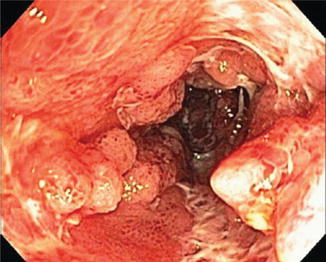

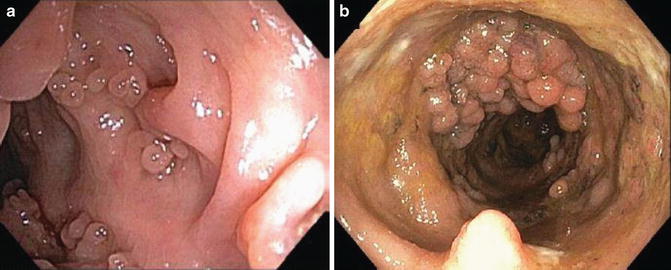

Fig. 6.1

(a, b) Duodenal stricture

Our current understanding of UGI CD has not been systematically evaluated with regards to the true incidence, prevalence, response to therapy or the natural history. The incidence of patients requiring surgical intervention with UGI CD, is also not well defined, likely because surgery of the UGI tract carries significant morbidity relative to surgery on other parts of the GI tract. Nonetheless, it is important to ascertain if patients have UGI involvement to ensure that these patients have adequate control of disease to try and prevent complications and the need for surgical intervention.

Small Bowel Evaluation

Capsule endoscopy (CE) may be beneficial in that the small bowel can be non-invasively visualized with relatively low risk; however, the procedure lacks the ability for biopsy or intervention. In cases when colonoscopy, EGD and small bowel follow-through have been negative, CE findings can be diagnostic. Additionally, CE can assist with evaluating the extent of disease, response to therapy, and detecting recurrence. CE is discussed in more detail in Chap. 7.

Double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) has a limited role since the development of capsule endoscopy. This modality is discussed in more detail in Chap. 8.

Colonoscopy with Ileoscopy

Colonoscopy with ileoscopy is essential in the initial evaluation of suspected IBD in the vast majority of patients. In addition to assessing the severity of disease, endoscopy is also essential to differentiating IBD from other conditions, which may present with similar clinical signs and symptoms. The most common other etiologies include colitis secondary to infectious, ischemic, medication and radiation. Since up to one-third of patients with bloody diarrhea and suspected IBD are found to have an infectious cause, this differentiation is essential [22]. Infectious etiologies tend to present with a yellow or pus-like exudate layered on the mucosal surface; and this endoscopic finding is considered a less common finding in CD or UC [23]. The color of the colonic mucosa has been described as a means to differentiate infection from IBD as infections can produce an intense red-maroon color to the mucosa; IBD patients tend to have a deeper red color, however, this is very subjective and we do not recommend that color be used as routine or primary means for differentiating IBD from infectious etiologies [23]. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and sodium phosphate-based bowel preparation have been reported causing changes in the mucosal appearance that can mimic the appearance of IBD; therefore, these agents should be avoided when possible prior to colonoscopy for the evaluation of suspected IBD [9, 24]. There are no pathognomonic findings of CD on colonoscopy, thus the diagnosis requires thorough history taking, physical examination, serum and stool studies, and biopsy with pathological review is essential.

When IBD is suspected, colonoscopy with ileoscopy should be performed as part of the initial evaluation. An exception to this is in patients with a severe, acute presentation of IBD. Patients with bowel perforation, hemorrhage or toxic megacolon should be immediately considered for surgical intervention and colonoscopy is in general contraindicated [23].

During the initial colonoscopic exam, taking biopsies is essential. Biopsies should target endoscopic abnormalities, but biopsies of normal tissue in the absence of endoscopic lesions should also be taken and include the ileum, colon and rectum. Sampling of normal tissue is particularly important in the identification of skip lesions. An index colonoscopy at the time of diagnosis with documentation of rectal and ileal involvement, distribution of inflammation and severity of disease is critical as future medical therapy will likely produce changes in mucosal presentation (i.e., patchiness) and may hinder the differentiation of UC versus CD.

When performing colonoscopy, the endoscopic appearance of IBD-associated mucosa has limited specificity in differentiating UC from CD. This is particularly true since the endoscopic presentation is variable depending on disease severity and duration. Despite this, inflammation visualized on endoscopy should be characterized regarding both extent of involvement and severity. Involvement of the colonic mucosa may be endoscopically limited to the rectum (i.e., proctitis), left colon (distal to the splenic flexure), extending to the right colon, or diffusely through the colon (i.e., pancolitis) in both UC and CD. Since it may help support a CD diagnosis, it is important to closely evaluate the anal and peri-anal area.

Crohn’s Disease

While the endoscopic appearance of the colon in CD can be identical to UC there are several findings that have been more commonly associated with CD. The endoscopic findings including patchy or segmental colitis, rectal sparing, and involvement of the terminal ileum. Anal or perianal areas are also suggestive of CD rather than UC [9] (see Table 6.1).

Table 6.1

Common findings in IBD patients using EGD, capsule endoscopy, and colonoscopy

Procedure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

EGD | CE | Colonoscopy with ileoscopy | Pathology | |

UC | Normal appearing esophagus, stomach and duodenum | Normal appearing small bowel | Rectal involvement with continuous, proximally advancing inflammation with clear demarcation of normal and abnormal mucosa Mucosal edema and granularity Congestion of vasculature with easy friability and bleeding Pseudopolyps, although not specific May see backwash ileitis for several centimeters | Crypt architecture distortion, sometimes with abscess Decrease in goblet cells Rarely mucin granulomas Basal plasmacytosis Paneth cell metaplasia |

CD | Duodenitis with edema, erythema, thickened duodenal folds Erosions Nodular lesions Friability with bleeding Duodenal stricture Similar findings in stomach including pyloric stricture | Mucosal breaks, although not specific | Inflammation limited to rectum, left colon, right colon, or diffusely through the colon. May also extend to ileum Often patchy or segmental involvement with skip lesions Discrete and/or serpiginous ulcers Cobblestoning +/− aphthous ulcers +/− rectal sparing +/− perianal involvement +/− fistulas | Crypt architecture distortion, sometimes with abscess Non-caseating granulomas Patchy distribution |

Another endoscopic finding more typical of CD patients with mild disease is small aphthous ulcers, which are related to submucosal lymphoid follicle expansion; these punched-out ulcers can coalesce to form a larger ulcer with a star appearance, referred to as stellate ulcers [22]. With increased severity of CD, the submucosa becomes more edematous, which creates a cobblestoned appearance; this suggests a chronic process. In very severe cases, patients may have larger ulcers that are linear (bear claw) (Fig. 6.2) or deep and serpiginous in shape [25]. Both the findings of aphthous ulcers or deep linear or serpiginous ulcers have been more commonly associated with CD. Of note, the colonoscopic findings used to describe UC can all be present in patients with Crohn’s colitis and this can be indistinguishable from typical UC. These findings are described in the following section regarding the colonoscopic appearance of UC.

Fig. 6.2

Linear ulceration in Crohn’s disease

Ulcerative Colitis

What helps distinguish CD from UC is that in the latter, inflammation starts in the rectum with proximal extension in a continuous, circumferential manner without skip patterns. Involvement can end at any location or extend to the entire colon, but the entirety of segment that is involved should have uniform involvement regardless of the extent of disease. By definition, the rectum in a patient with suspected UC should be involved. If there is no microscopic and/or macroscopic evidence of UC on rectal biopsies, UC is ruled out.

Endoscopically, patients with newly developed UC present with a loss of mucosal vascularity. As the disease advances in duration and severity, the appearance progresses to mucosal edema, hyperemia from increased surface blood flow and vasculature congestion with easy friability (Fig. 6.3) and bleeding; the severity of endoscopic inflammation is generally worse in the rectum unless rectally instilled medications have been used. There are often clear boundaries between inflamed and normal mucosa [26]. Persistent edema creates an irregular granular appearance (“wet sandpaper”) [23]. With more severe disease, discrete ulcerations develop and often bleed spontaneously, but unlike in CD, these ulcers are also surrounded by inflamed mucosa and there should be no skip lesions [22, 27, 28] (Fig. 6.4).

Fig. 6.3

Mild UC with friability

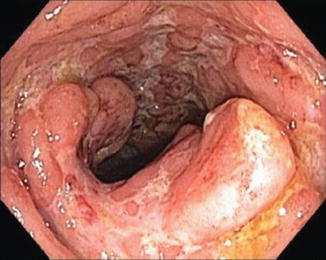

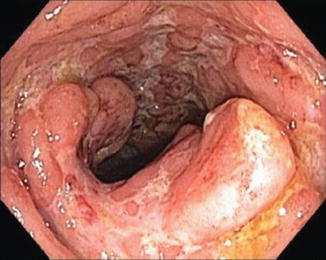

Fig. 6.4

Severe UC

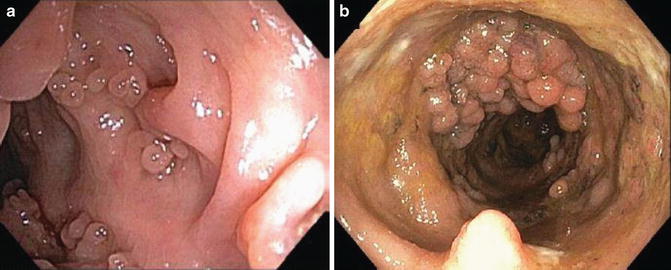

As the disease becomes more chronic, the mucosa begins to atrophy resulting in narrowing of the lumen and a loss of haustral folds [27] (Fig. 6.5). This results from changes in the muscle layer in the setting of chronic inflammation. As ulcers heal and are replaced with scar tissue, residual mucosa protrudes in a nodular fashion forming pseudopolyps (Fig. 6.6a, b). The finding of pseudopolyps is not exclusive to UC, but this finding is less common with other etiologies [26]. Although there is no known malignant potential of pseudopolyps, biopsies should be taken as it is not possible to distinguish pseudopolyps from other polyps on their endoscopic appearance. In particular, targeted biopsies should be obtained when a pseudopolyp is isolated, greater than 1 cm and/or when there is a hemorrhagic surface to rule out dysplasia [26].

Fig. 6.5

Loss of mucosal vascularity and loss of haustral folds

Fig. 6.6

(a, b) Pseudopolyps

One exception regarding rectal sparing in UC patients has been described in patients with UC and primary sclerosing cholangitis [22]. However, this again is not a pathognomonic finding and the entirety of the patient’s disease should be taken into account to distinguish between UC and CD.

Significance of Ileoscopy

In all cases of suspected IBD, intubation of the terminal ileum (TI) with biopsies should be attempted and with the exception of a stricture, should be achievable in the vast majority of patients. With any new IBD diagnosis, it is important to establish the extent and distribution of disease. Involvement of the ileum generally suggests CD (a finding that may result in a change from a prior UC diagnosis). As histology is more sensitive than endoscopy to detect CD, biopsies regardless of the endoscopic appearance of the TI are essential. Ileal involvement (Fig. 6.7) does not simply result in a CD diagnosis, however, since there is a subgroup of patients that have suspected “backwash ileitis,” estimated at about 10 % of patients with pancolonic UC [24, 26]. This is generally described as a patchy, non-ulcerative inflammation of the terminal ileum. CD ileitis is favored if discrete ulcers and/or strictures are present; “backwash ileitis” would not produce ileal stenosis, cobblestoning (Fig. 6.8a, b), or any ileocecal valve abnormalities [8, 24]. While TI involvement in IBD is not considered pathognomonic of CD (Fig. 6.9), the finding of “backwash ileitis” has not been extensively evaluated with regard to the long-term significance and what, if any, effect it may have on the outcome in treatment of IBD patients. We consider the findings that characterize “backwash ileitis” as non-specific and suggest this finding be interpreted with caution, especially if making therapeutic decisions based on this finding.