Fig. 12.1

Representative image of basal plasmacytosis in severely active chronic colitis. This image demonstrates colonic mucosa with marked crypt distortion, crypt abscesses, expansion of lamina propria by a chronic lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with prominent basal plasmacytosis (outlined by brackets). (Hematoxylin and eosin, ×100)

The clinical importance of MH in UC is independent of treatment type and is true across all drug classes. Meucci and colleagues showed that UC patients who attained clinical and endoscopic remission treated with oral and topical mesalamine for 6 weeks had a 23 % 1-year relapse rate in contrast to an 80 % relapse rate for patients who only went into clinical remission (P < 0.0001) [12]. Ardizzone et al. found that patients who achieved endoscopic remission at 3 months after their first course of corticosteroids were less likely to be hospitalized (25 vs. 49 %, P = 0.015) or require a colectomy (3 vs. 18 %, P = 0.027 ) over a 5-year follow-up period compared to patients who were in clinical remission but had persistent mucosal disease [13]. Similar results were observed in the ACT1 and ACT2 UC infliximab trials, in which MH at 8 weeks of infliximab treatment significantly decreased the 1-year risk of colectomy compared with treated patients without MH (p <0.001) and correlated with increased rates of clinical and corticosteroid free remission at 30 and 54 weeks (p <0.0001) [14].

Significance of Mucosal Healing in Crohn’s Disease

MH appears to be important for CD, but its significance and application in CD is less clear-cut than in UC. CD involves transmural injury and locations in the intestine that may not be accessible to endoscopy [3]. As in UC, multiple studies, particularly from the Groupe d’Etudes Therapeutiques des Affections Inflammatoires Digestive (GETAID), have found that clinical symptoms and mucosal disease activity do not often correlate in CD. For example Modigliani and colleagues found that only 29 % of colonic and ileocolonic Crohn’s disease patients who achieved corticosteroid-induced clinical remission also attained endoscopic remission [15]. Accordingly, the objective nature of MH may prove to be a worthwhile treatment goal rather than subjective clinical remission to decrease the risk of progressive and irreversible tissue destruction seen in CD, such as intestinal strictures and penetrating complications. Ultimately a measure of structural damage that accounts for the transmural process of CD would be a valuable tool for assessing disease progression or improvement to treatment. Lemann and colleagues have initiated such a CD scoring system that accounts for disease involvement beyond endoscopic mucosal assessment [16].

The IBSEN cohort study demonstrated that Crohn’s patients who developed MH at 1 year after diagnosis were less likely to require intestinal resection by 5 years compared to patients without MH (11 % vs. 20 %) [6], and this difference became significant by 10 years and translated into a 60 % risk reduction [17]. Similarly, Baert and colleagues found that complete MH at 2 years after CD diagnosis and treatment initiation was the only predictive factor that correlated with a sustained corticosteroid-free clinical remission, as 71 % of patients with MH were in remission at 3 and 4 years of follow-up compared to only 27 % of patients who had persistent disease activity at 2 years (P = 0.036) [18].

As in UC, the clinical significance of mucosal healing appears to be independent of treatment choice. In a study detailing the superiority of azathioprine versus budesonide at inducing and maintaining complete or partial MH after 1 year of treatment (83 % vs. 24 %, p = 0.0001), azathioprine-treated patients also had a higher rate of clinical remission over an 18 month follow-up period (76 vs. 36 %, respectively, P = 0.03) [19]. Regarding tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, Schnitzler and colleagues prospectively investigated a cohort of CD patients treated with infliximab and found those patients who achieved complete or partial MH required fewer hospitalizations (42 vs. 59 %, P = 0.0018) and less major abdominal surgery (14 vs. 38 %, P < 0.0001) than CD patients with no MH [20]. Likewise, in a subgroup analysis of the randomized maintenance infliximab ACCENT 1 trial (A Crohn’s Disease Clinical Trial Evaluating Infliximab in a New Long-term Treatment Program), 18 % of CD patients in endoscopic remission at either 10 and/or 54 weeks of treatment had CD-related hospital admissions compared to 28 % of patients with no healing at either time point, and none of the 9 patients who had MH at both time points required hospitalization at 1 year follow-up [21].

The importance of MH or endoscopic remission in CD has been further appreciated in the postoperative setting. Rutgeerts and colleagues found in their initial seminal study of the natural history of postoperative recurrent CD that 72 % of examined patients (21 out of 29) had recurrent endoscopic CD within 1 of year of curative resection and that a remarkable number of these patients were asymptomatic [22]. In a subsequent prospective cohort 8 year follow-up study of 89 patients after resection, Rutgeerts and his team found that only 20 % and 34 % of patients were symptomatic 1 and 3 years after surgery, respectively, despite endoscopic disease found in 73 % and 85 % of these patients [23]. Regueiro and colleagues observed similar findings in their postoperative randomized placebo-controlled infliximab trial, as they determined the kappa coefficient of agreement between the patients’ endoscopic scores and their clinical Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) scores was only 0.12 [24].

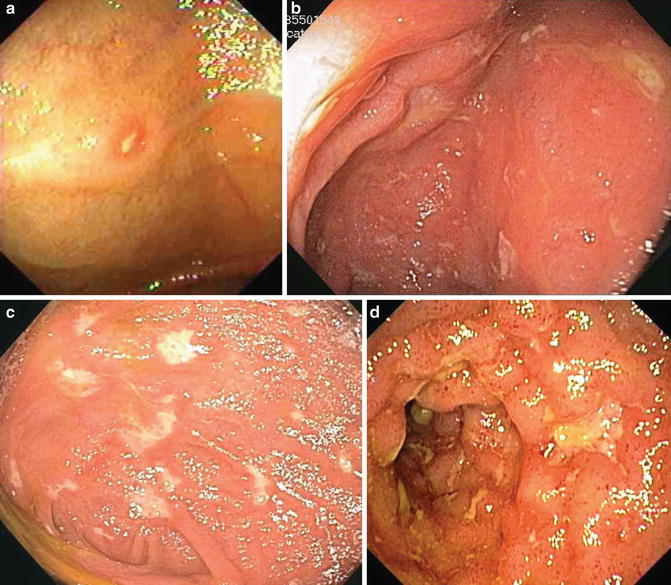

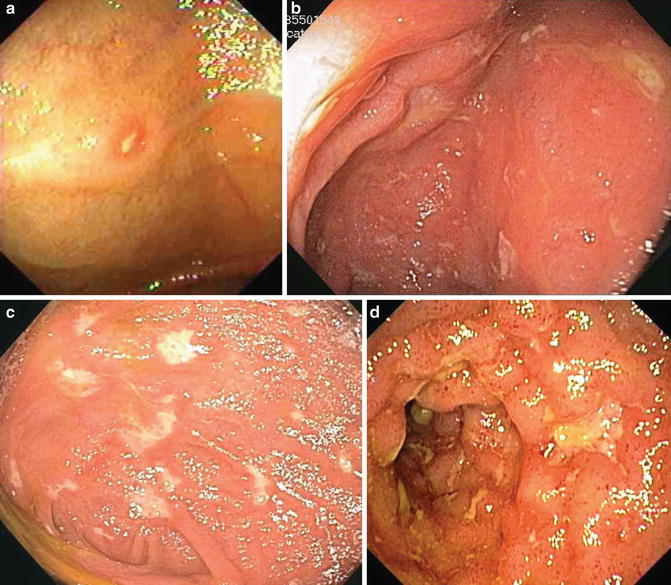

Rutgeerts and colleagues went on to show that the degree of endoscopic disease severity at 1 year, as judged by the now classified Rutgeerts score (Table 12.1, Fig. 12.2a–d), directly correlated with the progression to symptomatic recurrence and that the endoscopic score was the most statistically significant variable in predicting outcome [23]. For example, only 8.6 % of patients with no or only mild endoscopic disease at 1 year, as defined by Rutgeerts score i0 or i1, had clinical symptoms at 8 years, while 100 % of patients with severe endoscopic disease, as defined by Rutgeerts score i4, had symptomatic recurrence by 4 years.

Table 12.1

Rutgeerts postoperative Crohn’s disease endoscopic scoring system

Endoscopic score | Endoscopic findings |

|---|---|

i0 | No lesions |

i1 | ≤5 aphthous lesions |

i2 | >5 aphthous lesions with normal mucosa between the lesions, or skip areas of larger lesions or lesions confined to the ileocolonic anastomosis (i.e.:<1 cm in length) |

i3 | Diffuse aphthous ileitis with diffusely inflamed mucosa |

i4 | Diffuse inflammation with already larger ulcers, nodules, and/or narrowing |

Fig. 12.2

Representative images of the Rutgeerts postoperative Crohn’s disease endoscopic scoring system: (a) i1 with <5 aphthous lesions, (b) i2 with >5 aphthous lesions, (c) i3 with diffuse aphthous ileitis, and (d) i4 with diffuse inflammation and narrowing

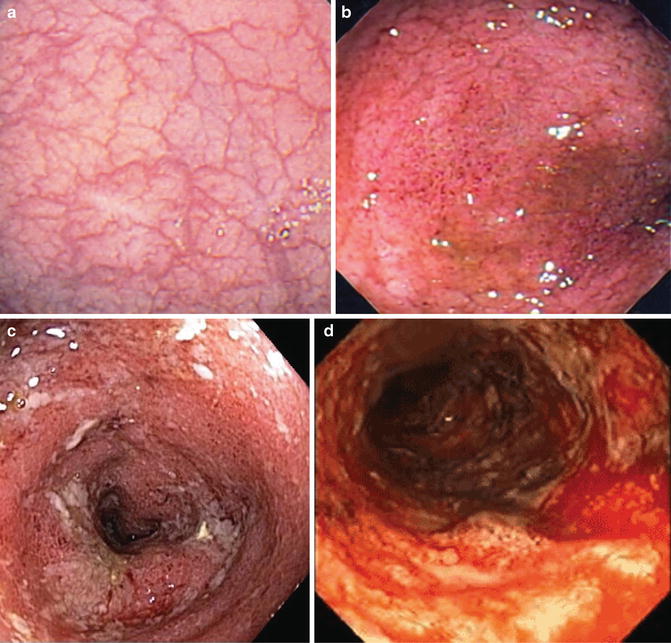

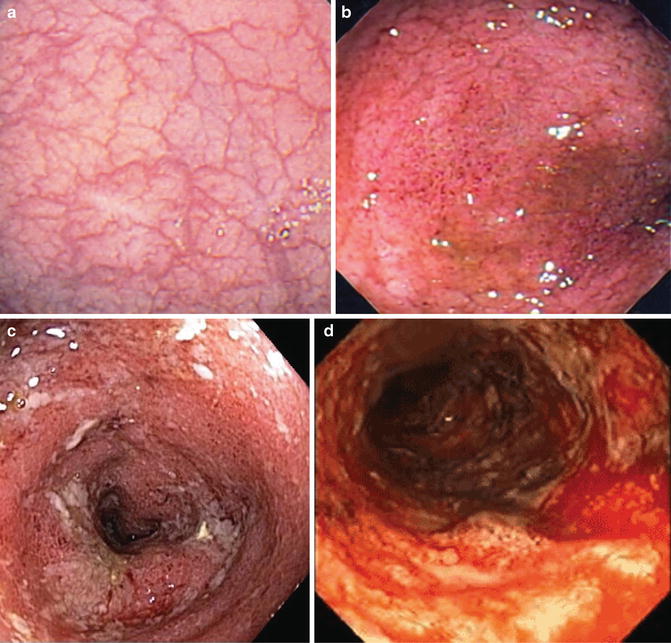

Endoscopic Assessment of Mucosal Healing

Despite the increasing emphasis on MH in IBD research and patient care, there is yet no true validated instrument for measuring MH. Numerous endoscopic scoring systems have been proposed for both CD and UC [1]. There have been at least ten disease activity indices developed for UC including the Baron score, which was the original endoscopic grading instrument for UC and focuses on bleeding severity. The Baron score was followed by the development of several other indices including the Mayo endoscopic subscore, which is more extensive and analyzes erythema, vascular pattern, friability, erosions and ulcerations (Table 12.2, Fig. 12.3a–d).

Table 12.2

Mayo score for UC

Score | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Normal or inactive disease | Mild (erythema,decreased vascular pattern,mild friability | Moderate (marked erythema, absent vascular pattern, friability, erosions) | Severe (spontaneous bleeding, ulceration) |

Fig. 12.3

Representative images of the Mayo endoscopic scoring system for ulcerative colitis: (a) score 0 with no disease, (b) score 1 with mild disease, (c) score 2 with moderate disease, and (d) score 3 with severe disease

The newest developed instrument for UC is the UC endoscopic index of severity (UCEIS) [25]. The UCEIS evaluates three descriptors that the developers concluded were sufficient to measure disease severity: vascular pattern, bleeding, and erosions and ulcers (Table 12.3). The worst segment of the diseased colon is scored for each variable on a ranked 0–2 or 0–3 scale and a sum score from 0 to 8 is then generated. The reliability and validity of the UCEIS were recently published, and it was found that there was satisfactory intraobserver and interobserver reliability as defined by a good overall Kappa (Κ) score of 0.72 for intraobserver agreement and a moderate overall Κ score of 0.50 for interobserver agreement [26]. The authors also reported that the correlation of UCEIS scores and overall assessment of severity was high as defined by a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.93.

Table 12.3

Ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity (UCEIS)

Descriptor (score most severe lesions) | Likert scale anchor points | Definition |

|---|---|---|

Vascular pattern | Normal (1) | Normal vascular pattern with arborisation of capillaries clearly defined, or with blurring or patchy loss of capillary margins |

Patchy obliteration (2) | Patchy obliteration of vascular pattern | |

Obliterated (3) | Complete obliteration of vascular pattern | |

Bleeding | None (1) | No visible blood |

Mucosal (2) | Some spots or streaks of coagulated blood on the surface of the mucosa ahead of the scope, which can be washed away | |

Luminal mild (3) | Some free liquid blood in the lumen | |

Luminal moderate or severe (4) | Frank blood in the lumen ahead of endoscope or visible oozing from mucosa after washing intraluminal blood, or visible oozing from a haemorrhagic mucosa | |

Erosions and ulcers | None (1) | Normal mucosa, no visible erosions or ulcers |

Erosions (2) | Tiny (≤5 mm) defects in the mucosa, of a white or yellow colour with a flat edge | |

Superficial ulcer (3) | Larger (>5 mm) defects in the mucosa, which are discrete fibrin-covered ulcers in comparison with erosions, but remain superficial | |

Deep ulcer (4) | Deeper excavated defects in the mucosa, with a slightly raised edge |

The current gold standard for measuring MH in CD is the CD endoscopic index of severity or CDEIS [27]. The CDEIS involves a complicated and somewhat subjective assessment of the ileum, colon, and rectum in a segmental fashion. A score is generated using the complex formula in Table 12.4. The CDEIS has proven to be too complicated for routine patient care. Consequently, the Simplified Endoscopic Activity Score for Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD) was developed by the CDEIS investigators [28]. The SES-CD scoring system involves four variables: (1) ulcer size, (2) % ulcerated surface, (3) affected surface, and (4) presence of narrowings. Each variable is scored, in segmental fashion from ileum to rectum, on a ranked scale 0–3, and then added together to generate a sum score (Table 12.5).

Table 12.4

Crohn’s Disease Endoscopic Index of Severity (CDEIS)

Variable No. | Variable description | Weighing factor | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

1 | Number of rectocolonic segments (rectum, sigmoid and left colon, transverse colon, right colon, ileum) that deep ulcerations are seen in divided by the number of segments examined | 12 | |

2 | Number of rectocolonic segments (rectum, sigmoid and left colon, transverse colon, right colon, ileum) that superficial ulcerations are seen in divided by the number of segments examined | 6 | |

3 | Segmental surfaces involved by disease. The degree of disease involvement in each segment is determined by examining each segment for the following nine lesions (pseudopolyps, healed ulcerations, frank erythema, frank muscosal swelling, apthoid ulcers, superficial ulcers, deep ulcers, nonulcerated stenosis, ulcerated stenosis) and estimating the number of cm of involvement (one or more lesions present) in a representative 10 cm portion from each segment. The average segmental surface involved by disease is calculated by dividing the sum of each of the individual segmental surfaces involved by disease by the number of segments examined | 1 | |

4 | Segmental surfaces involved by ulcerations. The degree of ulceration in each segment is determined by examining each segment for ulceration (apthoid ulcers, superficial ulcers, deep ulcers, ulcerated stenosis) and estimating the number of cm of intestine involved by ulceration in a representative 10 cm portion from each segment. The average segmental surface involved by ulceration is calculated by dividing the sum of each of the individual segmental surfaces involved by ulceration by the number of segments examined

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|