Specific Infections of the Genitourinary Tract: Introduction

Tuberculosis

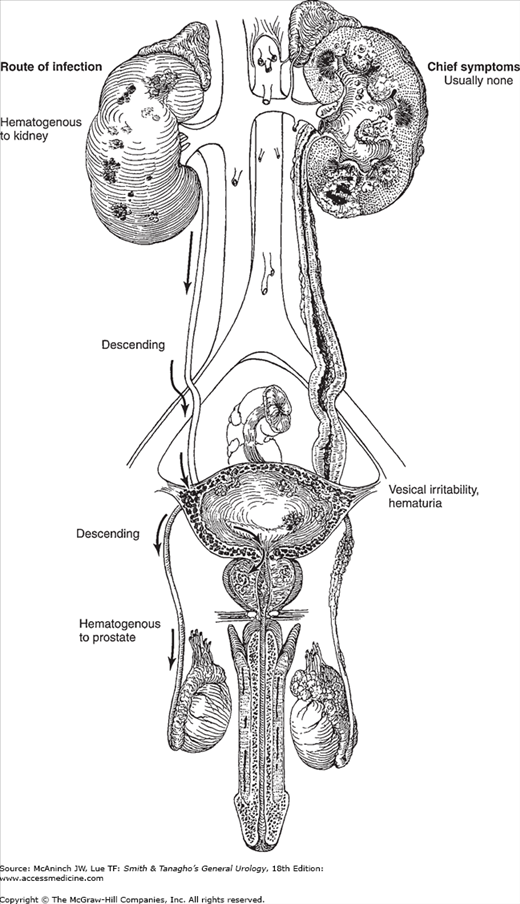

Tubercle bacilli may invade one or more (or even all) of the organs of the genitourinary tract and cause a chronic granulomatous infection that shows the same characteristics as tuberculosis in other organs. Urinary tuberculosis is a disease of young adults (60% of patients are between the ages of 20 and 40) and is more common in males than in females.

The infecting organism is Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which reaches the genitourinary organs by the hematogenous route from the lungs. The primary site is often not symptomatic or apparent.

The kidney and possibly the prostate are the primary sites of tuberculous infection in the genitourinary tract. All other genitourinary organs become involved by either ascent (prostate to bladder) or descent (kidney to bladder, prostate to epididymis). The testis may become involved by direct extension from epididymal infection.

When a shower of tubercle bacilli hits the renal cortex, the organisms may be destroyed by normal tissue resistance. Evidence of this is commonly seen in autopsies of persons who have died of tuberculosis; only scars are found in the kidneys. However, if enough bacteria of sufficient virulence become lodged in the kidney and are not overcome, a clinical infection is established.

Tuberculosis of the kidney progresses slowly; it may take 15–20 years to destroy a kidney in a patient who has good resistance to the infection. As a rule, therefore, there is no renal pain and little or no clinical disturbance of any type until the lesion has involved the calyces or the pelvis, at which time, pus and organisms may be discharged into the urine. It is only at this stage that symptoms (of cystitis) are manifested. The infection then proceeds to the pelvic mucosa and the ureter, particularly its upper and vesical ends. This may lead to stricture and obstruction (hydronephrosis).

As the disease progresses, a caseous breakdown of tissue occurs until the entire kidney is replaced by cheesy material. Calcium may be laid down in the reparative process. The ureter undergoes fibrosis and tends to be shortened and therefore straightened. This change leads to a “golf-hole” (gaping) ureteral orifice, typical of an incompetent valve.

Vesical irritability develops as an early clinical manifestation of the disease as the bladder is bathed by infected material. Tubercles form later, usually in the region of the involved ureteral orifice, and finally coalesce and ulcerate. These ulcers may bleed. With severe involvement, the bladder becomes fibrosed and contracted; this leads to marked frequency. Ureteral reflux or stenosis and, therefore, hydronephrosis may develop. If contralateral renal involvement occurs later, it is probably a separate hematogenous infection.

The passage of infected urine through the prostatic urethra ultimately leads to invasion of the prostate and one or both seminal vesicles. There is no local pain.

On occasion, the primary hematogenous lesion in the genitourinary tract is in the prostate. Prostatic infection can ascend to the bladder and descend to the epididymis.

Tuberculosis of the prostate can extend along the vas or through the perivasal lymphatics and affect the epididymis. Because this is a slow process, there is usually no pain. If the epididymal infection is extensive and an abscess forms, it may rupture through the scrotal skin, thus establishing a permanent sinus, or it may extend into the testicle.

The gross appearance of the kidney with moderately advanced tuberculosis is often normal on its outer surface, although the kidney is usually surrounded by marked perinephritis. Usually, however, there is a soft, yellowish localized bulge. On section, the involved area is seen to be filled with cheesy material (caseation). Widespread destruction of parenchyma is evident. In otherwise normal tissue, small abscesses may be seen. The walls of the pelvis, calyces, and ureter may be thickened, and ulceration appears frequently in the region of the calyces at the point at which the abscess drains. Ureteral stenosis may be complete, causing “autonephrectomy.” Such a kidney is fibrosed and functionless. Under these circumstances, the bladder urine may be normal and symptoms absent.

Tubercle foci appear close to the glomeruli. These are an aggregation of histiocytic cells possessing a vesicular nucleus and a clear cell body that can fuse with neighboring cells to form a small mass called an epithelioid reticulum. At the periphery of this reticulum are large cells with multiple nuclei (giant cells). This pathologic reaction, which can be seen macroscopically, is the basic lesion in tuberculosis. It can heal by fibrosis or coalesce and reach the surface and ulcerate, forming an ulcerocavernous lesion. Tubercles might undergo a central degeneration and caseate, creating a tuberculous abscess cavity that can reach the collecting system and break through. In the process, progressive parenchymal destruction occurs. Depending on the virulence of the organism and the resistance of the patient, tuberculosis is a combination of caseation and cavitation and healing by fibrosis and scarring.

Microscopically, the caseous material is seen as an amorphous mass. The surrounding parenchyma shows fibrosis with tissue destruction, small round cell and plasma cell infiltration, and epithelial and giant cells typical of tuberculosis. Acid–fast stains will usually demonstrate the organisms in the tissue. Similar changes can be demonstrated in the wall of the pelvis and ureter.

In both the kidney and ureter, calcification is common. It may be macroscopic or microscopic. Such a finding is strongly suggestive of tuberculosis but, of course, is also observed in bilharzial infection. Secondary renal stones occur in 10% of patients.

In the most advanced stage of renal tuberculosis, the parenchyma may be completely replaced by caseous substance or fibrous tissue. Perinephric abscess may develop, but this is rare.

In the early stages, the mucosa may be inflamed, but this is not a specific change. The bladder is quite resistant to actual invasion. Later, tubercles form and can be easily seen endoscopically as white or yellow raised nodules surrounded by a halo of hyperemia. With mural fibrosis and severe vesical contracture, reflux may occur.

Microscopically, the nodules are typical tubercles. These break down to form deep, ragged ulcers. At this stage, the bladder is quite irritable. With healing, fibrosis develops that involves the muscle wall.

Grossly, the exterior surface of these organs may show nodules and areas of induration from fibrosis. Areas of necrosis are common. In rare cases, healing may end in calcification. Large calcifications in the prostate should suggest tuberculous involvement.

The vas deferens is often grossly involved; fusiform swellings represent tubercles that in chronic cases are characteristically described as beaded. The epididymis is enlarged and quite firm. It is usually separate from the testis, although occasionally it may adhere to it. Microscopically, the changes typical of tuberculosis are seen. Tubular degeneration may be marked. The testis is usually not involved except by direct extension of an abscess in the epididymis.

Infections are usually carried by the bloodstream; rarely, they are the result of sexual contact with an infected male. The incidence of associated urinary and genital infection in women ranges from 1% to 10%. The uterine tubes may be affected. Other presentations include endarteritis, localized adnexal masses (usually bilateral), and tuberculous cervicitis, but granulomatous lesions of the vaginal canal and vulva are rare.

Tuberculosis of the genitourinary tract should be considered in the presence of any of the following situations: (1) chronic cystitis that refuses to respond to adequate therapy; (2) the finding of sterile pyuria; (3) gross or microscopic hematuria; (4) a nontender, enlarged epididymis with a beaded or thickened vas; (5) a chronic draining scrotal sinus; or (6) induration or nodulation of the prostate and thickening of one or both seminal vesicles (especially in a young man). A history of present or past tuberculosis elsewhere in the body should cause the physician to suspect tuberculosis in the genitourinary tract when signs or symptoms are present.

The diagnosis rests on the demonstration of tubercle bacilli in the urine by culture or positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The extent of the infection is determined by (1) the palpable findings in the epididymides, vasa deferentia, prostate, and seminal vesicles; (2) the renal and ureteral lesions as revealed by imaging; (3) involvement of the bladder as seen through the cystoscope; (4) the degree of renal damage as measured by loss of function; and (5) the presence of tubercle bacilli in one or both kidneys.

There is no classic clinical picture of renal tuberculosis. Most symptoms of this disease, even in the most advanced stage, are vesical in origin (cystitis). Vague generalized malaise, fatigability, low-grade but persistent fever, and night sweats are some of the nonspecific complaints. Even vesical irritability may be absent, in which case only proper collection and examination of the urine will afford the clue. Active tuberculosis elsewhere in the body is found in less than half of patients with genitourinary tuberculosis.

Because of the slow progression of the disease, the affected kidney is usually completely asymptomatic. On occasion, however, there may be a dull ache in the flank. The passage of a blood clot, secondary calculi, or a mass of debris may cause renal and ureteral colic. Rarely, the presenting symptom may be a painless mass in the abdomen.

The earliest symptoms of renal tuberculosis may arise from secondary vesical involvement. These include burning, frequency, and nocturia. Hematuria is occasionally found and is of either renal or vesical origin. At times, particularly in a late stage of the disease, the vesical irritability may become extreme. If ulceration occurs, suprapubic pain may be noted when the bladder becomes full.

Tuberculosis of the prostate and seminal vesicles usually causes no symptoms. The first clue to the presence of tuberculous infection of these organs is the onset of a tuberculous epididymitis.

Tuberculosis of the epididymis usually presents as a painless or only mildly painful swelling. An abscess may drain spontaneously through the scrotal wall. A chronic draining sinus should be regarded as tuberculous until proved otherwise. In rare cases, the onset is quite acute and may simulate an acute nonspecific epididymitis.

Evidence of extragenital tuberculosis may be found (lungs, bone, lymph nodes, tonsils, intestines).

There is usually no enlargement or tenderness of the involved kidney.

A thickened, nontender, or only slightly tender epididymis may be discovered. The vas deferens often is thickened and beaded. A chronic draining sinus through the scrotal skin is almost pathognomonic of tuberculous epididymitis. In the more advanced stages, the epididymis cannot be differentiated from the testis on palpation. This may mean that the testis has been directly invaded by the epididymal abscess.

Hydrocele occasionally accompanies tuberculous epididymitis. The idiopathic hydrocele should be tapped so that underlying pathologic changes, if present, can be evaluated (epididymitis, testicular tumor). Involvement of the penis and urethra is rare.

These organs may be normal to palpation. Ordinarily, however, the tuberculous prostate shows areas of induration, even nodulation. The involved seminal vesicle is usually indurated, enlarged, and fixed. If epididymitis is present, the ipsilateral seminal vesicle usually shows changes as well.

Proper urinalysis affords the most important clue to the diagnosis of genitourinary tuberculosis.

Persistent pyuria without organisms on culture means tuberculosis until proved otherwise. Acid–fast stains done on the concentrated sediment from a 24-hour specimen are positive in at least 60% of cases. However, this must be corroborated by a positive culture.

If clinical response to adequate treatment of bacterial infection fails and pyuria persists, tuberculosis must be ruled out by bacteriologic and imaging.

Cultures for tubercle bacilli from the first morning urine are positive in a very high percentage of cases of tuberculous infection. If positive, sensitivity tests should be ordered. In the face of strong presumptive evidence of tuberculosis, negative cultures should be repeated. Three to five first morning voided specimens are ideal.

It can also be infected with tubercle bacilli, or it may become hydronephrotic from fibrosis of the bladder wall (ureterovesical stenosis) or vesicoureteral reflux.

If tuberculosis is suspected, the tuberculin test should be performed. A positive test, particularly in an adult, is hardly diagnostic, but a negative test in an otherwise healthy patient speaks against a diagnosis of tuberculosis.

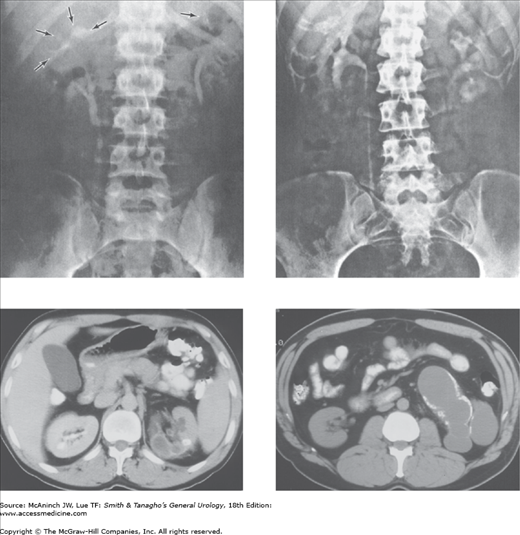

A plain film of the abdomen may show enlargement of one kidney or obliteration of the renal and psoas shadows due to perinephric abscess. Punctate calcification in the renal parenchyma may be due to tuberculosis. Renal stones are found in 10% of cases. Calcification of the ureter may be noted, but this is rare (Figure 15–2).

Figure 15–2.

Radiologic evidence of tuberculosis. Upper left: Excretory urogram showing “moth-eaten” calyces in upper renal poles. Calcifications in upper calyces; right upper ureter is straight and dilated. Upper right: Excretory urogram showing ulcerated and dilated calyces on the left. Lower left: Abdominal computed tomography (CT) with contrast showing left renal tuberculosis with calcification, poor parenchymal perfusion, and surrounding inflammation. Lower right: Noncontrast abdominal CT showing late effects of renal TB with calyceal dilation, loss of parenchyma, and urothelial calcifications. (CT images courtesy of Fergus Coakley, MD, UCSF Radiology.)

Excretory urograms can be diagnostic if the lesion is moderately advanced. The typical changes include (1) a “moth-eaten” appearance of the involved ulcerated calyces; (2) obliteration of one or more calyces; (3) dilatation of the calyces due to ureteral stenosis from fibrosis; (4) abscess cavities that connect with calyces; (5) single or multiple ureteral strictures, with secondary dilatation, with shortening and therefore straightening of the ureter; and (6) the absence of function of the kidney due to complete ureteral occlusion and renal destruction (autonephrectomy). Ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) also show the calcifications, renal contractions and scars, and ureteral and calyceal strictures suggestive of genitourinary tuberculosis. Ultrasound has the advantage of low cost and low invasiveness. Contrast CT scan is highly sensitive for calcifications and the characteristic anatomic changes.

Thorough cystoscopic study is indicated even when the offending organism has been found in the urine and excretory urograms show the typical renal lesion. This study clearly demonstrates the extent of the disease. Cystoscopy may reveal the typical tubercles or ulcers of tuberculosis. Biopsy can be done if necessary. Severe contracture of the bladder may be noted. A cystogram may reveal ureteral reflux.

Chronic nonspecific cystitis or pyelonephritis may mimic tuberculosis perfectly, especially since 15–20% of cases of tuberculosis are secondarily invaded by pyogenic organisms. If nonspecific infections do not respond to adequate therapy, a search for tubercle bacilli should be made. Painless epididymitis points to tuberculosis. Cystoscopic demonstration of tubercles and ulceration of the bladder wall means tuberculosis. Urograms are usually definitive.

Acute or chronic nonspecific epididymitis may be confused with tuberculosis, since the onset of tuberculosis is occasionally quite painful. It is rare to have palpatory changes in the seminal vesicles with nonspecific epididymitis, but these are almost routine findings in tuberculosis of the epididymis. The presence of tubercle bacilli on a culture of the urine is diagnostic. On occasion, only the pathologist can make the diagnosis by microscopic study of the surgically removed epididymis.

Multiple small renal stones or nephrocalcinosis seen by x-ray may suggest the type of calcification seen in the tuberculous kidney. In renal tuberculosis, the calcium is in the parenchyma, although secondary stones are occasionally seen.

Necrotizing papillitis, which may involve all of the calyces of one or both kidneys or, rarely, a solitary calyx, shows caliceal lesions (including calcifications) that simulate those of tuberculosis. Careful bacteriologic studies fail to demonstrate tubercle bacilli.

Medullary sponge kidneys may show small calcifications just distal to the calyces. The calyces are sharp, however, and no other stigmas of tuberculosis can be demonstrated.

In disseminated coccidioidomycosis, renal involvement may occur. The renal lesion resembles that of tuberculosis. Coccidioidal epididymitis may be confused with tuberculous involvement.

Urinary bilharziasis is a great mimic of tuberculosis. Both present with symptoms of cystitis and often hematuria. Vesical contraction, seen in both diseases, may lead to extreme frequency. Schistosomiasis must be suspected in endemic areas; the typical ova are found in the urine. Cystoscopic and urographic findings are definitive for making the diagnosis.

Perinephric abscess may cause an enlarging mass in the flank. A plain film of the abdomen shows obliteration of the renal and psoas shadows. Sonograms and CT scans may be more helpful. Renal stones may develop if secondary nonspecific infection is present. Uremia is the end stage if both kidneys are involved.

Scarring with stricture formation is one of the typical lesions of tuberculosis and most commonly affects the juxtavesical portion of the ureter. This may cause progressive hydronephrosis. Complete ureteral obstruction may cause complete nonfunction of the kidney (autonephrectomy).

When severely damaged, the bladder wall becomes fibrosed and contracted. Stenosis of the ureters or reflux occurs, causing hydronephrotic atrophy.

The ducts of the involved epididymis become occluded. If this is bilateral, sterility results. Abscesses of the epididymis may invade the testes and even involve the scrotal skin.

Genitourinary tuberculosis is extrapulmonary tuberculosis. The primary treatment is medical therapy. Surgical excision of an infected organ, when indicated, is merely an adjunct to overall therapy.

A strict medical regimen should be instituted. A combination of drugs is usually desirable. The following drugs are effective in combination: (1) isoniazid (INH), 200–300 mg orally once daily; (2) rifampin (RMP), 600 mg orally once daily; (3) ethambutol (EMB), 25 mg/kg daily for 2 months, then 15 mg/kg orally once daily; (4) streptomycin, 1 g intramuscularly once daily; and (5) pyrazinamide, 1.5–2 g orally once daily. It is preferable to begin treatment with a combination of isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol. The European Association of Urology guidelines recommends 2 or 3 months of intensive triple drug therapy (INH, RMP, and EMB) daily followed by 3 months of continuation therapy with INH and RMP two or three times per week. If resistance to one of these drugs develops, one of the others listed should be chosen as a replacement. The following drugs are usually considered only in cases of resistance to first-line drugs and when expert medical personnel are available to treat toxic side effects, should they occur: aminosalicylic acid (PAS), capreomycin, cycloserine, ethionamide, pyrazinamide, viomycin. Pyrazinamide may cause serious liver damage.

Tuberculosis of the bladder is always secondary to renal or prostatic tuberculosis; it tends to heal promptly when definitive treatment for the “primary” genitourinary infection is given. Vesical ulcers that fail to respond to this regimen may require transurethral electrocoagulation. Vesical instillations of 0.2% monoxychlorosene (Clorpactin) may also stimulate healing.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree