Short bowel syndrome

Javier Bueno MD

Introduction

Short bowel syndrome (SBS) is a transitory or permanent intestinal failure due to the anatomic loss of extensive segments of small intestine clinically manifested with diarrhoea, malabsorption, and malnutrition. SBS is the most frequent cause of intestinal failure in the paediatric population and occurs perinatally in 85%1, 2. Although it can be congenital, it occurs most frequently after small bowel resection due to gut disorders (13.1) (Table 13.1).

The intestinal length in the term newborn is 2.5-3 m and between 6 and 8 m in the adult3. The definitive intestinal length to develop SBS is not well established. In adults it is considered if the intestinal length is <200 cm. In children it depends on age, but it is considered if the length is <80-100 cm, and it will be severe if <40 cm1, 2, 4. The patho-physiological consequences of a bowel resection depend on the extent and site of the intestinal resection, and the adaptability of the remaining intestine.

Adaptation process

After a massive small bowel resection, the remnant intestine suffers an adaptation process that includes an increase in villous height and mucosal surface area, as well as in bowel luminal circumference and wall thickness5.

Enteral nutrition is the principal adaptation stimuli by its trophic effect, avoiding mucosa atrophy2. It promotes the enterohepatic recirculation of biliary salts and the release of hormones and pancreato-biliary secretions that maintain the integrity and intestinal function. The length and site of resection are obviously important: ileal resection is worse tolerated than jejunal2, 6. The presence of the ileocaecal valve improves the prognosis. It increases transit time and the contact of nutrients with the mucosa. In addition, it avoids bacterial overgrowth. In children, if intestinal length is <40 cm without ileocaecal valve there is 40% of probability of permanent parenteral nutrition (PN) dependence. If the intestinal length is between 40 and 80 cm

and the valve is present, 80% can achieve nutritional autonomy in 1 year5.

and the valve is present, 80% can achieve nutritional autonomy in 1 year5.

Table 13.1 Main causes of short gut in children | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

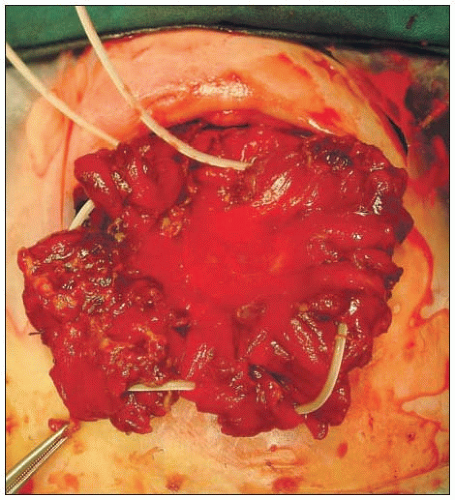

Preservation of colon is not only important for the absorption of fluid and electrolytes, but it also has nutritional advantages: malabsorbed carbohydrates undergo bacterial fermentation in the residual colon where they are converted into short-chain fatty acids7. The presence of a jejunostomy or a terminal ileostomy can produce high output with dehydration and electrolytes disturbances, delaying the adaptative process (13.2)4.

Bacterial overgrowth is frequent due to the absence of the ileocaecal valve, presence of intestinal strictures, and intestinal dysmotility. It can produce enteritis that worsens the adaptation process8. It is also involved in the pathogenesis of the PN-related liver failure. Established liver damage also interfere with adaptation1.

Initial supportive management

Treatment of children with intestinal failure should be predicated upon three goals: (1) to keep the patient well nourished by PN, (2) to minimize the faecal losses of fluid, electrolytes, and nutrients, and (3) to enhance the natural process of intestinal adaptation whenever possible.

Parenteral nutrition

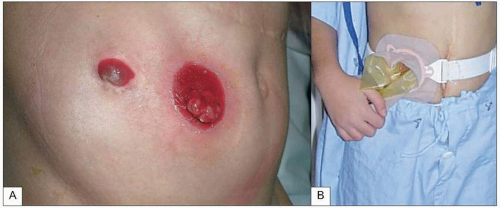

Most patients require PN until their gut has undergone sufficient adaptation to allow survival on an oral diet. This period is variable and can take 18-45 months6. PN is the practice of feeding a person intravenously (13.3). It is usually administered through a permanent central line (13.4)4. Surgical venotomies should be avoided in order to preserve the veins.

13.2 End jejunostomy. The presence of a jejunostomy or a terminal ileostomy can produce high output with dehydration and electrolytes disturbances, delaying the adaptation process. |

Long-term PN may be associated with complications that include recurrent central venous line sepsis and liver failure (Table 13.2). In children, hepatic dysfunction is a major problem(13.5)1, 2, 4. Patients with permanent intestinal failure sooner or later will develop cirrhosis and liver failure1. Sondheimer et al. reported that 67% of neonates with PN-dependent SBS developed cholestasis, and 17% progressed to liver failure9. Strategies to avoid or delay liver failure are shown in Table 13.3. Patients with SBS frequently develop other clinical problems which may require specific therapy (Table 13.4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree