vacuolization of proton pump inhibitor effect.

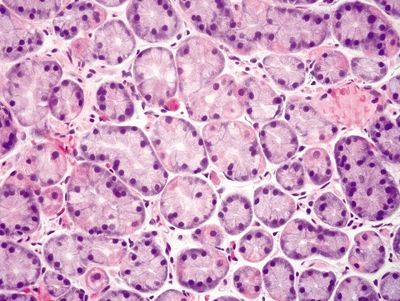

Figure 2.11.4 Fundic gland polyp.

Figure 2.11.5 Fundic gland polyp. Focal cystically dilated glands.

Figure 2.11.6 Fundic gland polyp. Cystically dilated glands lined by flattened oxyntic epithelium.

Figure 2.11.7 Oxyntic gland adenoma. Irregular branching tubules arranged in cords.

Figure 2.11.8 Oxyntic gland adenoma. Monomorphous cells with prominent apical eosinophilic cytoplasm.

2.12 Iron pill gastritis vs. Gastric siderosis

| Iron Pill Gastritis | Gastric Siderosis | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Any age; predominantly female | Typically adults; no gender predominance |

| Location | Any part of the stomach | Predominantly antrum and fundus |

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, vomiting, and some present with GI bleeding | Related to underlying disorder, patients with hemochromatosis may present with symptoms of diffuse iron overload including cirrhosis, diabetes, and joint pain while those with secondary iron overload generally present with symptoms of anemia |

| Signs | None; patient may have a history of iron deficiency anemia | Related to underlying disorder; clinical lab tests will show increased ferritin |

| Etiology | Unknown, likely related to concentration-dependent chemical toxicity of iron and its metabolites; up to 50% of patients have comorbid conditions that predispose them to gastric injury | Iron deposition due to either primary iron overload related to hemochromatosis or secondary iron overload associated with chronic blood transfusion, cirrhosis, and supplemental iron |

| Histology | ||

| 1. Mucosal erosion with associated acute and chronic inflammation, granulation tissue, and/or necrosis (Fig. 2.12.1) 2. Reactive epithelial changes consisting of enlarged nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Fig. 2.12.2) 3. Iron deposition within the lamina propria and surface epithelium (Fig. 2.12.1) | 1. Few mucosal changes 2. Iron deposition in deep glands of the antrum and fundus (Figs. 2.12.4 and 2.12.5) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Symptomatic treatment; supplement with liquid iron | Variable, depending on underlying disorder |

| Prognosis | Good; symptoms usually resolve quickly | Variable; it suggests a diagnosis of hemochromatosis that can be associated with morbidity related to iron deposition in other organs |

Figure 2.12.1 Iron pill gastritis. Mucosal erosion and iron deposition.

Figure 2.12.2 Iron pill gastritis. Reactive changes of iron pill gastritis.

Figure 2.12.3 Iron pill gastritis. Iron stain highlighting iron within the superficial mucosa.

Figure 2.12.4 Gastric siderosis. Iron deposition in the lower half of the epithelium.

Figure 2.12.5 Gastric siderosis. Iron deposition in the deep glands.

Figure 2.12.6 Gastric siderosis. Iron stain highlighting iron deposition limited to the deep mucosa.

2.13 Colchicine and taxol–associated gastropathy vs. Dysplasia

| Colchicine and Taxol–Associated Gastropathy | Dysplasia | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Typically adults; no gender predominance | Typically adults; predominantly males 50s–70s |

| Location | Colchicine: Antrum and duodenum; sparing of the gastric body Taxol: Any location | Any location |

| Symptom | Nonspecific abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, otherwise related to underlying disease | No specific symptoms, unless associated with invasive disease (abdominal pain, early satiety, gastric reflux) |

| Signs | Related to underlying disease | No specific signs |

| Etiology | Colchicine: Injury related to colchicine toxicity, an antimitotic drug used primarily in the treatment of gout. Colchicine at therapeutic levels causes no injury, but patients with renal failure can develop colchicine toxicity due to impaired drug clearance | Precancerous lesion associated with history of chronic Helicobacter infection and autoimmune atrophic gastritis and familial adenomatous polyposis |

| Taxol: Nontoxic pattern of injury due to Taxol, an antimitotic drug used in the treatment of various malignancies. Taxol effect is seen at both therapeutic and toxic drug levels | ||

| Histology | ||

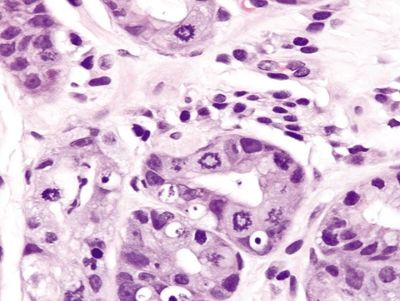

| Colchicine: 1. Epithelial changes including nuclear pseudostratification with subsequent loss of nuclear polarity (Fig. 2.13.1) 2. Metaphase ring mitoses (Fig. 2.13.2) 3. Apoptotic bodies in the proliferative compartment (between the pits and surface). (Fig. 2.13.3) Taxol: 1. Marked epithelial changes including loss of nuclear polarity, diffuse loss of mucin, and hyperchromasia (Fig. 2.13.4) 2. Epithelial changes prominent at the base of the crypts, do not extend to the surface—limited to the proliferative compartment (Fig. 2.13.5) 3. Mitotic arrest associated with ring mitoses, and marked apoptosis (Figs. 2.13.6 and 2.13.7) 4. Background mucosa with cell necrosis and multifocal ulceration | 1. Low-grade dysplasia characterized by hyperchromatic, elongated, pseudostratified nuclei and nuclear crowding (Figs. 2.13.7 and 2.13.8) 2. High-grade dysplasia shows loss of nuclear polarity, glandular crowding, and cribriform glands (Fig. 2.13.9) 3. Epithelial changes and mitoses involve the base of crypts, extending to the surface mucosa (Fig. 2.13.9) 4. Most lesions associated with background intestinal metaplasia | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Colchicine: Immediate discontinuation of the offending drug Taxol: Generally none, continue therapy | If polypoid, removal of polyp; for polypoid and flat dysplasia, repeat biopsy with representative sampling of the entire stomach to evaluate for invasive disease |

| Prognosis | Colchicine: Potentially fatal due to similar effects in other organs resulting in multiorgan failure; early diagnosis is critical Taxol: Related to the underlying disorder for which the drug is being administered | Variable; low-grade dysplasia can regress spontaneously, while high-grade dysplasia usually persists and can progress to invasive carcinoma |

Figure 2.13.1 Colchicine toxicity. Nuclear pseudostratification and loss of polarity.

Figure 2.13.2 Colchicine toxicity. Prominent ring mitoses.

Figure 2.13.3 Colchicine toxicity. Apoptotic bodies in the proliferative compartment.

Figure 2.13.4 Taxane effect. Reactive epithelial changes including focal loss of mucin and nuclear pseudostratification. The surface is uninvolved.

Figure 2.13.5 Taxane effect. Epithelial changes predominant in the proliferative compartment.

Figure 2.13.6 Taxane effect. Ring mitoses and apoptotic bodies.