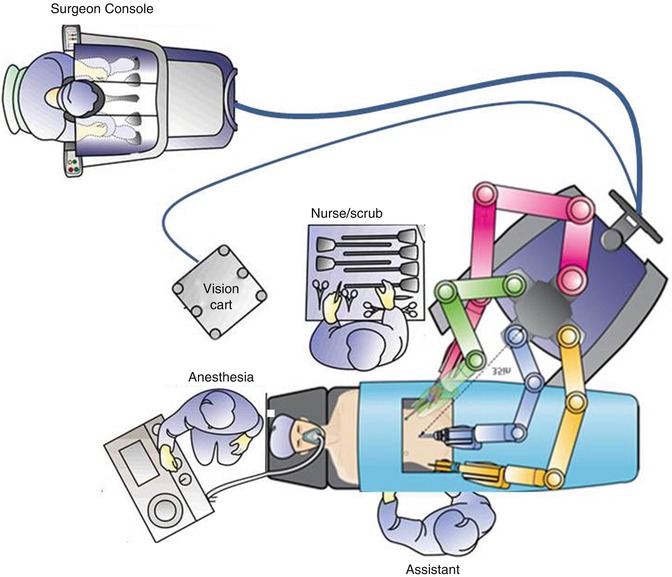

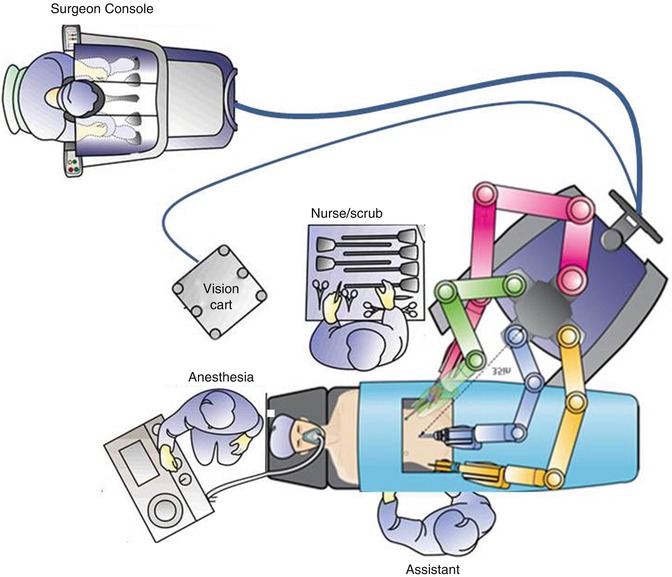

Fig. 17.1

Da Vinci Surgical System (Intuitive Surgical Inc., Sunnyvale, CA). The system consists of the tower, surgeon console, and robotic instrument. The camera arm cradles a 12- or 8-mm three-dimensional 10× high-definition camera with two to three additional robotic arms, which cradle interchangeable, wristed robotic surgical instruments

17.2.1 Large Fibroid Uterus

Large fibroid uteri often pose a laparoscopic challenge, primarily because difficulty navigating around large fibroids limits the surgeon’s ability to dissect and access uterine vasculature and the colpotomy sites with straight instruments. A large uterus also requires more aggressive manipulation and more extensive retroperitoneal dissection because the anatomy is often extremely distorted and accessory vasculature may be present. Robotic assistance adds enhanced vision, which helps with dissection in deep spaces and easier control of bleeding, and the control of the camera, instruments, and uterus with the fourth arm allows for stability and precision in the dissection. In addition, the wristed instruments allow for navigation around bulky fibroids and the uterus, reaching for structures not in the direct line of the port, so that even cases such as that shown in Fig. 17.2 can be successfully accomplished with this approach.

