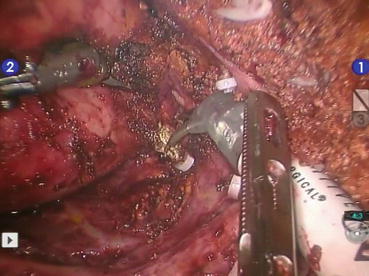

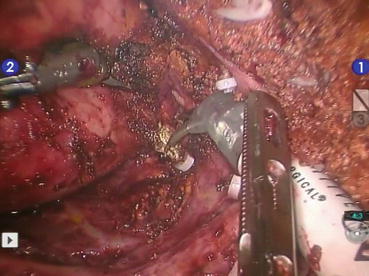

Fig. 20.1

Liver resection using two stay sutures for retraction. One of them is exteriorized (the right one)

20.5 Robotics for Benign Liver Tumors

The da Vinci robotic system can be used for all the spectrum of benign liver conditions. From a technical perspective, the robot can be used for:

Deroofing of nonparasitic liver cysts (NPLC)

Enucleation of benign solid tumors and parasitic and nonparasitic liver cysts

Liver resection for benign tumors

A real advantage of robotics over traditional laparoscopy to carry out such procedures is not clearly demonstrated [3]. Therefore, the authors’ choice is to limit a robotic approach to most complex cases for location, dimensions, and relationship with the main liver vessels.

20.5.1 Deroofing of Nonparasitic Liver Cysts

Deroofing of NPLC consists in the aspiration and cutting out the more external portion of the cystic wall. Laparoscopically this procedure is considered a simple task that can be carried out with electrocautery or the Harmonic ACE (Ethicon Endosurgery, OH, USA). Robotics seems to have nothing more to add. Since aspiration of the cystic fluid is an important step of the procedure, a fourth accessory trocar is required for the robotic procedure in respect to the three trocars required by laparoscopy. We suggest to limit deroofing of NPLC for teaching purposes at the beginning of the surgeon’s learning curve.

20.5.2 Enucleation of Benign Solid Tumors and Parasitic and NPLC

Enucleation is considered a safe parenchyma-preserving option for liver hemangiomas and hydatid cysts.

In 1988, Alper et al. described the technique for hemangioma enucleation by dissecting the fibrous cleavage plane between the capsule of the liver mass and the surrounding liver tissue.

This technique resulted in a lower morbidity rate than liver resection, avoiding unnecessary sacrifice of healthy liver parenchyma and damage to blood vessels and bile ducts.

Later, studies demonstrated that complication rate and blood loss were lower for hemangioma enucleations in respect to liver resections [8].

Therefore, enucleation is the treatment of choice for giant hemangiomas when technically feasible, confining liver resection to large, deeply located lesions and to lesions encasing liver great vessels [9]. A hydatid cyst presents technical challenges very similar to those of liver hemangioma. Enlarging hydatid cyst determines formation of an enclosing fibrous wall around the cyst called “pericyst.” Therefore, the hydatid cyst can be removed along with its pericyst dissecting the surrounding compressed liver parenchyma. This procedure is associated to a low rate of recurrence and is named pericystectomy [10]. Endowristed fine movements of the robot allow bloodless dissection along the compressed parenchyma of both hydatid cyst and hemangioma (Figs. 20.2 and 20.3). Hook cautery and monopolar scissors are equally effective for this purpose. For giant liver hemangiomas and hydatid cysts in close relation with a liver vessel, the Pringle maneuver has a tremendous role to reduce blood loss and to carry out a safe dissection (Figs. 20.4 and 20.5).

Fig. 20.2

Pericystectomy of a large hydatid cyst in segments 6 and 7. Portal branches for segments 6, 7, and 8 are exposed on the cutting surface

Fig. 20.3

Enucleation of a giant hemangioma in segment 8

Fig. 20.4

Hemodynamic effect of inflow control. The hemangioma is completely distended when Pringle maneuver is off

Fig. 20.5

The hemangioma is collapsed during the Pringle maneuver

20.5.3 Liver Resections: Technical Aspects of Segmentectomies and Sub-segmentectomies

For segmentectomies and sub-segmentectomies, patient positioning and trocar placement should be individualized according to the tumor location. Pneumoperitoneum induction with the Veress needle can help to tailor trocar position, limiting the use of an umbilical port to the cases where it is really necessary. Anatomical and nonanatomical liver resections of peripheral (segments 2-3-4b-5-6), superficial lesions are generally feasible and can be done with minimal morbidity and mortality rates. Pedicle clamping is optional or can be applied only in case of bleeding, and liver division can be performed with all the available transection devices. Generally 3–4 trocars disposed at the level of the umbilical line are adequate. For lesions located in the posterolateral sector (upper segment 6, segments 7–8), the patient is rotated on the left flank in order to facilitate liver mobilization and inferior vena cava dissection, when necessary. The camera port and the left-sided trocars should be placed as close as possible to the right costal margin, whereas the right trocar can be inserted in the intercostal space between the 10th and 11th rib along the scapular line. Due to the higher risk of bleeding, intermittent pedicle clamping is advisable when approaching posterosuperior segments. Careful ultrasonographic exploration with demarcation on the Glisson capsule of the right hepatic vein can avoid major bleeding during parenchymal transection. For deeply located lesions or when the tumor is close to a major vessel, even in case of lesions located in the anterior segments, the “corkscrew technique” can be useful. After identification of the lesion by inspection and intraoperative ultrasound, Glisson capsule is marked with electrocautery 1–2 cm away from the tumor margin. According to the location of the tumor, the marked area is anchored by stitches with caution in order to prevent the needle from entering the tumor. Metallic clips hold the suture together, and upward traction is performed, facilitating the transection of the parenchyma and correct identification of vascular and biliary structures. The control of the surgical margin can be verified by intraoperative ultrasonography during parenchymal transection. Generally, small specimens can be extracted by endoscopic bag through any port site; otherwise, enlarging the umbilical port or rarely a Pfannenstiel incision could be necessary. Robot assistance is particularly useful to perform parenchymal-preserving resections especially in the posterosuperior segments and when the tumor is in contact with a portal branch and hepatic vein and when both are close to the tumor mass. In fact, the endo-wristed instruments allow fine movements and complex transection planes reducing the discomfort coming from the use of rigid tools. Principles of patient and trocar positions in conventional laparoscopic surgery are applicable also for the robot-assisted approach. For liver surgery the robot is docked over the patient’s head.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree