Fig. 4.1

Three-dimensional endoscopic ultrasonography (3D-EUS). (a) Driving unit. (b) 3D-EUS probe. (c) 3D-EUS system

Fig. 4.2

Principle of 3D-EUS

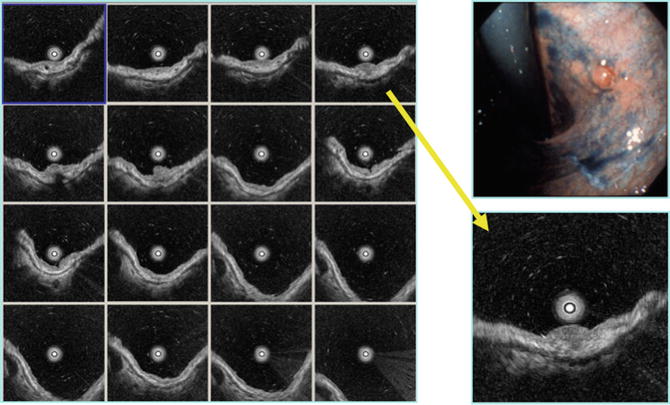

Fig. 4.3

Reviewing function of 3D-EUS 0-IIa, sm (1,250 μm)

Indications of EUS for Gastric Cancer

Local Staging

EUS is the most accurate method for local staging of gastric cancer [13, 19–31]. The clinical utility of EUS depends on whether preoperative assessment of local tumor extent will change the choice of therapeutic procedure. That is, several alternatives are now available for the treatment of both early and advanced gastric cancers. Protocols with curative aims offer two possibilities. The first is a choice between conventional surgical resection or local treatment, such as endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), laparoscopic resection, argon plasma coagulation (APC), or photodynamic therapy. According to the Japanese guidelines for gastric cancer treatment [32], the classical indication of EMR is intramural, well-differentiated adenocarcinoma without ulceration or ulcer scarring, and less than 2 cm in diameter. Furthermore, its indication has been expanded recently as such [33, 34];

1.

intramural, well-differentiated adenocarcinoma without ulceration or ulcer scarring, no size limitation,

2.

intramural, well-differentiated adenocarcinoma with ulceration or ulcer scarring, less than 3 cm in diameter,

3.

sm1 (submucosal invasion less than 500 μm), well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, less than 3 cm in diameter, and

4.

intramural, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, less than 2 cm, without ulceration or scarring.

Those cancers have no likelihood of distant metastasis and can be cured by endoscopic techniques.

The main role of EUS is to choose candidates with those indications. Therefore, we have to differentiate m and sm1 cancers from sm2 (submucosal invasion more than 500 μm).

The second choice is between conventional surgical resection and chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Secondary resection is proposed if there is a significant response with tumor downstaging. If there is no response, treatment is shifted to palliation, which is why it is important to detect whether a T2 or T3 stage tumor is present. Those tumors are curable by surgical resection and, therefore, primary resection is indicated. Tumors of the T4 category without distant metastasis obviously benefit from preoperative chemotherapy. EUS plays a role in this important decision. The overall accuracy of EUS is superior to CT or MRI, although it is still not completely satisfactory.

Wall Structure and How to Diagnose Gastric Cancer Invasion

All along the digestive tract, the normal wall is visualized as a five-layer structure by EUS, with a 7.5–12 MHz transducer (Fig. 4.4) [35, 36]. From the digestive tract lumen inwards, the first hyperechoic and second hypoechoic layers correspond to the mucosa, the third hyperechoic layer to the submucosa, fourth hypoechoic layer to the muscularis propria, and fifth hyperechoic layer to the subserosa and the serosa of the stomach, respectively.

Fig. 4.4

Normal stomach wall by endoscopic ultrasonography

Using high frequency transducers (12–30 MHz), the gastric wall is detected under optimal conditions as a nine-layer structure (Figs. 4.4 and 4.5). In addition to the normal five layers, there is a border echo of the muscularis mucosae, a hypoechoic muscularis mucosae, a hypoechoic inner muscle, a border echo between the inner and outer muscle layers, and a hypoechoic outer muscle [37]. However, the gastric wall is visualized as a seven-layer structure, without components of muscularis mucosae, under usual conditions with high frequency transducers.

Fig. 4.5

Muscularis mucosae detected by EUS (20 MHz)

T-Staging

The TNM system has been generally used all over the world; however, Japanese classification is mainly used in Japan [32]. All endoluminal shapes of gastric cancer can be visualized with EUS, including protruded, flat, depressed, and ulcerated lesions. The tumor mass itself presents as:

T1: Thickening or tumor infiltration of the mucosal and submucosal layer, leaving the fourth proper muscle layer intact. Discrete flat or depressed early gastric cancers are detected as an irregularity of the first layer and a slight thickening of the second layer. However, histological diagnosis should be done by biopsy as a confirmation of T1 lesions.

T2: Infiltration into the proper muscle layer and the subserosa. Detailed pattern analysis is needed to differentiate subserosal invasion from serosal (see below).

T3: Tumor penetration through the serosa (visceral peritoneum) without invasion of adjacent organs or structure.

T4: Tumor invasion to adjacent structures or organs.

In order to diagnose the depth of gastric cancer invasion, it is usually practical to detect the deepest layer that is destroyed by cancer invasion with EUS. However, it is sometimes problematic to diagnose depressed-type gastric cancers with peptic ulcers or fold convergence since peptic ulcer fibrosis is detected as a hypoechoic area similar to cancer invasion (Fig. 4.6). Although in Western countries early gastric cancers are not happened upon frequently, in Asian countries, especially in Japan, 50–70 % of gastric cancers are at early stage. About 20–30 % of early gastric cancers have ulcerative fibrosis (type 0-IIc + III or 0-IIc + ulcer scar). Therefore a method of pattern analysis capable of distinguishing between cancer invasion and ulcer fibrosis has been introduced in order to evaluate depressed-type gastric cancers (Fig. 4.7) [15, 38], and several pattern analyses have been reported [39, 40].

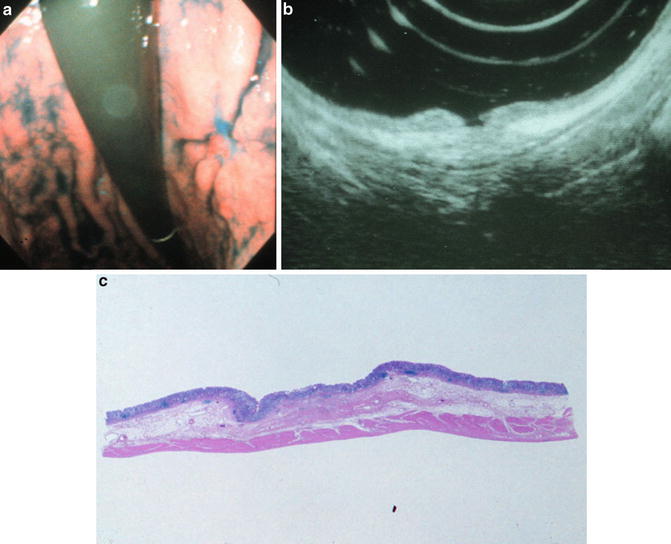

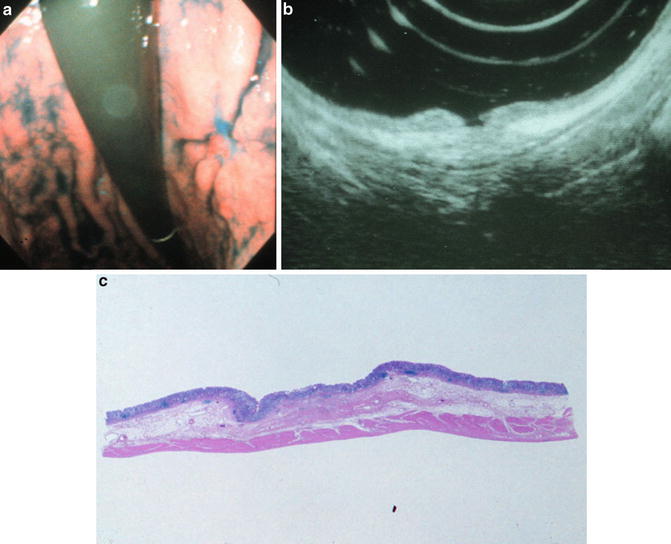

Fig. 4.6

Ulcer fibrosis mimics cancer invasion. 0-IIc + III, mucosal invasion with ulcer fibrosis in the submucosa (a) Endoscopic view. (b) Endoscopic ultrasound image. (c) Histopathological specimen

In order to diagnose the extent of subserosal or serosal invasion, it is first necessary to differentiate between medullary and scirrhous growth, based on their internal pattern (Fig. 4.8). Generally, the medullary pattern has a well-demarcated border and a homogeneous, hypoechoic internal pattern; the scirrhous pattern, on the other hand, has an undefined border, a heterogeneous internal echo, and vestiges of the five-layered structure. In the medullary group, a hump on the outer border means that cancer is still limited to the subserosa, and a serrated outer border indicates serosal invasion. In the scirrhous group, an indistinct hump on the outer border indicates serosal invasion, even if it is small, and only a distinct hump of the outer border indicates subserosal invasion.

Fig. 4.8

How to differentiate between T2 subserosa, T3 serosa, and T4 si with EUS

N-Staging

After scanning of the primary lesion, lymph node metastasis is investigated around the primary lesion, lesser curvature, greater curvature, and celiac trunk. The ultrasonographic features of lymph nodes (homogeneous vs. heterogeneous) is found to be the most sensitive parameter for malignant involvement of nodes, followed by border demarcation (sharp vs. fuzzy), shape (round vs. elliptical), and size (>10 mm vs. <10 mm). If all four parameters are present, the positive predictive value is 100 %, whereas central hyperechogenicity is the typical pattern of benign lymph nodes (Figs. 4.9 and 4.10). However, all four of these features are present in only 25 % of malignant lymph nodes and a single feature can independently predict malignancy [14, 41].

Fig. 4.9

How to differentiate malignant from benign lymph node. Malignant lymph node

Fig. 4.10

How to differentiate malignant from benign lymph node. Benign lymph node

Accuracy of EUS

T-staging

After endoscopic and pathological diagnosis, EUS is the most important diagnostic procedure for patients with gastric cancer. Numerous studies have investigated the accuracy of EUS in TNM staging of gastric cancer. According to a recent meta-analysis, the diagnostic accuracy of EUS for overall T-staging varied between 56.9 and 87.7 % and the pooled accuracy was 75 % (95 % CI: 57–73 %). The pooled accuracy was 77 % (95 % CI: 70–84 %) for T1, 65 % (95 % CI: 71–80 %) for T2, 85 % (95 % CI: 82–88 %) for T3, and 79 % (95 % CI: 68–90 %) for T4 [31]. These vary with respect to instrumentation, scanning frequency, and location difficulty, such as the cardia, pylorus, or an extremely difficult angle. In general, EUS is the most accurate at differentiating between T3 and T4 lesions, which is useful for choosing whether the treatment should be surgery or chemotherapy.

On the other hand, endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection have been accepted as radical treatment for a certain group of early gastrointestinal cancer because of their less invasiveness, cost effectiveness, and associated shorter hospital stay. However, TNM staging is not enough for preoperative evaluation for ESD and EMR. Using EUS, therefore, it is important to differentiate intramucosal cancers from submucosal ones. Numerous studies have also investigated the accuracy of EUS in staging gastric cancer using the Japanese classification system. The diagnostic accuracy of EUS is summarized as follows: mucosal cancer, 86 % (n = 1,391), submucosal cancer, 68 % (n = 744), proper muscle cancer, 65 % (n = 264), subserosal cancer, 80 % (n = 370), serosal cancer, 85 % (n = 227), si (infiltrate to adjacent organ) cancer, 62 % (n = 61), and totally 79 % (n = 3,442) [15, 37, 38, 42–48]. EUS is least accurate for submucosal and proper muscle cancers, similar to T2 lesions. The accuracy of si (T4) diagnosis is not satisfactory because these data are mainly based on surgically resected cases.

Generally, factors that may cause an incorrect diagnosis with EUS are microinvasion, peritumorous inflammation (such as peptic ulcer fibrosis), macroscopic type (such as protruding lesions), and inadequate scanning [15]. Microinvasion may cause understaging, especially if it is very difficult to diagnose sm1 (less than 500 μm vertical invasion to the submucosa) with conventional EUS and an ultrasonic thin probe. If the pattern analysis for depressed-type gastric cancers is not employed, ulcer fibrosis may cause overstaging, according to the depth of ulcer fibrosis [15, 38]. And even if the pattern analysis is employed, it is almost impossible to diagnose between microinvasion such as sm1 and ulcer fibrosis. Protruding lesions introduce an artifact that interrupts the layered structure even if cancer invasion does not exist, and the third layer (sm) commonly protrudes into the lesion. Therefore, it is also difficult to detect narrowing or real interruption due to cancer invasion. Inadequate scanning has been a problem since the earliest days of EUS; that is, it is practically difficult to keep the EUS endoscope in vertical position for relatively small lesions around the cardia, greater curvature of upper body, lesser curvature of angle, and pyloric ring. In fact, there are many factors, such as pulsation, breathing, air bubbles, and mucous, that may cause such an artifact.

In order to perform endoscopic treatment such as EMR and ESD, logically, we have to preoperatively diagnose mucosal and sm1 cancer with high accuracy. There are several reports concerning the pre-procedure evaluation with EUS for ESD and EMR. Kwee et al. did a systematic review of 18 studies, and the sensitivity and specificity of EUS in detecting cancerous extension beyond the mucosa ranged from 18.2 to 100 % (median 87.8 %) and from 34.7 to 100 % (median 80.2 %) [20]. However, we have to differentiate mucosal and sm1 (submucosal invasion less than 500 μm) invasion from sm2 (more invasion) in cases of tumors 3 cm or smaller in diameter, not mucosal from submucosal invasion. Okada et al. reported on this issue and the diagnostic accuracy of EUS in identifying lesions meeting expanded-indication criteria for ESD was 87.8 % (259/295) for differentiated adenocarcinoma 30 mm in diameter or smaller, 43.5 % (10/23) for tumors larger than 30 mm in diameter, and 75 % (42/56) for undifferentiated adenocarcinoma 20 mm in diameter or smaller [21]. Additionally, Mouri et al. concluded the same [22]. As mentioned above, however, conventional EUS has not satisfied the accuracy required for clinical demands. In order to choose candidates for ESD, then, it is feasible to diagnose submucosal invasion more than 500 μm by means of 3D-EUS. According to our data, the diagnostic accuracy of 3D-EUS for diagnosing the depth of gastric cancer invasion is 96 % (n = 325) for mucosal cancer, 74.6 % (n = 181) for submucosal, 72 % (n = 25) for proper muscle, 76 % (n = 25) for subserosal, 67 % (n = 12), 0 % (n = 4) for si (invasion to adjacent organ), and totally 86.3 % (n = 582) (Table 4.1). Basically, 3D-EUS is a kind of ultrasonic probe, therefore 3D-EUS is suitable for evaluating flat and small lesions such as early gastric cancers, but not for advanced gastric cancers because of poor penetration.

Table 4.1

Accuracy of 3D-EUS for diagnosing gastric cancer invasion

m | sm | mp | ss | s | si | ||

T1m (325) | 312

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|