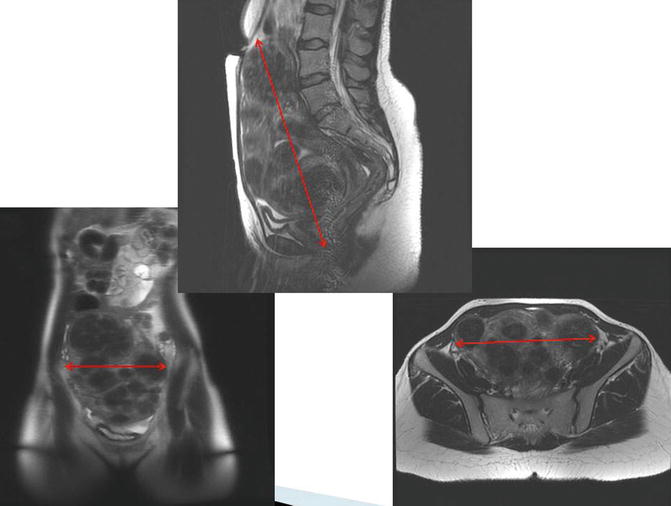

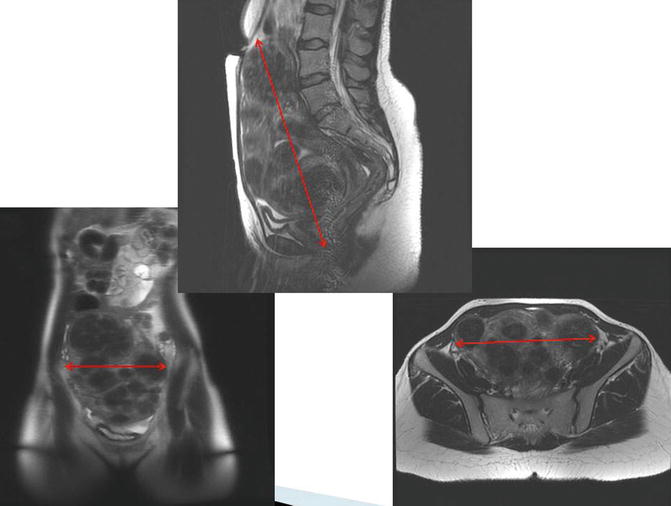

Fig. 17.2

Large fibroid uterus. The enhanced vision and instrument control in robotic-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy increase the likelihood of a successful procedure

17.2.2 Endometriosis

Endometriosis (Fig. 17.3) often causes severe fibrosis and scarring, greatly distorting anatomic landmarks and tissue planes. The enhanced vision and ease of dissection while using robotic instruments can assist in navigating the pelvis, allowing more precise excision of the endometriotic lesions.

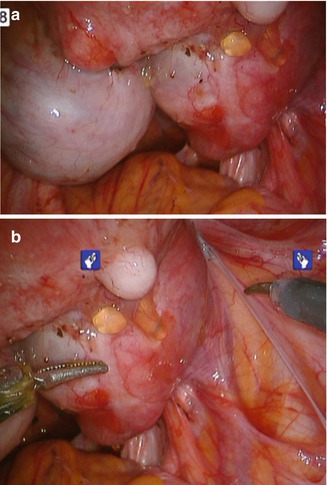

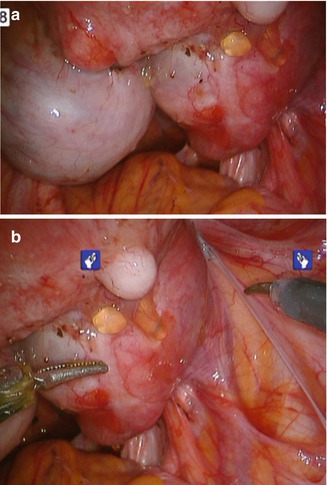

Fig. 17.3

Endometriosis. (a, b) Robotic instruments can more precisely excise these lesions

17.2.3 Obesity

With the increasing epidemic of obesity, Docked robotic instrumentation allows for better control and easier use of instruments despite the thickness of the abdominal wall, which often restricts movement of traditional laparoscopic instruments (Fig. 17.4). In addition, the benefits of laparoscopic surgery greatly decrease laparotomy complications, which are more prevalent in obese patients.

Fig. 17.4

Obesity. Laparoscopic procedures with robotic assistance are more likely to be successful in obese patients, thereby avoiding the need for laparotomy and its complications

17.2.4 Pelvic Adhesive Disease

Extensive adhesions are most commonly associated with previous surgery, especially laparotomy. With cesarean section, as one of the most common surgical procedures performed in women and often performed more than once during the woman’s lifetime, adhesions encountered at time of laparoscopic hysterectomy are a frequent cause for conversion. Similar to its utility for adhesions associated with endometriosis, robotic instrumentation can assist in adhesiolysis for adhesions near the abdominal wall (Fig. 17.5) or more extensive adhesions surrounding the uterus, such as those encountered after previous myomectomy, prior severe pelvic inflammatory disease, or other previous surgeries.

