Appendix

5.1 Granulomatous appendicitis vs. Crohn disease of the appendix

5.2 Interval appendix vs. Crohn disease of the appendix

5.3 Infectious appendicitis with granulomas vs. Crohn disease of the appendix

5.4 Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm vs. Appendiceal diverticulum

5.5 Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm vs. Sessile serrated adenoma

5.6 Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm vs. Tubular/tubulovillous adenoma

5.7 Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm vs. Well-differentiated adenocarcinoma

5.8 Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm vs. High-grade mucinous neoplasm

5.9 Well-differentiated neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumor vs. Goblet cell carcinoid

5.10 Tubular carcinoid vs. Adenocarcinoma

5.11 Goblet cell carcinoid vs. Adenocarcinoma ex goblet cell carcinoid

5.1 Granulomatous appendicitis vs. Crohn disease of the appendix

| Granulomatous Appendicitis | Crohn Disease of the Appendix | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Typically young adults; more common in males | Typically young adults (20s–30s); no gender predominance |

| Location | Any location | Any location |

| Symptoms | Right lower quadrant abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite | Depends on site of involvement; usually present with abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, dyspepsia, weight loss |

| Signs | Abdominal tenderness, elevated white blood cell count, fever | Depends on severity of underlying Crohn disease, including anemia and failure to thrive. CT scan shows mural thickening extending from the appendix into the ileum and/or cecum |

| Etiology | Unknown; some cases have been associated with Yersinia infection; other associations include foreign body reactions, interval appendicitis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Enterobius vermicularis, and sarcoidosis | Unknown; chronic relapsing and remitting inflammatory disease, which can affect any segment of the GI tract but commonly involves the terminal ileum and proximal colon |

| Histology | ||

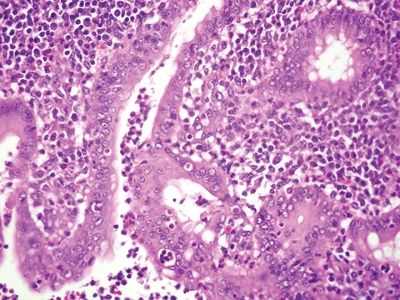

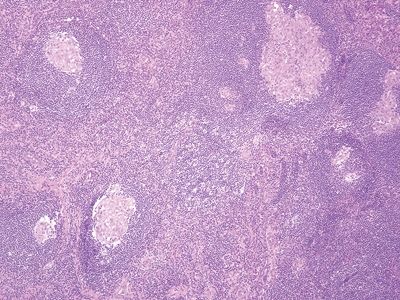

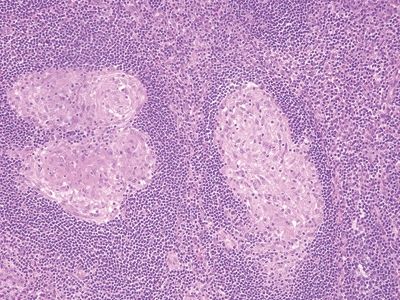

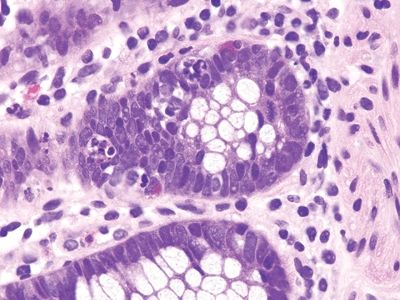

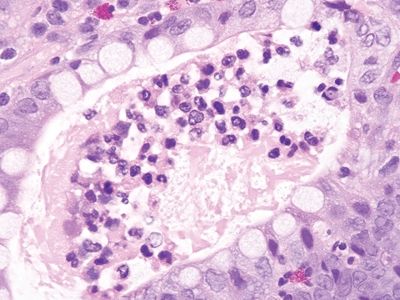

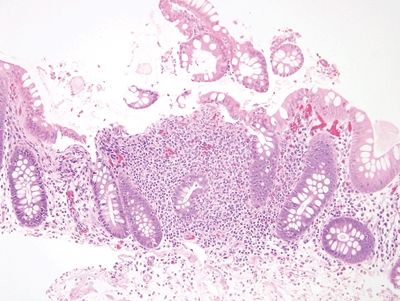

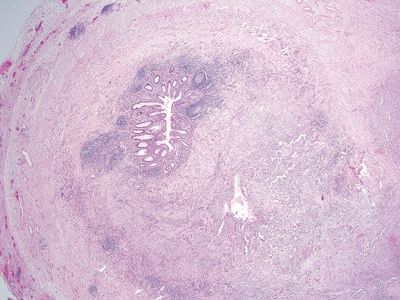

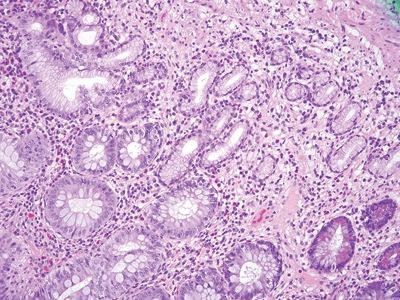

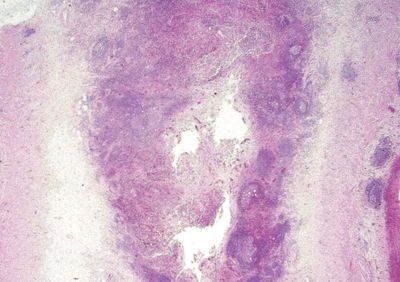

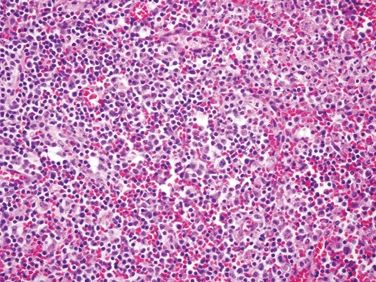

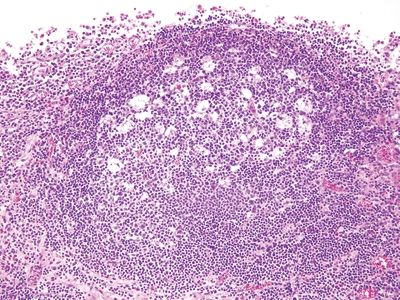

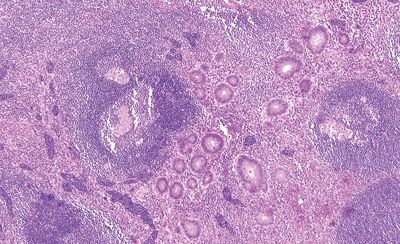

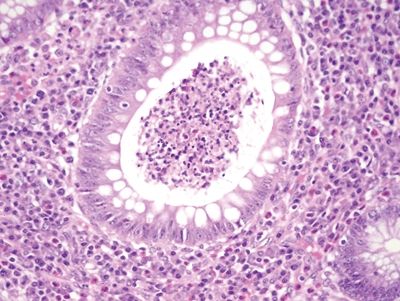

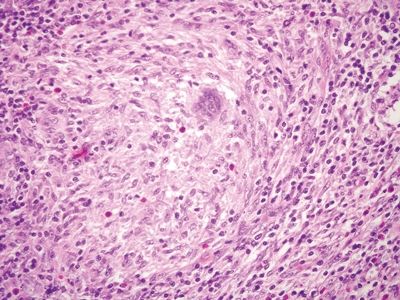

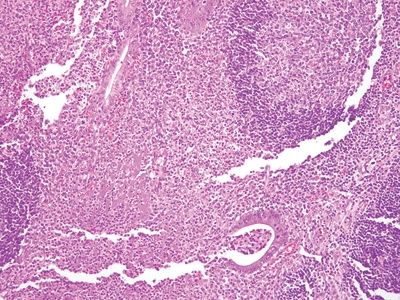

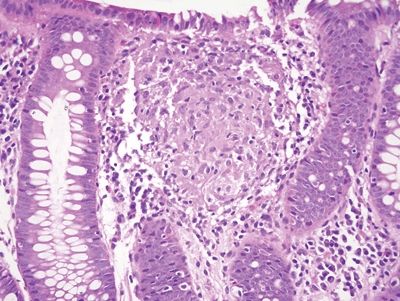

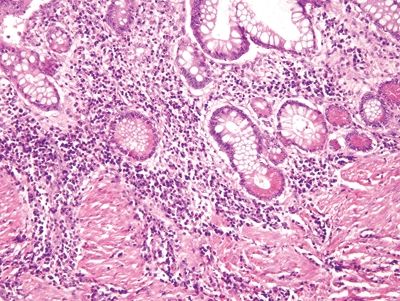

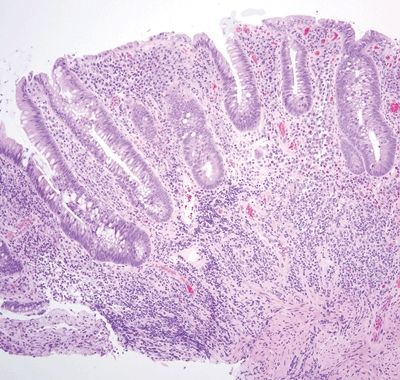

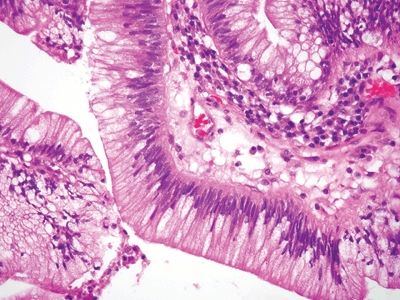

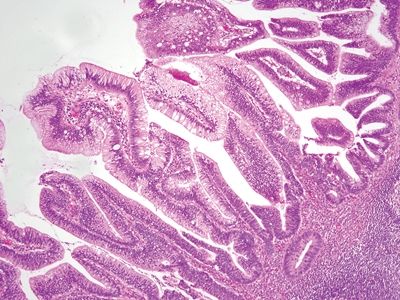

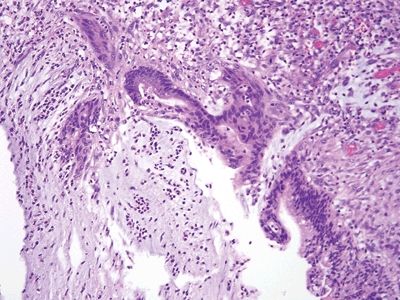

| 1. Foci of inflammation characterized by neutrophils within the epithelium (cryptitis) and crypts (crypt abscesses) (Fig. 5.1.1) 2. Transmural lymphoid aggregates 3. Numerous (Fig. 5.1.2) well-formed granulomas (Fig. 5.1.3)—20 granulomas per tissue section 4. Few chronic changes, if any 5. Occasional fissures and fistulae | 1. Discrete foci of inflammation characterized by neutrophils within the epithelium (cryptitis) (Fig. 5.1.4) and crypts (crypt abscesses) (Fig. 5.1.5) adjacent to normal epithelium (“skip lesions”—variability of inflammation along the GI tract) 2. Aphthous ulcers characterized by focal epithelial necrosis associated with a mixed acute and chronic inflammatory infiltrate and an underlying lymphoid aggregate (Fig. 5.1.6) 3. Prominent submucosal chronic inflammation 4. Transmural lymphoid aggregates arranged in a “string of pearls” (Fig. 5.1.7) 5. Only occasional poorly formed granulomas—0.3 granulomas per tissue section (Fig. 5.1.8) 6. Chronic changes include pyloric metaplasia (Fig. 5.1.9) and crypt distortion (Fig. 5.1.10) 7. Fissures, fistulae, and longitudinal ulcers are common | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Appendectomy is generally definitive therapy | The primary treatment is immunomodulation with a variety of agents including steroids and TNF-alpha inhibitors. Surgical resection for severe complications including obstruction or hemorrhage |

| Prognosis | Very good; few patients have recurrent disease though a subset are later diagnosed with Crohn disease | Variable; related to the extent and severity of the underlying Crohn disease. Appendiceal involvement usually indicates extensive ileocolic disease and thus is associated with more severe disease and a worse prognosis |

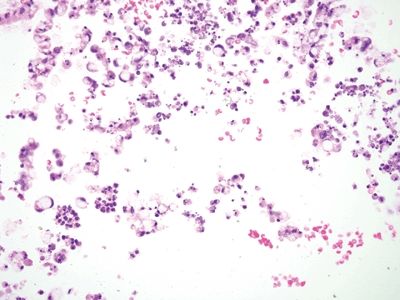

Figure 5.1.1 Granulomatous appendicitis. Focal cryptitis with infiltrating neutrophils.

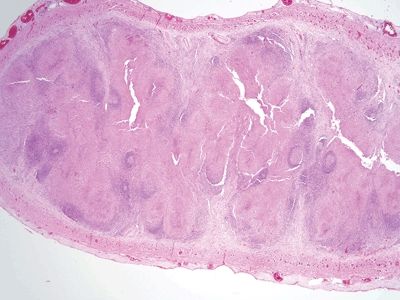

Figure 5.1.2 Granulomatous appendicitis. Transmural granulomatous inflammation.

Figure 5.1.3 Granulomatous appendicitis. Well-formed noncaseating granulomas.

Figure 5.1.4 Cryptitis in Crohn colitis.

Figure 5.1.5 Crypt abscess in Crohn colitis.

Figure 5.1.6 Aphthous ulcer consisting of a mucosal lymphoid aggregate with a surface erosion.

Figure 5.1.7 Transmural lymphoid aggregates in Crohn colitis.

Figure 5.1.8 Crohns appendicitis. Rare poorly formed granuloma.

Figure 5.1.9 Pyloric metaplasia in Crohn appendicitis.

Figure 5.1.10 Crypt distortion in Crohn appendicitis.

5.2 Interval appendix vs. Crohn disease of the appendix

| Interval Appendix | Crohn Disease of the Appendix | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Children to early adults (5–20 years); male predominance | Typically young adults (20s –30s); no gender predominance |

| Location | Any location | Any location |

| Symptoms | Acute right lower quadrant abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting | Depends on site of involvement, usually present with abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, dyspepsia, weight loss |

| Signs | Fever, elevated white blood cell count, abdominal tenderness, rebound tenderness | Depends on severity of underlying Crohn disease, including anemia and failure to thrive. CT scan shows mural thickening extending from the appendix into the ileum and/or cecum |

| Etiology | Chronic reparative response to ruptured acute appendicitis, which is usually treated with antibiotic therapy prior to appendectomy several weeks later | Unknown; chronic relapsing and remitting inflammatory disease, which can affect any segment of the GI tract but commonly involves the terminal ileum and proximal colon |

| Histology | ||

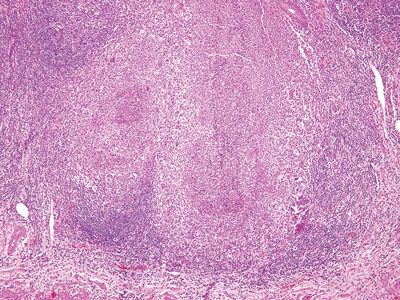

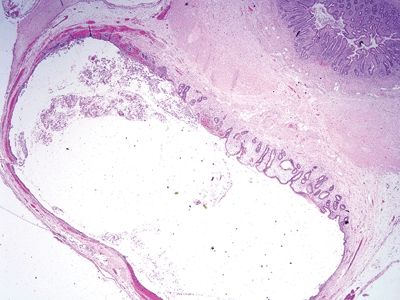

| Two histologic patterns: 1. Usual pattern a. Transmural acute and chronic inflammation (Figs. 5.2.1 and 5.2.2) b. Foreign body giant cells c. Granulation tissue and hemosiderin deposition (Fig. 5.2.3) d. Moderate serosal fibrosis and serositis e. Transmural mucin extrusion 2. Xanthogranulomatous pattern a. Foam cells b. Scattered multinucleated histiocytes c. Hemosiderin deposition d. Luminal obliteration with sparing of lymphoid follicles (Figs. 5.2.1 and 5.2.4) 3. Up to two-thirds of cases have prominent granulomas (Fig. 5.2.5) 4. No fissures | 1. Transmural lymphoid aggregates arranged in a “string of pearls” (Fig. 5.2.6) 2. Discrete foci of inflammation characterized by neutrophils within the epithelium (cryptitis) (Fig. 5.2.7) and crypts (crypt abscesses) (Fig. 5.2.8) adjacent to normal epithelium (“skip lesions”—variability of inflammation along the GI tract) 3. Only occasional poorly formed granulomas—0.3 granulomas per tissue section (Fig. 5.2.9) 4. Fissures, fistulae, and longitudinal ulcers are common 5. Dense concentric fibrosis of the subserosa | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Surgical resection with supportive care and antibiotic therapy | The primary treatment is immunomodulation with a variety of agents including steroids and TNF-alpha inhibitors. Surgical resection for severe complications including obstruction or hemorrhage |

| Prognosis | Very good; complications are rare and most commonly associated with rupture | Variable; related to the extent and severity of the underlying Crohn disease. Appendiceal involvement usually indicates extensive ileocolic disease and thus is associated with more severe disease and a worse prognosis |

Figure 5.2.1 Transmural acute and chronic inflammation with luminal obliteration and sparing of lymphoid follicles in interval appendicitis. Note the linear arrangement of lymphoid aggregates in the serosa at the right part of the field.

Figure 5.2.2 Mixed acute and chronic inflammation in interval appendicitis.

Figure 5.2.3 Granulation tissue in interval appendicitis.

Figure 5.2.4 Interval appendix. Reactive follicle with prominent germinal center.

Figure 5.2.5 Prominent transmural granulomatous inflammation in interval appendicitis.

Figure 5.2.6 Transmural chronic inflammation and lymphoid aggregates in Crohn appendicitis.

Figure 5.2.7 Focal cryptitis in Crohn appendicitis.

Figure 5.2.8 Crypt abscess in Crohn appendicitis.

Figure 5.2.9 Rare poorly formed granuloma in Crohn appendicitis.

5.3 Infectious appendicitis with granulomas vs. Crohn disease of the appendix

| Infectious Appendicitis with Granulomas | Crohn Disease of the Appendix | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Any age; male = female | Typically young adults (20s–30s); no gender predominance |

| Location | Any location | Any location |

| Symptoms | Nonspecific abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, fatigue, weight loss, GI bleeding | Depends on the site of involvement; usually present with abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, dyspepsia, weight loss |

| Signs | Abdominal tenderness, fever | Depends on severity of underlying Crohn disease, including anemia and failure to thrive. CT scan shows mural thickening extending from the appendix into the ileum and/or cecum |

| Etiology | Granulomatous response associated with certain infections including Mycobacteria sp., Yersinia sp., and fungal infections such as Histoplasma capsulatum | Unknown; chronic relapsing and remitting inflammatory disease, which can affect any segment of the GI tract but commonly involves the terminal ileum and proximal colon |

| Histology | ||

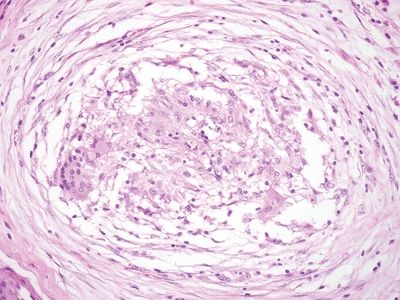

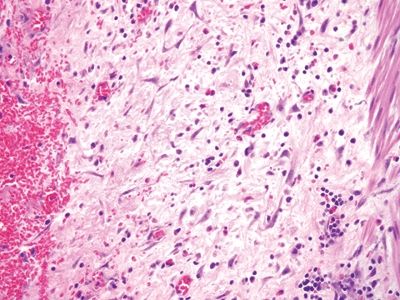

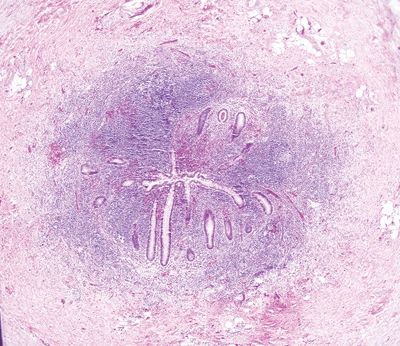

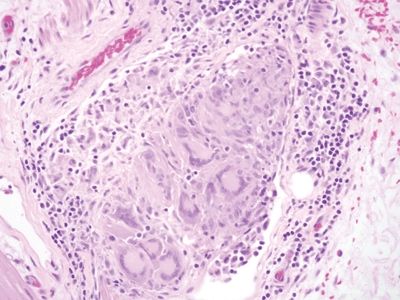

| 1. Background often shows marked acute and chronic inflammation primarily involving the lamina propria with focal erosion and/or ulceration (Fig. 5.3.1) 2. Numerous, large, well-formed, often necrotizing granulomas (Fig. 5.3.2) 3. Granulomas often centered within lymphoid follicles (Fig. 5.3.3) 4. Multinucleated Langhans-type giant cells occasionally present (Fig. 5.3.4) 5. Bowel wall thickening and ulceration can be seen particularly in Yersinia infection 6. No significant crypt distortion; plasma cells are not increased | 1. Discrete foci of inflammation characterized by neutrophils within the epithelium (cryptitis) (Fig. 5.3.5) and crypts (crypt abscesses) (Fig. 5.3.6) adjacent to normal epithelium (“skip lesions”—variability of inflammation along the GI tract) 2. Only rare occasional poorly formed, nonnecrotizing granulomas (Fig. 5.3.7) 3. Granulomas randomly distributed; no association with lymphoid follicles (Fig. 5.3.7) 4. No multinucleated giant cells 5. Dense concentric fibrosis of the subserosa 6. Background shows chronic changes including basal plasmacytosis (Fig. 5.3.8) and crypt distortion (Fig. 5.3.9) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Supportive care and/or antibiotics. Surgery for complications including perforation and obstruction | The primary treatment is immunomodulation with a variety of agents including steroids and TNF-alpha inhibitors. Surgical resection for severe complications including obstruction or hemorrhage |

| Prognosis | Generally good; most infections resolve spontaneously or with antibiotic therapy | Variable; related to the extent and severity of the underlying Crohn disease. Appendiceal involvement usually indicates extensive ileocolic disease and thus is associated with more severe disease and a worse prognosis |

Figure 5.3.1 Marked acute and chronic inflammation in infectious appendicitis.

Figure 5.3.2 Multiple, large necrotizing granulomas in Yersinia infectious appendicitis.

Figure 5.3.3 Obliteration of the appendiceal mucosa and lumen by large, coalescent necrotizing granulomas centered within lymphoid follicles in Yersinia infectious appendicitis.

Figure 5.3.4 Prominent Langhans-type giant cells in infectious appendicitis.

Figure 5.3.5 Focal cryptitis in Crohn appendicitis.

Figure 5.3.6 Crypt abscess in Crohn appendicitis.

Figure 5.3.7 Poorly formed Granuloma in Crohn appendicitis.

Figure 5.3.8 Basal plasmacytosis in Crohn disease.

Figure 5.3.9 Crypt distortion and marked mucosal chronic inflammation with an associated lymphoid aggregate in Crohn appendicitis.

5.4 Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm vs. Appendiceal diverticulum

| Low-Grade Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm | Appendiceal Diverticulum | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Typically adults (60s); female predominance | Typically adults (50s –60s); no gender predominance |

| Location | Any location in appendix | Any location in appendix |

| Symptoms | Most patients are symptomatic and present with right lower quadrant pain. Occasionally, patients present with abdominal distension due to rupture and subsequent extrusion of mucus into the peritoneal cavity (pseudomyxoma peritonei) | Most are asymptomatic and discovered either incidentally or in association with acute appendicitis |

| Signs | Abdominal tenderness, dullness to abdominal percussion | Nonspecific, vague abdominal pain; nausea |

| Etiology | Unknown; most common mucinous neoplasm of the appendix. Some cases are associated with colonic adenomas | Unknown; usually an acquired defect thought to be due to wall weakness and increased intraluminal pressure; associated with cystic fibrosis; up to 14% of patients develop diverticula and can be markers of local or regional neoplasms including low-grade epithelial neoplasms of the appendix |

| Histology | ||

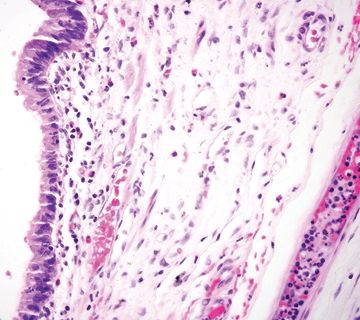

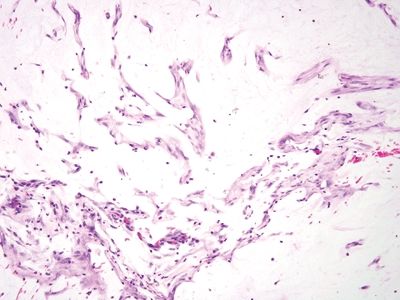

| 1. Flat to villiform intestinal-type epithelium lined by basally located to pseudostratified elongated and hyperchromatic nuclei with prominent apical mucin (Fig. 5.4.1) 2. Up to 42% are associated with diverticula periappendiceal serosal mucin deposits 3. Back-to-back crypts with minimal intervening lamina propria (Fig. 5.4.2) 4. No association with neuromas and few regenerative changes other than those associated with extruded mucin | 1. Usually, multiple diverticula, <5 mm 2. Herniation of the mucosa and muscularis mucosae through the submucosa and muscularis propria longitudinally parallel to vessels (Figs. 5.4.3 and 5.4.4) 3. Free-floating periappendiceal mucin, which can be associated with eversion of the diverticular epithelium onto the serosal surface mimicking serosal involvement by tumor (Figs. 5.4.5 and 5.4.6) 4. Preserved architecture—background mucosa is hyperplastic with focal villous architecture, mild reactive atypia (Fig. 5.4.7), and crypt distortion, and the changes are most prominent in the superficial mucosa sparing the crypts 5. Often associated with mucosal neuromas and other reparative changes | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Primary treatment is surgical excision | Appendectomy is curative; standard therapy or any underlying neoplasm identified |

| Prognosis | Generally good; limited disease is considered clinically benign. Clinical history of pseudomyxoma peritonei portends a worse outcome. Five-year survival rate for tumors with spread beyond the appendix is 86% | Excellent; nearly universally benign. The prognosis of cases associated with cystic fibrosis or neoplasm varies depending on the extent of the underlying pathology |

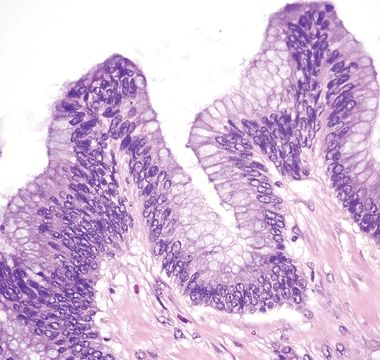

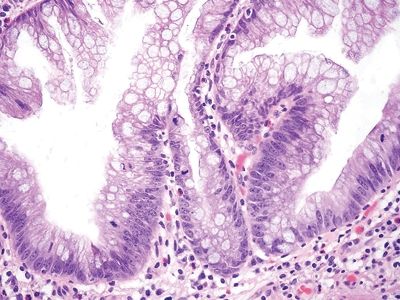

Figure 5.4.1 Low-grade dysplasia in low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm characterized by elongated, hyperchromatic pseudostratified nuclei.

Figure 5.4.2 Proliferative epithelium of low-grade mucinous neoplasm with minimal intervening lamina propria.

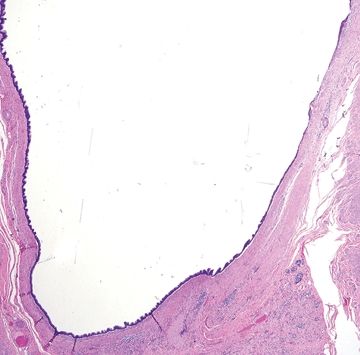

Figure 5.4.3 Diverticulum herniating through the bowel wall.

Figure 5.4.4 Flat epithelium in appendiceal diverticulum with submucosal edema.

Figure 5.4.5 Extruded mucin without epithelial cells.

Figure 5.4.6 Ruptured diverticulum with mucin extrusion and mucous cells.

Figure 5.4.7 Reactive epithelial changes in appendiceal diverticulum.

5.5 Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm vs. Sessile serrated adenoma

| Low-Grade Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm | Sessile Serrated Adenoma | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Typically adults (60s); female predominance | Adults (60s); no gender predominance |

| Location | Any location in the appendix; typically involves the entire luminal circumferences | Typically involve the entire luminal circumference |

| Symptoms | Most patients are symptomatic and present with right lower quadrant pain. Occasionally, patients present with abdominal distension due to rupture and subsequent extrusion of mucus into the peritoneal cavity (pseudomyxoma peritonei) | |

| Signs | Abdominal tenderness, dullness to abdominal percussion | Few, if any |

| Etiology | Unknown; most common mucinous neoplasm of the appendix. Some cases are associated with colonic adenomas | Unknown; a subset have loss of microsatellite instability and mutations in BRAF (29%) and KRAS (34%) though the biologic significance of these mutations is unknown (19%) |

| Histology | ||

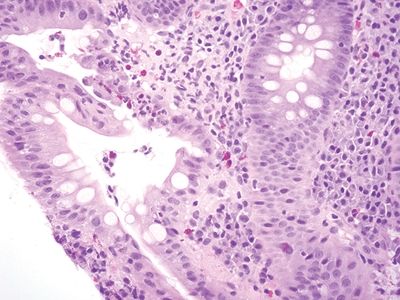

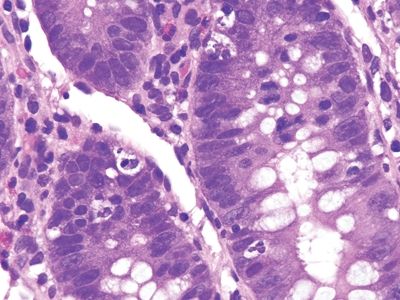

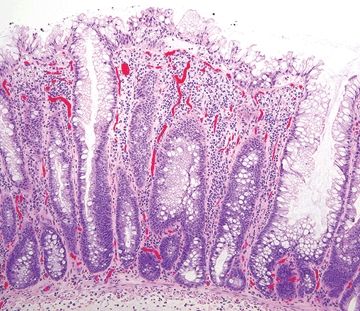

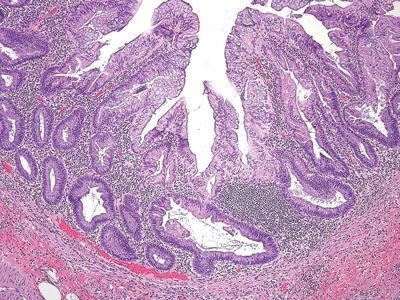

| 1. Flat to villiform intestinal-type epithelium lined by basally located to pseudostratified elongated and hyperchromatic nuclei with prominent apical mucin (Figs. 5.5.1 and 5.5.2) 2. Mucous cells present at the tips of villi form structures 3. Mild to moderate cytologic atypia present (Fig. 5.5.3) 4. Back-to-back crypts with minimal to no intervening lamina propria | 1. Prominent architectural distortion characterized by serrated crypts, which extend toward the crypt base; crypt dilation; crypt branching with transverse-lying/lateral branching crypts at the base (“duck feet”) (Figs. 5.5.4 and 5.5.5) 2. Differentiated mucous cells located at the crypt base (Fig. 5.5.6) 3. No to minimal cytologic atypia in early lesions; late lesions can show moderate cytologic atypia 4. Villiform architecture is not prominent | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Primary treatment is surgical excision | Surgical resection; appendectomy is usually curative. Routine colonoscopy is recommended |

| Prognosis | Generally good; limited disease is considered clinically benign. Clinical history of pseudomyxoma peritonei portends a worse outcome. Five-year survival rate for tumors with spread beyond the appendix is 86% | Generally good, though the malignant potential of SSA in the appendix is still unknown |

Figure 5.5.1 Cystic low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm.

Figure 5.5.2 Undulating epithelium of low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm with low-grade dysplasia. Note the absence of lamina propria.

Figure 5.5.3 Reactive epithelial changes in low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm in association with ulceration and acute inflammation.

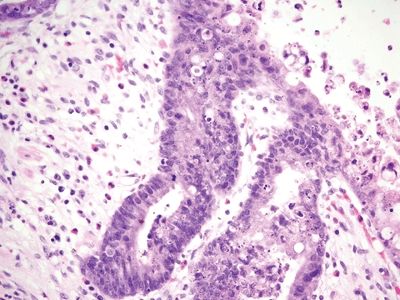

Figure 5.5.4 Sessile serrated adenoma. Serrated epithelium along the entire length of the epithelium.

Figure 5.5.5 Sessile serrated adenoma. Prominent crypt dilation at the base with transverse-lying crypts (“duck feet”).

Figure 5.5.6 Sessile serrated adenoma. Differentiated mucous cells at the crypt base.

5.6 Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm vs. Tubular/tubulovillous adenoma

| Low-Grade Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm | Tubular/Tubulovillous Adenoma | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Typically adults (60s); female predominance | Typically adults (60s); female predominance |

| Location | Any location in appendix; typically involves the entire luminal circumference (Fig. 5.6.1) | Any location in appendix; typically involves the entire luminal circumferences |

| Symptoms | Most patients are symptomatic and present with right lower quadrant pain. Occasionally, patients present with abdominal distension due to rupture and subsequent extrusion of mucus into the peritoneal cavity (pseudomyxoma peritonei) | Most patients are symptomatic and present with right lower quadrant pain. Occasionally, patients present with abdominal distension due to rupture and subsequent extrusion of mucus into the peritoneal cavity (pseudomyxoma peritonei) |

| Signs | Abdominal tenderness, dullness to abdominal percussion | Abdominal tenderness, dullness to abdominal percussion |

| Etiology | Unknown; most common mucinous neoplasm of the appendix. Some cases are associated with colonic adenomas | Unknown; the tumors often have KRAS mutations similar to conventional colon adenomas, but they have not been shown to have mutations in APC, or BRAF |

| Histology | ||

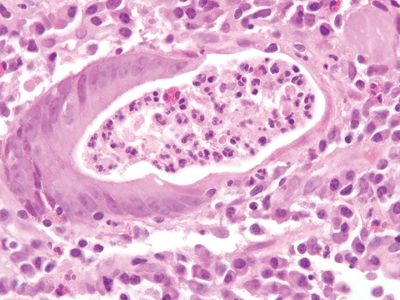

| 1. Flat to villiform intestinal-type epithelium lined by basally located to pseudostratified elongated and hyperchromatic nuclei with prominent apical mucin (Fig. 5.6.2) 2. Often associated with cystic dilation with flatting and partial denudation of the epithelium (Fig. 5.6.3) 3. Variable patterns of invasion including direct extension and extension along diverticula 4. Fibrosis, hyalinization, and calcification of the muscularis propria are common 5. Often present with prominent periappendiceal serosal mucin deposits | 1. Flat to villiform intestinal-type epithelium (Fig. 5.6.4) lined by basally located to pseudostratified elongated and hyperchromatic nuclei with abundant intracytoplasmic mucin (Fig. 5.6.5) 2. Often associated with cystic dilation with flatting and partial denudation of the epithelium 3. No invasion—confined to the mucosa with the muscularis mucosae intact 4. Bowel wall histologically unremarkable 5. No mucin on the peritoneal surface | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Primary treatment is surgical excision | Surgical resection via appendectomy |

| Prognosis | Generally good; limited disease is considered clinically benign. Clinical history of pseudomyxoma peritonei portends a worse outcome and requires close clinical follow-up. Five-year survival rate for tumors with spread beyond the appendix is 86% | Excellent; clinically benign |