Cholestasis should be diagnosed quickly in infancy as various diseases require immediate therapy. Numerous aetiologies make diagnosis difficult. The American Academy of Pediatrics has elaborated practical guidelines for the management of hyperbilirubinaemia in newborn infants, mainly concentrating on indirect hyperbilirubinemia

1. The guidelines emphasise the importance of measuring direct bilirubin in sick infants and in those who are jaundiced at or beyond 3 weeks. If the direct or conjugated bilirubin level is elevated, additional assessment for the causes of cholestasis is recommended. For instance, hypothyroidism, galactosaemia, and tyrosinaemia should be taken into account. Infectious diseases may also cause cholestasis, thus urinary tract infections as well as cytomegalovirus (

CMV) and toxoplasmosis should be excluded. The role of

CMV as the causative factor of cholestasis is still under debate, as congenital

CMV infections may present with liver damage and cholestasis. It is very important to assess stool colour to make a timely diagnosis of biliary atresia (

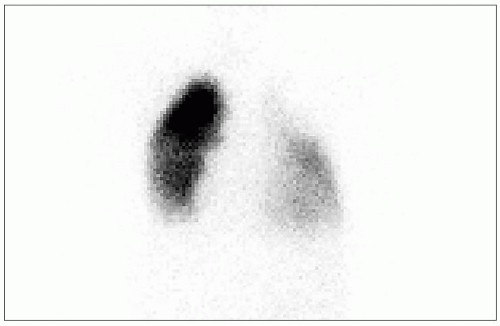

BA).

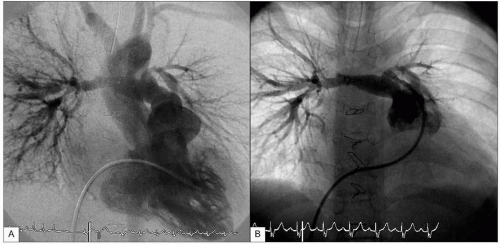

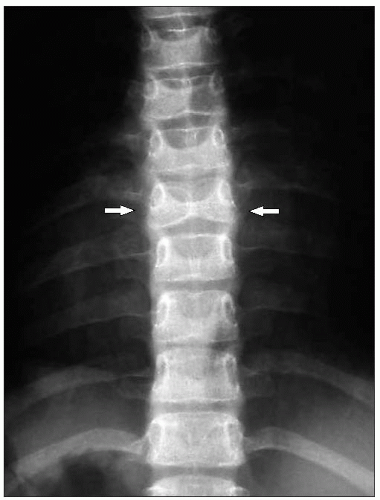

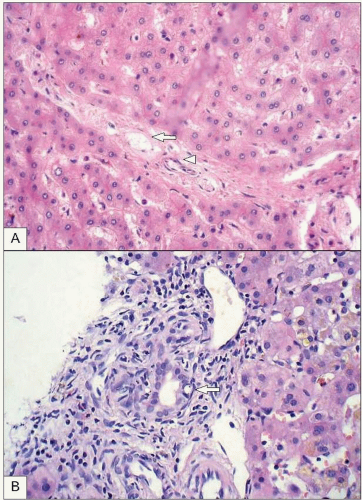

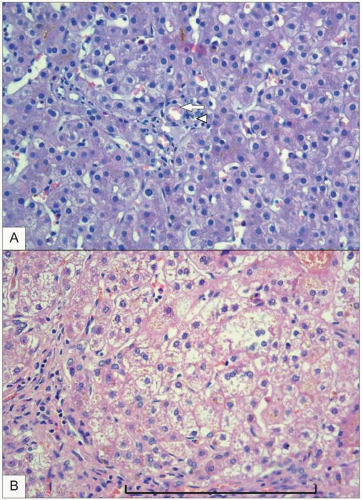

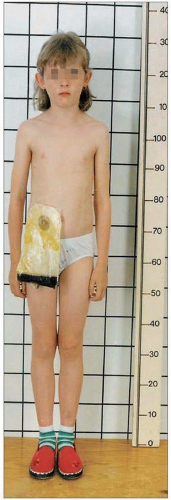

BA is a relatively uncommon disease characterized by a biliary obstruction of unknown origin that presents in the neonatal period

2. However, it is the most important surgically correctable cause of cholestatic jaundice in this age group and is the most common indication for liver transplantation in children. Untreated,

BA leads to cirrhosis and death within the first years of life. Surgical treatment usually involves an initial attempt to restore bile flow: the Kasai portoenterostomy

3 which is performed as soon after diagnosis as possible. Prognosis of the disease seems to be better in infants operated on before 90 days of age

4. Other causes of cholestasis with pale stools are: Alagille syndrome, progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (

PFIC), alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency (

α1-ATD), and cystic fibrosis. Neonatal haemochromatosis, Zellweger syndrome, Niemann-Pick disease type C, and glycogen storage disease type IV should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of infantile cholestasis (

Tables 9.1,

9.2).

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access