Fig. 17.5

Pelvic adhesive disease. Robotic instrumentation can assist in adhesiolysis for adhesions near the abdominal wall, as shown, or more extensive adhesions surrounding the uterus

17.3 Preoperative Assessment

Appropriate and thorough preoperative assessment is essential for adequate decision-making and surgical planning. A thorough history and physical examination should be performed. Appropriate imaging modalities should be used to confirm the extent of pathology and assess anatomy for surgical planning. The possibility of malignancy needs to be ruled out, so assessment of cervical pathology and endometrial biopsy should be considered. Endometrial sampling is especially recommended if morcellation is likely in patients over age 35, or in those with risk factors such as those listed in Table 17.1, in order to rule out underlying hyperplasia or cancer.

Table 17.1

Risk factors for endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial cancer, or carcoma

Endometrial hyperplasia/endometrial cancer |

Age older than 35 years |

White race |

Nulliparity |

Older age at menopause |

Early menarche |

Obesity |

Family history of ovarian, colon, or uterine cancer |

Use of tamoxifen or unopposed estrogen |

History |

Diabetes mellitus |

Polycystic ovary syndrome |

Gallbladder disease |

Thyroid disease |

Cigarette smoking |

Sarcoma |

Prior pelvic radiation |

Treatment with tamoxifen for breast cancer |

African-American race |

Retinoblastoma (RB1) gene |

If concern about the size or location of fibroids or other pathology remains after a thorough evaluation and imaging, causing doubt about the ability to approach the patient with a robotic approach, an examination under anesthesia or diagnostic laparoscopy at the beginning of the case will help in the decision to proceed with the surgery as planned, versus converting to laparotomy. Table 17.2 illustrates assessment methods used in the preoperative evaluation.

Table 17.2

Preoperative evaluation for candidacy for robotic hysterectomy

Assessment method | Improves candidacy | Decreases candidacy |

|---|---|---|

History | Bulk symptoms, intractable bleeding and pain not responding to medical therapy | Unevaluated postmenopausal bleeding |

For menorrhagia or mild bulk symptoms, alternative management options should be discussed (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and uterine fibroid embolization) | Rapid enlargement of abdominal mass | |

Prior surgical history indicating likelihood of adhesions and need for dissection, or history of endometriosis | Adnexal pathology suspicious for malignancy | |

Physical examination | Assessment of abdominal scars | Multiple abdominal scars (must be assessed to plan access method) |

Access to and mobility of the cervix (at least 1 cm length) | Immobile, fixed uterus | |

Lateral mobility of the uterus | Fibroids filling abdomen, leaving no room for ports | |

Patent vagina with room for manipulator and extraction of uterus | Severe cervix deviation, prolapsing fibroids, cervical mass or fibroid | |

Pathology and laboratory evaluation | Assessment of anemia | Risk factors for sarcoma or suspicious for sarcoma |

Assessment of cervical pathology | Endometrial hyperplasia with large uterus | |

Assessment of endometrial pathology | ||

Imaging (triaxial CT or MRI) | Narrower lower uterine segment | Fibroids filling pelvic cavity |

Well-delineated cervix | Severely deviated or obliterated cervix | |

Lateral side walls and posterior cul-de-sac free of fibroids | Extensive lateral fibroids | |

Examination under anesthesia or diagnostic laparoscopy | Mobility of the uterus from below with the uterine manipulator | Prolapsed fibroids |

Mobility from above with instruments | Cervical fibroids | |

Access to the retroperitoneal space | Lack of mobility of uterus | |

Delineation of the colpotomy site or cervix | Lack of lateral access for retroperitoneal dissection | |

Lack of space for port placement | ||

Suspected malignancy |

Extensive discussion with the patient regarding treatment options and the risks and benefits of each treatment or surgical approach should be undertaken preoperatively, with a thorough explanation of the minimally invasive approach and factors that would cause conversion. Patients with complex pathology are usually willing to undergo an attempt at a minimally invasive procedure, even with a higher risk of conversion, rather than proceeding directly to laparotomy. Adequate preoperative counseling should include a discussion regarding general surgical risks and the risks and benefits specific to laparoscopic or robotic surgery. Risks of visceral injury, including unrecognized injury to bowel or the urinary tract, should also be discussed, and every patient must be counseled in regards to the risk of conversion to laparotomy. Preoperative preparation and the plan for postoperative care should be reviewed. It is important to set expectations for postoperative care and recovery. Many patients have experience with friends or family members who have undergone abdominal hysterectomy with less expedient recovery, so the early ambulation and discharge common after robotic-assisted hysterectomy may be unexpected.

Imaging can assist with assessment and surgical planning. In general, pelvic ultrasound can provide adequate assessment for uteri less than 16 weeks size. However, if fibroids are large or if the uterus is very bulky, the addition of either a triaxial CT scan or pelvic MRI is helpful for surgical planning. These images are especially important for uteri with decreased mobility or lateral fibroids on examination, because the shape of the uterus, the presence or absence of hydronephrosis, and the location of the bladder relative to the uterus are necessary additional information. For example, in the presence of very large fibroids or a low cervical fibroid, a myomectomy may be needed to debulk the uterus first at the time of hysterectomy. The general shape of the uterus, which can be assessed on triaxial CT scans or MRI, indicates the possibility of elevating the uterus out of the pelvis, the location of fibroids relative to the bladder, and the ease of access to uterine vasculature. Thinner lower uterine segments and a longer cervix indicate more accessible uterine vessels, which come in at the junction between the cervix and the uterus. Figure 17.6 illustrates a case amenable to the robotic approach despite a large, bulky, fibroid uterus.

Fig. 17.6

Favorable features for robotic hysterectomy on imaging. In this MRI, the accessibility of the cervix and free pelvic side walls indicate that this case is amenable to the robotic approach despite the large, bulky, fibroid uterus

17.4 Preparation for the Procedure: Setup and Equipment

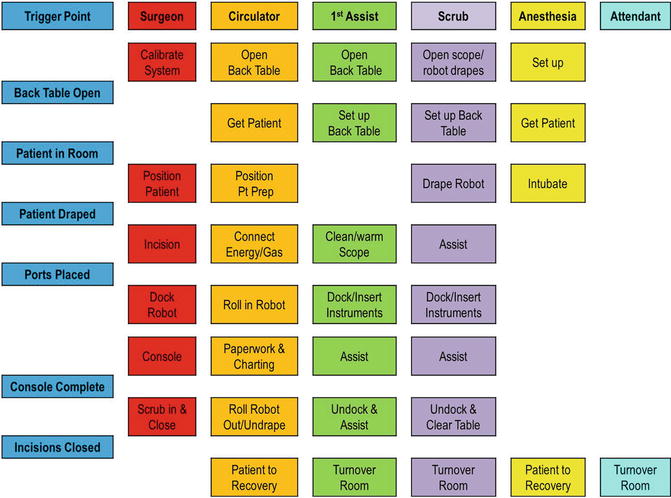

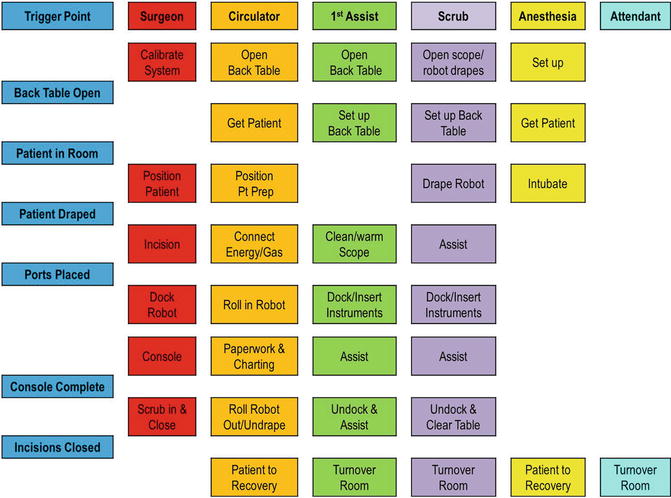

17.4.1 Operating Room Setup and the Operative Team

In the operative suite, a team effort is essential in all surgical procedures, but it is especially critical in robotic-assisted procedures. Involvement of the anesthesia staff, assistants, nurses, and scrub technicians is required in order to provide expedient and efficient care. Protocols that include multitasking and parallel-tasking of all team members allow for increased efficiency and accuracy. As depicted in Fig. 17.7, parallel rather than sequential tasks are assigned to all members of the operating room team, including anesthesia and the surgeon. If possible, a stable and consistent team implementing such a repetitive protocol maximizes efficiency of the surgery and turnover, thus reducing the cost of the procedure. It is also important for all team members and the assistant to have detailed knowledge and practice of quick troubleshooting of the robotic system. They should be trained in the skills laboratory and mock drills and should have checklists that help keep the system working properly and ensure expedient resolution of any problems. The camera and instruments should be checked prior to the start of the procedure so that any problems can be resolved before the patient undergoes anesthesia. While the scrub technician and nursing staff are ensuring the availability and readiness of the equipment, the surgeon and assistant can take care of positioning the patient, while the anesthesia team, often needing two intravenous access sites, places the additional lines. All team members should also pay careful attention to the proper positioning and padding of the patient to prevent injury.

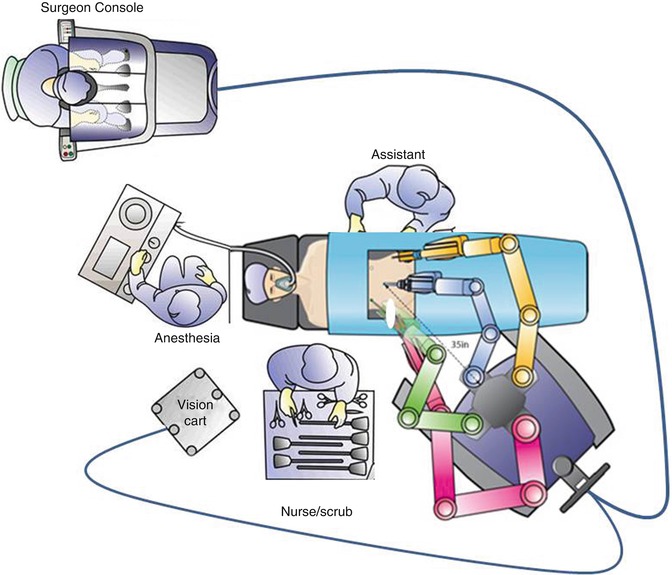

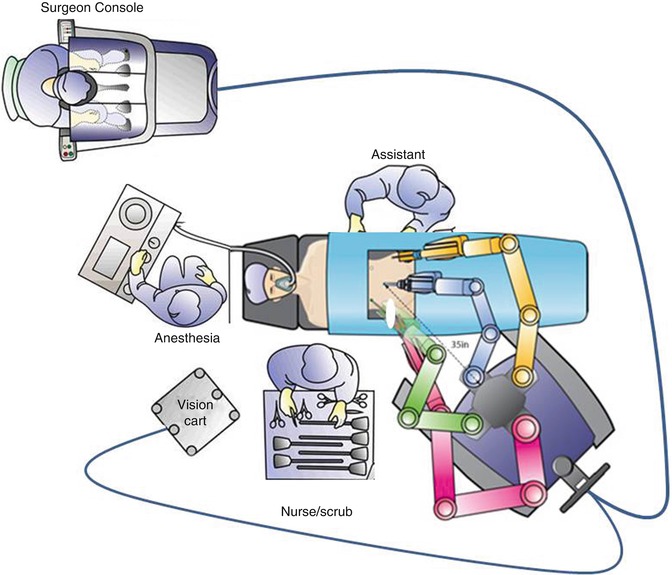

Fig. 17.7

Parallel tasking in the operating room (Modified with permission from Dr. Randy Fagen and Dr. Thomas Payne, Texas Institute for Robotic Surgery, Austin, TX.)

Operating room setup helps to ensure clear communication and the swift execution of needed tasks. By placing the surgeon console near the anesthesia team and scrub technician or assistant, as shown in Fig. 17.8, communication can be improved, as the microphone at the console amplifies the surgeon’s voice. The plan, approach, and necessary instruments should be communicated clearly by the surgeon. Communication with the anesthesia staff regarding expected blood loss, length of surgery, and restriction of fluids should be ongoing. The robot can be docked on either side of the patient, and the assistant should be placed opposite the robot column, in order to give more room to operate. The vision cart and monitors should allow both the assistant and scrub technician to view the screen. The scrub technician should be placed either at the feet of the patient or on the opposite side in order to easily pass instruments or help with instrument exchanges from side to side. Selection of an appropriate bedside assistant and proper placement allowing access to both the uterine manipulator and assistant port is extremely important for an efficient and safe surgical procedure. For difficult cases, the bedside assistant may be one of most important factors determining success, because the surgeon is not scrubbed and is thus not directly available at the patient side, making the surgeon dependent on the skill of the assistant.

Fig. 17.8

Operating room setup. The surgeon console is placed near the anesthesia team and scrub technician or assistant. The robot can be docked on the patient’s left side (a) or the right side (b) (Modified with permission from Dr. Arnold Advincula, Global Robotic Institute, Florida Hospital, Celebration, FL.)

17.4.2 Patient Positioning

As with laparoscopic procedures, patients are positioned in the dorsal lithotomy position, in Trendelenburg with both arms tucked at the sides in anatomic positioning. Padding and proper positioning avoid risk of nerve injuries. As patients are often in a Trendelenburg position (20–30°) for a prolonged period during surgery while the robot is docked, vaginal access must be maintained and it is

extremely important to take measures to prevent the patient from slipping in the caudad direction on the operating room bed. There are a few mechanisms that have been described to prevent sliding in Trendelenburg, including shoulder braces, strapping, egg-crate foam (Fig. 17.9), and bean bag. Each approach has advantages and disadvantages. With shoulder braces, there is concern for brachial plexus injury; straps across the chest can restrict ventilation; the bean bag is quite firm and can cause bruising or neuropathy if not properly placed; gel pads can cause friction burns on heavy patients; while foam must be replaced with each patient and makes moving the patient into position after intubation difficult because of the lack of a draw sheet. Each surgeon must find his or her own comfort level with these measures. Egg crate foam and is the preference of some surgeons, as one study has linked its use to persistent success, with less than 2 in. of slide [15].

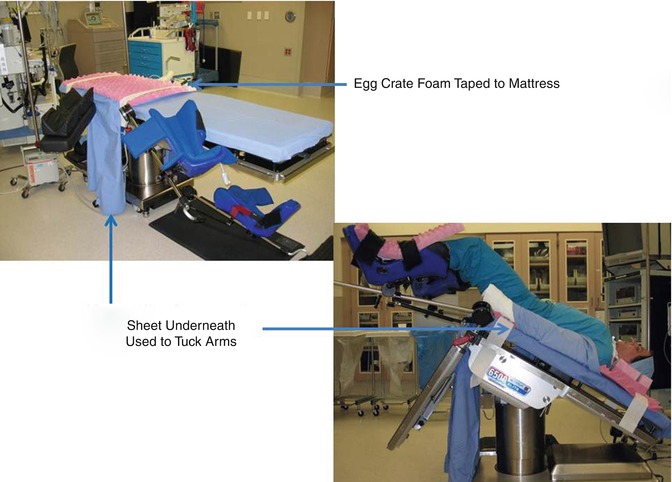

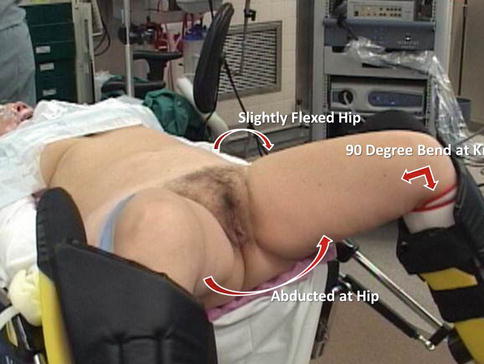

Fig. 17.9

Methods of preventing sliding in Trendelenburg include the use of egg crate foam (Modified with permission from Dr. Arnold Advincula, Global Robotic Institute, Florida Hospital, Celebration, FL.)

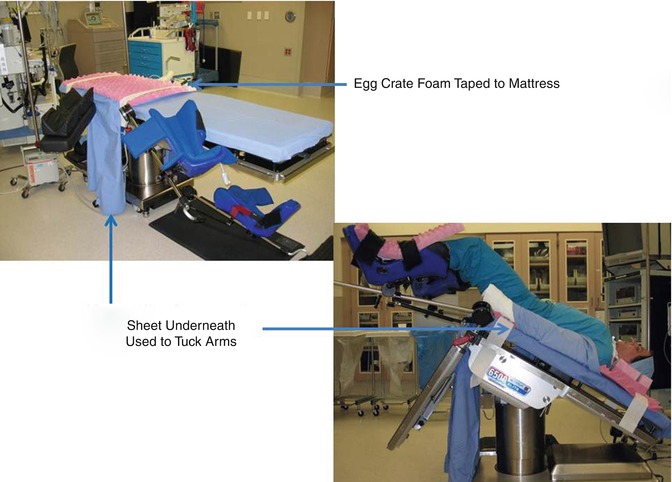

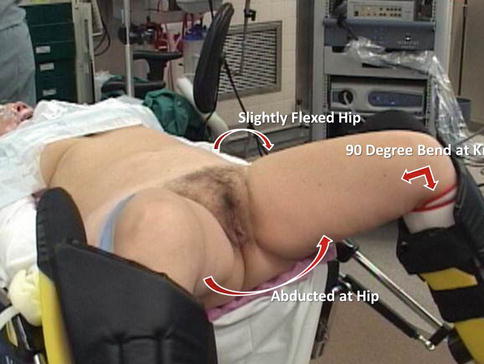

While positioning a patient’s legs in the stirrups, meticulous attention should be given to correct placement and padding and to the angles of the hip, knee, and ankle joints in the stirrups in order to prevent nerve injury (Fig. 17.10). As the stirrups will be dropped for docking, the legs should be positioned with the stirrups already dropped maximally; after positioning, they may be elevated slightly in order to prevent femoral nerve stretch injuries when the legs are moved under the drape.

Fig. 17.10

Leg positioning requires meticulous attention to correct placement and padding and to the angles of the hip, knee, and ankle joints in the stirrups, in order to prevent nerve injury (Modified with permission from Dr. Arnold Advincula, Global Robotic Institute, Florida Hospital, Celebration, FL.)

Similarly, while tucking the arms, attention should be paid to proper padding at the elbows and wrists while watching the position of the thumbs and hands; padding around the hands and wrists will prevent catching them in the stirrups (Fig. 17.11). The team should ensure adequate preparation of surgical sites, including a wide prep on legs, buttocks, and inner thighs, as vaginal access for vaginal morcellation may be needed.

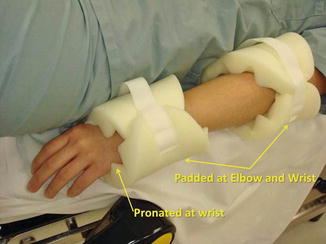

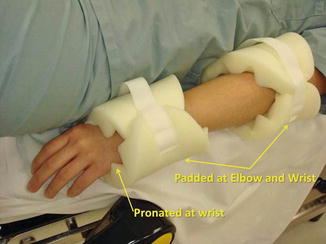

Fig. 17.11

Arm positioning requires attention to proper padding at the elbows and wrists, care with the position of the thumbs and hands, and padding around the hands and wrists to prevent them from catching in the stirrups (Modified with permission from Dr. Arnold Advincula, Global Robotic Institute, Florida Hospital, Celebration, FL.)

17.4.3 Specialized Equipment

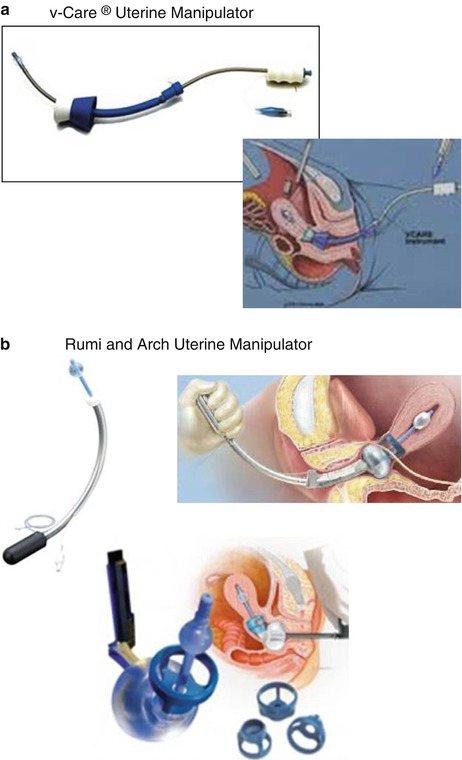

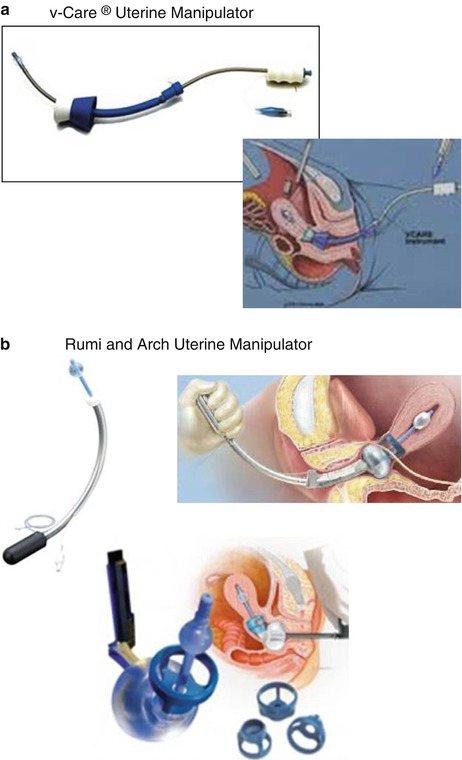

The uterine manipulator has two purposes: (1) to elevate the uterus up and out of the pelvis and thus elevate the uterine vasculature away from the ureters, presenting tissue for dissection, sealing, and cutting; and (2) to delineate the vaginal fornices for colpotomy, or to help identify an appropriate location for supracervical hysterectomy. The colpotomy ring acts additionally as a homing device, allowing delineation of anatomy relative to it in the face of distorted anatomy, bulky fibroids, or extensive adhesions. All uterine manipulators share the ring concept, something to push the uterus upwards, and some manner of colpotomy delineation. Figure 17.12 shows the two most commonly used manipulators.

Fig. 17.12

The two most commonly used uterine manipulators are the (a) VCare (ConMed; Utica, NY) and the (b) KOH Colptomizer System (Cooper Surgical; Trumbull, CT), attached to either the RUMI Advanced Uterine Manipulation System (Cooper Surgical; Trumbull, CT) or the Advincula Arch (Cooper Surgical; Trumbull, CT). (a) The plastic VCare device has an S-shaped curve. The colpotomy ring has the advantage of having a groove for colpotomy, but it is somewhat soft and the ring is not fenestrated, making it a little more difficult to identify the fornix. In addition, as the device is plastic, it can easily bend, making it difficult to push up and manipulate a larger uterus. As it is one piece, it cannot be left in vaginally and may be a bit easier to place. (b) The older RUMI Avanced Uterine Manipulation System (Cooper Surgical; Trumbull, CT) and newer Advincula Arch are made of Metal. The Arch is the same shape as the Aumi or Humi manipulators (both by Cooper Surgical; Trumbull, CT) and have the advantage of not bending or breaking with a large uterus. In addition, its arched configuration helps to push the uterus up and out of the pelvis, providing access to uterine vasculature and colpotomy around large fibroids and making it possible to identify the colpotomy site in a setting of dense endometriosis or adhesions. The firm KOH Colpotomizer™ (Cooper Surgical; Trumbull, CT) attached to the Rumi or Arch has fenestrations and a uniform shape that allows easy identification and palpation of the ring and acts to push ureters more laterally, away from uterine vessels (Images from Cooper Surgical, Trumbull, CT, and ConMed, Utica, NY)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree