Chapter 69B Simple cysts and polycystic liver disease

Surgical and nonsurgical management

Single Cysts

Asymptomatic liver cysts, even when large, need no treatment and do not require surveillance. A small percentage of patients have symptoms related to an increase in the size of cysts (see Chapter 69A). Caution must be exercised when considering whether a simple cyst is symptomatic when it is smaller than 8 cm or when it does not protrude outside of the liver surface. If this is not the case, or if symptoms are vague, ultrasound-guided aspiration of the cyst may be attempted as a therapeutic test. If this does not result in improvement of symptoms, further treatment is not required. When aspiration is effective at relieving symptoms, the cyst is symptomatic. Improvement, however, is transient, as the cyst inevitably recurs after simple aspiration (Saini et al, 1983), and more radical treatment, such as sclerotherapy or fenestration, can be considered.

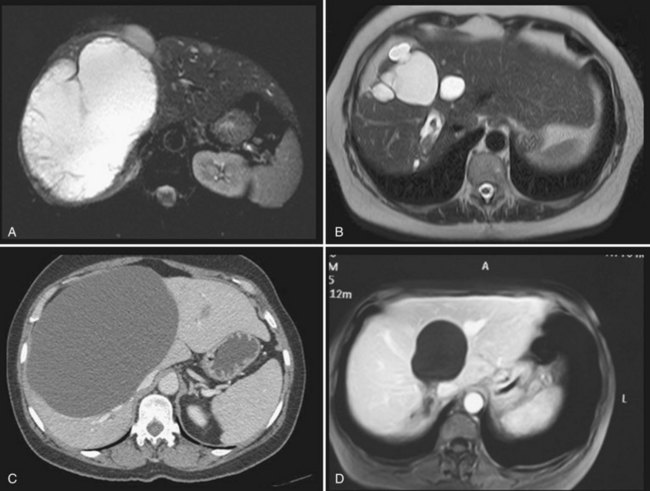

It is unclear whether treatment is indicated in patients who are asymptomatic but nevertheless have evidence on imaging of compression of the bile ducts, or of portal or hepatic veins, by the cysts. If these anomalies are unilateral—that is, at least one hemiliver has normal biliary drainage and normal inflow and outflow—our opinion is that treatment is not required, as the stenosis is not always reversible (Fig. 69B.1).

Sclerotherapy

Method

Sclerotherapy aims at destroying the epithelium lining the inner surface of the wall to stop intracystic fluid secretion (see Chapter 28). Under US guidance, the cyst is located and punctured, and a small drainage catheter is introduced by the Seldinger technique. Injection of water-soluble contrast media ensures that no communication with the bile duct exists and that no leak into the peritoneal cavity is present, both of which are contraindications (Tikkakoski et al, 1996).

The most frequently used sclerosing agent is 95% ethanol, as for renal cysts. Minocycline hydrochloride, otherwise used for pleurodesis or, more recently, ethanolamine oleate (Miyamoto et al, 2006; Nakaoka et al, 2009) have been proposed as alternatives. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has also been performed, although reports are only anecdotal.

The amount of ethanol injected should be limited because alcohol sclerotherapy is associated with an increase in blood alcohol concentration, peaking 3 to 4 hours after treatment (Yang et al, 2006). As massive ethanol intoxication leading to coma has been reported after injection of 240 mL in a 3500 mL cyst (Wernet et al, 2008), the volume of alcohol should not exceed 100 to 120 mL. To ensure that the sclerosant comes in contact with the entire surface, the patient is rolled in different positions. Alcohol is then aspirated and the catheter removed. The procedure is performed with the patient under light general anesthesia because it is painful.

Several protocols have been designed that differ in the duration of alcohol retention in the cyst (from 10 to 240 minutes) and in the number of sessions (single or multiple) (Larssen et al, 2003; Simonetti et al, 1993; Tikkakoski et al, 1996; Yang et al, 2006). Comparative studies are lacking, but a single study showed that 120- and 240-minute retention times yield comparable results (Yang et al, 2006).

Recently, prolonged catheter drainage with negative pressure of the cyst without sclerotherapy has been shown to be as effective as alcohol injection in a randomized study (Zerem, 2009). This result mainly shows that an important aspect of percutaneous treatments in general is to achieve collapse of the cystic cavity.

Complications

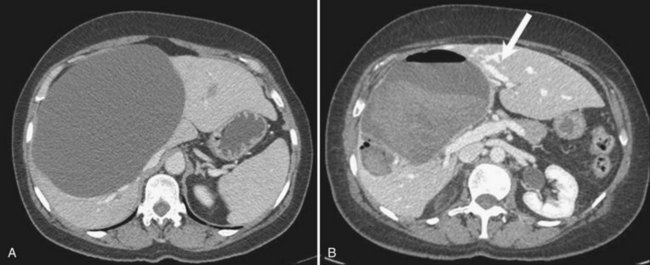

Although the injection is painful, pain resolves rapidly and most patients are discharged the following day. Transient neuropsychic disorders secondary to diffusion of alcohol through the cyst wall have been reported. Intracystic bleeding is rare but potentially severe (Fig. 69B.2). It should be realized that vessels are compressed at the periphery of enlarged cysts because of the high intracystic pressure and are therefore not visible; however, bleeding may occur once the cysts have emptied if a vessel has been inadvertently punctured.

Long-Term Outcome

A systematic literature review published in 2001 identified 112 patients treated by alcohol sclerotherapy and 17 treated with minocycline hydrochloride instillation (Moorthy et al, 2001). In most patients, a complete or partial regression of the cyst was seen, but follow-up was short overall. Although the reported experience since then has been limited, the efficacy has been confirmed, with a symptomatic recurrence rate requiring additional treatment of less than 5% (Erdogan et al, 2007).

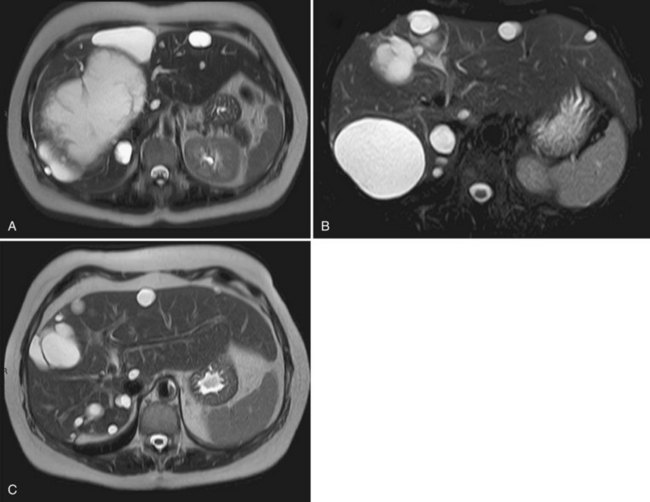

An early morphologic assessment, usually by US, is frequently performed. However, patients should be warned that this is likely to show the persistence of the cyst, although at a smaller size; this is not predictive of symptomatic recurrence. In practice, several months—perhaps up to a year—may be required to achieve optimal efficacy after alcohol sclerotherapy (Fig. 69B.3).

Fenestration

Limitations

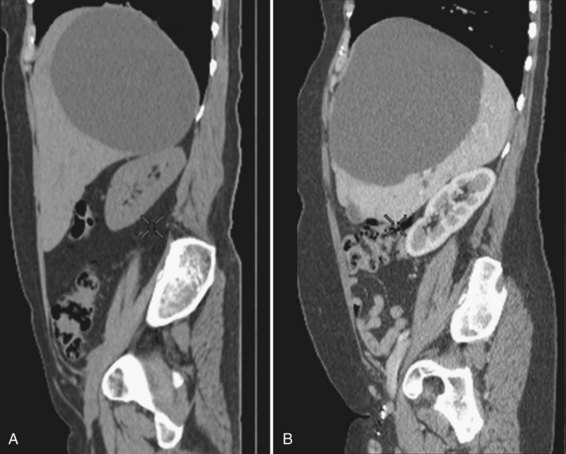

Cysts protruding into segments VII or VIII are not formal contraindications to laparoscopic fenestration, but the procedure is unlikely to be very successful in such a case because limited access will prevent wide unroofing. In addition, the margins of the opening may adhere to the diaphragm, and the risk of cyst recurrence is increased as a result of contained secretion (Fig. 69B.4). Open fenestration is a wise alternative in this circumstance.

Complications

The most severe intraoperative complication is bleeding, and transfusion has occasionally been required (Loehe et al, 2010). This occurs when the liver parenchyma, not the cyst wall, is opened. Conversion, the most frequent indication for which is bleeding, is required in less than 5% of patients.

Postoperative complications are rare, and patients are usually discharged after 1 to 3 days. No deaths have been reported, and morbidity ranges between 0% and 15% (Gall et al, 2009; Loehe et al, 2010). The most severe complications include biliary leak and hemorrhage, which result from reexpansion of biliary and vascular structures that were compressed at the interface between the cyst wall and the parenchyma and that were inadequately secured. If the periphery of the opened cyst is thick, it should be closed with running sutures; an alternative is to use an endovascular stapler on these portions of the cyst wall because it allows wide fenestration while maintaining hemostasis. Ascites is very rare after fenestration of simple cysts, unlike PCLD (see below).

Long-Term Outcome

Long-term efficacy of fenestration for simple cysts is still somewhat unclear. Reported experience is limited, follow-up is usually short, and results are not always stratified according to the number of cysts (i.e., simple cysts vs. PCLD). Furthermore, cyst recurrence, symptomatic recurrence, and the need for additional treatment are not always distinguished. It is usually assumed that although cysts may recur in one third to one half of patients, symptomatic recurrence occurs in less than 5% (Hansman et al, 2001; Morino et al, 1994; Tan et al, 2005); however, higher figures of symptomatic recurrence (15% to 20%) have been reported (Erdogan et al, 2007; Gall et al, 2009; Martin et al, 1998).

A more precise comparison of preoperative and postoperative symptoms has recently been published (Loehe et al, 2010). Abdominal pain was improved in 91% of patients and disappeared in 68%. Other symptoms—including impaired gastrointestinal transport, early satiety, nausea, vomiting, and acid reflux—disappeared in 53% of the patients. Overall, within 1 year of surgery, 32% of the patients developed or had persistent subjective symptoms in this series, but this rate decreased to 7% and 2% after 3 and 5 years, respectively. During follow-up, 9% required reoperation.

Persistent symptoms may be related to technical failure or reflect inaccurate selection, with some patients undergoing surgery for non–cyst-related symptoms (see Chapter 69A).

Sclerotherapy Versus Fenestration

Although both techniques have been used for years, no randomized or prospective comparative analysis has been done. As a rule, the severity of symptoms that leads to treatment has not been standardized, and recurrence is poorly defined. It would seem that both methods are almost as effective (Erdogan et al, 2007; Furuta et al, 1990; Moorthy et al, 2001). Our policy is to systematically attempt sclerotherapy first; fenestration is indicated in cases of recurrence, but location of the protruding part of the cyst may influence this choice (see Fig. 69B.4).

Polycystic Liver Disease

Symptoms in PCLD are related mainly to the volume of the entire liver rather than to the volume of a specific cyst. Although palliation with percutaneous alcohol sclerotherapy or laparoscopic fenestration has been reported, neither proves effective in the long term in the most frequent forms of PCLD (Robinson et al, 2005). The aim of treatment is instead to decompress and reduce the size of the entire liver or to remove as many cysts as possible. In highly symptomatic patients, these objectives can be achieved by open fenestration, liver resection, or liver transplantation. Patients should be carefully informed of the limitations and risks of these procedures. Medical alternatives have been recently introduced, although larger studies are required to confirm their clinical impact.

Nonsurgical Treatments

Medical Treatment

Avoidance of Estrogen Replacement Therapy

Avoidance of estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) would seem logical as medical treatment for PCLD because hepatic cystic disease may worsen under the influence of hormones of pregnancy or exogenous female steroid hormones (Shrestha et al, 1997). However, proof that avoidance is effective is lacking, and the benefits and drawbacks should be discussed on an individual basis.

Somatostatin Analogues

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) is a potent mediator of cholangiocyte proliferation and secretion of fluid into cysts (see Chapter 69A). Somatostatin receptors are expressed on cholangiocytes; when triggered, this activates a signaling cascade that suppresses cAMP. Somatostatin blunts hepatic cyst expansion by blocking secretin-induced cAMP generation (Masyuk et al, 2007). It also suppresses the expression of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and other cystogenic growth factors and downstream signaling from their receptors (Pyronnet et al, 2008). Two randomized controlled trials have recently demonstrated that 6 or 12 months of treatment with lanreotide, a long-acting somatostatin analogue, was associated with a significant reduction of liver volume in patients with PCLD, with or without autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), compared with placebo-treated controls (Hogan et al, 2010; van Keimpema et al, 2009

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree